(Illustration by Tim Carroll)

Vega to Tascosa

For Oldham County tourism info, call the Oldham County Chamber of Commerce at 806/267-2828.

Boys Ranch

For information on tours of Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, call 806/534-2211. The Boys Ranch Rodeo takes place annually on the Saturday of Labor Day Weekend.

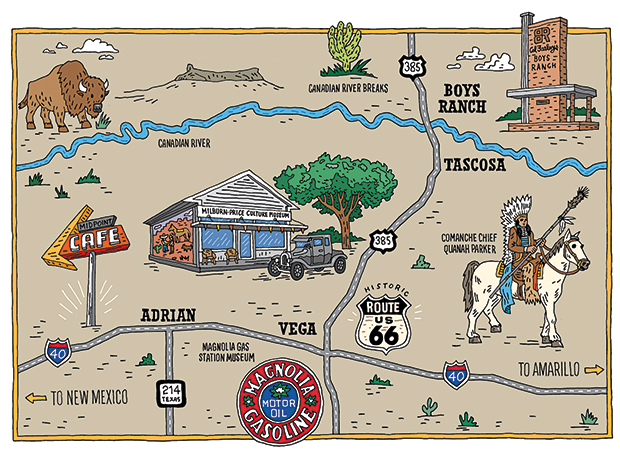

I’m taking the descendent of one of those migratory trails today—US 385—from the grasslands hamlet of Vega to Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, which occupies the ghost town site of Old Tascosa on the Canadian River. Growing up in Vega, I made this journey countless times in the backseat of my dad’s Plymouth. Though I moved away years ago, I return to tend to the family farm in the summer, and this drive always reminds me of the road trips of my childhood.

The route through the northwest corner of the Panhandle is full of stories as old as the bison’s. A country of mesas and canyons, magenta vistas, and big horizons, this part of the Panhandle is also home to one of the largest wind farms in Texas. The 20-mile drive between Vega and Boys Ranch passes the routes of Spanish entradas, Comanche camps, the ancient hunting grounds of the Clovis and Folsom cultures, and ranches dating to the late 1800s.

A good place to start the journey is Vega (population 884), which was founded in the early 1900s. Locals like to remind visitors that Texas sold these lands in 1882 to finance the construction of the Texas Capitol in Austin. The Chicago investors who bought the land developed the XIT Ranch, the world’s largest fenced cattle ranch of its time.

Old Route 66 in Vega.

Across the street from the courthouse is the Magnolia Service Station, originally built in 1924. Now a mu-seum, the building has been restored to its Route 66 heyday with a display of oil cans, tools, tires, an antique cash register, and some of Magnolia’s non-gasoline petroleum products, such as hand lotion. Behind the filling station, a 23-foot metal arrow plunges into the ground beside a historical marker honoring Comanche Chief Quanah Parker. The arrow is one of dozens across the Panhandle that make up the Quanah Parker Trail, a road-trip guide and tribute to the Comanche people, who dominated these grasslands when European explorers first arrived.

From here, I’m drawn to a large mural covering the east side of the building across the street, the Milburn-Price Culture Museum. The colorful mural—one of five around town—depicts the meeting of a Comanche and a Comanchero. The latter were 19th-century New Mexican traders who exchanged goods like guns and whiskey with the plains tribes for horses, bison skins, and slaves.

Museum Director Greg Conn describes the Milburn-Price, housed in a restored lumberyard building, as a “touch museum,” because you can pick up many of the objects. His wife, Karen Conn, meets us at the door for a tour, including the 1923 Model T outside and the printing press inside where you can print your own personal Route 66 postcard. There are artifacts dating to the Triassic period (Oldham County is noted for its fossil fields), giant wooden windmill blades, a horse sleigh, and vintage household items that convey a sense of what life was like in Vega’s earliest days. Particularly striking is the late cowboy Jack Cauble’s arrowhead collection, numbering about 1,000 pieces, including 9,000-year-old Clovis spear points and delicate Antelope Creek points. Linger long and you’ll end up in the back swapping stories with the locals at the two 1930s Formica tables near the vintage popcorn machine. Greg’s always got the coffee on.

Hickory Inn Cafe in Vega.

Driving north from Vega, the landscape changes from farm country into the Canadian River Breaks. The river’s name is thought to be a corruption of the Spanish cañon (canyon), describing the rugged country of canyons and mesas. US 385 offers views of rolling ranch land and jagged arroyos cloaked in mesquite, cholla cactus, and junipers.

When I was a child, crossing the Canadian River was an adventure. There was no bridge. As my family neared the river with its pockets of quicksand, my dad dramatized the approach with tales of lost cowboys and horses, victims of the tricky sands. Our car would slide and spin as he gunned it across the shallow river, we kids burying our heads in our hands. Years ago, two cowboys recovered a Spanish breastplate from the Canadian’s muddy red waters—remnants of the days when Oñate and Coronado navigated the region in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Today a two-lane bridge carries us across the river. Immediately across the river on the east side of the road, a shady picnic area offers a spot to relax beneath cottonwoods. The cottonwoods’ presence dates back to the early Hispanic sheepherders, known as pastores, who planted the trees to protect the settlements they built along the Canadian River banks.

About a mile north of the river, approaching the turnoff to Boys Ranch, the verdant valley to the east helps explain what drew the first settlers here. Among them was Casimero Romero, a New Mexico sheepherder who came in l876 trailing some 2,000 sheep, along with horses and cows, to the rich grasslands along the Canadian. Romero and his family settled on Atascosa Creek and founded the settlement of Atascosa near a spring that still runs today on the Boys Ranch grounds. In the 1880s, Tascosa—the “A” was dropped from the name—grew into a freight distribution hub for surrounding ranches and a rowdy cowboy town with the likes of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett passing through.

To the left of the Boys Ranch gate, a twisted cottonwood marks the site of the now-gone adobe home of Frenchy McCormick, Tascosa’s last resident. A dance hall girl, Frenchy moved to Tascosa in l880 and married Mickey McCormick, a saloon operator. I once knew a man, Roy Turner, who said Frenchy had babysat him when he was a boy. Turner told me that when Frenchy was an old woman and deaf, living alone in what had become a ghost town, tourists would stop by, often frightening her. They usually wanted directions to Boot Hill Cemetery, where the four men killed in Tascosa’s biggest gunfight—an 1886 dispute stemming from tension over a cowboys’ strike—are buried and which visitors can still visit today.

Today, Tascosa is the site of Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, a 12,000-acre residential ranch and school for at-risk children. The ranch has hosted more than 10,000 young men and women since Farley, a former professional wrestler and Amarillo businessman, founded it in 1939. Visitors to the ranch can check out the Julian Bivins Museum, set in an 1884 building that housed Oldham County’s first courthouse. The museum features period photographs and ranching and Native American artifacts. Boys Ranch also offers tours of its historic sites, with stops including the Boot Hill Cemetery and the 1885 Oldham County Schoolhouse, thought to be the oldest adobe schoolhouse still standing in Texas.

Back out on US 385, I drive south back to Vega. Just past the Canadian River, afternoon light catches Saddleback Mountain to the west. Anthropologists believe the Antelope Creek people lived here among the Canadian River tributaries about 800 years ago. In excavation sites on private land, archeologists have discovered farming terraces and points made from stone mined at Alibates, an ancient quarry that’s now preserved as the Alibates Flint Quarry National Monument, 50 miles east near Fritch.

But that’s another trail for another day.