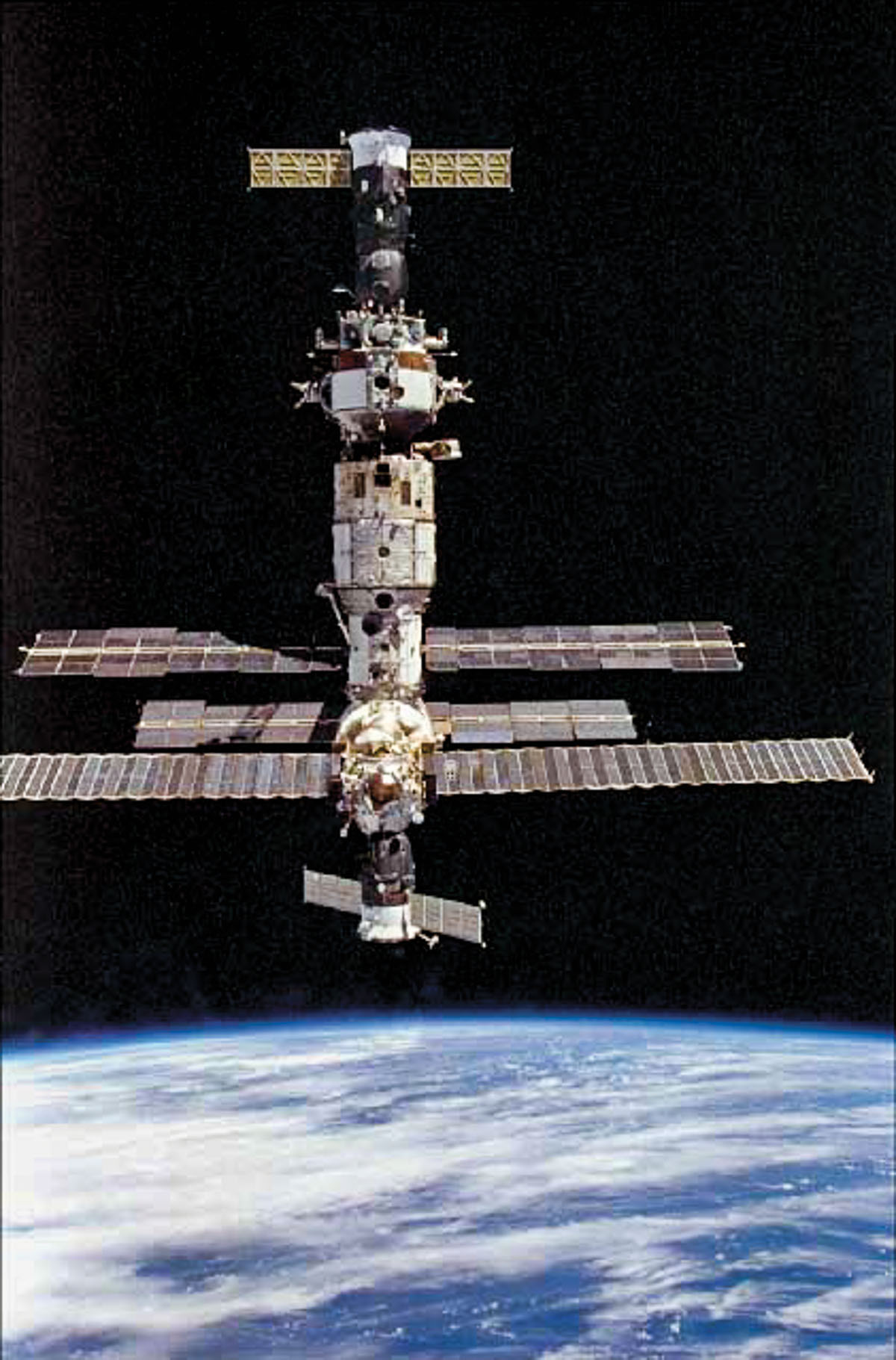

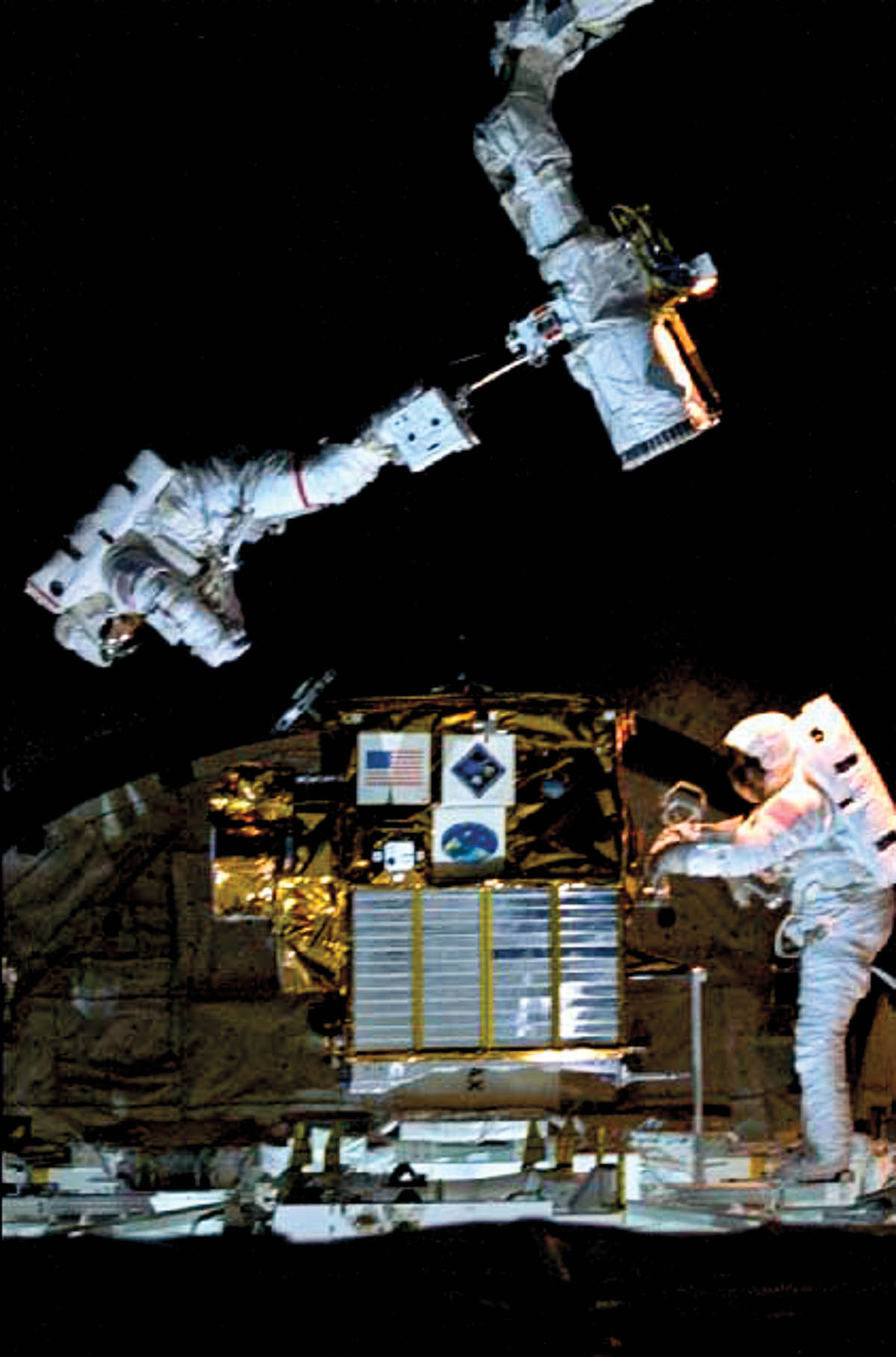

Bernard Harris Jr. in 2020, 25 years after walking in space; a scenic view of Mir during Mission STS-63. Photo by Nathan Lindstrom (left), courtesy NASA (right).

One

giant

leap

of

faith

On the 25th

anniversary

of NASA Mission

STS-63, astronaut

Bernard Harris Jr.

reflects on his

pioneering journey

to become the first

African American

to walk in space

By Michael Hurd

Bernard Harris Jr. in 2020, 25 years after walking in space; a scenic view of Mir during Mission STS-63. Photo by Nathan Lindstrom (left), courtesy NASA (right).

Two hundred-thirteen nautical miles above the earth, Bernard Harris Jr. had an unobstructed celestial view as he floated out of the Space Shuttle Discovery hatch and into history.

But his noticeable pause “for a little bit,” as he recalled, prompted NASA’s Mission Control to ask, “Why are you doing that?”

Harris was marveling at his surroundings, as space shuttle Discovery orbited at a dizzying 17,000 miles an hour, circling Earth once every 90 minutes. He gathered himself and quickly responded, “Oh, nothing.”

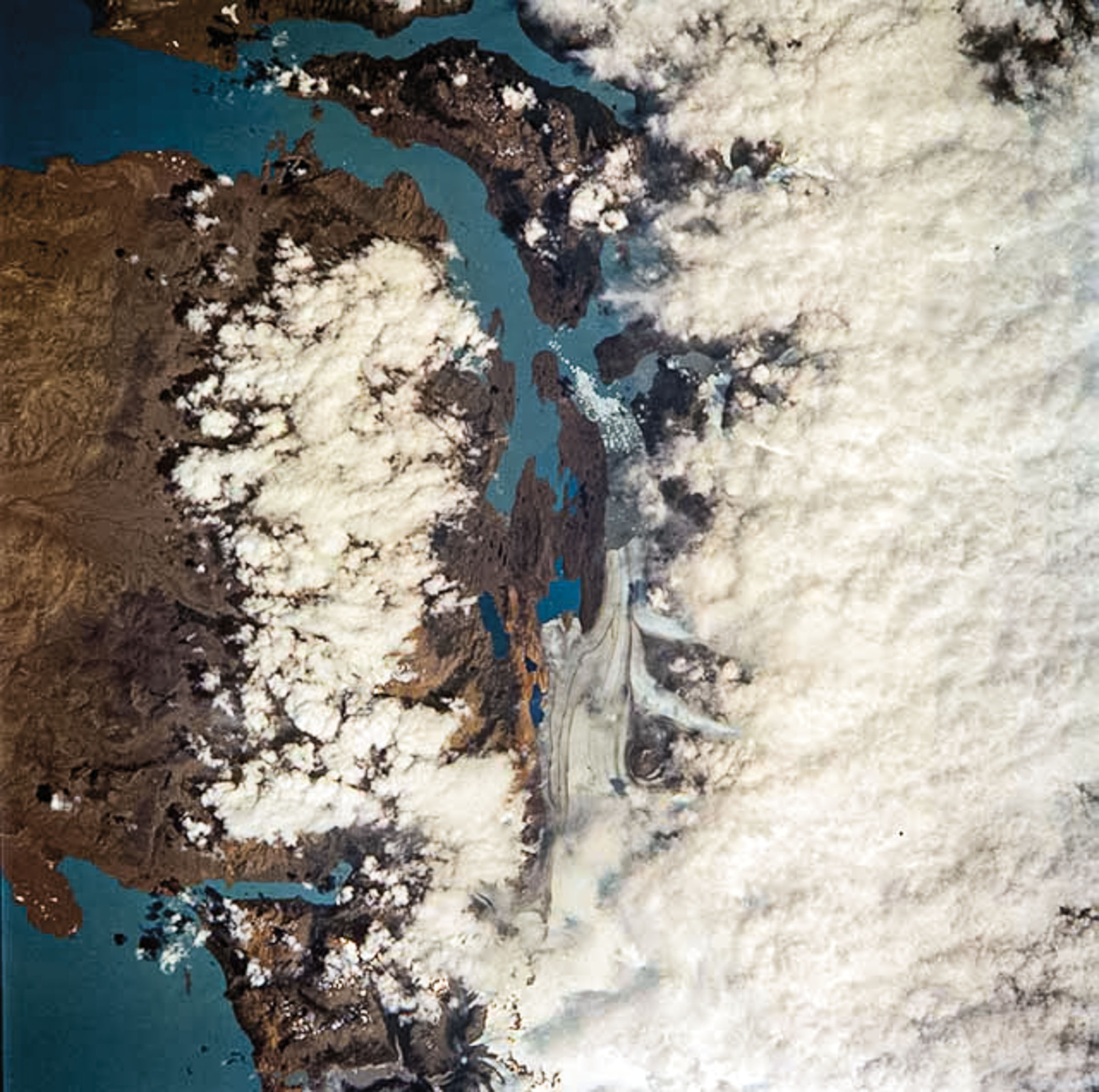

Looking down on mountains and a lake during STS-63. Photo courtesy NASA.

But the unfolding event was very much something. Mission STS-63, which launched Feb. 3, 1995, broke ground in many ways. It marked the first rendezvous of the American space shuttle with Russia’s space station Mir. Also on board, Eileen Collins, an American, became the first woman to pilot a space shuttle, and C. Michael Foale became the first British-born American astronaut to walk in space. And for payload commander Harris, who was on his second and final NASA mission, it was the improbable realization of a childhood dream, as he became the first African American to walk in space on Feb. 9, 1995.

“The little boy who was forced to use the back door of a [Waco] diner in the sixties because of his race had triumphed in the nineties,” he wrote in his 2010 memoir, Dream Walker. “It was my day and I was flying pretty high!”

Harris, born in Temple in 1956 and now based in Houston, grew up a big fan of all things science fiction, from Buck Rogers to Star Trek. The 1969 Apollo 11 spectacle was must-see TV for Harris, though a continuing social drama hovered in the background as Black Americans fought hard for civil rights. They marched, protested, sat in, and rioted—Burn, baby, burn!—for most of the decade that neared its end with Neil Armstrong

setting foot on the moon. The watershed moment fully captured the world’s imagination and instantly cemented the career aspirations of 13-year-old Harris, despite the racial unrest he saw on TV and in his everyday life.

“I could see human beings accomplishing one of the greatest feats in the world, but I could change the channel and see our people being disgraced, dogs sicced on them, water cannons spraying them,” Harris recalled in a 2019 Houston Public Media interview. “To decide, despite what I saw, that I wanted to be an astronaut, was a big leap of faith.”

When I interviewed Harris earlier this year, he described his innate drive to succeed “in spite of the segregated and hostile racial climate of the ’60s” as an inherited family trait. His mother, Gussie Harris, bolstered his dreams by insisting he could be whatever he wanted, no matter that he grew up poor.

Harris’ family moved to Houston shortly after he was born. They lived there until he was 6, when Gussie and Bernard Harris Sr. divorced and Gussie took her three children back to Temple. She had a home economics degree from Prairie View A&M University and a desire to teach, but no local teaching offers came in. So, she uprooted the family and drove more than 1,000 miles to Greasewood, Arizona, to teach at a boarding school on the Navajo Nation Reservation. During the summers, the family would retreat to Texas, where Gussie met and married Joe Burgess, a police officer. Harris said his new father figure helped bring stability to a family set on accomplishing goals.

“There are certain characteristics you’re born with, and mine was wanting to do things that people hadn’t done before,” Harris explained. “Once I had it in my mind that I wanted to go into space, I was not going to be deterred. Looking at television and seeing the box they were trying to paint us in as African Americans, I was saying, ‘It’s not going to happen here. That’s not going to determine my dream.’”

Harris’ experience growing up in the Heights neighborhood near downtown Houston, where “not a lot of kids made it out,” proved critical to his character development. It instilled in him a determination to give back to the Black community, especially kids searching for hope. Because Harris’ biggest obstacle to realizing his space dreams was his race, he now works to help minority kids obtain STEM educations as CEO of the National Math and Science Initiative.

The Dallas-based organization operates programs designed to boost the number of STEM teachers, increase student access to Advanced Placement courses, and train existing teachers. Against the backdrop of the national dialogue on racial injustice, Harris spends most of his day now conversing with educational leaders and corporate executives who want to know how they can make the system more inclusive.

“I see this as an opportunity for those who didn’t believe that systemic racism exists to see that it’s been a black and white issue for a long time,” Harris said. “Now it’s in full color in their faces, and they see the issues that minorities have dealt with for all these years, particularly in the Black community. It’s raised the awareness, and people are reacting in a positive way, saying, ‘We’ve got to change.’”

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” President John F. Kennedy said in a speech at Houston’s Rice University on Sept. 12, 1962.

Mir as viewed from the Space Shuttle Discovery. Photo courtesy NASA.

Seven years after Kennedy’s imperative words pushing for a manned lunar landing, Harris sat rapt as one of the most important moments in all of history played out on his family’s small black and white TV screen in Tohatchi, New Mexico, where they’d moved in 1967. Armstrong walking on the moon instantly inspired a young Harris, though he did not yet know the astronaut corps and NASA in general were all-white fraternities.

In 1961, Alan Shepard was the first American to travel into space. It would be 22 years before Guion Bluford would become the first African American astronaut to travel into space. Bluford was a member of STS-8, the third Space Shuttle Challenger mission, which conducted the first night launch and night landing. In between Armstrong’s and Bluford’s missions, Black community leaders—especially in Houston, where the Johnson Space Center is located—pushed NASA to hire astronauts of color.

As a young Harris came to understand NASA’s lack of diversity, he rarely mentioned his goal in public.

“Early on in the program in the ’60s, we were, as African Americans, fighting just for the right to vote and to be included,” Harris recalled. “So, the idea of sharing my dream meant having people tell you, ‘There are no Blacks at NASA. What makes you think you can become an astronaut?’ So, I held it closely to the chest.”

That is until he attended the University of Houston, where his Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity brothers could see the stars in his eyes. His close friend Gerald McElvy, now a regent with the University of Houston System and former president of the ExxonMobil Foundation, described what they saw in the future spaceman.

“He was very impressive and carried himself well,” McElvy said. “He had very high aspirations, as did I, and we’d talk about doing something significant together in the future, though we didn’t define it or know what it was. He distinguished himself as one of the more intellectual members of the group and at times would say something that flew over everybody’s head. And one time someone said, ‘Would you beam me up, Scotty?’”

Armstrong walking on the moon instantly inspired a young Harris, though he did not yet know the astronaut corps and NASA in general were all-white fraternities.

Following the University of Houston and Texas Tech Medical School, Harris got his first big break during a residency in internal medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. His first rotation was in rheumatology with Dr. Joseph Combs, who mentioned the clinic had created the field of aerospace medicine for the early space program. An eager Harris shared his NASA aspirations, and Combs introduced him to the head of the Aerospace Medicine program.

“I didn’t know there was an Aerospace Medicine department there,” Harris said. “This is why I always think that God takes care of you. I have this saying: ‘If you hold something in your heart deep enough, the universe conspires to make those things happen.’ This was one of those things.”

Combs was one of many mentors for Harris along his arduous journey, but he credits Dr. Joe Kerwin as the one who paved his path to space. In 1973, Kerwin became the first American physician to work aboard Skylab, the first U.S. space station. There, Kerwin made the first medical observations about humans living in a microgravity environment.

“I saw that as an avenue for me to go to space,” Harris said. “If I could become a physician, that would give me the credentials to do research at NASA, and eventually, if the stars aligned, I would be able to become an astronaut.”

Harris chose bone research as his endocrinology specialty, which became his ticket into the astronaut program.

In August 1990, Harris began a year of training and evaluation with 22 classmates at Johnson Space Center. Upon completion of the program, he was prepared to wait several months, perhaps years, before his first assignment. But three weeks later, he was selected first in his class for a mission. On STS-55 Columbia, he performed experiments in the multinational Spacelab. The launch, which included an international crew, would be aborted twice before the successful attempt on April 26, 1993. By then, Harris’ emotions had leveled off from the range he’d experienced during the first attempt on March 22.

“On the appointed day,” Harris wrote of the first attempt in Dream Walker, “I found myself strapped in tightly 150 feet above the ground along with my six fellow travelers, all of us sitting on top of enough rocket fuel to lift 5 million pounds into Earth’s orbit. One side of my brain was thinking, ‘This is great. I’m going to launch into space today,’ and the other side was thinking, ‘What in the world am I doing here?’”

Over his 10 years of service, Harris logged more than 438 hours and 7.2 million miles in space, and developed in-flight medical devices to extend astronauts’ stays in space. His work in medical telemetry—measuring and transmitting data—would be his focus once he retired from NASA in 1996. He started Vesalius Ventures in June 2002 and serves as CEO and managing partner of the venture capital firm that supports and invests in early- to mid-stage healthcare technologies.

His extraterrestrial mission had ended, but his “terrestrial” mission, as he calls it, had just begun: lifting kids through education. In the mid-’90s, Harris partnered with McElvy, as the two had planned back in college. Their youthful dream manifested in a science camp for minority kids in grades six through eight.

“I’m providing hope for them, and I believe one of the important solutions to address the social injustice in this country is education,” Harris said. “We have not had the same level of socioeconomic prosperity in this country, and the way that can change, in particular for people of color, is through education.”

The ExxonMobil Bernard Harris Summer Science Camp, held at more than 50 colleges and universities across the country, has become a huge success. It quickly spread from 10 camps in 2005 to 30 camps by its third year. And Harris is the face of the effort.

“Bernard visited every one of those camps, from Washington and Massachusetts to Texas and Alaska,” McElvy boasted. “His appearing at those camps was exactly what those kids needed to see: people who looked just like them, who had actually flown in space.”

More than 2 million kids have gone through his National Math and Science Initiative programs. The organization’s educator training and materials are centered on racial equality and access, with support from the United Negro College Fund.

“The camps gave me a place to see how important it is, especially for students of color who don’t have role models readily available to them and don’t see themselves reflected in STEM, to bring these types of opportunities to them,” said Mariam Manuel, a professor at the University of Houston and former curriculum coordinator and instructor for the camp.

The kids remind Harris of himself at 13. He tells them his story and declares that if a poor kid like him can make it, so can they.

Each time he tells his story, he sees a familiar spark in their eyes—the gleam of inquisitive dreamers determined to take their own giant leaps.

“I have this saying: ‘If you hold something in your heart deep enough, the universe conspires to make those things happen.’”

We Have Liftoff

Space Center Houston, the official visitor center of NASA’s Johnson Space Center, reopened in July after a temporary closure due to COVID-19. Masks and social distancing are required, and visitors can review the center’s “Know Before You Go Guide” on its website for other tips on how to plan a visit and purchase timed admission tickets. New exhibits include:

› The SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, the first rocket to be reused for a NASA supply mission to the International Space Station.

› The Apollo 13: Failure is Not an Option exhibit summarizes the “Houston, we’ve had a problem” mission.

› The Mission Exploration experience details the specific roles of astronauts, science officers, engineers, and flight controllers.

› Mission: Control the Spread explores how crisis sparks innovation, and details NASA’s role in helping with the COVID-19 response.

Space Center Houston

1601 E. NASA Parkway, Houston.

281-244-2100; spacecenter.org