Cresting the Wave

A surfer comes to grips with a dark family secret born from the swells near Bob Hall Pier

by Joe Hagan

When the first nuclear bomb in Nevada was detonated in 1951, my grandfather stood in the desert in Army fatigues. He wore goggles to protect his eyes and snapped a photograph of the mushroom cloud. In high school I found that photo in a box of slides, lifting it to the light in awe.

We called him Poppy, but my mom and her sisters called him the Old Bastard. He wore a flattop and an olive-khaki leisure suit, and he smoked a pipe. In 1957, Poppy moved to Corpus Christi with his second wife, Madeline—my grandmother—an aspiring actress from a well-off family in Connecticut. They had met in Georgia while they were both married to other people. They opened a lumberyard in the Flour Bluff area of Corpus, and Poppy helped raise Madeline’s three daughters.

Four years into the new marriage, Poppy developed both colon and testicular cancer, a gift from the nuclear radiation. The surgery made him impotent. He and Madeline became full-blown alcoholics, fighting bitterly. Poppy beat Madeline with a riding crop. Their older daughters, Mary Lou and Lynn, got married and escaped. That left my mom—a tomboy with funny teeth who rarely wore shoes and loved the Beatles—to live with two dysfunctional drunks. She met my father at a raucous party in Flour Bluff. He was enlisted in the Navy and stationed at the local air base. A skinny, red-haired kid from North Carolina, a year out of high school, he drove a 1965 Mustang and kept a Donald Takayama surfboard on the roof to impress girls at the local surf spot on Padre Island, Bob Hall Pier.

In 1969, when my parents first began dating, they’d walk to the end of Bob Hall Pier to catch the sunset, a first glimpse of life’s horizons. They watched phosphorescence sparkle in the crashing waves. Built in 1950 and named after local commissioner Robert Reid Hall, the pier had been destroyed by hurricanes in 1961 and 1967 but was rebuilt. Postcards advertised it as a tourist attraction: 1,200 feet of walkway and a pavilion that rented fishing poles for a dollar. It even lit up at night. Though the surfing was excellent during hurricane season, the pier was mainly a place for young people to park on the sand and drink beer. When my dad’s surfboard was stolen off his car in front of Poppy’s house on Dolphin Street, he never replaced it.

Surfing, however, was destined to return to his life—when I took it up as a teenager. And as it turned out, the secrets of my own story, as a child of the Gulf Coast, were hiding in those waves off Bob Hall Pier. But it would take years before I understood them.

A month into my parents’ courtship, my mom found her mother dead in the bedroom, asphyxiated on her own vomit. She ran out of the house screaming and collapsed on the lawn. Poppy started drinking more heavily, staring at Madeline’s portrait while listening to the theme song from Doctor Zhivago.

My dad was moonlighting at Poppy’s lumberyard when Hurricane Celia destroyed swaths of Corpus Christi in August 1970. (Bob Hall Pier, miraculously, was spared.) Poppy and my dad were boarding up the lumberyard when the winds came whipping in. That was the week I was conceived. When my mom found out she was pregnant, she left it to my dad to deliver the news to Poppy. Outweighing him by 100 pounds or more, Poppy threw my dad against a wall and threatened to jab his eyes out.

At 19, my mom was at sea. Unprepared for motherhood or marriage, she fled to her sister Mary Lou’s house and stopped taking my dad’s calls. A doctor suggested she have an abortion. Instead, it was decided she’d fly to Rhode Island to live with her sister Lynn and Lynn’s husband, Big Dave, who was also in the Navy, stationed at Quonset Point. My mom would have the baby in a military hospital and put the child up for adoption.

On April 30, 1971, the doctor took me from my mother and carried me down the hallway to a foster care ward. Under the law, my mom had 30 days to change her mind. She saw a psychiatrist in downtown Providence, where she began to hear herself think for the first time. Her mother had died. Her stepfather was a drunk. She was an unmarried mother to a child she’d just given up.

Two weeks later, she decided she’d made a terrible mistake and flew back to Texas to patch things up with my dad. They hadn’t seen each other in months. She returned to Rhode Island to retrieve me a week before I was to be adopted. The first time my dad laid eyes on me was at the airport in Corpus Christi. I was six weeks old.

I didn’t learn this story until I called my Aunt Lynn this summer to talk about her memories of Bob Hall Pier. “I never did understand why your daddy felt the need to keep it a secret,” she told me in her familiar twang. My parents, pained and embarrassed by their past, had changed the anniversary of their marriage and lied for decades.

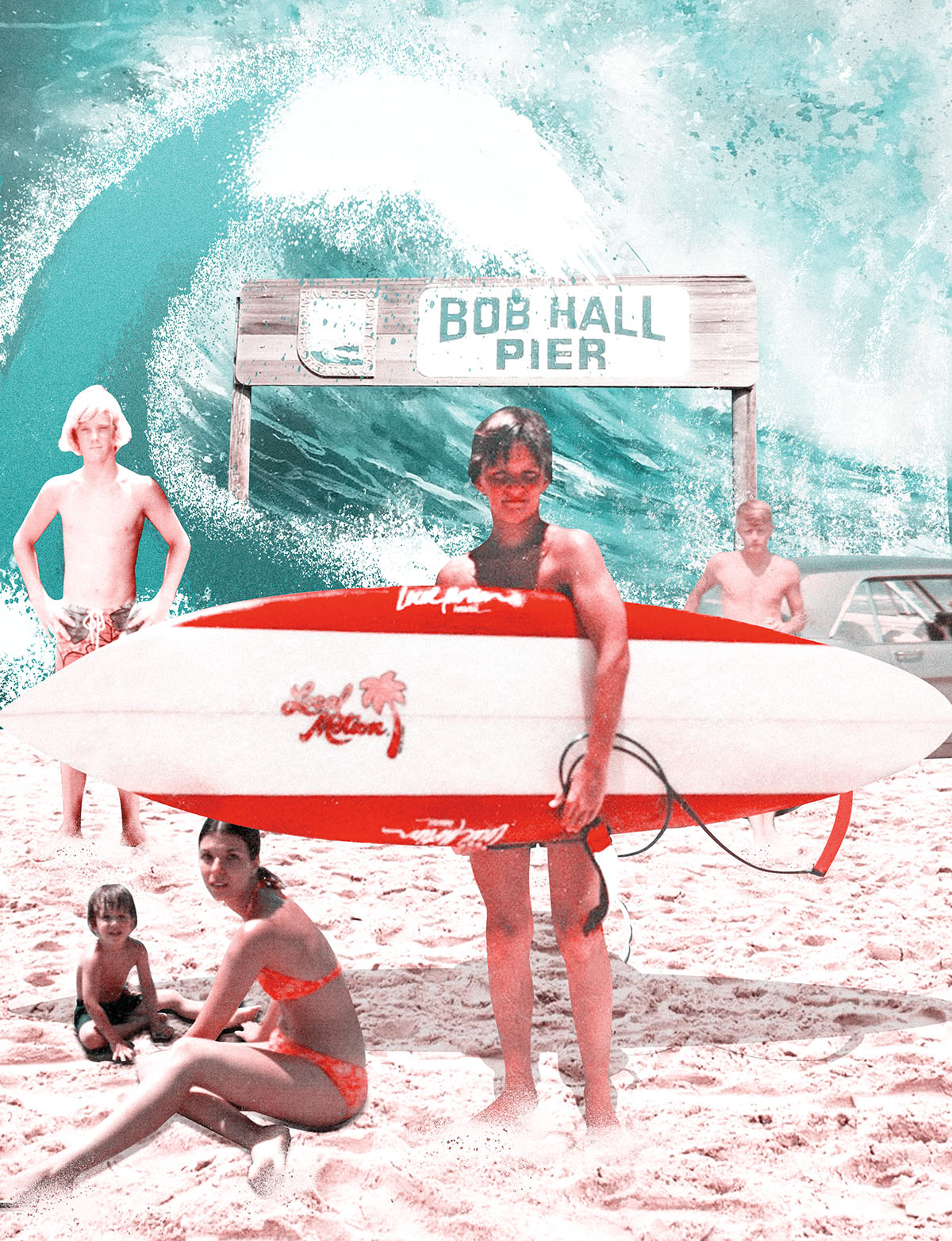

Though I never knew the story, it was always there, sometimes hiding in plain sight. Bob Hall Pier, it seems, was a beacon, a clue. The first time I went there was in 1974, when I was 3 years old. My dad had left the Navy, joined the Coast Guard, and was stationed again at the air base in Flour Bluff. A family snapshot shows me playing on the shore next to my mom, who wears a bikini and a worried look. My dad was struggling to find a career path, and though he eventually became a successful officer, his future at the time looked uncertain.

From my vantage point, life became a series of false starts. Every four years, the Coast Guard would transfer our family to another duty station, and I’d leave a group of friends I’d just begun to know and move to Washington, D.C., or Marietta, Ohio, where I attended antiseptic school buildings that echoed with weird accents and exotic faces.

My mom, no matter where we lived, wore seashell necklaces and kept a jar of sand dollars on a table as evidence of her kinship with the Gulf Coast. As a child, she would tell me we were beach people, though my dad was from Appalachia and, despite stints in the Navy and the Coast Guard, disliked the water. Corpus Christi, Padre Island, and Bob Hall Pier became symbols of my mom’s origins, what passed for a homeland.

When my dad was transferred back to Corpus Christi in 1985, I viewed it as a return, though I had only the vaguest memories of the place. By then I was 14, short and slight, bad at sports, adept at Dungeons & Dragons, and a fan of Billy Joel. In Ohio, I’d become an easy mark for bullies. I began dreaming of a personal reinvention in Texas, determined to show up to ninth grade as somebody else entirely—a guy who belonged somewhere.

My North Star was my cousin, Little David, the son of my Aunt Lynn and Big Dave, who’d since relocated to Corpus Christi. In a family picture from 1974, I’m sitting on my mom’s lap flanked by David and his sister Daphne in my aunt’s backyard, surrounded by grapevines. At 15, David is shirtless, tan and lean in board shorts, an Adonis-like surfer with long blond hair and crystal blue eyes. I have a single memory of the visit: sitting on the floor in David’s bedroom while he plucked “Stairway to Heaven” on an acoustic guitar, a moment that tie-dyed my brain for all time.

By the time I returned to Texas, David was in his mid-20s, a carpenter by day and bartender by night with a rotating cast of girlfriends. He was still a committed surfer. We were in his mom’s backyard in the summer of 1985 when he presented me with a dinged-up, sun-faded Local Motion surfboard from Hawaii. That day my dad took a picture of me next to Bob Hall Pier holding the board under my arm, my bicep artificially bulging against the rail, a picture that pleased me. The magic was already working. As I wrote in a 10th grade English paper about my cousin: “Somehow I thought the mystique of the board would rub off on me.”

I waded into the water and bobbed around awkwardly, taking a few belly rides on white water, coached along by David. It was a start. I watched him paddle out on his gleaming Channel Islands surfboard, aimed for the waves near the pier. He casually feathered in with the bulls of the local surf pack, men who seemed to own the outer swells. The waves, tall and thick, looked frightening to my eyes, but David dropped in on a menacing roller and soared easily down the face as it curled and crashed after him. I was in awe, proud that I was even related to him. He was among the few who could “shoot the pier”—surf a wave directly under the pier to the other side.

When we got home that day, my skin was burned bright red, flayed by the Gulf Coast sun. I lay in bed, barely able to move, cooling like a loaf of bread. Soon, the skin on my nose and shoulders began to peel off in large flakes. My reinvention had begun.

In the 1980s, surfing was still part of the counterculture—Californian, vaguely disreputable, juvenile, macho. Surfers seemed to me the warrior class of beach people, nobler than the leathery fishermen drinking Budweiser off the pier and far more interesting than the boring families with their screaming kids or the spring breakers slurring and belching in the wind. There was a purpose in surfing, a hierarchy of skill and style, a social order with codes and rituals and music. Naturalistic and even spiritual, surfers sat on the beach and read the waves with squinted eyes, divining the wind and the sandbars before they even entered the water. Their casual nods of acknowledgement as I’d paddle by seemed full of portent. The big kahunas of the scene surfed nearest the pier—Pepe Morales and Trip House, David Mokry and Kenny O’Connor, surfers who could effortlessly curl into a glassy tube with magazine-worthy panache.

On a good day I might’ve gotten up the nerve to paddle within a few yards of them, but I feared invading their territory, afraid to get run over, or worse, wipe out and be ostracized as a kook, a grommet. Further down the sandbar were the lesser surfers, like me, but also the older generation of 1960s people who drove VW buses and used extra-long boards, which we mocked as “loggers.” Their weathered presence suggested a world that came before, of people who had been surfing Padre Island since the ’50s.

Though we shared the same beach culture as California—neon swimwear, Ocean Pacific T-shirts, bumper stickers declaring “Life’s a Beach”—Padre Island was, at best, a B-minus Santa Monica. Most of the world didn’t even know you could surf in Texas. And truthfully, most of the time you couldn’t. The water was warm, brown, filled with Portuguese man-of-war and sea lice, and the beach was pocked with a black tar that stuck to your feet and had to be rubbed off with baby oil. Fishermen hauled bull sharks from the same waters we surfed, and the sight of a hammerhead cruising through an oncoming swell was not unusual. In the spring, Padre Island filled with rowdies from UT and A&M, a seedy mélange of bikinis and beer, wet T-shirt contests, fistfights, Van Halen blaring from the radio, pot-bellied drinkers wearing big foam cowboy hats, and sloppy promiscuity in the dunes. A souvenir T-shirt depicted two sets of bare feet, one on top of the other, with the caption: “The damn sand gets into everything on Padre Island.”

At 15, this was paradise. When my cousin Daphne reputedly appeared in a crowded beach scene in The Legend of Billie Jean, the 1985 film shot on location on Padre Island and starring Helen Slater, it only added to the allure. To my dad, however, this was all a perfect vision of irresponsibility, a world of layabouts, beach bums, and ne’er-do-wells headed exactly nowhere. As a father, he was overprotective and strict, square and military, with distinct ideas about life’s winners and losers. When Little David took three months to build a bar in our kitchen one summer, disappearing for a week or more to surf, my dad’s attitude was clear: Don’t be like that.

The first surfer I met in junior high was Jacob O’Hearn, who had sun-streaked hair and walked with the unperturbed gait of a stoner. Jacob’s mother died when he was 8, and his father was a contractor who jokingly called his business the No Surf Construction Company because he only worked when the surf was flat. Jacob was on a surf team called Total Control, which had a clubhouse on Padre Island Drive where the owner shaped boards. Jacob and I met in woodshop class, flipping through issues of Surfer magazine as we endlessly ran hand sanders over our projects (mine was a clock shaped like Eddie Van Halen’s guitar). Jacob educated me on things like wave reports (local surf shop Benjamin’s had a phone number you could call) and which punk rock bands were cool (Black Flag, Corrosion of Conformity). That winter, Jacob invited me for a “dawn patrol” surf session, picking me up at 5:30 a.m. in his parents’ Oldsmobile. We drove to Bob Hall Pier, squeezed into our wet suits, and dove into the cold water with the sun peeking over the horizon. The dunes were empty, no fishermen on the pier, the wind blowing spray across the waves. Afterward we huddled in Jacob’s car, heat blasting, feet numb, wide awake and alive.

The following Monday, I walked through the halls of Cullen Junior High with a fresh identity. I was now a surfer. I joined Jacob at the cafeteria table, where a gaggle of MTV-informed and prematurely jaded misfits talked about skateboards, local punk shows, and Poi Dog Pondering. Jacob never mentioned that I didn’t catch a single wave during our session, an act of kindness I considered almost saint-like.

I never became a good surfer, only a semi-competent one. In high school, I began doodling pictures of my friend Kurt Riewe wiping out on big waves to make him laugh. I had invented a cartoon character named Surfin’ Sam—an avatar of my own insecurities, the hopeless kook—that I turned into a comic strip in my high school newspaper. Most of my time at Bob Hall Pier was spent paddling feverishly, cursing the white water, talking myself into lathers of self-loathing, willing myself toward the swells, and catching one or two waves if I was lucky. I was no Little David. And yet every attempt to catch a wave felt deeply personal, a test of will against the world, the desire to surf as powerful as the desire for identity itself.

Bob Hall Pier was a proving ground. Who was I if not a child of this water? My mom told me this was our native shore, and somehow I had to fit into it. Looking back, I was paddling madly against the invisible waves of a story that no one had yet told me, but which I knew in my bones was exactly here, at Bob Hall Pier. If I could only catch it.

With each wave, my parents become more human, both younger and older. They always told me their song from courtship was “Maggie May” by Rod Stewart. I never questioned how a song with the line “I wish I’d never seen your face” could be “their song.” Released the summer after I was born, it was about hard-won experience and heartache, bittersweet and haunted. You stole my heart, I couldn’t leave you if I tried …

I begin to see the shadow of the untold story on everything—how fragile and insecure my parents were in those vintage photos, how naive and unready, how they struggled to make a marriage and a family from the raw material of tragedy and circumstance. When my dad joined the Coast Guard in 1973, he requested that we be stationed in Corpus Christi, a place he personally detested (he called it “the armpit of the earth”) and had good reason never to want to return to again. After all, it was the site of the most painful episode of his life, one he kept secret for decades. The secret would be all around us—at Poppy’s house, on the naval base, along Padre Island Drive to Flour Bluff and down to Bob Hall Pier. And yet my parents returned to the Gulf Coast after the events of 1971, and again in 1976, and again seven years later. This was because my dad was devoted to my mom, who yearned to be near her family, near the ocean, near the stories that made her—that made us. I used to hear my mom and her sisters in the sunroom laughing uproariously, telling tales of the Old Bastard, family gossip that happened before I was born. I had little idea of the pain in it, the wounds, how I fit into it. I think back: No wonder they were so overprotective, as if I was a flame they were keeping lit against winds that had nearly blown them apart. And no wonder I constantly looked past my parents for answers—to Little David, to the next wave. There was a hole in my story.

Sometimes a place can hold truths that people can’t. When I was 15, Bob Hall Pier knew things I didn’t. It whispered histories and secrets my parents couldn’t bear to tell. A first glimpse of life’s horizons; how Hurricane Celia had spared the pier; how Celia had set me in motion. In lieu of the truth, my mom had invented myths. Starting in my teens, she told me I was the reincarnation of her mother, who died nearly two years before I was born. When I moved to New York to become a journalist, my mom saw it as destiny, shepherded by the ghost of Madeline, who had attended the Academy of the Dramatic Arts in New York in the 1930s in hopes of becoming an actress. Dreams deferred; dreams fulfilled. Another wave: Burdened by trauma and guilt, my mom had created a story in which the decision to keep me in 1971 was fated, inevitable, never in doubt. It was a kind of love story.

My shoulders are covered in freckles, a vestige of repeated sunburns while surfing at Padre Island 35 years ago. I wear that beach on my skin still. The waves come and go but Bob Hall Pier remains—mostly. Last year, Hurricane Hanna wiped out part of it, blowing the T-head down and leaving stretches of wood and cement submerged in water. It’s scheduled to be rebuilt, as it was in the past and probably will be again. It’s still a good place to drive on the beach and drink beer. And if you’re lucky, the surf will be up.