We don’t want to accidentally launch anything, so don’t touch any buttons,” says David Cisco, a former spacecraft technician who worked on Project Apollo in the 1960s, as we stand before an array of control panels in NASA’s historic Mission Control. The fact that Cisco is joking—the dials and monitors no longer function—doesn’t diminish the awe that seizes my tour group as we study the rows of beige desks and banks of old-fashioned computer screens.

See NASA’s video montage of that moment on July 20, 1969.

Space Center Houston is at 1601 NASA Pkwy. Level 9 Tours take place weekdays at 11:45 a.m. with additional tours offered at 10:45 a.m. on Mondays and Fridays. Tickets cost $99 and include a discounted 2-day admission to Space Center Houston, and an exclusive behind-the-scenes one-day VIP tour of NASA withi lunch at Johnson Space Center. The tour, which lasts approximately 5 hours, is limited to 12 guests per day, so advance reservations are recommended. Participants must be at least 14 years old. Order tickets online or call 281/283-4755.

This was the nerve center for NASA moon landings in the 1960s and early ’70s, which made household names of astronauts like Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

Cisco, a docent at Space Center Houston—the nonprofit visitor center of NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center—has dropped in on our “behind the scenes” Level 9 Tour. Our guide, Gabe Rangel, is happy to share the spotlight with Cisco. “You don’t have to be the quarterback to be on the team,” says Cisco, recounting his memories of NASA’s early days and the immense group effort that fueled Project Apollo in the heady days of the Space Race.

For the general public, the Level 9 Tour is the only way to get such an intimate view of the space program and its development from the first moonshot through today. Limited to 12 participants per group, the four- to five-hour tour travels by van and makes about eight stops across the 1,600-acre campus. The tour includes sites not normally open to tourists and offers a perspective of the space program several degrees more detailed than the Space Center’s tram ride. As our tour visited Rocket Park, training facilities, and even the NASA café for lunch, the knowledgeable guides provided thorough lectures on past, present, and future missions. We saw posters showing space mission timelines, examples of the suits worn by astronauts across the last half-century, and all manner of patches and paraphernalia from moon stones to newspaper clippings revisiting many of NASA’s proudest achievements. It was as in-depth a trip as any earthbound space cadet could imagine.

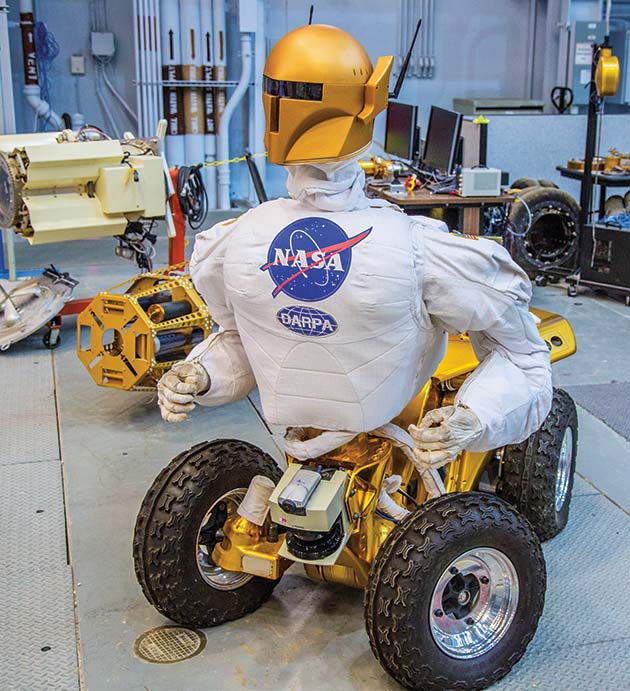

In the Building 9 Space Vehicle Mockup Facility, our group wandered among extraordinary models of the International Space Station, a real Russian Soyuz capsule, Mars Rovers, and spacecraft designed by the private company Space X, which last year began construction on a new rocket launch site in South Texas. Level 9 tourists are allowed onto the floor of the enormous garage, which is about the size of a city block. We inspected a partial gravity simulator, tough-looking rovers, and the Dragon 2, a propulsive cone that resembled a vintage vessel from Flash Gordon.

“We’re moving forward on space exploration,” says Rangel, alluding to questions over recent NASA downsizing and the termination of the Space Shuttle program. “But every time we do a tour, we have one or two who raise their hands who think NASA is shutting down.”

Judging from the activity and energy I witnessed on my tour last fall, nothing could be further from the truth. The White House recently announced its intention to send people to Mars within 20 years, and the surrounding research and test flights to determine mission feasibility make it a busy time at Johnson Space Center.

At the active Mission Control, included as a stop on the Level 9 tour, technicians coordinate and oversee the goings-on for the crew aboard the International Space Station. In a room with abundant computers and 40-foot, flat-screen display monitors, a skeleton crew kept an eye on the orbiting ISS. When compared to the historic Mission Control we also visited, there’s no doubt that audiovisual communication has come a long way since those old Apollo missions.

As the tour continued, we learned about Johnson Space Center’s role in Commander Scott Kelly’s mission on the International Space Station. As of press time, Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko were scheduled to travel to the station in spring for an unprecedented 12-month stay. Most space station missions last six months, but Kelly is part of an experiment to judge the possible impacts of a longer duration of space travel—bone loss and muscular atrophy, for example—as NASA prepares for possible manned voyages to Mars (a journey expected to last 30 months). Meanwhile, Scott’s identical twin brother, astronaut Mark Kelly, will act as the experiment’s earthbound control subject. (Mark Kelly is perhaps most famous for his marriage to former Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was the victim of a 2011 assassination attempt.) Both the Kellys have been prepping for the mission at space center facilities, including at tour stops like the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.

As the tour continued, we learned about Johnson Space Center’s role in Commander Scott Kelly’s mission on the International Space Station. As of press time, Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko were scheduled to travel to the station in spring for an unprecedented 12-month stay. Most space station missions last six months, but Kelly is part of an experiment to judge the possible impacts of a longer duration of space travel—bone loss and muscular atrophy, for example—as NASA prepares for possible manned voyages to Mars (a journey expected to last 30 months). Meanwhile, Scott’s identical twin brother, astronaut Mark Kelly, will act as the experiment’s earthbound control subject. (Mark Kelly is perhaps most famous for his marriage to former Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was the victim of a 2011 assassination attempt.) Both the Kellys have been prepping for the mission at space center facilities, including at tour stops like the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory.

Johnson Space Center is also administering NASA’s Orion Spacecraft program, sometimes called “the new era of American space exploration.” The program made national headlines in late 2014 when the Delta IV Heavy rocket carried an unmanned Orion Spacecraft into orbit. In just a few years, the Orion capsule, which was designed to ultimately make the trip to Mars with four crewmembers, will see its first manned mission.

For Texans, the activity at Johnson Space Center is no big surprise. Since the inception of NASA’s Manned Aircraft Center in 1961, no American city has been more closely associated with the U.S. space program than Houston. From the Apollo moonshots described by David Cisco to the recently retired Space Shuttle program, the center—named after Lyndon B. Johnson for his efforts as a senator to headquarter the space program in Houston—has remained crucial to the broad goals of space flight.

During our stop at the Sonny Carter Training Facility, home of the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory, we watched astronauts in training. The lab is known as the world’s largest indoor pool, measuring 202 feet long, 100 feet wide, 40 feet deep, and holding 6.2 million gallons of water. Next to a submerged life-size mockup of the International Space Station—which is the reason the pool has to be so big—veteran NASA astronaut Stan Love and astronaut candidate Tyler Hague practice moves they hope to use someday in a micro-gravity environment. As Love and Hague work underwater, wearing pressurized suits weighing nearly 300 pounds (and costing $18 million), a team of offshore rig workers practices emergency procedures at the other end of the pool.

In 2008, Love participated in two spacewalks totaling 15 hours to help install a European science lab at the ISS; in 2013, newcomer Hague was selected as part of the 21st NASA astronaut class. “Once you are assigned to a mission, you practice very specific activities,” Rangel explains as we observe the training. “Every move in the suit is an exercise to itself.”

As the Level 9 Tour wraps, I leave the Johnson Space Center with a much better understanding of what it takes to pull off a successful space mission—be it a pioneering trip to a meteor or changing the gaskets on a toilet aboard the International Space Station. Contemplating the night sky, my heart beats a little faster. It’s true, I will never be an astronaut, but as someone who regularly abides the call of the open road, I feel simpatico with those brave men and women who have made it possible for humankind to reach the stars.