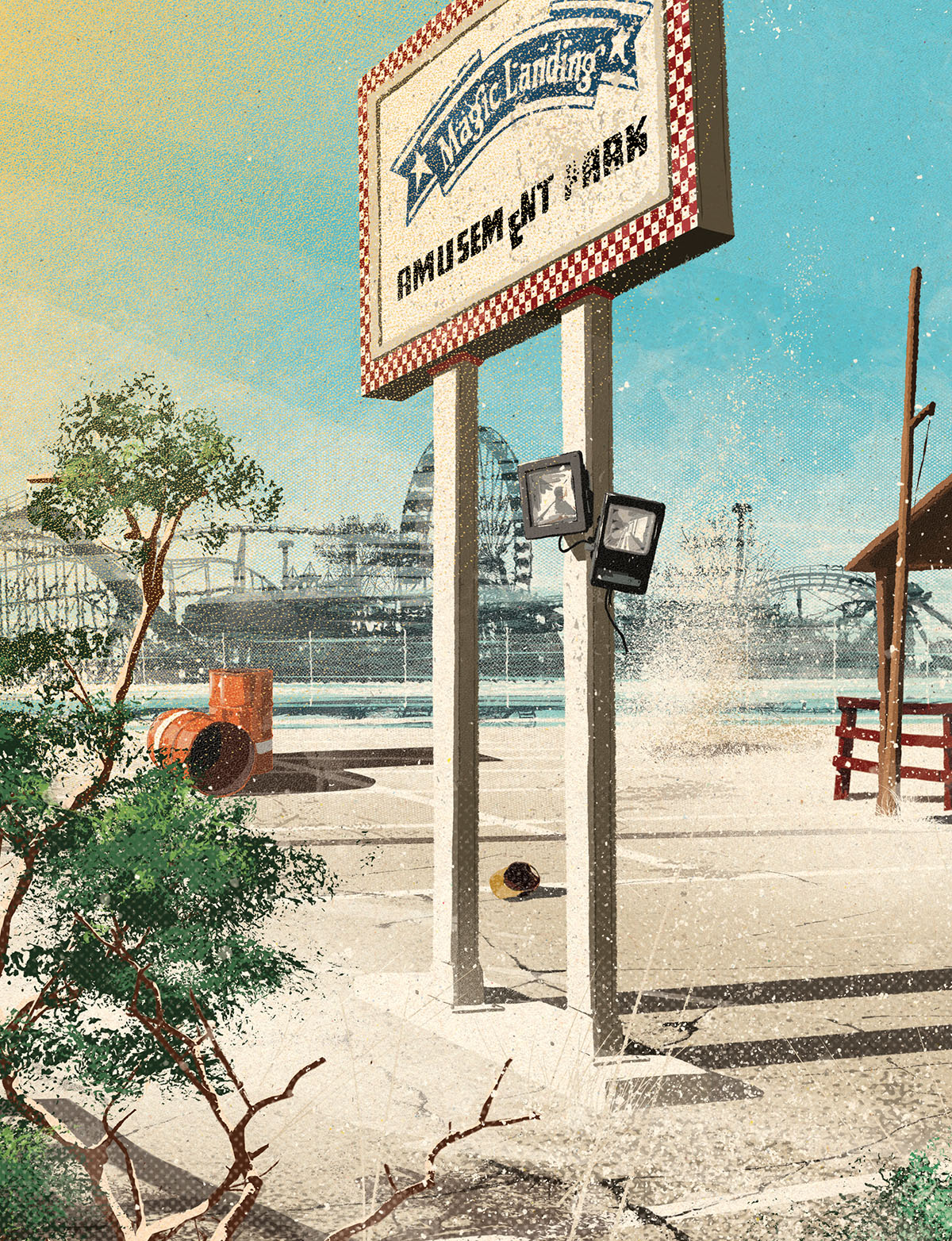

Illustration by Mark Smith

The Great

Escape

Magic Landing came and went like a desert mirage

When I was in elementary school and we lived in Colorado, I spent three consecutive summers in Juárez, Mexico. Since my parents worked, there was no one to watch me. So, when school let out, my parents drove nine hours to El Paso, then across the border to Juárez, where they dropped me at my grandmother’s house.

With so many people there—grandparents, great-grandmother, aunt, cousin, and three uncles—there was always something going on. Always someone yelling. Always an uncle to wrestle with. Always another uncle who’d jam dirty socks in my mouth when I tried to sleep. That always made them laugh.

“A DORMIR!” my grandfather’s voice would rumble from across the hallway. He was a butcher who left home hours before sunrise, so he’d be in bed before sunset. Whenever my uncles and I got too loud, he’d yell at us to go to sleep.

I had trouble sleeping. Not because of the dirty socks, though that didn’t help, but because of the heat. There was no air conditioner, and the box fans on the open windowsills only did so much. The front and back doors were left open for the wind to rush through, but that also wasn’t enough. During the day, the heat could reach triple digits. At night, the heat could wake you and make you wonder if anyone would notice if you went outside, turned the hose on, and drenched yourself in water.

A couple of summers ago, when the air conditioner at my home in El Paso broke during the middle of the night and I woke up covered in sweat, I was reminded of those summers in Juárez. That heat is one of two things I remember most from those days.

Not too long ago, if you drove on Interstate 10 in east El Paso, looking toward Juárez, there was little to see. Besides the lonely road connecting home to the rest of Texas, it was mostly the barren Chihuahuan Desert. But in the early 1980s, developers and consultants came up with the idea to build an amusement park there called Magic Landing.

El Paso has almost 300 annual days of sunshine, so the park would be open most of the year. Closed “only when the good Lord sneezes too hard,” is how George Dipp, the park developer, explained it to the El Paso Times in 1984. That’d be most of March and April, when the wind blows so hard it can rip roofs off buildings.

Once complete, Magic Landing was projected to bring in around a half-million visitors a year. It’d sit on 80 acres, half the size of Disneyland then. There’d be rides, a roller coaster, an amphitheater with six stages, and air-conditioned restaurants and stores. Magic Landing would have its own characters—a bear, a wizard, and Taco Duck—and an 1850s replica steam-engine train that could carry 200 passengers. There’d also be a Ferris wheel so big and shiny—15-and-a-half stories, 40,000 light bulbs—you could see it from miles away. Of all the Ferris wheels in the world, only the Colossus at the New Orleans World’s Fair would be taller.

Most audacious of all, Magic Landing promised an 188,000-square-foot lake with boats to help ease the unrelenting heat. Water is the most precious resource in the desert, so the lake seemed especially bold. But in the context of everything Magic Landing promised—a symbol of El Paso’s bright future—the lake also felt like it was exactly where it belonged. After all, the park’s motto was “You Will Believe in Magic.”

Following years of planning and developing, the park would go from a mirage in the desert to a reality—at the cost of $10 million. The vastness of the wide-open West Texas desert seemed like the perfect place for Magic Landing.

I don’t remember the first time I heard about Magic Landing, but it must have been from radio and television commercials. This was during my sweaty summers in Juárez, of that I’m certain. As certain as I know visiting the park was one of the first things I ever truly desired.

Even as a 9-year-old, I knew enough to not ask about visiting Disneyland. That wasn’t realistic. I may as well have asked to live in a place with a temperate climate instead of in this dry desert heat. But Magic Landing was different. The park was just across the border.

From the moment I learned of its existence, it took over my thoughts. I became obsessed with Magic Landing in that peculiar way something enters your young, impressionable mind and never leaves. There was something about it that I had to see. Something more than the rides, the Ferris wheel, the lake, everything else. I didn’t have the words then, but years later I recognized what I felt: the desire to escape.

Escape from the heat. Escape from the sinking feeling that once summer ended, months would pass before I’d see my relatives again. Escape from knowing that every day after school, I’d return to an empty house in Colorado with my little brother and instructions from my parents: Don’t turn on the stove or open the door for anyone. We’ll be home soon.

I wanted to break free and go somewhere that even if it was still in the desert, seemed like it was in another realm. I thought about that place often. Sometimes, I’d see it when I closed my eyes.

Developers said constructing Magic Landing was like creating a city. Before a single person could visit, they had to build an entire infrastructure.

On land that was among the cheapest in the area, workers dug holes deep into the desert—and, like magic, water appeared. They leveled the ground, covered it with asphalt and wet cement that hardened to concrete. They built electrical, gas, and sewer systems. After those trenches were dug and pipes run underground, El Paso expanded its own plumbing, connecting to what, not long before, had been a desolate landscape. The city had a lot to gain from the economic boom of Magic Landing.

Almost since its beginning, El Paso has existed as a way station. Its given name, El Paso del Norte—Pass of the North—underscores this. Native American trading routes, established around 1000 A.D., crossed through here. From the late 1500s to the late 1800s, Europeans, mostly Spanish, used the same route on their way to colonize, proselytize, and search for cities made of gold. Not everyone made it. In part because of the heat and lack of water, this 90-mile stretch of desert was so brutal that those who survived called the trip Jornada del Muerto—Journey of the Dead Man. Since then, El Paso and Juárez have tried to answer their age-old problem: How do you attract new people to the desert and keep the ones who are already here from leaving?

If all went well, Magic Landing could be part of the answer. It could persuade people El Paso wasn’t the edge of the country but rather the center of a region, attracting visitors from a 350-mile radius across northern Mexico, southern New Mexico, the Panhandle, and the Permian Basin. Other places full of people who felt just as isolated. People who perhaps couldn’t afford Disneyland but had enough money for Magic Landing. The park would also provide hundreds of jobs to residents parched for opportunities. So thirsty in fact, 5,000 job applications were submitted.

That was the vision for Magic Landing. An oasis of entertainment. An island of fantasy. The finest family park in the Southwest.

In my dreams, I walked down Magic Landing’s gleaming streets. Surrounded by dozens of new buildings, I ate pink-colored cotton candy, a bright swirl against the dusty desert landscape.

In my dreams, I rode down the log flume and in bumper boats, the water splashing me cool. I rode the roller coaster and felt the wind rush over my face. I rode the steam-engine train on the elevated tracks circling the park, always looking inward to where everything was, never outward toward the endless desert encircling us.

In my dreams, I existed in the magical place until sometime during the middle of night the heat shook me awake. And just like that, I felt the sweat around my neck and on my back. I was done dreaming and frustrated by the lack of relief.

I’d get up, walk to the bathroom, and splash water on my face and chest. Sometimes out of desperation, I’d lie on the living room’s cold tile floor in just my underwear. I’d lie there and, as if it were simple to control what we see when our eyes close, I’d think of Magic Landing while willing myself to fall asleep again.

We interact in odd ways with the things we imagine. My dreams of a place in the middle of the desert weren’t too different from many others who have seen the same barren place and imagined all it could be. The turning of nothing into something.

The desert is a contradiction. It attracts scammers and loners. It’s awe-inspiring because it hides nothing. Yet when the wind mixes with the dirt, it hides everything so you can’t see what’s buried. It’s beautiful but dangerous. You can die from its heat or its cold.

The desert holds our complicated relationship with existence. In the nothingness, some see endless potential, while others see only an unforgiving land. Out there, one day can be idyllic, making you believe anything is possible. In the sun, the absurd seems magical. And then the very next day, you’re fighting against the wind. In the dust storms, the desert becomes an endless yell. On those days, nightmares chase the dreamers away.

From the start, things at Magic Landing didn’t go as planned. The Memorial Day grand opening was delayed because the wind howled too loudly, pausing ongoing construction. When Magic Landing finally opened on July 4, 1984, admission was free because the rides weren’t ready.

Despite workers scrambling to finish the park and 40 mph winds that made the 99-degree heat feel like a blowtorch, 30,000 visitors arrived that first day. “It looks kind of empty now,” one of them told the El Paso Times, “but in a few years it should be real nice.”

Had Magic Landing gone on to operate for decades, perhaps people would’ve forgotten that the park wasn’t ready when promised. Forgotten all the kinks that had to be worked out. That rides malfunctioned. That the power shut off. That rain-check policies were unclear. Magic Landing could have recovered. But everything changed the following year.

It was a Monday, so the park should’ve been closed. But because it was Labor Day and summer’s end, Magic Landing opened its doors. Around 6:30 p.m., someone on a roller coaster allegedly lost their hat, and it landed on the rails. Frank Guzman, an 18-year-old who’d worked at the park since it opened, climbed the ride to retrieve it.

According to park officials, the roller coaster struck Guzman and severed his arm. Almost immediately the ride stopped. “Nothing happened, nothing happened,” park employees told visitors as medical personnel, police, and firefighters escorted passengers off the ride. An hour later, the sun set. A couple of hours after that, Guzman died.

Imagine the dreadful sight. Guzman, an incoming senior who had played on the Bel Air High School football team, fatally hurt in a place built for magic. Blood seeping into the thirsty desert. The military helicopter taking Guzman away, leaving clouds of dust and dirt whispering in the air.

Guzman’s parents disputed the park’s version of how their son died. His mother said she was at the park when the tragedy happened and saw people running toward the ride. She screamed for her son as employees kept her from him. For an hour, she yelled for someone to get him help. The father later claimed his son was struck in the head and other employees told him Guzman was on the roller coaster not because of a hat but because a cart was stuck. The sheriff’s sergeant, other investigators, and even witnesses alleged they didn’t see a hat.

Magic Landing’s owners didn’t comment. Years later, they settled a lawsuit with Guzman’s family. Park owners said nothing of the hat, as if it was one of those desert apparitions.

Not long ago, if you drove on Interstate 10 in east El Paso, looking toward Juárez, you could see the ruins of an amusement park. A place that lost its magic when a young man died, insurance rates climbed, prices rose, and the number of visitors dropped. Eventually, the park didn’t qualify for insurance. In its final days, it was so empty the hot dog distributors said it wasn’t worth the time to drive there to restock. In 1989, Magic Landing was listed for sale in an amusement park trade magazine. There was no asking price, just the park’s phone number in an advertisement that called it a “Disney-type” place.

For the rest of the ’80s and into the ’90s, there were rumors Magic Landing would reopen. Rumors it would rebrand as an Old West theme park or be torn down and replaced with a Six Flags or another park based on Star Trek. It could work, people said, but it never happened.

Instead, Magic Landing’s remains slowly faded until all that was left was an empty ticket booth, buildings covered in plywood, and random memories. Some of the rides were auctioned off, and the human-made lake evaporated. The dreams of what could’ve been had been chased away.

Some people started calling it Tragic Landing and swore it was haunted. They’d go out there looking for ghosts. Others went out and set fire to what was left. Some of the fires burned for hours, so big and bright you could see them from miles away.

Last year, El Paso and Juárez had their hottest summer on record. For a month and a half, the temperatures reached triple digits. There was a month’s worth of days where the high reached at least 105 degrees. It was so hot, heat-related emergencies tripled from the previous year.

In the middle of those long days, I felt like the heat would never end. The swamp coolers that were once enough to make it tolerable couldn’t keep up. Authorities told residents to stay indoors and away from the sun. Too much time beneath those hot rays and you start to see things that aren’t there. I started to wonder if, despite its lonesome beauty, the desert was cursed to never feel autumn, winter, or even spring again. Just heat. The type we all want to escape from.

But now it’s December, and the heat’s gone. And even though this has also been the warmest autumn on record, it’s cooled enough that I’m wearing a jacket while standing near the few remnants of Magic Landing.

By the access road, around mile marker 36, two weathered steel posts hold an empty and faded red-and-white checkerboard frame that once displayed a welcome sign. Today, with everything that’s grown around it, it’s easy to miss. Magic Landing did its job of helping the city grow, if not economically then at least geographically. Out here, it doesn’t feel like an endless desert anymore.

There are hotels, restaurants, and stores. Across the highway, an Amazon distribution center is now the city’s largest industrial building. When the mayor announced its construction in 2020, he said it was a symbol of El Paso’s bright future. Six months later, construction paused after workers uncovered a human bone buried beneath the dirt.

About 2 miles east, still on I-10, lies the most tangible reminder of the failed park. In front of a building that sells furniture and home decorations sits the steam-engine train that once circled the park atop a 14-foot-high ledge. Touching that train, which hasn’t run in decades, is the closest I’ve come to Magic Landing. Until recently, it hadn’t dawned on me that when I first saw and heard those commercials as a boy, they were advertising a place that was already dying.

I haven’t stopped thinking about what Magic Landing was supposed to be, what it became, and the distance between those two points. I haven’t stopped thinking about how, for better or worse, the desert inspires us to see things that don’t exist.

Magic Landing never reopened after 1988. For almost a quarter-century, the park rusted and wasted and burned away in the desert. Small pieces of it scattered like ash during March and April’s violent winds. Then during the summer, the vicious sun and heat further beat it down, like everyone and everything here. It slowly disintegrated until those who built it razed it completely. Like a mirage, it vanished.

But sometimes I close my eyes and I can see it.

Roberto José Andrade Franco’s Open Road essay “The Desert Reclaims Everything” appeared in the November 2020 issue and was nominated for a National Magazine Award.