Animals Crossing

Wildlife agencies work across borders to protect rare species

By Melissa Gaskill

Borders can be a big deal to humans, but the habitats of wild creatures transcend lines drawn on paper. Along the Texas-Mexico border, for example, animals like ocelots, beavers, and black bears rely on habitat in both countries.

In fact, if wildlife could not freely cross the border, Big Bend National Park would have no black bears, according to Thomas Athens, a wildlife biologist at the park. The species was eliminated from the U.S. in the 1940s, but in the late 1980s, bears began crossing on their own from Mexico. “To this day, they still move back and forth in search of food and new territory,” Athens says. “The park area can only support 25 to 30 bears, so it’s important for them to be able to cross.”

The Lower Rio Grande Valley, while mostly urbanized, ranks as one of the most biodiverse areas in the U.S., and the region is home to more than 20 public venues for wildlife viewing and world-class birding.

A River Runs Through It

Wildlife professionals in Texas have strong relationships with their counterparts at government agencies and conservation groups across the border in Mexico. A joint project in the Big Bend area is removing nonnative plants along the river. “Invasive species can be really hard to control if you’re not working closely together, so we’re lucky to have such a good relationship,” Athens says.

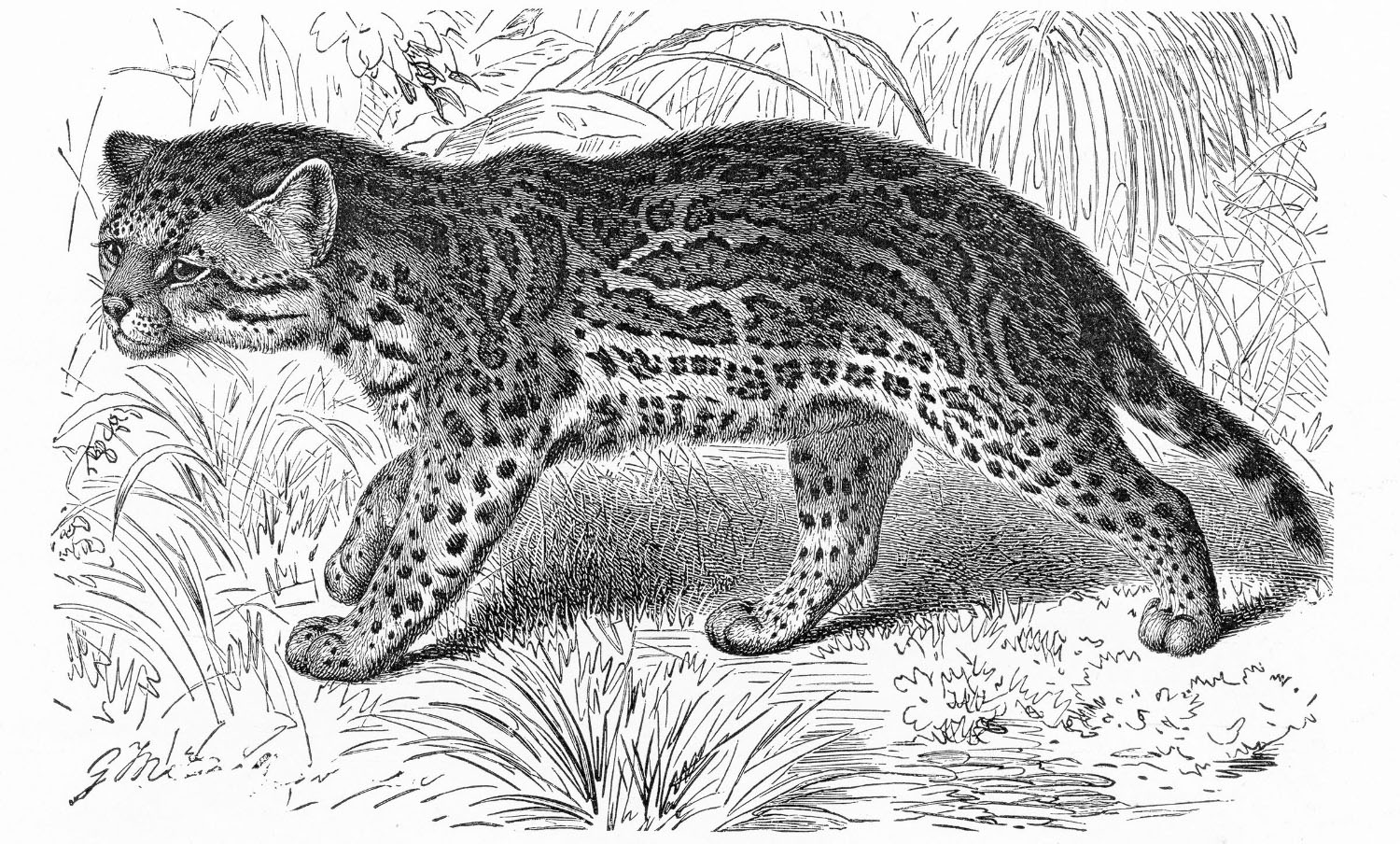

Multiple parties on both sides work to protect ocelots, too, says George Garcia, visitors services manager at Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge. “We’re in constant communication with the agencies in Mexico,” Garcia says. “We have a good partnership and all have the same goal of improving the genetic diversity and restoring habitat.” For information on volunteer opportunities at the refuge, visit fws.gov/refuge/laguna-atascosa.

Birds of a Feather

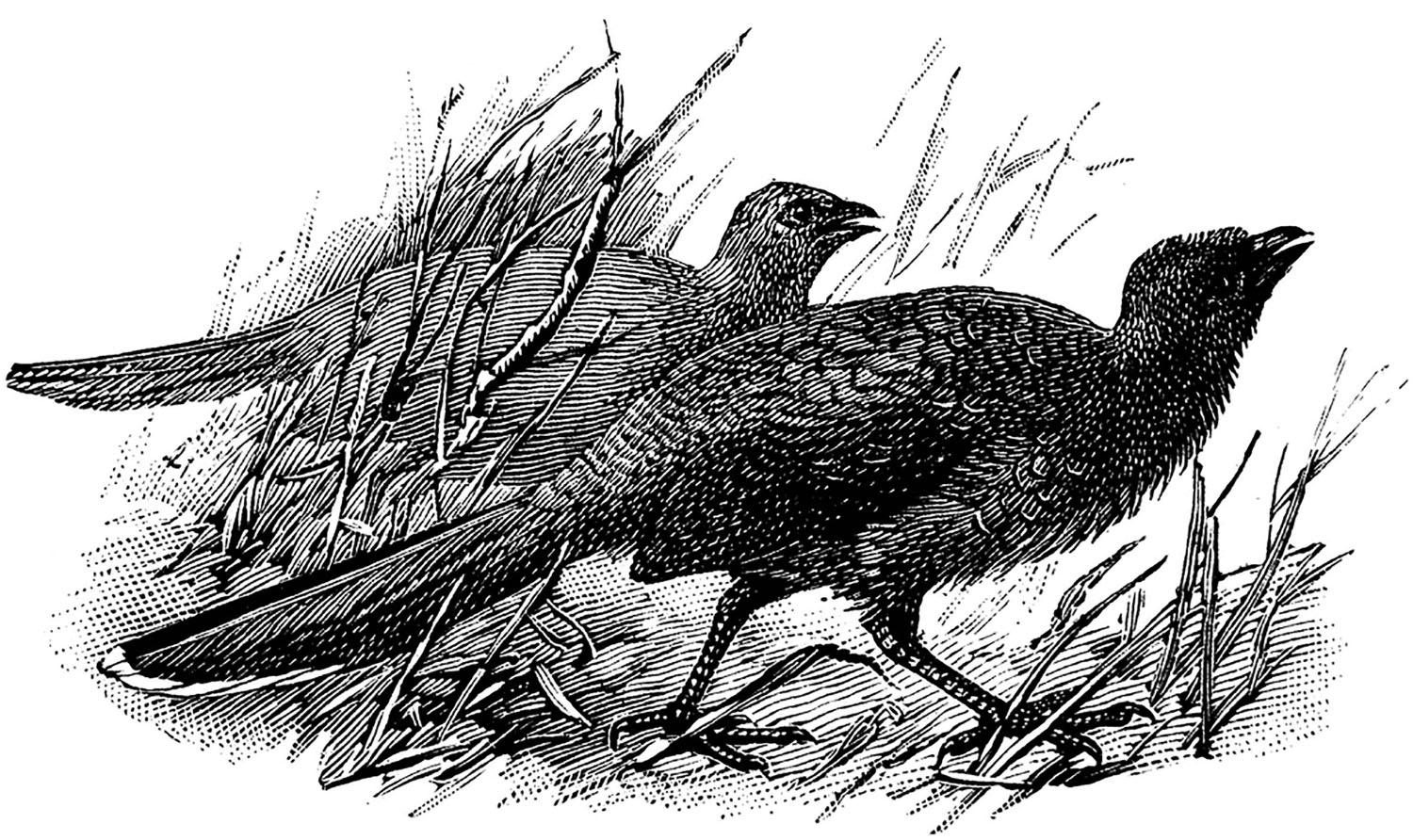

The Nature Conservancy’s Lennox Foundation Southmost Preserve, which hugs the twists and turns of the Rio Grande south of Brownsville, contains one of two remaining stands of native Mexican sabal palm and Tamaulipan thornscrub in the country. Among the many species that need the habitat on both sides of the border are raucous chachalacas and colorful green jays, says Sonia Najera, TNC Coastal Plains Project director. The preserve’s spot along the coastal flyway makes it a prime location for the birds. “They have no problem crossing the border and finding habitat on both sides,” Najera says, aside from issues with stretches of border wall. Southmost Preserve is closed to the public, but see the “In Plain Sight” sidebar for information on wildlife viewing in the area.

118

Miles of the Texas-Mexico border within Big Bend National Park

50-80

Estimated number of ocelots remaining in the U.S.

110,000

Acres in the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge

Cross-Country Travelers

Journeying north and south of the border is a common pastime for these wild creatures.

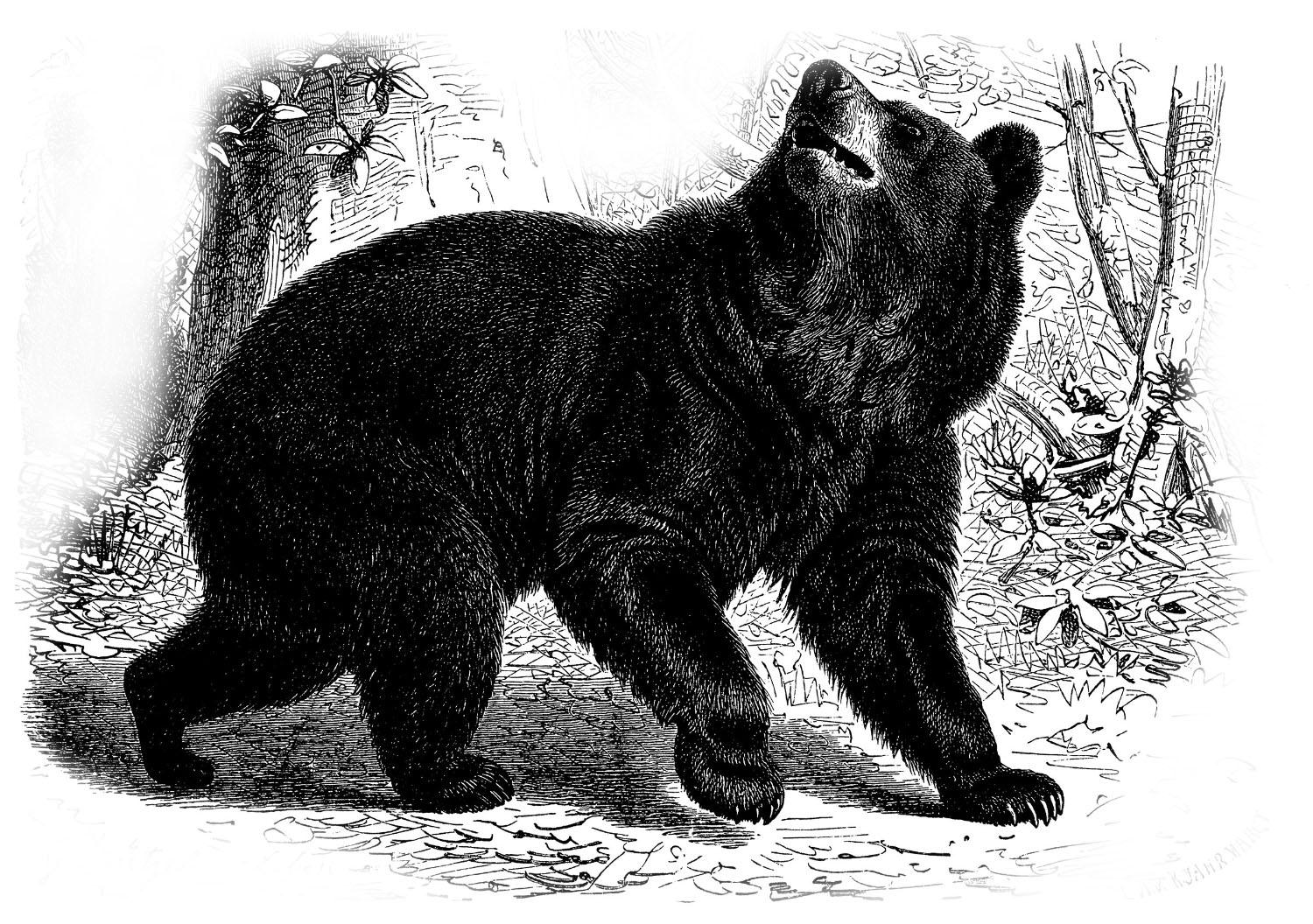

Black bear

Black bear

Ursus americanus

Habitat: desert scrub or woodland within scattered mountain ranges

Plain chachalaca

Plain chachalaca

Ortalis vetula

Habitat: brushy and thorny forests along streams

Bighorn or Mountain sheep

Bighorn or Mountain sheep

Ovis canadensis

Habitat: rugged, mountainous terrain with sparse vegetation

Ocelot

Ocelot

Leopardus pardalis

Habitat: dense, thorny, low brush

Rio Grande Beaver

Rio Grande Beaver

Castor canadensis mexicanus

Habitat: the Rio Grande and nearby ponds

In Plain Sight

The best chance to see black bears in Texas is by driving or hiking in Big Bend National Park’s Chisos Basin. A majority of the bears’ range in the park is contained in the basin’s roughly 40 square miles.

A small population of bighorn sheep—fewer than 14—remains in Big Bend National Park’s Persimmon Gap and Deadhorse Mountains areas. The Black Gap Wildlife Management Area, open year-round on the park’s northeast corner, has a larger population.

Kayak or canoe on the Rio Grande to look for beavers. Rather than constructing dams, this subspecies builds bank dens in muddy river banks.

Santa Anna National Wildlife Refuge is open every day from sunup to sundown. Ocelots live in the area but are small and elusive, so few people have seen them.

See chachalacas, green jays, and more species of birds in the Rio Grande Valley at Resaca de la Palma, Estero Llano Grande, and Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley state parks; and World Birding Center sites along the border between South Padre Island and Roma.