(Illustration by Michael Witte)

![]() Like the best relationships, it’s an affection that developed over time, rooted in many discoveries. That the region is difficult to get to know is key to the magic: The vast array of mushrooms that hide in the Big Thicket, visible only if you are willing to slow down your pace. The swishy soft soil of Piney Woods trails that reminds visitors you are never really on firm ground when drawing sweeping conclusions about the region’s natural attractions or history.

Like the best relationships, it’s an affection that developed over time, rooted in many discoveries. That the region is difficult to get to know is key to the magic: The vast array of mushrooms that hide in the Big Thicket, visible only if you are willing to slow down your pace. The swishy soft soil of Piney Woods trails that reminds visitors you are never really on firm ground when drawing sweeping conclusions about the region’s natural attractions or history.

My parents made at least one camping trip a year to Lone Star Lake or Lake O’ the Pines. When I broadened my explorations as an adult, I was astonished that my father—an avid outdoorsman and fisherman—never took us to Caddo Lake. I’ll never know whether it wasn’t on his radar or if he just didn’t want to share it. I’d understand if it was the latter. There’s something so mysterious about Caddo, so otherworldly, that you don’t easily invite others into your relationship.

Once asked to write about its history, I decided to interview some of the fishermen I found near its shores. Five hungry men hunkered still as stumps around a tiny fishing camp grocer’s counter. They were settled in, obviously locals. An unexpected man, his jumpsuit rasping new, strode in and disrupted an almost meditative quiet. “I just drove up from Houston to see the lake,” he said, looking confused. “Now…how do I do that?”

“Well,” the grocer answered, “just how much of it did you want to see?”

The cramped crowd laughed. It was an inside joke. Caddo Lake laps the state park boat dock within yards of where the fellows waited to reel in cheeseburgers, but you can’t hear, see, or smell it from there. For all practical purposes until you are in boat-launching distance the lake remains invisible.

That’s the thing about Caddo, for all its nearly 30,000-acres, however you approach it, the how-do-you-get-there-from-here question looms large. The appeal of the lake is as much about its inaccessibility—free public access is limited to one ramp—as it is about the mysteries in its history. As elusive as Eldorado, it’s no drive-your-Chevy-to-the-levy lake serviced by scenic overlooks and paved parking.

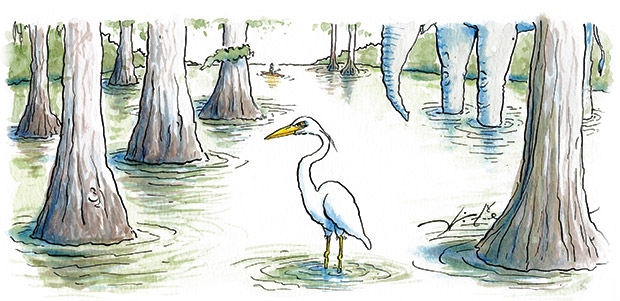

Go visit and you know at once you can never possess Caddo, the way regular visitors feel ownership of, say, Possum Kingdom. Few can claim to know it the way fishermen and boaters predictably chart a day on Lakes Livingston or Whitney. Shallow depths, labyrinthine boat roads, moldering duck blinds, falling timber, and flora that blooms, sprawls, and climbs at preternatural rates means the lake you see today is not necessarily the lake you get tomorrow. To characterize Caddo is like describing an elephant viewed through small holes in a fence—with the mammoth leaning on the fence. Wide views are hard to come by; the broadest expanses are seen from the lake. Otherwise you are limited to peep shows through the humpy knees and elbows of cypress, nets of Spanish moss, and reflections in amber waters. Observation requires a keen sense of what is beyond the slivered sightlines. Your ears are witness to a slosh that might be a gator or the collapse of a card stack of turtles. A misty early-morning scene wafts into memory as you watch a slant of light intensify and burn off the fog. The harder one strives to get an accurate impression of the lake, the more one realizes that like a David Hockney painting the big picture is in fact thousands of tiny snapshots.

Separating myth from reality is equally difficult. Though consistently labeled the only natural lake in Texas, it’s not. Unlike most Texas lakes it is a lake with a past, one shaded by tall tales and time. Where and when did it begin? As with all creation theories there is no consensus. Some say that in the beginning there were earthquakes. Others tell of a Great Flood borne of a Great Raft leading to a Big Bang—of sorts. Others claim it all began with the Fairy. Fairy Lake. On its glistening footprint, hundreds of years before quakes or raft, Caddo may have been born when the Fairy and Sodo Lakes flooded (now less romantically known as the Ferry and Soda Lakes).

The unknowable is central to the ongoing attraction of the maze of bayous, bogs, sloughs, and backwaters sprawling along the border between Harrison and Marion counties in Texas and Caddo Parish in Louisiana. That’s fine with me. I get my Dad’s reluctance to share, too. As Jane Austen wrote in Emma, “If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more.”