Illustration by Brian Lutz

He’s the bard of the Hill Country—a satirist, author, singer-songwriter, raconteur, and equal-opportunity offender. He’s run for Texas governor, not to mention state agricultural commissioner and Kerr County justice of the peace. Kinky Friedman is a larger-than-life figure, a wise-cracking product of the land that he’s lived on and loved most of his life.

Friedman grew up on Echo Hill Ranch—the summer camp between Kerrville and Medina that his parents opened in 1953—and attended the University of Texas at Austin. He then joined the Peace Corps and served in the Pacific island of Borneo, where he introduced the locals to Frisbee. Back in Austin in 1973, Friedman took part in the great progressive-country music explosion with the debut of his satirical band, Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys.

Friedman’s classics, such as the feminism parody “Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in the Bed” and “They Ain’t Making Jews Like Jesus Anymore,” landed the band a performance at the prestigious Grand Ole Opry. He later joined Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue for two years. By the end of the ’70s, Friedman had parked it in New York City, where he launched his literary career, mainly writing detective novels that starred himself as the lead character.

Friedman eventually returned to Texas and wrote a humor column for Texas Monthly, which set the stage for his 2006 gubernatorial campaign. He ran as an independent with the campaign slogan “How Hard Could It Be?” and garnered 12% of the vote.

Friedman now lives back on Echo Hill Ranch. The summer camp closed in 2013, but Friedman and his sister, Marcie Friedman, revived the camp last summer specifically to welcome “gold star kids”—the children of parents who either died in military service or as first responders on duty. The camp is staffed by both civilian and military volunteers, says Marcie, the volunteer camp director and a foreign service officer for the U.S. State Department. After hosting 62 children from 14 states last summer, the camp is gearing up for about double the number of campers in its second summer. “I’m just now realizing that this is maybe what I was born to do,” Kinky says.

TH: How did you spend the pandemic?

KF: I’ve been doing a lot of recording, and I’m writing. I just completed an album titled The Poet of Motel 6. Also, me and [the late] Billy Joe Shaver have a new record out, Live From Down Under, with songs we recorded live in Australia about 20 years ago. This was right after Billy Joe’s son and guitarist, Eddy, died. The doctor told him, “Don’t go to Australia with the heart condition you have.” I told him just the opposite. It was one of my last good decisions. It was the right thing to do for Billy Joe—get away from the tragedy and trauma.

TH: Tell us about the changes at Echo Hill Ranch.

KF: That’s been the major move in my life. My parents, many years ago, had a camp here for boys and girls. It started in ’53 and ran for about 60 years. It’s been closed for 15 years. It’s not just a place, but the dream of my parents, Tom and Min Friedman, since I was 6 years old. My sister, Marcie, and I are attempting to get this running again. The gold star program is one we’re deeply involved with. We think when someone is killed in the military, their kids tend to get lost in the shuffle. We’re dealing strictly with kids and strictly with fun. Later this summer, we’re going to have a camp for children of Afghan refugees and other kids in need. Both programs are totally free. That’s what differentiates them from some other summer camps.

TH: What happened to the Utopia Animal Rescue Ranch, which was based at Echo Hill for almost 20 years?

KF: Thousands of dogs came through here over the years. The problem was the place is too far for people from the cities to come by and adopt dogs. So we transferred over from being a rescue ranch into a menagerie. We have a program—not official—called canine therapy. The dogs get to come inside, they hang out with the kids, they go on the cookouts, they do everything the kids do. We just lost my favorite, a chihuahua named Duke of Echo Hill.

TH: Are you moving into full-time charity work by reviving the camp?

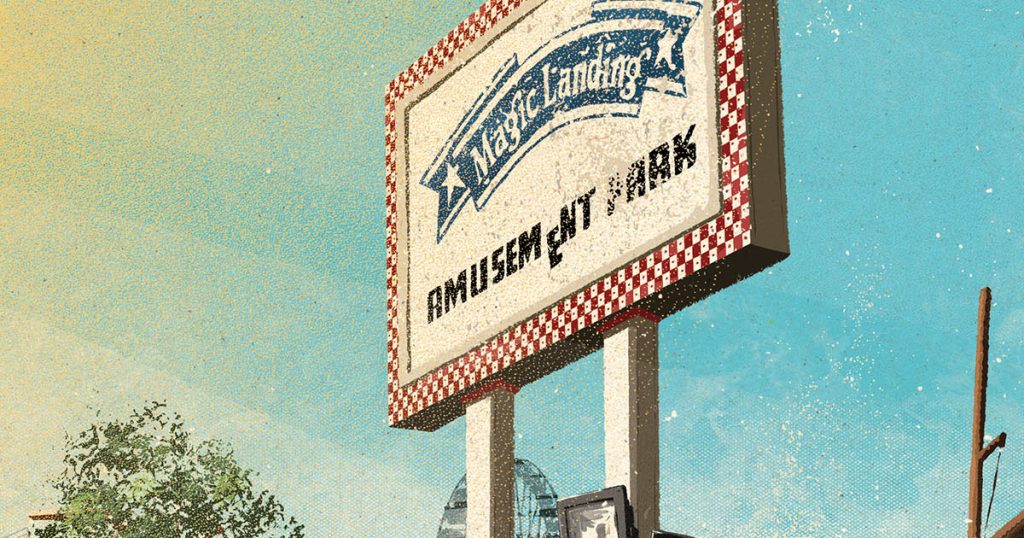

KF: It’s a pointed issue—what you want to do with the remaining days of your life. If you buy into that. Well, obviously, I’m 76 years old. But I read at the 78-year-old level. The ranch had become like an old amusement park that had fallen into disarray. But now, I think our parents’ dream is coming close to being realized.

TH: It’s an all-volunteer effort?

KF: Yes. Everyone’s been great. There was a volunteer who fixed a water heater who I went over to thank. He said, “You’re welcome. I’m doing it for Jesus.” I told him, “I’m doing it for Moses.” We went to our separate corners and been friends ever since. The people that volunteer to help us, if they’re good Christians, be a good Christian. Be a good Jew. Be a good Muslim, and do things for America, and for yourself. We’ve been deeply inspired by these people. The staff is more inspired by the kids than the other way around. Nothing against any of the bigger programs, but “No Shrinks Allowed” here. Just fun. We want to deal with having a good time, making friends. Now of course I’ve gotten serious about the whole thing. I’m a Gandhi-like figure flitting through the landscape.

TH: What’s your first memory of the Hill Country?

KF: Cowboy stars. If you come from Houston or any place like that, the stars are unusual, even more so if you’re coming from outside the state. As my sister likes to say, a happy childhood is the worst possible preparation for life.

TH: What’s your favorite Hill Country drive?

KF: My dad always felt the drive from Kerrville to Medina [on State Highway 16] was one of the most beautiful in the world. And it still is. Gorgeous, yeah.

TH: What is your favorite secret Hill Country spot?

KF: If things weren’t changing so quickly that would be easy to answer. I can remember when “Hill Country” was a pejorative. People didn’t want Hill Country anything. That wasn’t so long ago. Today, you can go 10 feet in any direction on the outer fringes of Austin and San Antonio, and everything slaps “Hill Country” on it. Most of us don’t want to Californize Texas if we can avoid it, but it’s getting to be looking a little too late.

TH: Are you an optimist or a pessimist about the future?

KF: Things are changing in a good way. For instance, all the gold star kids who have joined the Echo Hill Mountain-Climbing Association, which was founded in 1953, get a card. That means you’ve climbed Echo Hill, the tallest in the area. Many of these kids painted stones at the summit to honor the memory of their mother or father and placed it on top of Echo Hill. You will be moved by the experience. It teaches you that the little things are really important. We’ve got all these kids who’ve lost a parent, who have never been to a sleep-away camp. We’re talking about a big hole in the world that’s hard to patch. We’re trying to do our part. By the way, we’ve got a couple jobs open for you.

TH: Seriously?

KF: Everybody who wants to help has an invitation. You don’t have to commit to anything. In charity work, money is always important. But energy and giving of yourself may be just as important. As I always like to say, time is the money of love.

Keep up with Kinky Friedman’s escapades at his website, kinkyfriedman.com.

Learn more about Echo Hill Ranch summer camp and its opportunities for gold star kids at echohill.org.