The cowboy rides in from the West,

mulling stanzas, lines and words.

Winter delivers a fleeting rest

from the fences, trenches and herds.

Humble and independent in nature,

his friends are the horse and hawk,

But this trip is for a matter of culture,

to honor a special kind of talk.

Suspicious of the city and its business,

the cowboy girds himself for the crowd.

He wants to give personal witness,

to share his life with the world out loud.

The cowboys on Alpine descend,

the West Texas wind blowing and swirling.

They speak and they sing and they listen

at the Texas Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

Forgive my hackneyed introductory poem, but it can be hard to shake the poetic lens from your perspective after attending the Texas Cowboy Poetry Gathering. The mythic American cowboy looms large among the arid ranches, vast skies, and open highways of West Texas. And at the annual gathering in Alpine, which takes place annually in February, the poets make no bones about their love for the legendary cowboy life and the homespun traditions of today’s ranching families.

I made my way out west last February for the annual gathering and found a welcoming group with a sincere dedication and diversity of approaches to their craft. While it sometimes felt like I had stumbled upon a cattle auction or a casting call for a Hollywood Western, the overarching themes of the weekend resonated universally, focusing on topics like independence, adversity, religion, the environment, animals, personal foibles, and humor. Above all, the poets and their candor were uniquely entertaining, whether delivered in clever rhyme, pensive free verse, or old-time song.

To get in the spirit of the gathering, it’s best to rise early, brave the chill, and head to the chuck-wagon breakfast at Kokernot Park on Friday and Saturday mornings. More than 200 locals and tourists showed up the morning I attended. With temperatures in the upper 20s, folks huddled around campfires to drink coffee brewed in black kettles and wait for fresh Dutch-oven biscuits that baked in the embers. As the sun emerged, the eastern hills and dormant cottonwoods cast long shadows across the corner of the park dubbed Poet’s Grove.

“You can cook biscuits in your house all you want to, and they’re not going to taste like these biscuits here.”

Richard Bryant, a chuck-wagon cook from The Grove—a community near Temple—stepped out of the kitchen tent to survey the scene. He said the cooks started putting wood on the campfires at 4 a.m. “It’s the old way of doing it,” Bryant said. “You can cook biscuits in your house all you want to, and they’re not going to taste like these biscuits here.” He was right. The biscuits were rustic, crisp, and especially satisfying with the accompanying gravy and scrambled eggs.

After breakfast I made the 1½-mile drive to Sul Ross State University, where the bulk of the Cowboy Poetry Gathering takes place. For two full days, poets and spectators crisscrossed the hillside campus to classrooms, theaters, and conference rooms for 50-minute poetry sessions. There are about 40 sessions per day, with up to 10 taking place at any given time. Most of the sessions feature three performers, and a few offer open-mic opportunities for the crowd. While the sessions have names like “Rope Burns & Rodeo,” “Cowboy Crooners,” and “Livestock Woes,” it doesn’t take long to figure out that the titles are merely suggestions.

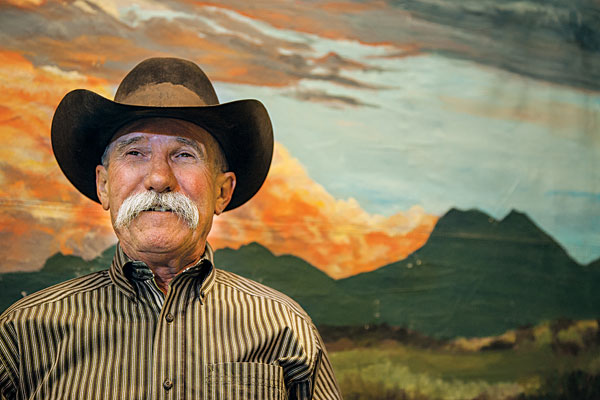

At a session called “Let’s Talk About Poetry,” Alpine-area poet Joel Nelson allowed that he doesn’t care for the term “cowboy poetry.” This was interesting to me because Nelson is among the most respected of the genre. The National Endowment for the Arts awarded Nelson a National Heritage Fellowship in 2009, and his 2000 CD, The Breaker in the Pen, is the only cowboy poetry recording ever nominated for a Grammy Award. Nelson certainly looks the ranching part, with his curtain mustache and weathered felt hat, and he lives the life of a working cowboy and accomplished horse trainer on the nearby Anchor Ranch. I asked him what he meant.

“I feel like by labeling it a particular form of poetry, we might cause people to become disinterested, thinking that it wouldn’t hold anything for them. I think good poetry is good poetry, and we don’t have to label it,” Nelson explained. “I’m such a fan of poetry of any kind, as long as it’s good and well-written, that I like to break out of the box and do other types. Even at this event, we have sessions that are not necessarily rhyme and not necessarily cowboy. I feel like that’s really important, because I don’t think people who have something to say need to be limited by categorization.”

As the sessions unfolded, the performers’ varied interpretations and styles of cowboy poetry became more evident. There was Nelson’s reverent tribute to horses in his poem Equus Caballus, Amy Haul Auker’s sensitive naturalist musings, Baxter Black’s raucous ranching jokes, and the playful old-time instrumental tunes by fiddler Glenn Moreland and one-string-bassist Washtub Jerry. A special session featured the voices of a handful of young poets—from shy kindergarteners to eager teenagers—who participated in the gathering’s annual Student Poetry Contest.

The student contest is part of the gathering’s effort to preserve and perpetuate cowboy poetry at a time when the majority of both the performers and the audience is going gray. Outside of the student contest, the weekend featured only a handful of performers under age 50. One of them was Andy Hedges, a 33-year-old from Lubbock. Against a painted backdrop of the Davis Mountains, Hedges’ performance in a Sul Ross seminar room ranged from Curly Fletcher’s classic “The Wild Buckaroo” to the Bob Dylan song “Girl From the North Country” and the Dylan version of the traditional “West Texas Blues.”

Hedges exemplified the prevalence of music throughout the weekend. The first collectors of cowboy song and poem, such as John Lomax in the early 1900s, suggest that the two forms have been linked since cowhands started reciting to one another around campfires and barrooms. “A lot of cowboy songs started out as poems, and a lot of them may have started out as songs, and yet somebody would recite them,” Hedges explained. “Going back to the trail-driving days, when those guys started writing poems and reciting poems and also singing songs, it was very much interchangeable.”

As one of the younger performers at the gathering, Hedges was realistic about cowboy poetry’s appeal to a younger audience. “I think the whole point of this kind of music is that it is old-timey and it is traditional,” he said. “It’s not for everybody. The point isn’t to attract a huge crowd or a crowd of a certain age, but to do this certain kind of art, and do it well. The popularity will come and go.”

Hedges’ comments echoed a recurring sentiment that I encountered among participants at the Texas Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Don Cadden, the president of the gathering’s organizing committee, said the goal of the nonprofit event is to maintain a non-commercial gathering that features poets and singers who, at least mostly, come from the agricultural community and are not professional entertainers. Local businesses and residents sponsor the various performers by paying for their travel and lodging.

“The main purpose of the event is clear-cut: It’s to carry on the oral tradition of the spoken word of the West in poetry, storytelling, and music,” Cadden said. “Our biggest aspiration is to keep it like it is.”