The best trips aren’t always the ones you meticulously plan out months ahead of time. Sometimes, all you need is a burst of inspiration, a full tank of gas, and the open road.

By Michael Corcoran

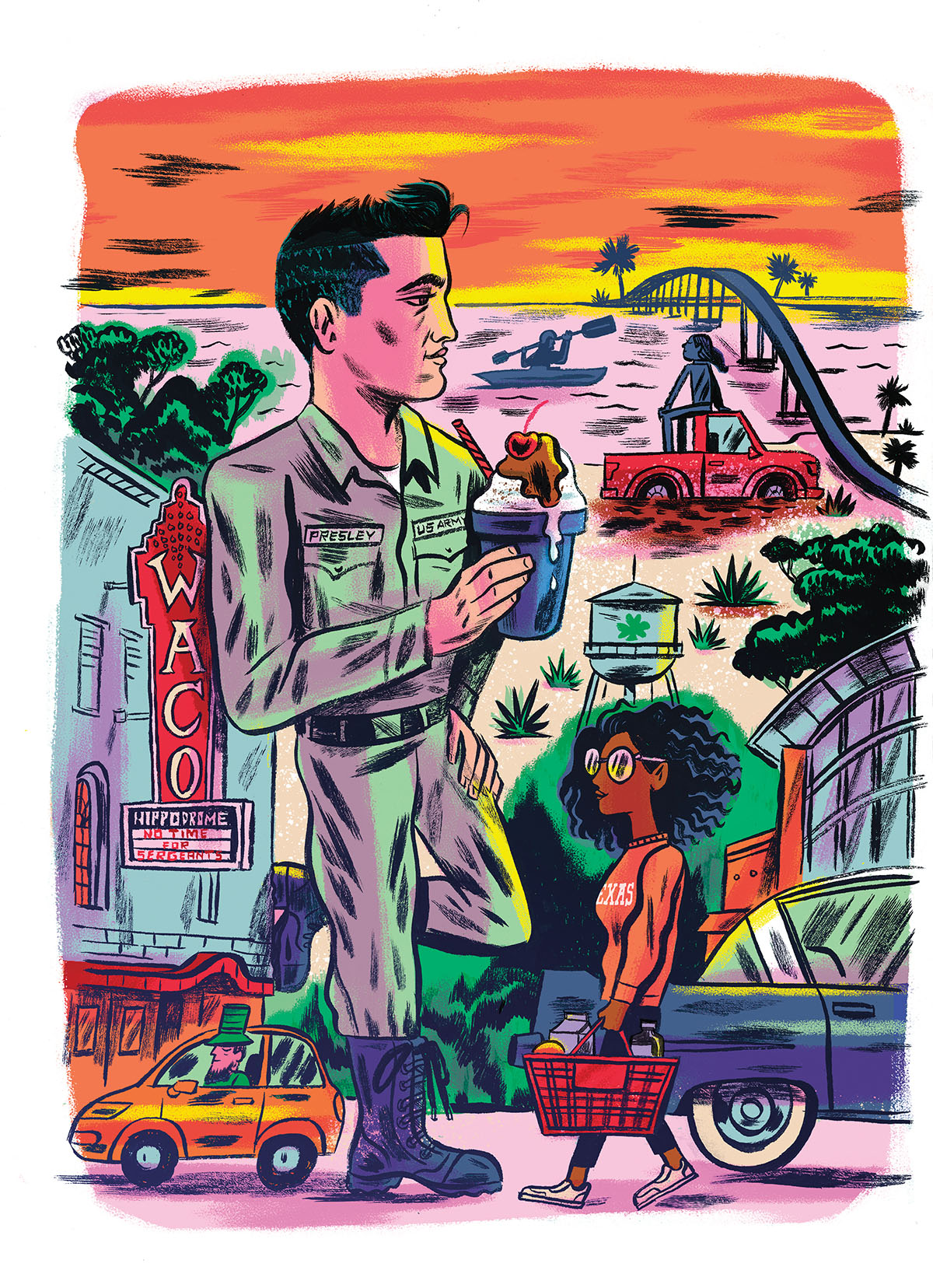

The world’s most famous human showed up for basic training at Fort Hood in March 1958, his squeal-inducing black mane sheared to a flattop. You have to wonder what it was like to be a 23-year-old Elvis Presley, who had been an international sensation for two years before he was doing pushups with a drill instructor barking over him.

With his celebrity, Elvis could’ve dodged the military, or at least fulfilled his service by performing for the troops. He chose the GI life instead, though he would never be an ordinary soldier.

One stir-crazy afternoon last September when I just needed to go for a drive, I decided to put myself in his Army boots. Thoughts about Private Presley rode shotgun, and his music served as the soundtrack to a glorious day spent cruising around Bell and McLennan counties, where Elvis spent six months in ’58 before shipping off to Germany.

I’ve had more exciting road trips and more scenic journeys, especially ones that didn’t involve Interstate 35. But fueled by music, memories, and $1.69 gas, the drive relieved my isolation and provided a necessary reprieve for my pandemic-weary soul.

There’s no wrong time to be born when it comes to being an Elvis Presley fan. I was 2 months old when Elvis released his first No. 1 single, “Heartbreak Hotel,” in January 1956. When I started buying records at age 8, the British Invasion was all the rage, and Elvis was making corny movies and putting out 45s like “Do the Clam.” I was into the Kinks, not “The King.”

I wasn’t fully up on Elvis’ prowess as a singer until my 40s, when I got a box set of his ’60s recordings. I’d always heard Elvis was never the same after the Army—he was discharged in 1960. But the naysayers were wrong. Gospel, rock, pop, country, blues—he could sing anything.

Now a full-blown Elvis fan, I wanted to do more than just listen to his records—and Memphis was too far. So, I drove to Killeen on purpose for the first time and lived that John Hiatt song “Ridin’ with the King.”

There wasn’t much to see, but a whole lot to feel, at the nondescript, rented residence at 605 Oakhill Drive where Elvis saw his mother, Gladys Presley, for the last time before she entered a Memphis hospital. She passed away in August 1958 at age 46, leaving her son an emotional wreck during his last month at Fort Hood.

Elvis was naturally shy, but he loved his fans—at least the ones not hiding in the bushes or chasing him down the street—so he would come out from the house each weeknight at 7 p.m. to sign autographs and talk to the kids clutching his albums. It was a wonderful scene to imagine as I sat parked awhile.

Then, as Elvis did many times over those six months, I made the 60-mile drive to 2807 Lasker St. in Waco. Elvis’ DJ friend Eddie Fadal, who met the singer during one of his barnstorming tours of Texas in 1956, built an addition to his house for Elvis’ weekend escapes. After a recent renovation, it’s available for fans who want to sleep where Elvis slept, booked at theelvishouse.com.

One night, Elvis wanted to go to the movies at Waco Hippodrome to see his friend Nick Adams in No Time for Sergeants. Fadal called the owner to let him know they’d have to sneak Elvis in the back, but word got out and Elvis’ black Cadillac was mobbed outside the theater. He and his entourage would have to settle for milkshakes at Health Camp.

Elvis’ two-year stint of active duty in the Army couldn’t dampen the frenzy of his fans. And he added new ones with his patriotism and desire to be “one of the boys.” Elvis’ cultural significance can’t be overstated. As John Lennon once said, “Before Elvis, there was nothing.”

Most of the country had been in an emotional lockdown before this dynamo popularized sped-up rhythm and blues and expanded the range of popular music. Elvis set young America free with swiveling hips, and my music-fueled trek gave me the same feeling of liberation without ever having to leave the car.

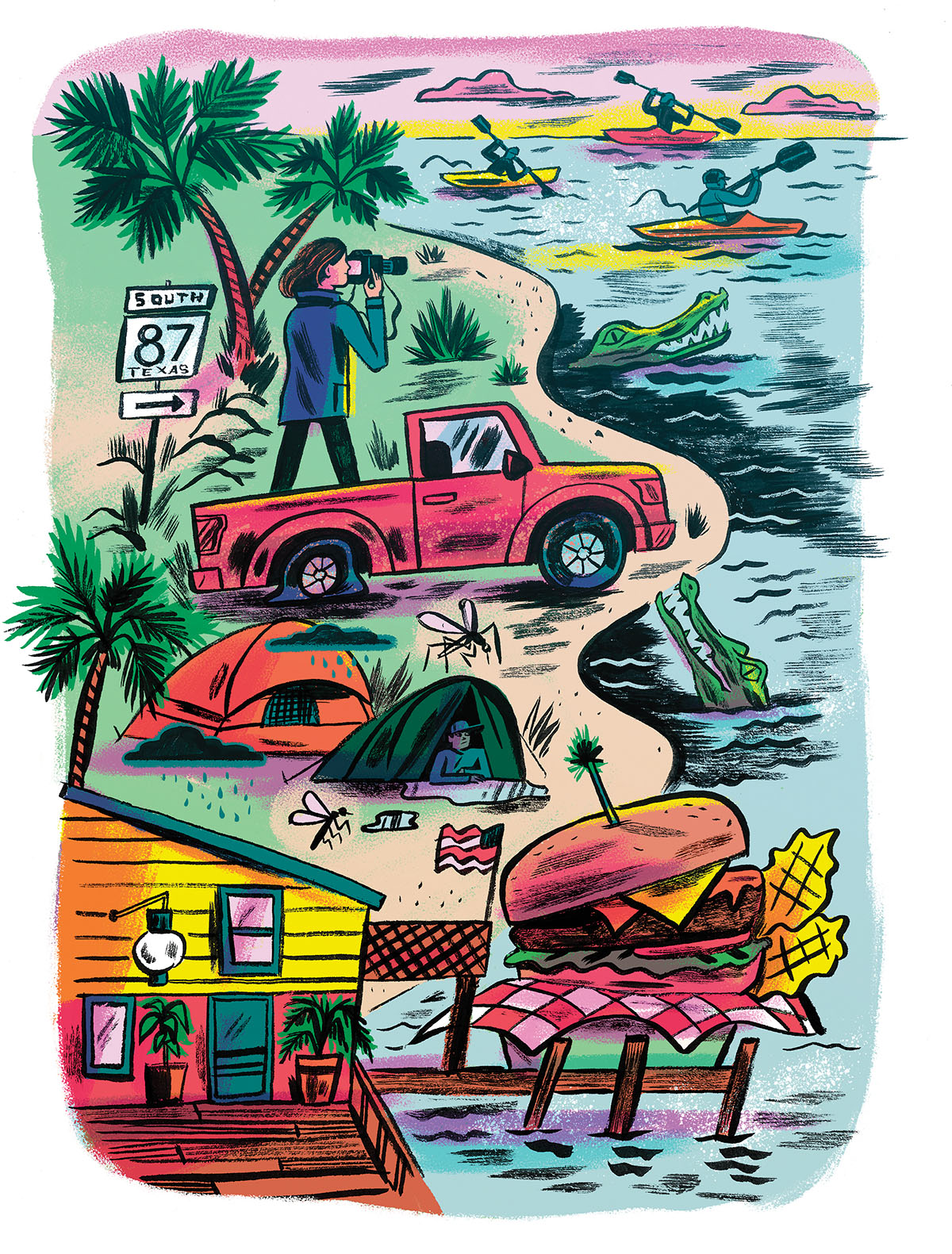

By Pam LeBlanc

Why settle for a mellow, everything-goes-according-to-plan road trip when you can have one splattered in mud, infested with mosquitoes, and laden with metaphorical potholes?

Late last spring, I followed along as a group of five kayakers navigated the Gulf of Mexico and Intracoastal Waterway for a 370-mile trip from South Padre Island to the Sabine Lake Causeway Bridge on the Louisiana border. While the kayakers spent 13 days plowing their way through waves the size of school buses and past the occasional alligator, I motored through my own on-land adventures. Along the way, I discovered friendly little towns and learned a few lessons in self-reliance.

The real fun began halfway through, when in the small seaside community of Sargent, I encountered a construction crew busily replacing the state’s last swing bridge with a permanent span. The construction meant the paddlers would have to portage. While I waited for them to arrive, I met the county constable, who showed me where the team could take out of the Intracoastal Waterway and put their boats back in. As we shuttled around the construction zone, the skies darkened. We needed to set up our tents before a storm hit.

The spot we found seemed perfect: a mostly flat niblet of land next to a barge landing 7 miles north of town. We quickly pitched tents, then headed back to Sargent for a meal as the storm hit. The guys tossed back double cheeseburgers at Hooker’s, but the dirt road had turned to mud by the time we got back to camp. Our tents still stood, but puddles had formed inside mine. Thankfully, I had a cot.

I drifted to sleep but jolted awake a few hours later when a barge parked nearby fired up its generators. The roar continued for the next six hours, along with floodlights so bright they illuminated the entire area. When I staggered out of my tent in the dead of night, the mosquitoes strafed me, and I slipped in the sticky mud. Within the hour, after I’d packed up and was trying to leave, we’d mired my husband’s Ford F-150 in the muck. That’s when I called my new constable friend, who sent someone over to winch me out.

I resumed my road trip, only to discover that my phone, which had gotten wet overnight, had quit working. I followed paper maps roughly 75 miles to Galveston, where a friend invited me over and we placed the device in a bag of rice. That revived the phone, but a kernel got lodged in the charging port, and it took me 45 minutes to whittle it out with a sewing needle. But I was back in business, snapping pictures of the paddling team at the tall ship Elissa and along Bolivar Peninsula.

The biggest challenge still awaited me, though. Two days later, after a couple of relaxing hours at the Stingaree Restaurant in Crystal Beach, I hit the road only to find myself staring at a closure barricade at the end of a remote, two-lane highway. I whipped a U-turn, and moments later my tire pressure gauge lit up. Air gushed from a rear tire as I eased the truck to the side of State Highway 87 and phoned a friend who was 90 minutes away.

My friend promised to help, but determination struck. Surely I could fix the flat myself. Years earlier, my husband had coached me through the process on a much smaller passenger vehicle. I pulled out the owner’s manual, dug out the jack, and assembled the lug wrench. Following the manual’s instructions, I lowered the spare from the truck’s belly, loosened the lug nuts, and raised the truck. I’d wrangled the flat tire from the hub and dragged over the spare by the time my friend showed up.

I waved him away as I used my knees to hoist the spare into position. I replaced the lug nuts, lowered the truck, and turned to take a bow. Hands filthy, bits of asphalt stuck to my skin, and a smile on my face, I declared victory. A couple hours later, the kayakers finished their trip at Walter Umphrey State Park. Strange as it sounds, I couldn’t imagine a better way to cap off my calamitous yet rejuvenating road trip than fixing my own flat.

By Sabrina Leboeuf

For the past four semesters, after long days of classes at the University of Texas at Austin and shifts at our part-time jobs, my roommate, Selam, and I would pack our reusable bags and jump in the car, leaving behind our laptops filled with homework assignments. We blasted Ariana Grande’s Sweetener album to make the most of the short drive, but what we were truly interested in was the destination—our local H-E-B.

As we sung along, the glowing lights of UT’s campus dimmed, and the tower faded from sight. To the right, rows of houses lined the road; to our left, a golf course stood perpetually green. The end of the ride was signaled by three bold letters, glowing red at the corner of Red River and E. 41st Street. That’s how we knew we were in the Hancock neighborhood, seemingly worlds away from the student-filled streets of West Campus.

Selam and I made this trip every other week or so with the excuse of getting groceries, but acquiring daily essentials was only a small part of the equation. On a normal trip, Selam and I would often stay up to three hours in the store just hanging out. We’d spend the bulk of our time walking through every single aisle, catching up while gawking over things we didn’t need, ranging from holiday-themed mugs to frozen black bean burgers. H-E-B was our haven where we could decompress from our hectic lives and reconnect amid shelves of canned soup.

The ritual usually commenced with us enthusiastically deciding whether to share a long cart or handheld basket. We would make several laps around the produce section, venting our frustrations with school and life as we perused the bananas, looking for our preferred level of ripeness. The best shopping trips were hallmarked by picking up boxes of pre-made sushi before checkout.

We vowed never to buy bread because we didn’t want to reduce ourselves to eating sandwiches for every meal, but sliced white and sourdough loaves nonetheless made it into our cart every time. From there, we would invariably find ourselves trapped in the sneakily seductive aisle that combined seasonal kitchenware, discount candy, and pots for plants we didn’t own. Despite being young adults, we are both simultaneously children and old women at heart, equally lured by wine glasses with cheesy sayings and buy-one-get-one-free chocolate bars.

Other mandatory rituals included contracting goose bumps in front of the fridges filled with iced coffee, selecting a variety of dark chocolate, and surveying the frozen vegan “meat.” Sometimes, for no reason other than to delay our return home, we’d walk through the same aisles twice.

We would bag our groceries and checkout-lane impulse purchases in reusable bags, then solemnly pack the trunk and sneak a bite of chocolate. Only then would we turn on the car and head home, picking up Grande’s “breathin” where we’d left off.

Last year, Selam and I weren’t able to take part in our joint trips to H-E-B until August. We spent January through March studying abroad, and once the pandemic hit, Selam went to quarantine in Plano while I went back to Austin.

The fall semester and Selam’s return to Austin brought much joy, but loitering in the aisles of H-E-B wasn’t really an option anymore. Any outing is now accomplished with speed and face masks. At least we still have our car rides there and back, where we can remove our masks, turn up the radio, and enjoy the change in scenery.

By Julia Jones

It began at the Game Xchange in my hometown of Temple. I was browsing the aisles with no money to spare while visiting home from college in 2018 when my friends and I spotted a gem: a 2003 short documentary entitled Growin’ a Beard. The film follows competitive beard-growers preparing for an annual showdown in the Panhandle town of Shamrock, with an original soundtrack of country-style beard-themed songs by defunct Austin band The Gourds. My grandfather’s beard—a cropped salt-and-pepper-but-mostly-salt number he claims he was born with—is legendary among my friends and family, but the beards we saw on the DVD case could rival even his.

Since 1938, the contest has taken place during Shamrock’s St. Patrick’s Day Festival, which was declared the state’s official such celebration by the Texas Legislature in 2013. Entrants must start growing their Donegal—a beard that wraps around the chin, sans mustache—no earlier than Jan. 1. The most authentic Donegal wins the title, a trophy, and cash prize. It’s ridiculous, subjective, and wildly captivating.

After watching the film, my now-husband, Jack, and I threw around the idea of traveling to Shamrock. Neither of us owned anything green or had ever celebrated the holiday before, but we fancied spontaneous day trips across the state. So, at around 1 a.m. on March 17, we decided to take the plunge and set off within the hour.

Six hours of straight driving would land us there two hours early, but detours are nonnegotiable for me. I’d made the drive to the Panhandle in the back seat of my family’s Suburban countless times, but this was my first time taking the reins in my lime green Ford Fiesta. I found myself exhibiting symptoms of middle age almost instantly, stopping to read nearly every historical marker and insisting Jack play various word games with me so I could keep my mind alert in the dark. We made it there at 9:30, with half an hour to spare.

Shamrock was incorporated in 1911 and given its name because it symbolized luck. The St. Patrick’s Day celebration naturally followed a couple decades later. The town, population 1,800, regularly draws thousands for the festival. In 1939, an estimated 30,000 attendees flooded the streets, according to a historical marker downtown.

The year we went, streets were lined with eager revelers overloaded with green. The competitors in that year’s contest numbered only seven, and only six beards were grown in proper Donegal fashion (the outlier didn’t fare well). After approximately three minutes, the winner was declared, the trophy awarded, and the group disbanded.

I would love to tell you that it was far grander than it actually was, that it exceeded my expectations of what a beard-growing competition can and should be, but alas, we were met with simplicity. To me and Jack, however, those moments of sleep-deprived beard-observing joy were all it took to make the trip worthwhile.

In the words of Roy Wardlow, a competitor featured in Growin’ a Beard: “People that grow beards grow ’em because they think they’ve got character.” We had indeed just witnessed character on full display. I realized then a fundamental truth about both my grandfather and the bearded men in front of me: The beard doesn’t make the man; the man makes the beard.

We stayed for the parade that followed and explored the downtown area, festively green and proudly historical. Off Main Street sits a piece of the actual Blarney Stone from Ireland. Legend has it, if you kiss the stone, you’ll become a pro at flattery and wit. We drove west to Amarillo to spend the rest of our sleepless day at the Cadillac Ranch art exhibit, Palo Duro Canyon State Park, and finally, my aunt and uncle’s house in the historic district for a good night’s sleep. The next morning, we headed home—school was starting back up on Monday.