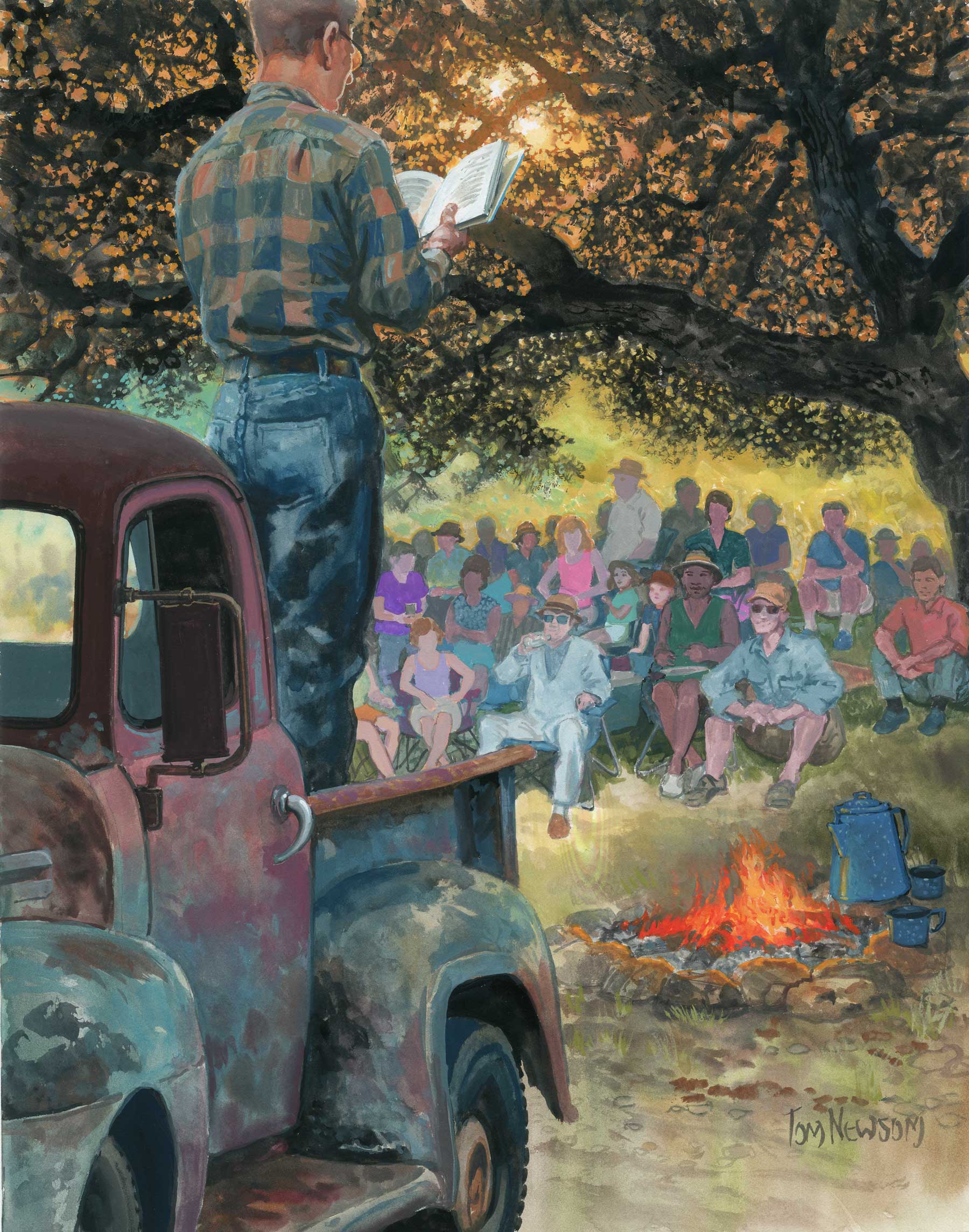

Dobie had been dead more than 50 years, but I’d just put together a new book of his best writing, The Essential J. Frank Dobie (October 2019, Texas A&M University Press). Now I was invited to join some of the state’s leading writers and storytellers at this festive literary gathering known as “Dobie Dichos,” Spanish for “sayings of Dobie.” Over the past decade, I’ve become a regular here, joining people from all over the state who travel to the historic village of Oakville (pop. 30). Everyone gathers under a majestic live oak tree beside an old stone jail and eats chili con carne with pan de campo. Then, as the sun sets, we pay homage to Dobie, who grew up on a nearby ranch in the surrounding brush country, by reading his works.

Born in 1888, Dobie came of age just as old pastoral lifeways were crumbling before the rapidly expanding industrial age. In the 1920s, after serving in World War I, he became an English instructor at the University of Texas in Austin. Dobie taught British literature, for American writing was dismissed as unworthy of study.

As for Texas, well, we were known for cattle, not books. Still, Dobie understood that our state had a proud oral-storytelling tradition. He had grown up hearing real-life accounts of the frontier days, of epic quests for lost mines and buried treasures. He learned of renegade Longhorns that busted out of northern stockyards and traveled 800 miles to return home. Dobie knew vaqueros who’d encountered ghosts every bit as real as Hamlet’s father, and he heard accounts of trickster coyotes that rivaled anything the Brothers Grimm had compiled.

Dobie feared that, while he was busy teaching young Texans about British literary fashions, much of their own cultural inheritance, which had never been written down, was in danger of disappearing forever. He decided to go out and collect these stories from surviving old-timers. He adapted the tales he heard into best-selling books and thus, Texas literature was born.

It was a long journey for me to appreciate Dobie, who died in 1964. I’d grown up in the backwash of the ’60s and was raised in the Dallas suburb of Mesquite. I was dimly aware of a Texas mystique, but the only world I knew was tract homes and chain stores, bordered by interlocking expressways. Like other school kids, I dutifully regurgitated the gospel taught in our Texas history classes, but I had little sense of what it really meant to be a Texan, or what made this place so special. That process would take many years, and it would require a lot of help from Dobie.

As I stood on the old truck at Dobie Dichos, I felt welcomed here as a paisano, Spanish for “fellow countryman,” a term Dobie favored. Above all else, Dobie wanted to educate Texans about their surroundings. He said, “It seems to me that other people living in the Southwest will lead fuller and richer lives if they become aware of what it holds.”

The mesquite logs crackled in the fire, and I thought of my old hometown. As a kid, I only knew mesquites as brushy trees no one much liked. It wasn’t until reading Dobie that I came to understand their greater significance.

“The mesquite seems to me the most characteristic tree or brush that we have in the Southwest,” Dobie wrote. “Its name comes to us from the Aztec, and its association with the land and the peoples’ of this region is dateless. The mesquite is as native as rattlesnakes and mockingbirds, as distinctive as northers, and as blended into the life of the land as cornbread and tortillas. Humans and other animals have been making use of it for untold generations; they are still making use of it.”

As for Texas, we were known for cattle, not books. Still, Dobie understood that our state had a proud oral-storytelling tradition. He adapted these tales into books and thus, Texas literature was born.

Who knew that mesquite was an Aztec word? Or that it was so closely intertwined with human history? Dobie explained that Native Americans relied on mesquite bean pods as a food staple, that the long thorns served as pins, and that the tree’s amber-colored sap was used as a glue by Apaches to make woven baskets watertight.

He described how the beans, leaves, roots, and bark were brewed into teas or made into lotions to treat everything from headaches and flesh wounds to colic and dysentery. He told how Comanches favored mesquite fires because they gave off relatively little smoke, and he noted that when a frontier Texan named Big Foot Wallace “wanted to describe eyes as being especially bright, he said they ‘glowed like mesquite coals.’”

Dobie had taken the commonplace object behind my ordinary suburb and injected it with life, with meaning. In this and so many other ways, Dobie can make the world around us come alive. He makes us all paisanos.

My appreciation for Dobie crystallized while working as a curator at The Wittliff Collections, a magnificent archival repository at Texas State University devoted to the writers, photographers, and musicians of Texas and the Southwest. Bill Wittliff, the recently deceased author and photographer who adapted Larry McMurtry’s novel Lonesome Dove for TV, founded The Wittliff with a gift of Dobie’s papers to the university.

Earlier, as a graduate student studying Southwestern literature, I had learned a bit about Dobie. I delighted in his famous observation: “The average Ph.D. thesis is nothing but a transference of bones from one graveyard to another.” But beyond that he didn’t come off very well.

I read devastating critiques of his writing by some of my literary heroes, including McMurtry, who judged Dobie’s prose to be “endlessly repetitious, thematically empty, structureless, and carelessly written.” Even worse, I heard him condemned as a racist and saw him dismissed as a sexist, though without much evidence.

Then one day at The Wittliff, I began exploring his archive for a planned exhibition. What I discovered blew my mind. Dobie single-handedly integrated the Texas Folklore Society in the 1920s—with a woman. One of the young writers he mentored, Jovita González, became president of the Folklore Society in 1930. This was an astonishing accomplishment for a Mexican American woman in Texas during those years.

It turns out Dobie opened doors for many other accomplished people. In 1934, he invited J. Mason Brewer, an African American, into the Folklore Society. By the ’40s, Dobie was one of the most prominent white Texans to champion civil rights. He publicly called for integrating the University of Texas, which led in part to the university firing him.

I began to see that Dobie was also a visionary environmentalist. He helped inspire Big Bend National Park by galvanizing the Texas Legislature to preserve the vanishing wilderness. He also was instrumental in the movement to save animals from extinction by railing against the widespread use of chemical poisons such as DDT.

Believing that “Texas needs brains,” Dobie constantly fought for the promotion of the intellect. He waged the battle against censoring school textbooks. He was the first public figure in Texas to stand up against McCarthyism. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI investigated him, Lyndon Johnson’s White House celebrated him, and ultimately, he was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom just four days before he died.

I was amazed. Who knew that Dobie was such a renaissance man?

But hardly anybody was aware of this stuff. The last biography had been done 30 years earlier and was sorely out of date. I knew I could do something fresh if I avoided the literary analysis and focused on Dobie the person. So, I deliberately concentrated only on his writings that revealed useful biographical data. In 2009, I published J. Frank Dobie: A Liberated Mind, which tells the story of how Dobie grew up in a prejudiced time but transformed himself into one of the state’s leading champions of civil rights and intellectual freedom.

This year’s Dobie Dichos takes place in Oakville on Nov. 1. Participants include writers Sarah Bird and Sergio Troncoso, plus musician Tish Hinojosa.

For more information and to purchase tickets, visit dobiedichos.com.

A couple of years later, I got invited to that South Texas ghost town, where I found Dobie’s voice coming alive at my first Dobie Dichos in a way I had never heard before. My work with him was apparently not done.

The village of Oakville sits along a cluster of hills crowned with live oaks on the north side of the Nueces River. Located halfway between San Antonio and Corpus Christi, this had been the bustling seat of Live Oak County in 1888, when Dobie was born, but then the railroad veered 10 miles south to George West. Soon, the courthouse followed, and Oakville sank into oblivion.

In recent years, Oakville’s old town square has been lovingly restored, making this an attractive stop for visitors traveling along Interstate 37. The plaza is anchored by the stone jail, an impressive Italianate-style structure built in 1887 of rough-hewn sandstone blocks. Today, the renovated jail is a picturesque B&B. Other vintage buildings in the area have been saved, from the post office to the mercantile store, and moved to the tree-shaded plaza. This has recreated an atmosphere Oakville hasn’t seen in nearly a hundred years, making it a destination for weddings and family reunions.

In 2011, San Antonio-based writer William Jack Sibley decided to create a literary festival honoring J. Frank Dobie. Sibley, like Dobie before him, comes from a ranching family in the areas surrounding Live Oak County. A wiry bullwhip of a man with a crackling wit, Sibley can rope and deworm cattle with the best of them. He is also an accomplished author whose literary output includes stage plays, screenplays, and two acclaimed novels set in Texas.

“I grew up reading Dobie,” Sibley told me. “What made it so fascinating is that his stories didn’t take place in some far-away fantasyland. They happened in places I knew.”

Sibley worked with local folks to use Oakville as a venue for staging Dobie Dichos. He had a bold vision for recruiting performers. “I decided to go for broke and invite the best, most prestigious writers I could think of,” he said. “I wasn’t sure what to expect, but to my surprise, they all said ‘yes.’”

There is a lot of love and respect for Dobie among the Texas literati. Writers recognize his historical importance and more than a few have drawn inspiration—and helpful research—from his work. And some, honestly, just like the idea of coming out to a cool literary event in an old ghost town.

The roster of performers who have participated at a Dobie Dichos event reads like a Hall of Fame of Texas letters: Stephen Harrigan, Paulette Jiles, Elizabeth Crook, John Phillip Santos, Carmen Tafolla, Bill Wittliff, Naomi Shihab Nye, and many other luminaries.

I missed the first year of Dobie Dichos, but in 2012 Sibley invited me, on the strength of J. Frank Dobie: A Liberated Mind, to speak in the capacity of Dobie’s biographer. This was the first of several iterations of Dobie Dichos in which I have participated. On the appointed evening, I drove the leisurely back roads to Oakville and I arrived at the old town square by late afternoon.

I strolled among the renovated buildings and admired the antiques on display. A band performed old Western swing tunes while everyone lined up for food and iced-down beer. Under the massive live oak next to the old stone jail, The Twig Book Shop, based in San Antonio, set up tables with books by the featured authors, along with Dobie’s titles. Some folks brought their kids and a couple of friendly dogs wandered about. Everyone seemed to fit right in.

As night fell, the communal campfire blazed inside a stone pit, carrying the aroma of mesquite. If anything could summon Dobie’s spirit back to Live Oak County, I thought, this would do it. “Often I get homesick for the smell of burning mesquite wood,” Dobie once observed. “Nothing seems remote to the light and the warmth of the fire.” Beyond the softly lit plaza and flickering flames, I could hear the occasional yip of a coyote, Dobie’s favorite animal, out roaming somewhere in the darkness.

Then the show began. I thought I knew Dobie, but I was completely unprepared for the power of these live readings. I’d only read him on the page. Now, for the first time, I was hearing his stories as they were meant to be shared—out loud, under the open skies, with a campfire crackling. The event was a revelation to me. Dobie’s writing sounded great, and so many other people were enjoying hearing it. I began to realize that I had underestimated his gifts as a writer.

When the next autumn rolled around, in 2013, I felt the pull of Dobie Dichos and returned to Oakville, this time as an audience member. I’ve been coming back every year since, paying close attention to how the writers and storytellers have carefully curated their selections of Dobie’s material to great effect. Sitting in my lawn chair underneath the twisting limbs of a centuries-old live oak, warmed by the mesquite fire, and listening to Dobie’s words, a spark lit inside of me.

Inspired by what I was hearing, a new idea began to form. Was there a way to recover Dobie’s purest, strongest voice—the voice these writers and storytellers were sharing to delighted crowds every year at Dobie Dichos?

And then it hit me: What if I went back through Dobie’s writings, this time with an eye toward selecting his most vital and enduring pieces? Then I could judiciously edit those works—pruning away the brushy overgrowth at the heart of criticism by the likes of McMurtry—so modern readers could more easily stay on the narrative trail. I could collect all of them into a new book that specifically honored Dobie’s literary legacy.

I plunged back into reading Dobie and found a once-lost mine, a rich vein of literary ore. I could see, at long last, that Dobie wasn’t just a dusty old writer; he was a timeless writer. He wrote at a moment in history when rapid technological changes were upending people’s lives, when the natural world seemed to be under attack from all sides. Dobie eloquently confronts those critical issues head on, but he also helps us better appreciate what makes this place we call Texas so special.

When I finished putting together my new book, Sibley invited me back to Dobie Dichos, as a presenter, to give everyone a sneak preview. That’s how I found myself stepping up onto the back of that pickup truck last fall.

I looked out at the audience and made my confession. “It took me a long time to figure out that J. Frank Dobie could be a brilliant writer,” I said. Then I began reading from my edited version of part of Dobie’s book Voice of the Coyote. By the time I got to the line, “I confess to a sympathy for the coyote that has grown until it lives in the deepest part of my nature,” you could hear Dobie’s words taking over, casting a spell of their own as they floated on the evening breeze.

Dobie once observed, “Great literature transcends its native land, but none that I know of ignores its soil.” Here on our state’s soil, a new generation is reawakening to Dobie’s enduring contributions to Texas literature.