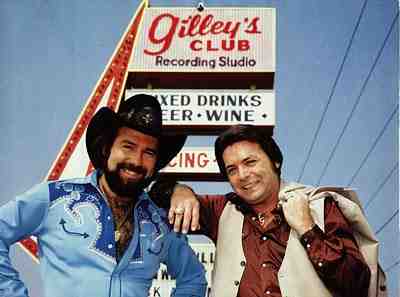

Johnny Lee (left) and Mickey Gilley outside the famous Pasadena honky-tonk. Photo courtesy Third Coast Talent.

The shout-out the 1980 film Urban Cowboy received earlier this month at the Country Music Association Awards show got me thinking about its stars, John Travolta and Debra Winger, and the funky old place that roused an era of garishly feathered hat bands, belt buckles the size of hubcaps, jewelry-studded designer jeans, and $1,000 boots: Gilley’s Nightclub in Pasadena.

Talk about a moment in time. Forty years ago. Dang.

I had experienced Gilley’s on several occasions in the early 1970s before Aaron Latham’s article appeared in Esquire in 1978. Gilley’s was a hardcore honky-tonk that happened to accommodate 6,000, large enough to feature all the popular country road acts. Billed as the world’s largest honky-tonk at the time, the joint wasn’t just big, it was audacious. There was a shooting gallery on premises, punching bags next to the pool tables, pinball machines, arm wrestling, and a rodeo arena that featured a new entertainment contraption called a mechanical bull.

Like most any honky-tonk, it had a rough side that could bring out the worst in some. Fights were part of the show.

The club stayed busy, open from 10 a.m. to 2 a.m., seven days and nights weekly.

Gilley’s opened in 1970 at 4500 Spencer Highway in Pasadena, the blue-collar refinery hub just southeast of Houston. Owner Sherwood Cryer had operated a club called Shelly’s at the location when he entered into a partnership with popular country music singer-pianist Mickey Gilley, a Houston favorite who happened to be cousin to fellow piano-pounder Jerry Lee Lewis.

Gilley’s operated with Mickey Gilley as the featured house act, along with local bands and big-name talents including Ernest Tubb, Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson.

Gilley’s was the perfect meeting place for a bunch of kids in their teens and 20s from small towns and rural parts of Texas and Louisiana who’d come to Houston for work, often in the refineries around Pasadena. If you liked country music—and Houston was the top consumer market of country music then—there wasn’t a better place to be.

Latham, a native of Spur and a regular visitor to Gilley’s, took note and wrote the article “The Ballad of the Urban Cowboy: America’s Search For True Grit.” It was a romantic blue-collar tale about two Gilley’s regulars named Dew Westbrook and Betty Helmer. That article led to a movie deal, a screenplay written by Latham and James Bridges, and the film, much of which was shot on premises. The lead characters, whose names were changed to Bud and Sissy, were played by Travolta—the hottest male lead in Hollywood who was fresh off the films Grease and Saturday Night Fever—and Winger, a moon-eyed tough girl. Club regulars got roles as extras.

The film was a big deal, made tens of millions, and turned Gilley’s into a celebrity hot spot and major tourist destination. Johnny Lee, from Mickey Gilley’s band, had a crossover hit song, “Looking for Love,” on the movie soundtrack. Mickey Gilley had a No. 1 country hit record with his remake of “Stand By Me,” also from the soundtrack. Mechanical bulls became a thing. Practically every other nightspot worth its beer license had to have one. Billy Bob’s opened in Fort Worth’s Stockyards district in 1981 and one-upped Gilley’s as the World’s Largest Honky-Tonk with 100,000 square feet of space and bull-riding on real bulls instead of mechanical ones.

Gilley’s became a beer brand, radio show, recording studio, and logo on shot glasses, jeans, caps, and all kinds of merch. My friend Bob Claypool, the late music writer for the Houston Post, wrote a book about Gilley’s. Gator Conley, the Gilleyrat who worked as a vending machine mechanic and was known as the best dancer and mechanical bull rider at the club, became almost as famous as Travolta for his appearance in the film.

The high lasted for three years or so before the savings and loan scandal centered in Texas erupted and the last significant recession hit Houston. Gilley’s had become less the local hangout and more a rubberneckers’ looky-loo. The regulars moved on.

Mickey Gilley sued Cryer in 1988, charging Cryer failed to maintain the venue and was cheating him out of his share of profits. Mickey got the club and Cryer was ordered to pay $17 million, and eventually declared bankruptcy. The club closed late the next year. The main building burned to the ground several months later in July 1990. Although officials ruled it was arson (with Cryer, a prime suspect, denying any allegations), no one was ever charged. What remained of the structure was demolished in 2005 at the request of the Pasadena Independent School District, which in 1992 bought the land where the club once operated.

Mickey Gilley would find happiness building a theater in the country music tourist mecca of Branson, Missouri. In 1999, Texas Monthly magazine declared Gator Conley as Redneck of the Century.

As for the film, I wasn’t blown away the first time. It’s hard buying into a made-up story when you’ve experienced the real thing firsthand. But after re-watching it, I found Urban Cowboy more enjoyable as a period piece that captures Houston at a real moment, when a peculiar place and the folks who frequented it defined a distinct culture that was neither urban nor rural. Houston’s downtown skyline is impressive in an adolescent kind of way. The Ford trucks, Bud and Sissy’s trailer, the all-night café, the tract home in a new subdivision, and the high-rise penthouse apartment all look genuine enough.

But Gilley’s is the real star. The club looks great with its sea of pool tables, endless bars, massive dancefloor packed with real Gilley’s dancers, low stage filled with Mickey Gilley’s band, the mechanical bull and punching bags drawing their own crowds, and neon signage and red lighting illuminating it all. It’s a quaint sight for COVID times.

John Travolta and Debra Winger are credible blue-collar characters who seem to fall in and out and in love a little too easily. Scott Glenn is suitably menacing as Wes, a rugged fresh-out-of-prison tough guy who steals Sissy’s heart and tries to break Bud’s back while operating the mechanical bull.

While I’ll give bonus points for Wes’ net fabric T-shirt and for the cowboys’ oversized flyaway collars, some details are as hokey as the plot, such as Bud spitting his chaw into a longneck bottom or Wes telling Sissy about living “la vida luna” while doing shots of mezcal. Travolta’s big dance number during “Orange Blossom Special” is more speed clogging or Irish jig than anything remotely country or Western, clearly presaging the popularity of line dancing. But watching the actor two-step with Winger on their first dance, their hands, hips, and feet glued together gliding and skipping as one, makes up for a lot.

In the end, Urban Cowboy—the romanticized vision of Gilley’s—manages to capture a place and time when Houston honky-tonkin’ was the state of the art.