San Antonio’s storied waterway snakes through attractions historic and new

By Wes Ferguson \ Photographs by Tiffany Hofeldt

The San Antonio River’s Mission Reach

When Hank Lee opened an art gallery next to the San Antonio River in 1989, his new neighbors in San Antonio’s Southtown area included free-ranging flocks of chickens scratching the dirt. Women who lived across the river from his gallery were always giving him oranges from backyard trees. And the river itself—the alluring, spring-fed stream that had sustained human life for some 11,000 years—was all but a memory, having been replaced by a concrete drainage ditch. One mile downstream from the heart of the city, San Antonio’s world-famous River Walk did not yet extend this far south.

“It was just a dirt trail,” recalls Lee, who still owns and operates San Angel Folk Art Gallery at Blue Star Arts Complex on South Alamo Street.

For decades in San Antonio, there was the downtown River Walk: the “American Venice,” with its sunken gardens, wide promenades, and colorful boats to ferry tourists along a ribbon of green water, all of it winding gently through the middle of the city. The rest of the river was more of an afterthought. “It was an embarrassment,” says Frates Seeligson, the executive director of the San Antonio River Foundation. “Everyone thinks of the river as what we call the downtown loop, which is where the majority of the restaurants are and most of the tourism takes place. But if you’re from San Antonio, you know that there were other parts of the river that had been neglected and were basically urban blight.”

The river’s woes grew from good intentions. In response to a series of devastating storms—most notably the 1921 flood, which claimed more than 50 and perhaps as many as 89 victims—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers “channelized” long stretches of the river during the mid-20th century. This straightened the San Antonio’s once-meandering course through the city and replaced its natural bed and banks with concrete. “It was a trapezoidal ditch that was highly effective at moving floodwater,” Seeligson says, “but it was devoid of habitat for native fauna and flora, and there were no recreational elements for citizens.”

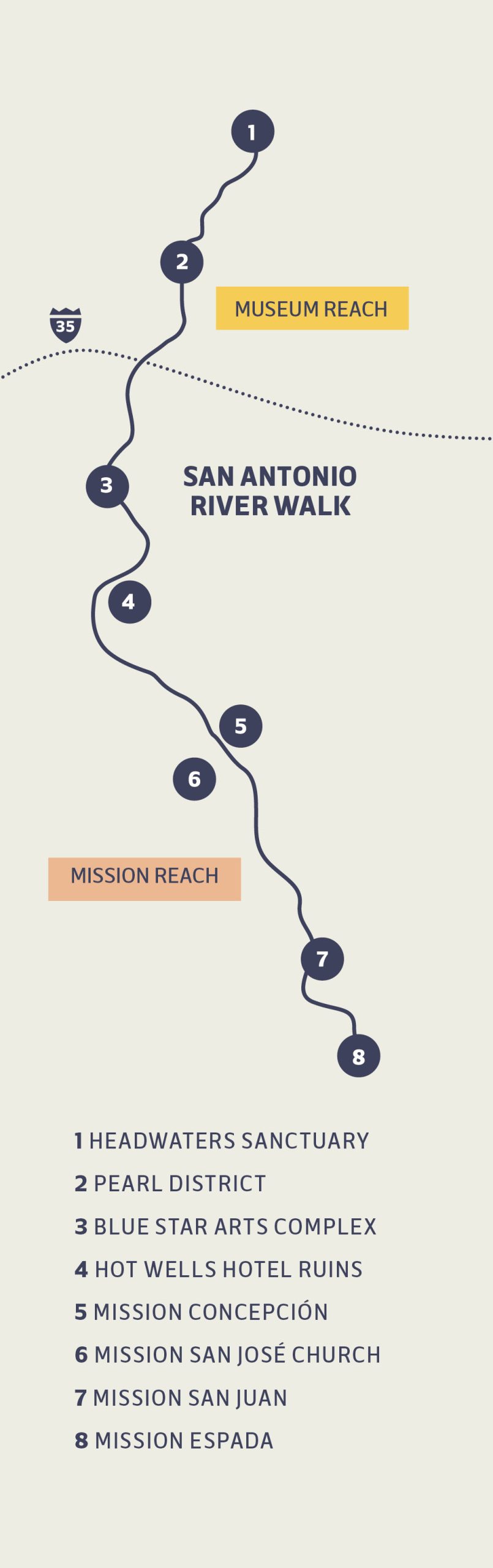

That began to change about a quarter-century ago. First, in 2007 San Antonio extended the River Walk 3.5 miles north, linking downtown with the old Pearl Brewery and Brackenridge Park, home to the city’s zoo and the historic Japanese Tea Garden. Because this section connects the Witte Museum and the San Antonio Museum of Art, it came to be known as Museum Reach. South of downtown, the River Walk was extended 8 miles. The San Antonio River Authority and other organizations also scrapped the artificial flood-control channel, returning the river to a more natural and inviting appearance and restoring its ecological value to native fish and migratory birds. Because it links four of San Antonio’s five colonial Spanish missions—all of them save the Alamo—this section of the River Walk is called Mission Reach.

During family vacations as a child, I recall being mesmerized by the downtown River Walk. We’d be walking on a busy urban street, and out of nowhere, it seemed, a stone-masoned staircase delivered us to a lush and hidden world below, where bald cypress trees cast their cooling shade and footbridges arched across the water. I distinctly remember liking the ducks. The margaritas in the patio cafés drew me back as a young adult. During more recent visits to the Spanish missions and the Pearl and points in between, I kept finding myself on the River Walk, like a ribbon tying together the city’s most historic landmarks. Was the extended River Walk reason enough to visit San Antonio again? This spring, I decided to find out.

On a bright and breezy Sunday in March, my wife, Laura, and I arrive just south of downtown South Antonio, in the King William Historic District, a lovely neighborhood of Victorian homes once nicknamed Sauerkraut Bend for the many Germans who arrived there in the 1840s and ’50s. The settlement was named after Kaiser Wilhelm of Prussia, the emperor of Germany at the time.

Owner Sarah Neal rents kayaks and canoes at Mission Adventure Tours

Colorful fleets of kayaks paddle the tranquil river below as we cross a bridge to the Guenther House, a waterfront restaurant and museum in the homestead of German immigrant and entrepreneur Carl Guenther, who used water from the river to power San Antonio’s first flour mill. To my surprise, the business that grew from Guenther’s mill, now called Pioneer Flour Mills, still operates on the property, and the restaurant is best known for biscuits and pancakes baked with the company’s own flour. The wait for a table on this spring day is two-and-a-half hours, so we add our names to the list and wander across the street to the Blue Star Arts Complex, home to an eclectic mix of art galleries, a brewery, and bars within a complex of warehouses originally used for ice and cold storage.

That’s where we meet Lee, who is tending the register and chatting up customers browsing the art at San Angel Folk Art Gallery. All around him, from floor to ceiling, hang intricate paintings, handmade masks, wooden sculptures, and tapestries, most from Latin America. Lee is a little wistful for the old days when his stretch of river was more escondido, or hidden. “We’d all meet down there and walk our dogs. We had so many picnics on the river,” he says. “Now it’s been commodified a little bit. It opened up our secret, and the word got out. Now it’s more of a destination.”

But Lee likes the new version too. “When the River Walk was just downtown, people from San Antonio didn’t really use it, unless you had somebody coming to town,” he says. “By expanding it north and south, the people in the city use it and embrace it, which is something that never happened before.”

We’re too hungry to keep waiting for our table at the Guenther House, so Lee recommends we trek a few blocks north of the river to Liberty Bar, a funky restaurant in a two-story pink building that dates to 1883 and once served as a Benedictine convent. Lee swears by the queso de cabra con piloncillo, an appetizer of creamy goat cheese drizzled with Mexican cane syrup and schmeared on house-baked toast. The dish is so rich and delicious, it could have sufficed as our entire meal.

Back on the River Walk after lunch, we head downstream from King William and Blue Star, where much of the urban development begins to give way to restored native grasslands and riparian forest. The sounds of nearby traffic are among the only reminders we’re in the middle of Texas’ second-largest metropolitan area, home to 2.4 million people. At about the midpoint of the Mission Reach, the River Walk arrives at the Hot Wells Hotel ruins, a fascinating site that only opened to the public in 2019.

More than a century ago, the health spa and resort attracted some of the most famous movie stars of the day, including Will Rogers and Charlie Chaplin, as well as such dignitaries as Teddy Roosevelt, to bathe in its sulfurous waters from a nearby mineral well. In 1910, the first movie studio in Texas, Star Film Ranch, opened across the river from Hot Wells and was connected by a swinging footbridge. In the 1890s, there was even a zoo with a black bear supplied by Judge Roy Bean, the law west of the Pecos.

“The history just tickles me to death,” says Yvonne Katz, the president of Hot Wells Conservancy.

The Hot Wells complex was repeatedly destroyed by fire over the years, but a stroll on the grounds still reveals the bathhouse’s former grandeur. As San Antonio emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, Katz says she’s excited to reintroduce public events at the ruins, including silent film screenings, concerts, and a series of harvest feasts in the fall.

The largest of San Antonio’s missions, San José, lies almost directly across the river from Hot Wells. As we stroll between the two historic landmarks, families fish from the riverbank and groups of cyclists pedal past, with ample room to share the paved trail with pedestrians. Native stones and tall grasses protect the sloping landscape from erosion. On the water, sunlight sparkles in the ripples.

“It’s all revitalized nature with natural banks, so you forget that you’re in the city,” says Sarah Neal, a kayak guide and owner of Mission Adventure Tours who I called after my visit. There’s also more current in the river this far downstream, and a series of 1-foot-deep ladders that allow fish to swim upstream also serve as kayak chutes for paddlers. “They’re easier than they look,” Neal says of the chutes, noting they’re perfectly safe for beginners. “You just sit there and let the water take you.”

Mission Adventure also provides kayak and stand-up paddleboard tours of the King William neighborhood and Museum Reach, as well as cycling tours of the River Walk with both pedal and electric bikes.

The Mission Reach of the River Walk ends at San Antonio’s southernmost Spanish mission, Espada, which was completed in 1756 with native limestone and a distinctive tower with not one but three church bells. Also still standing on the mission site is the nation’s oldest acequia, or community-operated canal, which diverts water from the San Antonio River to irrigate the farm fields that once surrounded the mission.

After our stroll on Mission Reach, it’s time for a nap. For years, I’d been hankering to stay in the one-of-a-kind Hotel Emma. Happily for me, the city’s most expensive boutique hotel is situated on the banks of the San Antonio River, on the grounds of the old Pearl Brewery. Since closing in 2001, the brewery complex and its stately buildings have been preserved and reimagined as a community gathering place with plazas and patios, shops, high-end restaurants, a year-round farmers market, and a food hall in the old bottling plant. The renovation draws scores of locals and visitors to a part of San Antonio that had been economically depressed and riddled with crime before its renewal as a citywide destination. In addition to a rooftop pool, the 146-room hotel in the repurposed seven-story brewhouse is appointed with folk art curated by Lee. Complimentary margaritas are served in an elegant, two-tiered library of 3,700 books donated by San Antonio author Sherry Kafka Wagner.

In the evening, we venture back onto the River Walk and begin the leisurely walk downstream from the Pearl, confident we will quickly find a good place to eat and relax. Soon, we come to a charming art installation where a giant school of fiberglass fish—hand-painted to resemble the native long-eared sunfish—dangle from beneath the Interstate 35 overpass next to the San Antonio Museum of Art, which also sits on the river and occupies the former Lone Star Brewery complex.

We’ve been walking for less than 10 minutes when we come to a lively outdoor bar and conglomeration of food trucks called El Camino SA. Although we feel like two of the oldest people on the scene, we are rewarded with a plate of birria tacos filled with rich beef and melted cheese, which we dunk in consommé before gobbling down. From our picnic table, I happen to notice a much older place next door: a white Neoclassical mansion with Corinthian columns and an impressive wraparound balcony and porch. At the gateway is a wrought-iron arch proclaiming the spot as the oldest Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Texas. Upon finishing our tacos, we head to Sam Houston VFW Post 76, where I timidly ask a man who is sweeping the parking lot if the public is allowed to have a look around. “Everyone is welcome here,” he assures us.

Sam Houston VFW Post 76

Inside the nearly 130-year-old mansion, parents and grandparents chat and chuckle among themselves as children play underfoot. The George Strait song on the jukebox is a welcome break from the bumping music next door, and the $2.50 longnecks we order strike me as probably the cheapest beers on the River Walk. From a picnic table above the river, we watch colors splash on the water’s surface as the golden hour arrives, and couples pass by hand-in-hand. On our walk back to the hotel, the art installation of giant sunfish glows in the dark, rendering them even more eye-catching.

There is still one more spot on the river I want to check out, so the next morning, Laura and I head upstream from the Pearl. The River Walk ends near the northern edge of Brackenridge Park, across the street from the University of the Incarnate Word, which is home to the historical headwaters of the San Antonio River. We drive to see the headwaters, parking on campus, then cross a footbridge followed by a short walk to Blue Hole, a rock-walled well that is said to have been a gushing fountain before extensive pumping from area wells began to interfere. I am disappointed to learn the main spring no longer flows regularly, the aquifer below the springs having been depleted long ago. “I have seen this bold, bubbling, laughing river dwindle and fade away,” wrote George Washington Brackenridge, the prominent San Antonio banker and philanthropist, to a friend around the time he sold the headwaters to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word in 1897. “This river is my child and it is dying, and I cannot stay here to see its last gasps. … I must go.” Although Brackenridge is long gone, he lives on as the namesake of nearby Brackenridge Park, and Blue Hole remains a peaceful place to sit among the live oaks and palmettos, a pocket of solitude in the bustling city.

Seeligson, the River Foundation executive director, is confident the River Walk will be extended to Blue Hole in the next two to four years, uniting the entire river through the heart of San Antonio. There are further plans to restore habitat and build trails along San Pedro Creek and its tributaries—Alazan, Apache, and Martinez creeks—linking the river with traditionally underserved areas on San Antonio’s West Side and following some of the same corridors that were devastated by the historic 1921 flood more than a century earlier. The city’s effort to restore the river and extend the River Walk has already resulted in billions of dollars in private investment along the riverbanks, Seeligson says. Trail use has steadily increased year after year.

“The reason why the first peoples even showed up to this area—the Native Americans, Spaniards, all of the growth—is because of that beautiful river, and it had been neglected for too long,” he says. “For a lot of people who’d left the urban core, it’s given them a reason to come back. They’ve reclaimed their river.”