The

Great Historic Hotel Revival

Dedicated preservationists and savvy investors are betting big on bygone destinations, setting off revitalizations in towns across Texas

By Clayton Maxwell

Photos: Courtesy Hotel Settles (left), Kenny Braun (right)

The 15-story Hotel Settles, opened in 1930 during the milk and honey days of Big Spring’s oil industry, towers over this small West Texas town, population 28,000. For decades, the Settles was the only full-service hotel between Dallas and El Paso. Guests included Elvis Presley and Gregory Peck. But the hotel shuttered in May 1980 after the oil crash and the closing of the nearby Webb Air Force Base. The building’s demise seemed to bring the whole town down.

“A lot of people said it would not be savable,” says Tammy Schrecengost, director of The Heritage Museum of Big Spring. “So many campaigned for it to be torn down because it had become an eyesore. It attracted the transients passing through on the train, and there were juveniles tearing it up. It was absolutely awful.”

In 2006, G. Brint Ryan, a Dallas-based tax consultant and entrepreneur, came to the rescue. He purchased the Settles from the city for $75,000, saving it from the wrecking ball. Nostalgia played a part. Ryan is a Big Spring native, who as a boy was a newspaper carrier for the Big Spring Herald and a bagger at the local Safeway. He saw promise in restoring the old structure to its halcyon days and invested $30 million to bring his vision to fruition.

“It was a crazy project that absolutely nobody thought could succeed,” Ryan says. “But I grew up in West Texas. I’m the offspring of a family of settlers that came out there in 1887. My grandfather was as stubborn as an old mule, and I’m the same way. So, when I make up my mind to do something, I do it.”

The hotel reopened, splendid once again, in December 2012. This came after six years of battling piles of dead pigeons, caved-in ceilings, and apprehension from locals. The town still talks about watching each floor light up, one by one, and how cars honked and people cheered across Big Spring when the neon red sign spelling out “Hotel Settles” in capital letters atop the building lit up the night once again.

“It still gives me goosebumps,” Schrecengost says. “Mr. Ryan didn’t just fix it up; he restored it to being the beacon of Big Spring.”

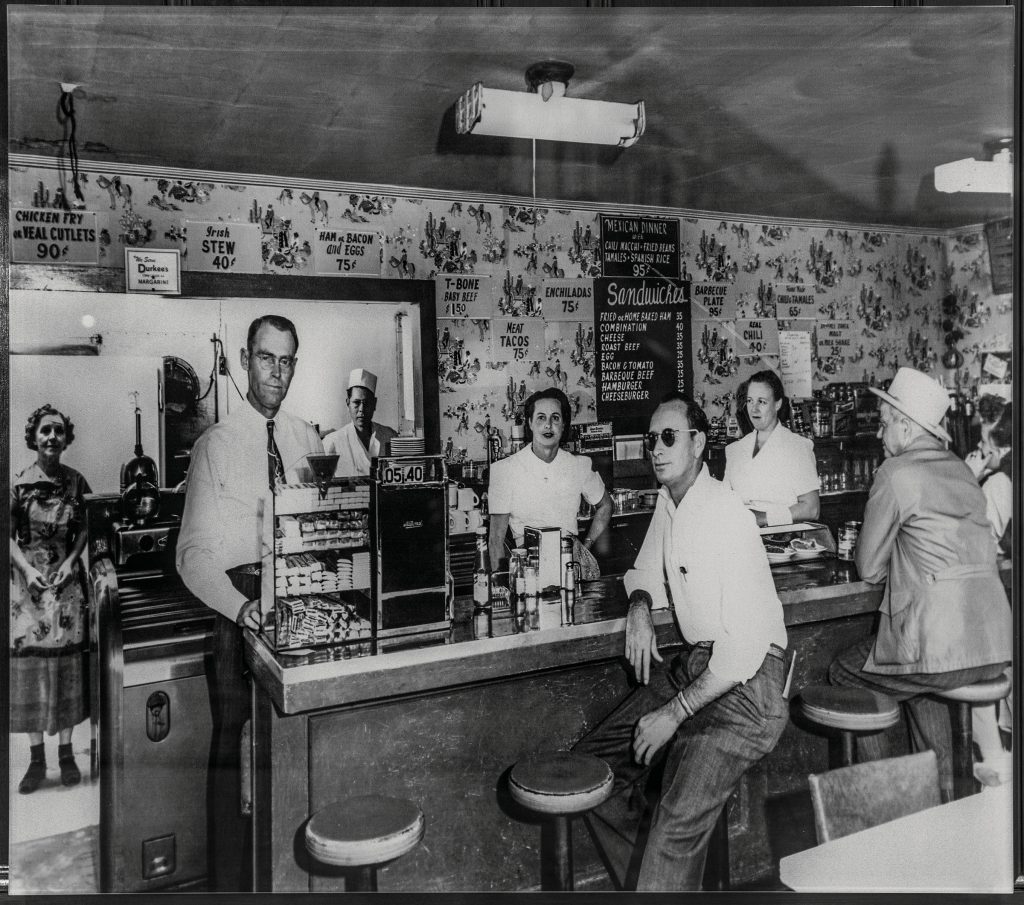

The old pharmacy at Hotel Settles.

Photo: Courtesy Hotel Settles (historic photo)

Yes, there are still bail bonds companies, pawn shops, and vacant buildings from the downturn, but since the Settles reopened, locals and travelers are once again converging on downtown. This summer, the deck of The Train Car, a new cigar bar, was packed with people puffing Cohibas from the Dominican Republic with their cold martinis. Lumbre Bar and Grill was so popular on a Monday night that folks lined up at the door. And the Pharmacy Bar & Parlor at the Settles is not just busy with oilmen and business travelers; it’s the new gathering spot for the city.

“Since the Settles opened, we now have ladies strolling over from the hotel when they’re here for a getaway weekend,” says Jeannie Woodruff, owner of a glamorous Western wear shop named Queens of the Dude Ranch. “It’s nice to have action downtown again.”

Texas is riding a wave of historic hotel revivals. In addition to Hotel Settles, two other stand-out projects—the Stagecoach Inn, built in 1861 in Salado; and The Baker Hotel and Spa, built in 1929 in Mineral Wells—are stirring up excitement among hotel enthusiasts. The former, reopened in September 2018, is the second oldest hotel in Texas and the heart of the artsy Central Texas town. The latter, set to reopen in late 2022, is a derelict marvel that was once a glamorous retreat for those who came to bathe in the North Texas town’s reputedly healing waters.

Laying the Foundation

A passion for saving Texas history drives the developers who are at the helm of these hotel resurrections. They are motivated by current travel trends that favor the types of authentic hospitality experiences these projects afford. Over dinner at the Settles Grill, the hotel’s hearty Western fare restaurant, I talked with a man in a company shirt named Michael Dronet, who was on a business trip from Louisiana, where he works for a firm that performs safety checks at oil refineries. We talked about why he chose to stay at the Settles rather than one of the chain hotels by the highway.

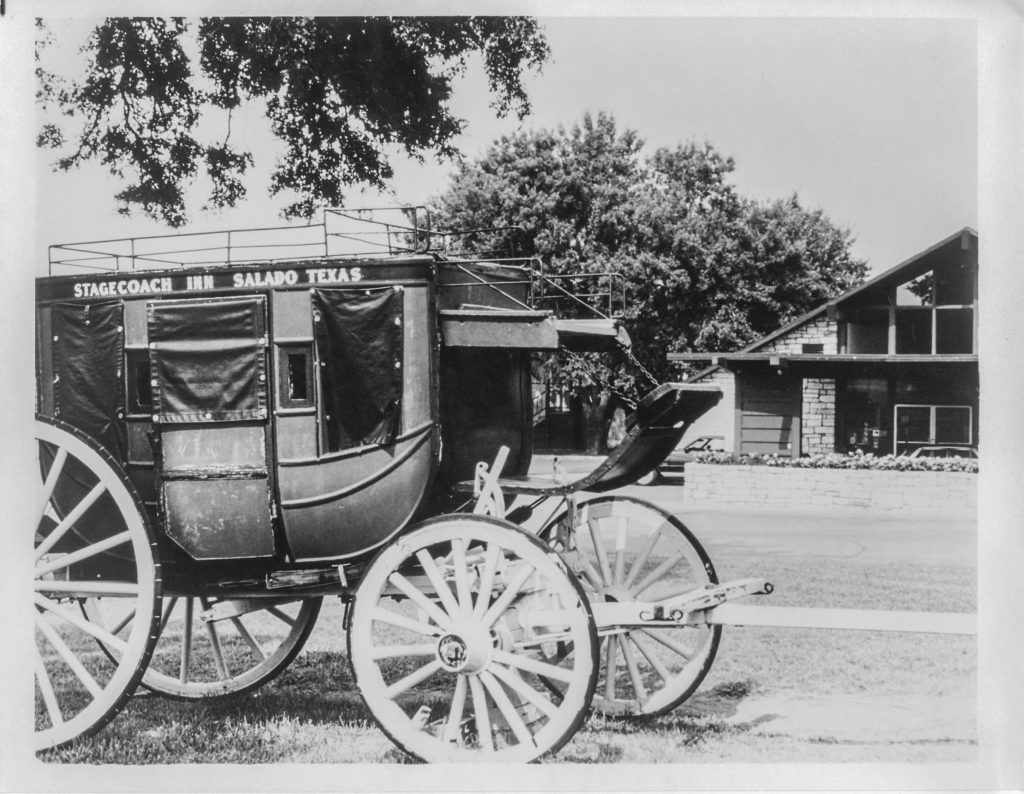

A stagecoach representing the Chisholm Trail era

Photo: Courtesy Stagecoach Inn

“Why stay in a run-of-the-mill, cookie-cutter, do-nothing hotel?” he says. “I am here to do some work, but I also want to know where I am. My friend asked me, ‘Don’t I want to get my hotel points?’ I said, ‘Why? So, I can stay in another generic chain hotel that costs just as much if not more?’”

I later saw Dronet sitting on the porch of The Train Car enjoying the cooler night temperatures and a cigar after a hot July day. He will no doubt go back to Louisiana with a sense of Big Spring, its stories and people. That’s part of the package, explains Jeff Trigger of La Corsha Hospitality Group, an Austin management and consulting company retained for historic hotel restorations. The group’s many projects include Marfa’s Hotel Saint George and Dallas’ Stoneleigh, along with the Settles, in partnership with Ryan.

“There’s a macro trend happening now,” Trigger says. “It’s about experiential travel. The more unique and cool the experience, the more special of a time it is and the better memories you have.”

Said transformations are seeing a heyday in part thanks to tax credits. These incentives make viable the costly, time-intensive resuscitation of buildings rich in detail that few craftsmen can replicate today. Developers’ efforts can provide a significant economic boost to small communities through construction, new hospitality jobs, and tourism.

The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives Program, instituted in 1976, provides a 20% tax credit for the rehabilitation of a historic building for an income-producing use. In 2013, Texas realized it could go bigger, and the 83rd Legislature passed the Texas Historic Preservation Tax Credit Program, which gives a 25% tax credit for the rehabilitation of certified historic structures in Texas. The Texas Historical Commission has certified more than 200 projects across the state since that law went into effect in 2015, with more than $1.5 billion in qualified expenses and more than $2 billion in total construction costs.

Jane Hickie, a prominent attorney and former campaign advisor to Governor Ann Richards, calls the law the third best the state has ever passed—after Right on Red and Liquor by the Drink.

The combined federal and state incentives make it worthwhile for investors to give these treasured Texas hotels a second chance. The Fredonia Hotel in Nacogdoches, The Driskill in Austin, and The St. Anthony in San Antonio were all restored with the help of some form of these federal and state tax breaks.

“Texas has the best overall program for restoring historic buildings,” Ryan says. “So, you’re seeing somewhat of a renaissance now in the state driven by all of these tax-credit resources that are available at the federal and state level.”

Stagecoach Inn

Clark Lyda’s mother often took him to dine at the Stagecoach Inn when he was growing up during the 1960s. More than 30 years later, Lyda—now an Austin-based developer—was still eating at the Stagecoach, but he was taking his mother instead. Eventually her health declined, and she could no longer make the trip.

A ranch-style guestroom at The Stagecoach Inn. Photo: Kenny Braun

“I have a real attachment to it, and to Salado,” Lyda says. “To me it is one of the last pieces of old Texas that seems authentic and moves at a slower pace. I saw that it was going to die. I didn’t want that.”

Formerly a stagecoach stop on the Chisholm Trail, the hotel is known for its storied guest list including Jesse James and Sam Houston, and classic menu items like tomato aspic and strawberry kiss meringue. It had long brought people from the cities to shop in Salado’s galleries and boutiques, but in 2000 there was an unpropitious turnover to new owners. Add to that five years of highway construction to widen Interstate 35, which runs mere yards from the back of the hotel, and the Stagecoach began to lag. Rooms were sorely in need of modernization, and occupancy rates trickled to almost nothing. Salado businesses felt the sting of the hotel’s dwindling occupancy.

Then in 2015, Lyda and his partners, David Hays and Austin Pfiester, bought the property. They brought in Trigger from La Corsha Hospitality Group to embark on an overhaul that will total approximately $30 million once additional projects are completed in the fall of 2021, including an outdoor pavilion, conference center, mineral pool, and 60-room addition to the hotel. They started with the opening of the restaurant in 2017, with a new culinary direction. David Bull, co-owner of Second Bar + Kitchen in Austin and vice president of culinary operations at La Corsha, kept the signature meringue on his modernized menu, which also includes a swoon-worthy hibiscus margarita. In 2018, they reopened the hotel, having revamped its once musty 48 rooms, which start at $129, into Saltillo-tiled ranch-style retreats inspired by the midcentury modern architect Cliff May.

A SCI burger from The Stagecoach Inn restaurant. Photo: Kenny Braun

The rebirth has paid dividends throughout Salado, population 2,300. Hotel tax revenues between October 2018 and July 2019 jumped 56%, plus the hotel employs 43 people—from waiters to front desk attendants to housekeepers—providing essential jobs to a small town. The artisan boutiques and galleries Salado is known for have also benefited since the hotel’s reopening on Labor Day weekend 2018. Sales taxes from the second quarter of 2019 were 25% higher than that same period the previous year, just before the hotel opened, suggesting a resurgence for retail.

“I think of my mother every time I’m there,” Lyda says. “I think she would be happy about this even though it’s a little crazy. I know all of us who are involved are proud of it because it’s not just a real estate investment. It’s preserving a piece of Texas character that we all have enjoyed and we hope other people will get to enjoy, too.”

The Baker Hotel and Spa

Perhaps no other project is stirring up more buzz statewide than The Baker Hotel and Spa in Mineral Wells, population 15,000. This glorious but crumbling 14-story Spanish Colonial Revival gem had been in a stalemate for 12 years as developers tried to piece together the complicated financing puzzle. A solution was finally reached in June 2019, when Baker Hotel Holdings, LP bought the property and embarked on a $65 million restoration.

This group includes familiar names: Ryan and Trigger. There is also Randy Nix, a longtime Mineral Wells businessman. Nix is also restoring the town’s Crazy Water Hotel and in 2018 opened a shopping emporium called The Market at 76067 in the historic downtown. He’s played a pivotal role in localizing the effort.

“I go to Mineral Wells now and you can feel a groundswell,” says Laird Fairchild, the project lead. “There are fun places for dinner and bands playing. Randy says that the rest of downtown can’t thrive without The Baker Hotel, and The Baker Hotel can’t thrive without the revitalization of downtown. The feeling we had that we were on the right track has transformed into knowing we’re on the right track.”

The project has even drawn the attention of Hollywood. Los Angeles-based production company Two Stone Media is filming a docuseries about the Baker’s unthinkable comeback, which is being shopped to networks. Resurrection, Texas will follow the highs and lows of restoring the Baker and its impact, emotional and economic, on the local community. In the trailer, now viewable on The Baker’s website, Trigger says, “You’re going to see jaws drop.”

He’s talking about the outdoor mineral baths, an almost 10,000-square-foot spa, the vision of top-of-the-line architects Kurt and Beth Thiel, and more than 150 guest rooms starting at $170. No hyperbole: This could be the biggest hotel resurrection in Texas so far.

Hotel Settles

Hotel Settles was humming when my 9-year-old son and I checked in last summer. Boot-clad, cowboy hat-wearing oilmen came and went. Country music filled the grand lobby, where a magnificent double-sided staircase with intricate gold plaster flourishes evokes the hotel’s past as a gathering spot for the well-to-do. A striking 10-foot oil painting of Ryan’s mother reigns over the palatial staircase.

More than seven years have passed since the Settles opened its doors for a second act, with 65 guest rooms starting at $341. As of July 2019, the hotel tax revenue in Big Spring has gone up 43%, while the sales tax revenue has increased by more than $1.5 million. These numbers can’t be solely attributed to the Settles, but many locals link recent growth in downtown Big Spring to the rebirth of the hotel.

“The hotel is probably the first thing in 50 years to redirect traffic from Midland and Odessa,” Ryan says. “We’ve had strong positive cash flow since about six months after we opened. Last year was the most profitable year we’ve had with the business. So, the idea is to continue the development around the hotel, to make it a place where people want to come.”

When my son and I were scouting potential hiding places on the Settles’ mezzanine for a game of hide-and-seek, I overheard a man checking in at the front desk below. He’d just come back to Big Spring after many years away and peppered the concierge with questions.

“Who owns this place? Who is that woman in the painting? How much of this staircase is original?”

Later, piano music filled the lobby as we were heading out to the Settles’ swanky new pool. That same inquisitive man had plopped himself down at the baby grand on the mezzanine and was playing gorgeous, complicated classical music that floated through the hotel, the same one that just a decade ago sagged beneath caved ceilings and dead pigeons. The beauty of it made us stand still and listen, transfixed. Preservationists set the stage for moments like these when they decide to bring a historic hotel back to life. In a world of chain hotels that mostly all look and feel alike, it’s magic that’s hard to come by.

What’s Old Is New Again

In 1978, JP Bryan, a historical preservationist and entrepreneur, bought the Gage Hotel in Marathon, built in 1927 by celebrated Texas architect Henry Trost. Bryan has transformed the Gage into what may be the most beloved historic hotel in Texas and created a portal to West Texas. gagehotel.com

The Sinclair, a 1929 art deco office building in downtown Fort Worth, opened in November 2019 as a 15-story luxury hotel. The Sinclair seamlessly blends the most advanced in technology (Bluetooth speakers in the bathroom mirrors) with Gatsby-like decadence. thesinclairhotel.com

Hotel Paso del Norte, built in 1919, also by Trost, is the grande dame of El Paso hotels. The property is in the midst of a major overhaul and is set to reopen in May 2020, with new views overlooking Mexico from a deluxe rooftop bar and swimming pool. hotelpdn.com