The Port Aransas Nature Preserve is a 1,280-acre birding hot spot. Photo by Texas Department of Transportation

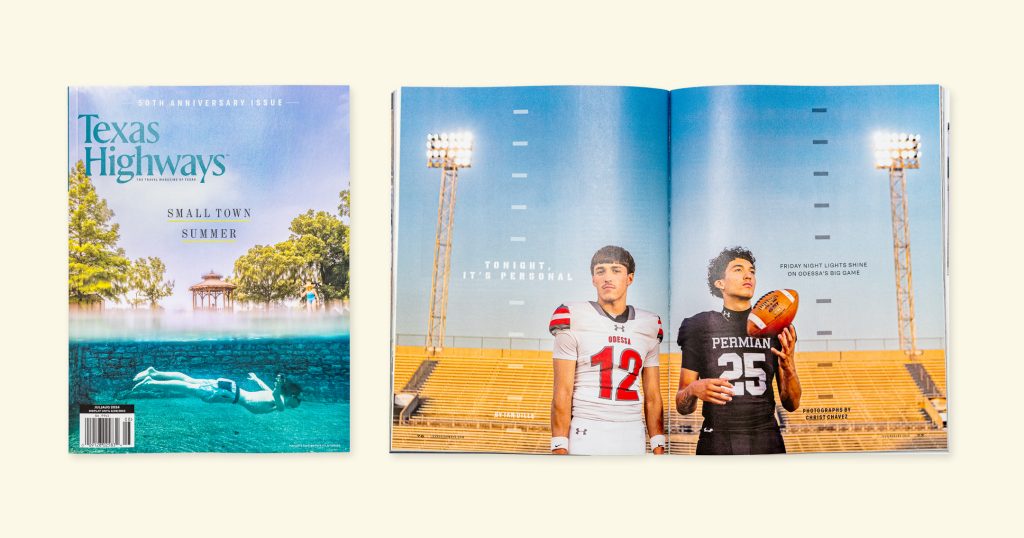

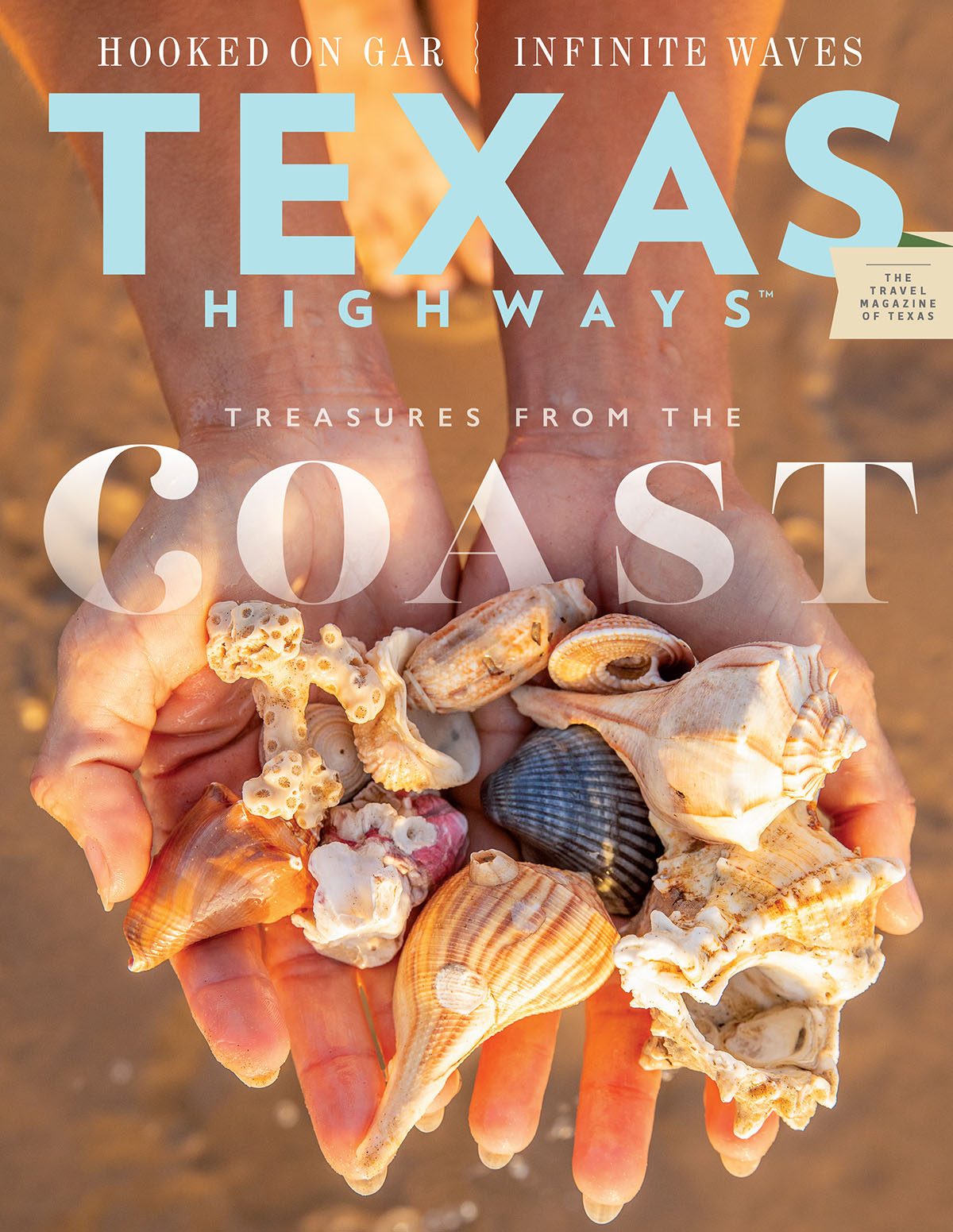

The last of the migratory birds resting, eating, and let’s face it, luxuriating in Port Aransas were taking to the air and continuing north before summer when I visited the Gulf Coast town in mid-April. Although I’m familiar with Mustang Island, an 18-mile sliver of land that includes Port Aransas and separates Corpus Christi Bay from the Gulf of Mexico, it was my first trip out to the Port Aransas Nature Preserve. With the island being an important stop along the Central Flyway, a major flight path in North America for untold numbers of birds every spring and fall, the nature preserve helps protect coastal wetlands and prairie grasses, thus ensuring a welcoming biodiverse setting, especially if you’re a bird. Or a bird watcher.

Living in landlocked Hays County, where I can usually tell a hummingbird from a grackle, I’d certainly call myself bird curious. I visited the four locations of the roughly 1,280-acre nature preserve—Charlie’s Pasture, Leonabelle Turnbull Birding Center, Joan and Scott Holt Paradise Pond, and Wetland Park—and found them all teeming with beautiful birds I’d never seen nor heard of. I wasn’t alone in my fascination.

“I got addicted last year to shooting birds,” George Helton told me while sitting with a group of fellow birders in the birding center. Helton was armed with a camera and lens the size of a coffee thermos aimed at, according to him, a male indigo bunting surveying a downed tree limb about 20 yards away. “It’s the challenge,” he said. “These birds hardly ever sit. Today, they’re jumping everywhere.”

Fulltime RV-er George Helton shoots birds at the Port Aransas Nature Preserve. Photo by Anthony Head

Helton is a full-time RVer and Winter Texan, and this is one of his favorite places to be in spring. After naming off a dozen different bird species he’d spotted—yellow-throated warblers, double-crested cormorants, herons, orioles, egrets—Helton urged me toward the boardwalk extending into a freshwater marsh. “Watch out for Boots,” he said.

“Boots” is a male American alligator, roughly 10 to 12 feet long, that likes this area of the local wetlands and may possibly be the same alligator that was spotted when the birding center was built in 1994, although no one knows for sure. He didn’t appear for me, but I did get to see a variety of waterfowl cavort among the southern cattails and saltgrass, apparently cool with sharing space with a hiding reptilian monster.

Tucked away off Channel Vista Drive, Joan and Scott Holt Paradise Pond is two acres of freshwater wetland and native black willow trees. An hour easily passed while I sat watching songbirds, butterflies, and dragonflies go about their busyness. At nearby Wetland Park, another quietly reclusive preserved area off State Highway 361, there’s a boardwalk and gazebo for observing marshy tidal flats. During my visit, water gently rippled from salty ocean breezes and dozens of birds waded, preened, and occasionally took flight.

On blackboards, I saw where visitors report their daily bird sightings (visitors can also track the bird species they see with this handy birder checklist). But even though signs posted at each location assisted me in identifying birds and native plants, it was still tough keeping track of different colors, shapes, and sizes of wings, beaks, and tail feathers.

Rae Mooney, the nature preserve’s manager, told me later, “We have days when we’ll see 100 different species. Over the years, 275 different species have been observed here. Many of them are here year round.”

Mooney, who is in the field regularly with her staff for boardwalk maintenance, educational birding programs, and habitat restoration, said three preserve components are now connected by hiking and biking trails, thanks to ongoing improvements (the exception is Wetland Park).

Birders at the Port Aransas Nature Preserve’s birding center boardwalk. Photo by Anthony Head

Another major project is underway in what was perhaps my favorite section, Charlie’s Pasture. At the entrance to this location, only a few hundred yards from the shipping channel, I found the large pavilion that serves as a gateway to over 1,200 acres of salt marshes and sandy tidal flats with as much color from prairie grass, butterflies, and wildflowers as from the birds. It’s also where thousands of shorebirds, like the endangered piping plover, spend winter. The Salt Island Trail (destroyed by Hurricane Harvey in 2017) is being rebuilt all the way to the isolated observation tower in the middle of the preserve.

“The birders are very excited for this trail to be restored,” Mooney said, noting its November completion date. “We have to be done by then because of the whooping cranes that winter here.”

I look forward to seeing those cranes. Until then, the summer and year-round avian residents—least sandpiper, common nighthawk, roseate spoonbill, purple martins, among a few others—get the place to themselves. Say what you will about Port A being a great destination for swimming, boating, fishing, and surfing. For some of us, it’s strictly for the birds.