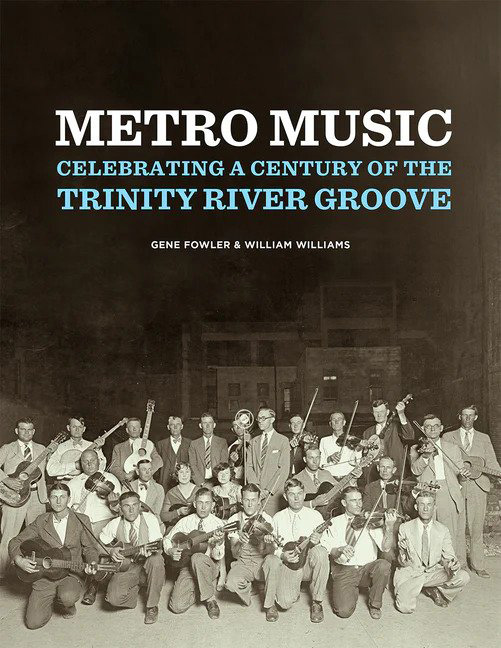

Gene Fowler and William Williams spent more than a decade researching, collecting, and writing Metro Music: Celebrating a Century of the Trinity River Groove. By diving deep into a subject that may appear regional and arcane on the surface, the two music historians actually uncovered a story with universal resonance—one of humans and music.

The book’s roughly 500 photographs, accompanied by extended captions, focus on the music industry of the Dallas-Fort Worth area from the late 19th century through most of the 20th century. The book, released in March, introduces readers to people of all ages, genders, and styles but with a shared interest in music, that mysterious muse that brings out emotions like no other form of communication.

The people who make the music are no less ethereal.

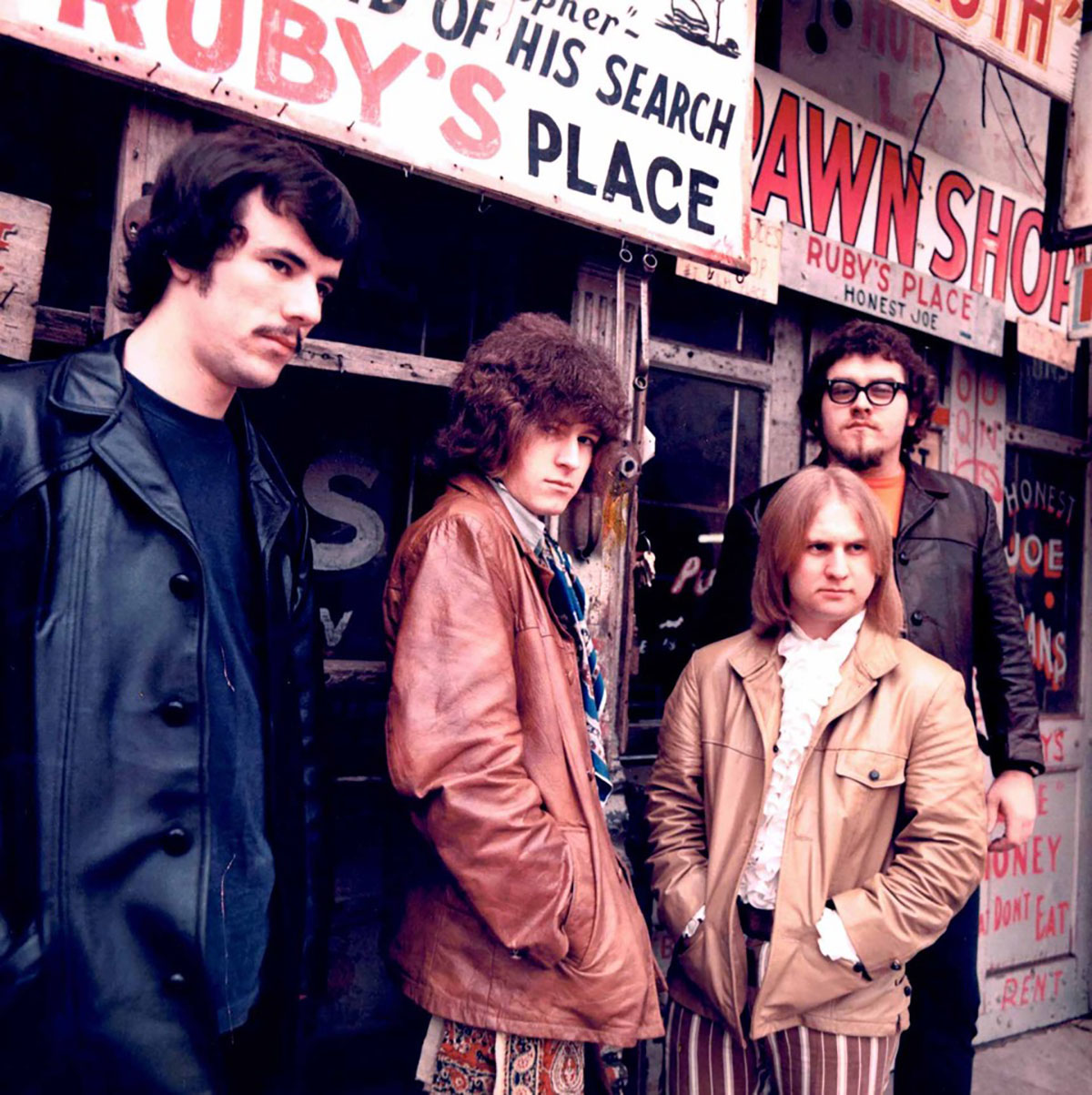

There never was a North Texas sound, per se. But in their research, Fowler and Williams uncovered a multitude of different sounds being made by all kinds of people. The Masked Singers (on the radio, no less); The Werewolves; Big Bo Thomas; the Belew Twins and other kid acts; gospel singers; rock combos; orchestras and swing bands that played live on the radio; women playing accordions; orquestas and conjuntos… They all testify to the wide breadth of music in North Texas.

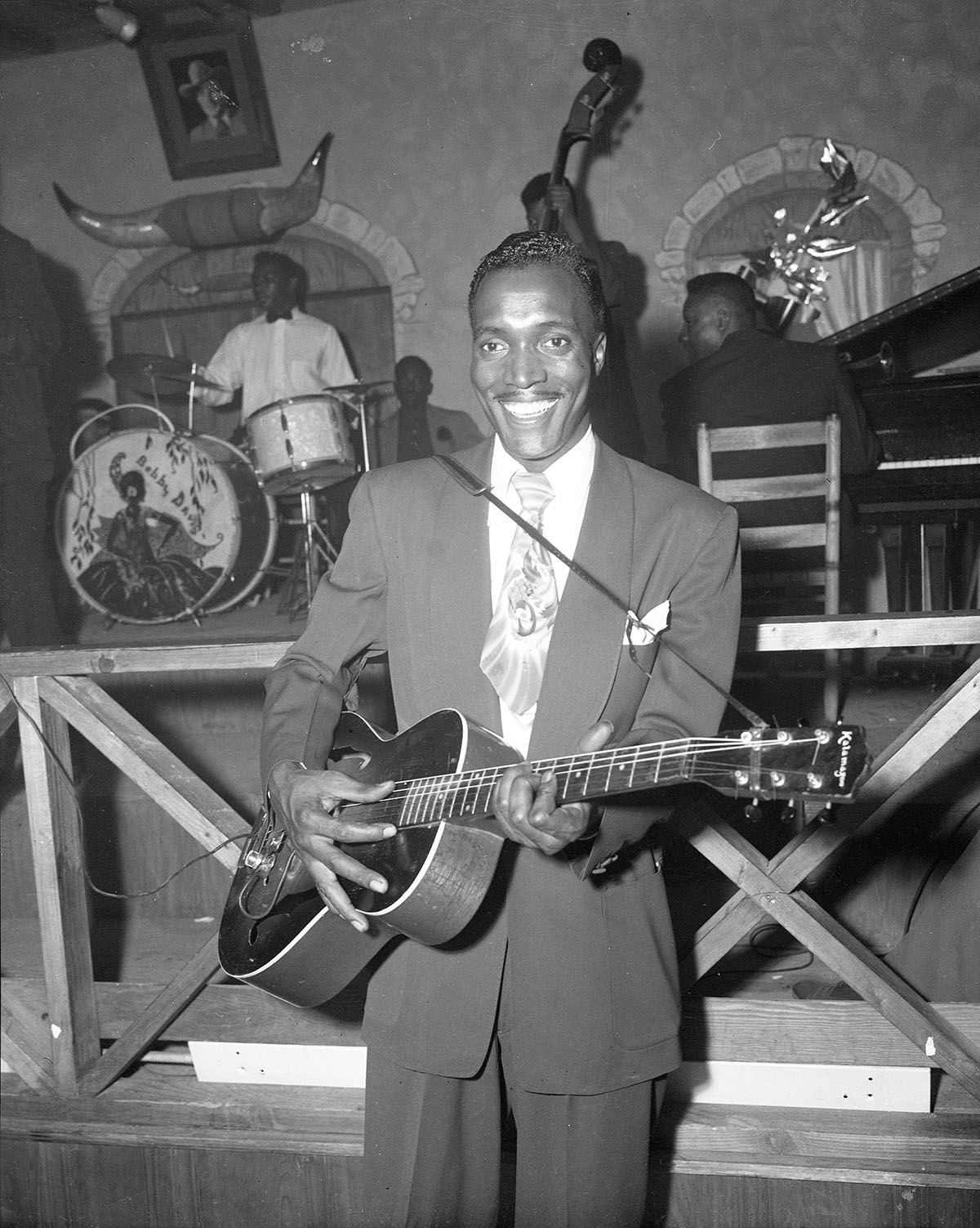

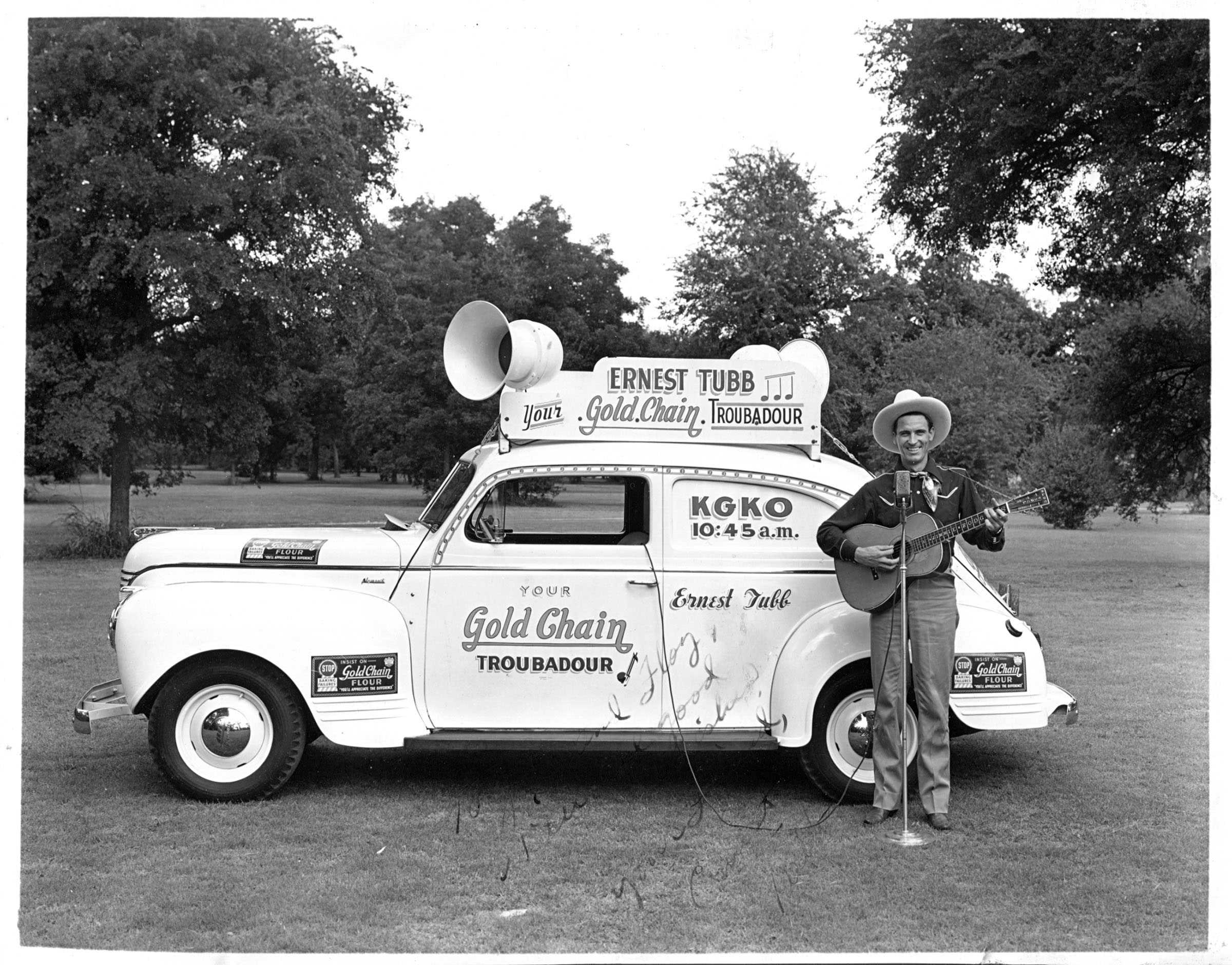

Some of the musicians pictured in the book are famous and familiar: Bob Wills, Ernest Tubb, Delbert McClinton, Jimmie and Stevie Vaughan, and Robert Ealey to name a few. The obscure, unknowns (to me), and never-weres depicted here are no less interesting: Cecil Luna’s Rhythm Kings; preacher man Darrell Jessup and his double neck steel guitar, steel legend Tommy Morrell; Charlie Mitchell and the Southern Stars; Joe Wilson and the Sabers; Rev. Fillmore & The Swingin’ Flames.

The cover of Metro Music. Photographed in 1930 on Houston Street in Fort Worth, this image of fiddlers, guitarists, and other musicians includes a young Bob Wills (first row, second from right) months before joining the Light Crust Doughboys on his way to becoming the King of Western Swing. Photo courtesy of Carolyn Wills.

Metro Music, which was released by TCU Press in March, also includes the ancillary and too often uncredited elements of the music industry, such as radio technicians, producers, studios, disc jockeys, weekly stage reviews, clubs, and club owners. Jack Ruby even gets his own chapter. A mustachioed Angus Wynne III—a longtime DFW concert producer—working the walkie-talkie at Texas International Pop Fest in 1969 as promoter of the event says as much about the ’60s as most of the bands do.

But it’s the musicians in the group photos keep drawing me back, like a curious anthropologist, to ponder faces and poses, wonder and guess. What was their life like? What did their music sound like? Who was their audience? Did they have a day job? Did the family approve of music? Who was the cut up in the group? Who called the shots in the enterprise?

Their outfits speak of many versions of Texas music. Bands dressed like charros and Beatles, decked out in sparkling powder blue tuxes with bulldog ties, in business suits, matching bow ties, matching flyaway collars, matching cowboy hats. The Western Starlighters, with their matching sky-high brim Western hats, long neck kerchiefs, tight pants, and fancy boots, manage to out-Troubadour the Texas Troubadours.

Most musicians pictured in Metro Music did not achieve much fame or enjoy financial riches. But posing with a fiddle or guitar or bass or drumsticks in hand, accordion strapped on, or behind a microphone, each player projects the power of musical performance. Individually, they were musicians. When they got together, they became part of a band that created a sound. Every player had a role. They were somebody.

You don’t have to hear these bands to understand their allure. You can see it right here in the pages of Metro Music. These are people who would do anything for music. They did—and it shows.