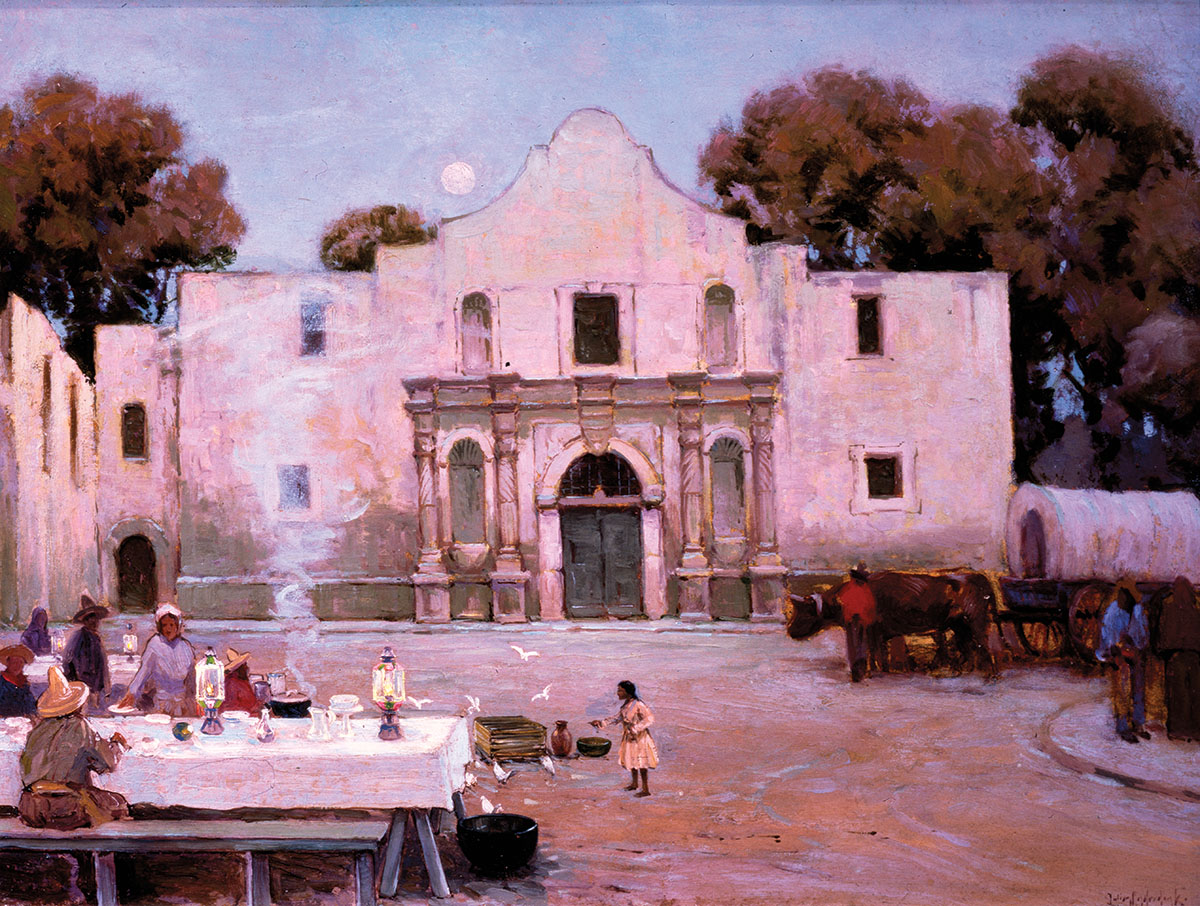

For many Texans, taking photographs of bluebonnets is an annual tradition. But in the early 20th century, Julian Onderdonk was among the first artists to capture these spring blooms with a camera; he then used these black-and-white images as the basis for his finely colored drawings and paintings. Over the span of his career, he created in excess of 1,000 works, and more than 200 were of these iconic lupines. He depicted them in all kinds of conditions: at dawn, midday, and dusk; under azure skies dressed up with puffy white clouds; and even through a scrim of rain. His loose, expressive brushstrokes conveyed the vibrant beauty of the thick-growing flowers, particularly in the areas near his hometown of San Antonio, where they blanketed rolling hills stretching into the hazy distance or popped up in bright spots of color amid the rocky terrain.

Born in 1882 in San Antonio, Onderdonk received artistic training from his father, the painter Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, before traveling to New York at the age of 18 to study at the Art Students League under renowned American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. However, even while living on the East Coast, he maintained his connections to his home state. In 1906, he agreed to procure works to be exhibited at the annual Dallas State Fair (now the State Fair of Texas) and continued to do so for the remainder of his life.

After marrying and starting a family of his own, Onderdonk eventually returned to Texas in late 1909 and applied the artistic lessons he had learned to his native landscape. “San Antonio offers an inexhaustible field for the artist,” he once commented. “Nowhere else is there such a wealth of color. In the spring, when the wildflowers are in bloom, it is riotous: every tint, every hue, every shade is present in the most lavish profusion.” The Texas Legislature declared the bluebonnet the state flower in 1901, and Onderdonk began to make it his focus in the years following his return. The sweeping vistas of indigo hills that he went on to produce in multitude earned him the moniker “the bluebonnet painter.”

Yet Onderdonk portrayed other, less-celebrated flora as well: golden fields of coreopsis, clusters of cacti sporting orange and yellow blossoms, scraggy mesquite trees, and live oaks with twisting limbs and dense canopies. Empty dirt roads sometimes wind through these idyllic scenes, leading the eye to the far horizon. The Guadalupe and Medina rivers figure prominently in several of his canvases, their clear waters flowing past limestone bluffs or pooling quietly along the banks.

Although best known for his impressionistic oil paintings, Onderdonk worked in other mediums too, producing preliminary drawings, pastels, and watercolors in preparation for his larger canvases. These sketches offer insights into his artistic methods, particularly in his close study of plant life.

A number of these studies, as well as his finished paintings, now reside in the Witte Museum in San Antonio, which has the largest collection of Onderdonk holdings in the state—88 works in all, plus some of his sketchbooks, tools, notes, and photographs. In addition, the museum relocated the artist’s much-neglected studio from the backyard of his former home on West French Place to its grounds in 2008. Now open to the public, the diminutive building (measuring about 300 square feet) displays an easel, modeling stand, bookshelves, and painting racks to give visitors a sense of Onderdonk’s working environment.

Bruce M. Shackelford, who serves as Texas history curator at the Witte Museum, consulted on the conservation of the studio. He emphasized the importance of preserving the artist’s legacy: “Julian Onderdonk’s work is important internationally, not just in Texas. He was a brilliant painter who completely understood the light and landscape of the Texas he lived in and depicted it in beautiful illusions of the outdoors.”

Aside from the Witte Museum, the San Antonio Museum of Art and the Villa Finale in San Antonio have a number of Onderdonk’s works in their collections. Examples also can be found across the state: at the Bryan Museum in Galveston; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and the Stark Museum of Art in Orange, to name just a few.

Onderdonk’s paintings drew accolades during his lifetime and after his death at age 40. Ultimately, his work helped launch the now-ubiquitous genre of bluebonnet art, which has inspired legions to document the flowers in various mediums. “Blue wildflowers are not real common,” Shackelford says. “It’s a subject a lot of people pick, but there’s a great difference between those works and Onderdonk’s.”

Many have followed in his footsteps, yet few have matched Onderdonk’s masterful style. Although the flowers he once painted are long gone, his atmospheric landscapes live on, preserving their timeless beauty for generations to come.

The Witte Museum, 3801 Broadway St., San Antonio. 210-357-1900;

wittemuseum.org

Budding Artists

Q&A with botanical illustration instructor Clair Gaston

For more than a decade, Clair Gaston has taught classes in botanical illustration at the Art School at Laguna Gloria in Austin; classes are also held at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin. Gaston offers a few insights for capturing the likeness of plant life.

What advice can you give for beginners?

I recommend taking a class because you get to speak to other people who are starting out, too. You can learn a lot from teachers, but you can also learn a lot from peers. Starting with something simple, like a leaf, twig, or branch, is often much more practical than something like a rose with many petals. I see a lot of beginners who get frustrated because they don’t have the skills to reproduce the fine details of plants, and that just comes with experience. You have to keep going.

What can people gain from observing plant life and flowers?

Observing plants up close connects us to our immediate environment. By looking closely, you notice the miracles that happen when plants grow and bloom and make seeds. You notice the cycles of life. It’s magical. I love the ephemerality of these living things. But as we all know, flowers don’t last. They fade away. When we make a drawing of one, we preserve it. We can hang it on a wall and look at it forever in that one beautiful state.

The Art School at Laguna Gloria,

3809 W. 35th St., Austin. 512-323-6380;

thecontemporaryaustin.org/artschool

Sign up for our new wildflower newsletter

Sign up for our new email series all about the wildflowers of Texas! You will receive 8 emails (about one per week) about Texas' most abundant blooms, where to find them, and how they became so famous.