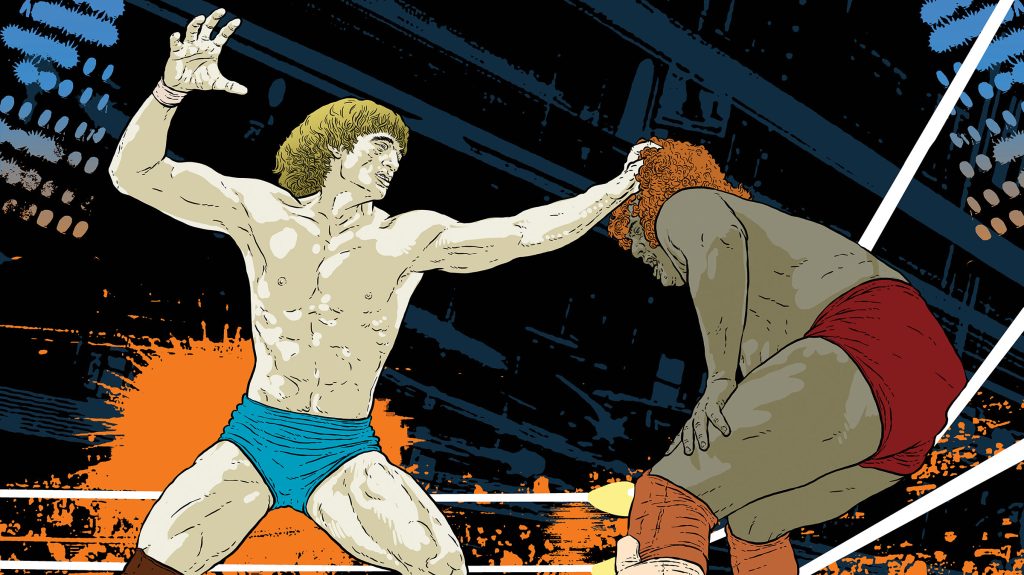

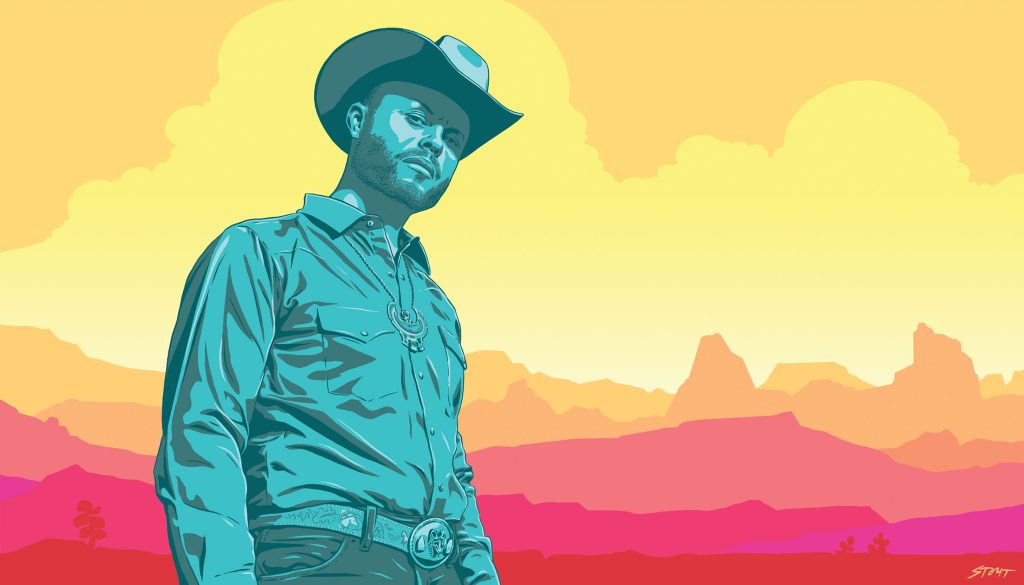

Illustration by Jason Stout

Charley Crockett was born in San Benito, the South Texas hometown of Freddy Fender. He came of age in Dallas, raised by a single mother struggling to get by. Crockett started performing on the streets of New Orleans’ French Quarter as a teenager while spending summers with an uncle who was a gambler and hustler. Later, he set out on his own, hoboing across the country and busking on street corners from New Orleans to New York to Paris.

Crockett draws on his gritty formative years in his music—a rootsy yet wholly contemporary country and western sound underpinned by the blues. A singer, songwriter, and bandleader, Crockett has recorded and released an improbable 10 albums in the past five years. The Americana Music Association took notice in 2021, honoring Crockett with its Emerging Act of the Year award. And last summer, he toured the nation as part of Willie Nelson’s Outlaw Music Festival caravan.

Crockett, 38, lives with his partner, Taylor Grace, just outside of Austin, though he’s on the road most of the time. His latest release, The Man From Waco, is a concept album of Western story-songs in a similar vein as Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger. Since the album’s release in the fall, Crockett has toured the U.S. and Europe with his Blue Drifters band, working their self-styled “Gulf & Western” sound that includes accordion, trumpet, and pedal steel along with guitars, bass, and drums. Crockett fronts the six-piece outfit with a retro-Western stage look topped by the coolest cowboy hats this side of Ernest Tubb’s Texas Troubadours.

Find Charley Crockett’s tour dates and records on his website.

Crockett is the real deal. He’s even related to Alamo hero Davy Crockett, according to a relative who traced the family tree. Sit down with him for a few minutes, and Crockett makes it clear he’s just getting started.

TH: What are your memories of being a child in the Rio Grande Valley?

CC: I have always seen myself as a barefoot kid standing in the caliche underneath mesquite trees—that’s the kid I remember. I always kept that with me. I imagine somebody moving to Chicago from the Mississippi Delta. I don’t think you’d ever get the Delta out of them. I believe the Valley has that same kind of effect on anybody who’s born there. The Valley is like the Delta or Appalachia, but no one gives it any credit.

TH: What was your upbringing like?

CC: My momma was a single woman trying to raise a kid in a man’s corporate world in Dallas without an education. It wasn’t easy. She wasn’t around much because she was working all the time—working all the time to give me a chance to change my situation.

TH: How did Dallas rub off on you?

CC: It’s the unsung, third great blues city. That roots music triangle to me is New Orleans, Memphis, and Dallas. I lived a thankless, backdoor, single momma, blue-collar life in Dallas, and it was hard. That’s why I had no problem going to New Orleans every summer with my uncle. New Orleans is a hard place, but it cradles you in a way that Dallas does not. Dallas is fast. Dallas is where Benny Binion ran the tables. Dallas is where they couldn’t foil the plot to kill Kennedy, you know? That’s a hard town. I was trying to get out of there. And the kind of blues music, the kind of Dallas sound that rubbed off on me, I really believe came from how hard a town it is. It’s like Memphis, but a lot bigger, and they don’t acknowledge their cultural history. But it’s in every backroom.

TH: You’ve cited blues jams around Dallas as a big influence.

CC: The blues jam was an open format that was beyond open mic. That’s how I learned to lead bands for real and communicate with people who were plugged in on stages in front of a microphone where money was on the line for the establishment. I learned that through the blues jam more than anywhere else. Because I would get thrown off those stages when it didn’t work out. You either quit and go do something else, or you adapt. And that’s when I started learning. You gotta play a 1-4-5 and give the band something they can follow easily. Then maybe you can start veering off into some of your other material.

TH: How did you take an interest in old roots music?

CC: Performing on the street in New Orleans and Dallas and New York City and San Francisco, you start absorbing. There’s a different sound in the street. You’re going to hear a lot of pretty good music if you’re on the subway in New York, better than you would maybe hear on the radio. I was hearing the great jazz, freestyle jazz players in New York. In New Orleans, I was hearing nothing but old school New Orleans jazz. They were playing nothing but old time.

TH: What did you learn from busking and hoboing around the country?

CC: It’s everything. The way I run my business today is the exact same way I did when it was just me playing out of the guitar case. I learned how to lead bands. I learned how to handle money. I learned how to deal with the promoter. It’s the same game. What I’m doing now is just more political and amplified.

TH: You’ve mentioned before that you don’t read music.

CC: A lot of the early Carter Family stuff that I learned were these beautiful, simple stories. I know a lot of other old folk songs too like “Short Life of Trouble,” “Darlin,’” “Six Months Ain’t Long,” “Lonesome Homesick Blues”—the Carter family one—“March Winds Gonna Blow All My Blues Away,” “Sitting on Top of the World,” and “They Call That Religion,” all those Mississippi Sheiks songs. I learned that music because I could remember it. I never have written anything down, even the songs for this new record. I just memorize ’em. I think that’s how a lot of people used to do it. I have a hard time seeing George Jones writing anything down, don’t you?

TH: You had to step away from the road for a few months in 2019 for surgery to repair a faulty heart valve. How have you been?

CC: When you have a heart defect, you start thinking, “Man, did the Creator make me flawed? Why did the Creator intend for me to leave so early?” You ask these questions and then you wonder, “Should I even be asking that question?” But it happens because you’re aware of it, knowing you got a long line on your chest. I wasn’t smart enough to realize what was going on; I just got lucky. I almost died in the back of the bus. I’ve got multiple issues that are related, and it causes these bigger problems, you know. I just honestly feel like the Creator let me stay a little longer because for all my shortcomings, I kept just putting the music first. I feel like it’s my purpose. And I do think you get rewarded in some little way by following your heart.

TH: How have you held onto your Texan-ness as your career has grown?

CC: I got all these managers calling me saying, “Look, Charley, you know the world is bigger than Texas.” I know this sounds brash, but this is the policy that I have adopted going forward: The world is not bigger than Texas. There is only Texas, and we take Texas to the world. That’s what I have to do. That’s how Stevie Ray Vaughan did it, that’s how ZZ Top did it, that’s how Willie done it, that’s how Selena did it, that’s how Freddy Fender did it.