When leading tours of Blue Ostrich, a winery and vineyard near Saint Jo, winemaker Patrick Whitehead likes to share the story of Thomas Volney Munson, a horticulturist from nearby Denison. Though many wine connoisseurs have never heard of Munson, wine historians consider his 19th-century research to be among the biggest influences on the beverage as we know it.

“I like to imagine that Munson rode right through the valley on horseback,” Whitehead says, looking over his leafy vineyards and a sweeping view of the Red River Valley. “I don’t know if he really did, but it’s not out of the realm of possibility. So many of our guests come from the Dallas-Fort Worth area, and they’re always educated people, but they’ve never heard the story. And it happened right here in North Texas.”

In short, Munson helped saved the French wine industry from a vineyard blight in the 1880s by sending Texas grapevines to fortify the Old World vineyards. It’s a story that resonates with contemporary challenges of globalization, disease, and science. It’s also a story with enduring ties to Texas, where the wine industry grows bigger by the year; and to Munson’s hometown of Denison, where Grayson College trains vineyardists and winemakers at its T.V. Munson Viticulture and Enology Center & Memorial Vineyard.

In the mid-19th century, French wine was an international phenomenon and big business, accounting for more than 15% of France’s federal tax revenue. But in 1865, a root louse called phylloxera began wiping out the country’s vineyards. Desperate for a solution, the French reached out to American botanists, including Munson, who was known for his pioneering documentation of native grapevines in Texas and the Southwest.

Munson found and sent specific disease-resistant grapevine cuttings to France, where farmers grafted their grapevines to the Texas roots—literally binding the two together—and crossed them with local plants. The tactics stemmed the tide of phylloxera and saved a range of delicate French grape varieties, including cabernet, merlot, pinot noir, and chardonnay. Even now, 135 years later, France grows wine grapes rooted on the descendants of Texas native plants.

“In Europe they know more about Munson than people over here do, but their livelihood was dependent on those vines,” says Roy Renfro, the retired founding director of the T.V. Munson Center and co-author of the biography Grape Man of Texas: Thomas Volney Munson and the Origins of American Viticulture. “Even the young people today still know about him. They have carried on the story, and when their parents and grandparents take them into the vineyards, they show them the vines.”

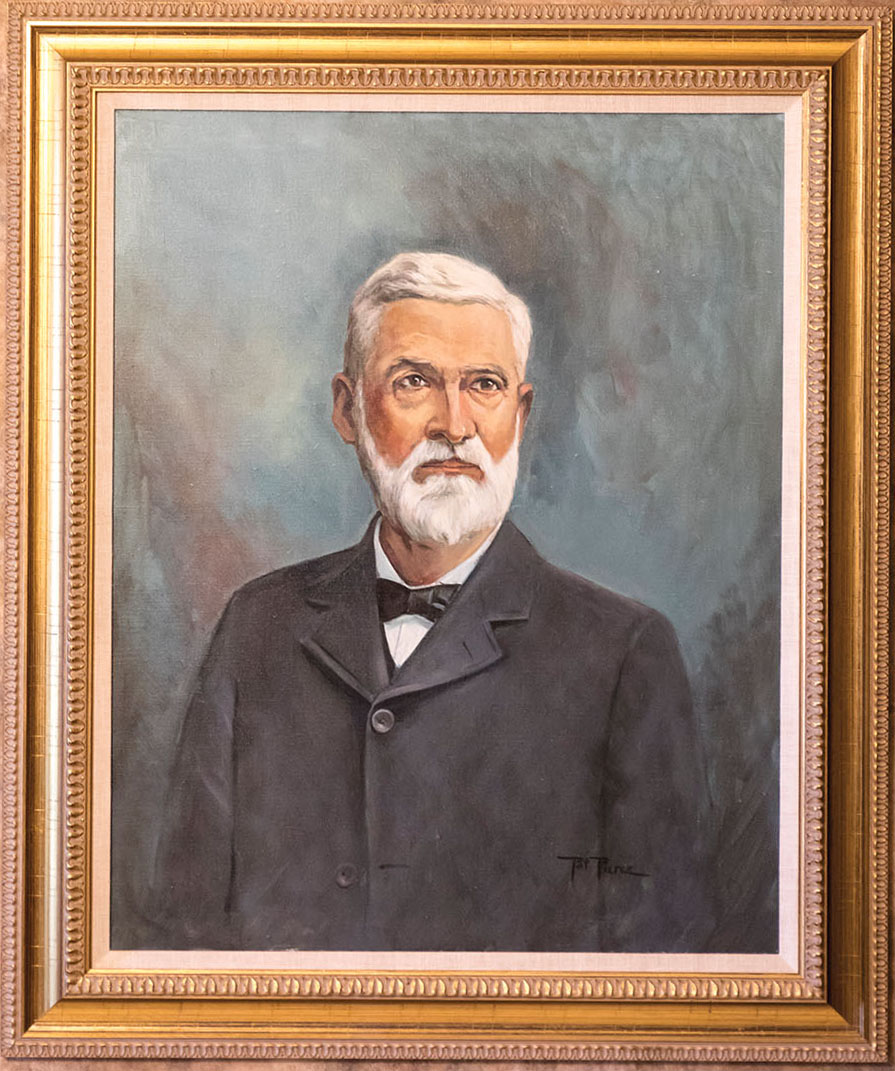

Born in Illinois in 1843, Munson grew up on a farm and attended college in Kentucky, where he became interested in the idea of improving grapes. As Munson wrote in his 1909 book, Foundations of American Grape Culture, he began his life’s work of experimenting with grape hybrids “so as eventually to supply every use and every season with this most beautiful, most wholesome and nutritious, most certain and profitable fruit.”

A Munson portrait

Munson and his wife, Nellie Bell Munson, moved their young family to Denison in 1876 at the urging of Munson’s brother. W.B. Munson was a lawyer and land speculator who helped establish Denison with the arrival of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad in 1872. He trumpeted the region’s agricultural potential, and when T.V. arrived, he discovered eight wild grape varieties growing on the Red River’s banks and bottoms. “I had found my grape paradise!” he later wrote.

Munson opened a commercial nursery, and each fall he would set out across the country in an effort to document every species of wild grape he could find. He scoured Texas, Indian Territory, Mexico, and nearly every state, collecting cuttings and sending them back to Denison by train. By his own estimate, he traveled some 75,000 miles on these expeditions.

“One of the things that I was struck by most in researching him was his absolute dedication to what he was doing,” says Sherrie McLeRoy, an Aledo-based historian and writer who co-authored Grape Man of Texas. “Fortunately he had a very understanding family who weren’t bent out of shape every time he disappeared into the woods or across the country hunting for more grapes.”

Munson’s fame grew in the field of horticulture as did his business, Denison Nursery, which expanded into one of the largest in the South. The nursery shipped to customers across the country—everything from fruit trees to Munson’s patented “diamond scuffler hoe.”

By that time, the phylloxera blight had brought European grape growers to their knees. The pest would eventually destroy two-thirds of the continent’s vineyards, including the majority in France, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. Remedies such as pesticides and field floods proved ineffective or impractical. Initial efforts to introduce American rootstock had failed because the new varieties withered in French soil. That added to skepticism among the Europeans, who were already wary because, decades earlier, American imports had introduced phylloxera in the first place.

Nevertheless, desperation drove the French to turn to the United States, where native grapes evolved to tolerate phylloxera. When a French delegation visited Munson in Denison, the Texas grape expert identified a few species of grapes found in Central Texas, especially the Bell County area around present-day Fort Hood, where the limey soil is similar to that of southern France. The Frenchmen who visited Munson covered 10,000 miles in their research trip across the country, collecting vines along the way. But ultimately it was the cuttings from the scrubby limestone hills of Texas that turned the tide of the vineyard blight.

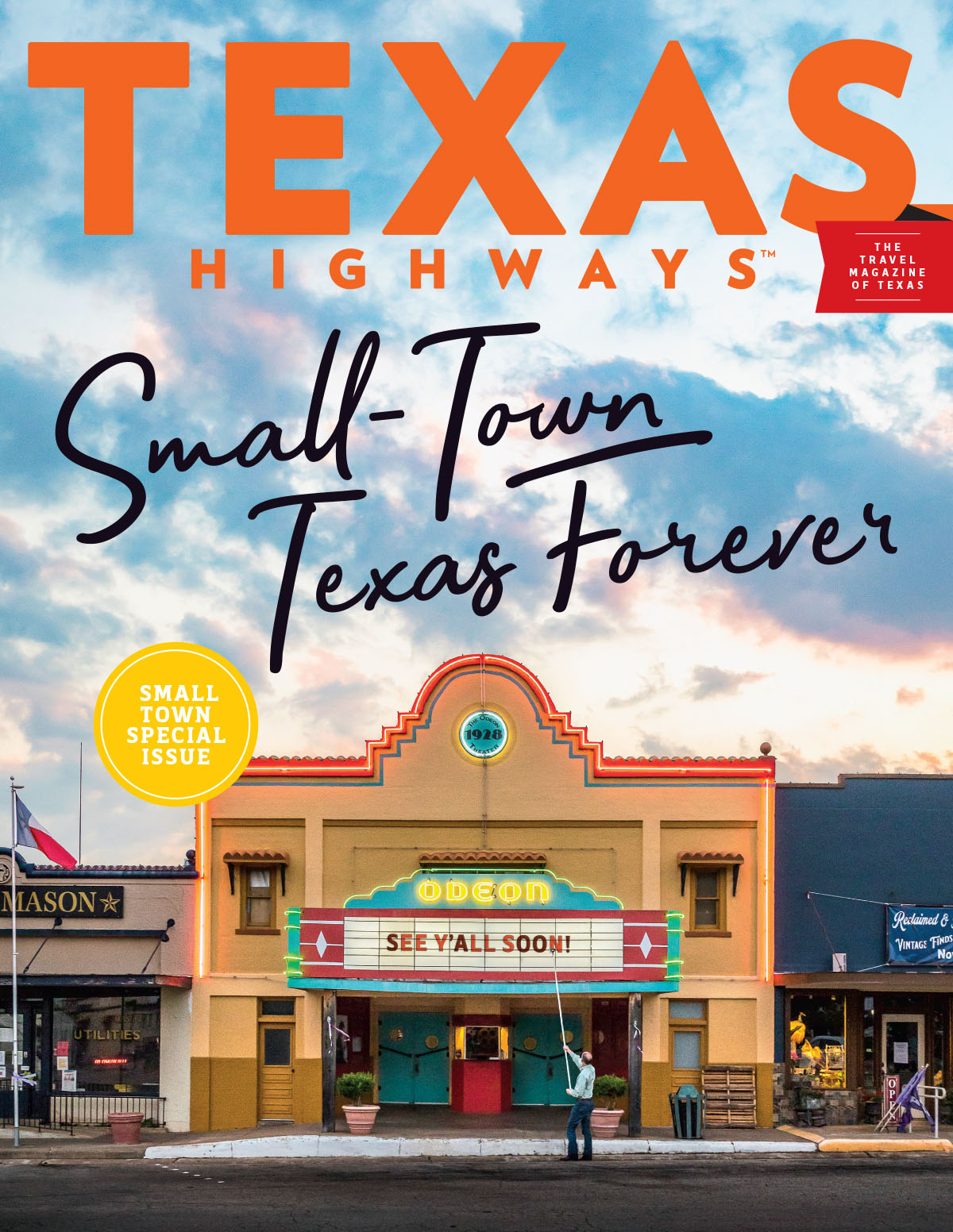

Subscribe to Texas Highways

Subscribers get stories like this before they are available online.

Subscribe today!While Munson’s renown has faded with time, his legacy remains front and center in Denison. Through the efforts of Renfro and the W.B. Munson Foundation, Munson’s 1887 home, dubbed “Vinita,” has been restored. Munson lived with his wife and seven children in the 10-room Victorian Italianate home until his death in 1913. Visitors can see the cellar where Munson made his own wine and kept preserved foods, as well as the second-floor windows opening to a roof where the family slept on unbearably hot nights.

The teaching lab at Grayson College’s Munson Center.

At Grayson College’s West Extension campus, the Munson Memorial Vineyard preserves 65 of the 300 grape varieties Munson developed. (The other 235 have been lost to history.) The vineyard gets about 100 calls a year from grape growers across the country who request cuttings to grow their own Munson vines.

Just up the hill from the vineyard, the college’s Viticulture and Enology Program instructs students in growing grapes (viticulture), making wine (enology), and distilling. Munson photographs and awards adorn the walls, including a replica of the French Legion of Honor medal that was presented to Munson in 1888.

Whitehead, at Blue Ostrich, is among the many Texas winemakers who have attended Grayson College’s program over the years. He notes that Munson’s work informs the science that goes into planting a vineyard and choosing the best rootstock for the local conditions. Like most Texas wineries, Blue Ostrich grows Old World grapevines that have been grafted to rootstocks native to this country.

“Munson thought there was something special about the grapes here in Texas, and low and behold, we are growing Old World grapes very successfully here in Texas,” Whitehead reflects. “If you think about it, we sent that Texas rootstock over to Europe to help with their grapes, and now we have their grapes growing here in Texas.”

Grape Times

5611 FM 2382 in Saint Jo, opens its tasting room and pavilion Thu-Sun. Call first: At press time, reservations were recommended as the winery reopened from the pandemic shutdown. Blue Ostrich welcomes the public to help handpick grapes during the annual harvest, held in late August or early September, depending on conditions.

940-995-3100; blueostrich.net

9356 Grayson Drive in Denison, offers tours by appointment.

903-415-2653; grayson.edu/pathways/viticulture-and-enology

530 W. Hanna St. in Denison, offers tours upon request. 903-463-8621