During the growing season in the Chihuahuan Desert west of Fort Stockton, pumps are engaged to irrigate fields of pecan, wheat, alfalfa, hay, and cotton. That has left nearby Comanche Springs, once the largest complex of freshwater springs in West Texas, a jumble of dry rocks within a metal cage by the edge of the Comanche Springs swimming pool. Only during the summer does water materialize, and it’s chlorinated city water for the pool.

But over the past seven winters, nature has begun to run a different course. When those irrigation pumps were idle, Comanche Springs began to flow again, usually from November through April. Old-timers started talking up the glory days of the Water Carnival, an annual event that earned Fort Stockton the nickname “Spring City of Texas.”

Robert Mace, executive director of The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, observed the springs’ return during fallow months a few years ago. Mace is a hydrologist by training and a springs geek by passion. He enjoys visiting sites with springs around Texas and has documented what was left of Comanche Springs on several occasions. But on this visit, he saw a steadily gushing fountain of chilly artesian water cover the jumble of rocks behind the chain-link fence. Children were splashing around canals and pulling up crawfish in early March.

“What would it take to bring the springs back?” Mace wondered. A year-round flow could provide a low-cost booster shot to the local economy. “How much does it cost to pay farmers not to farm and bring value to the community by bringing back the springs?”

Courtesy Robert Mace

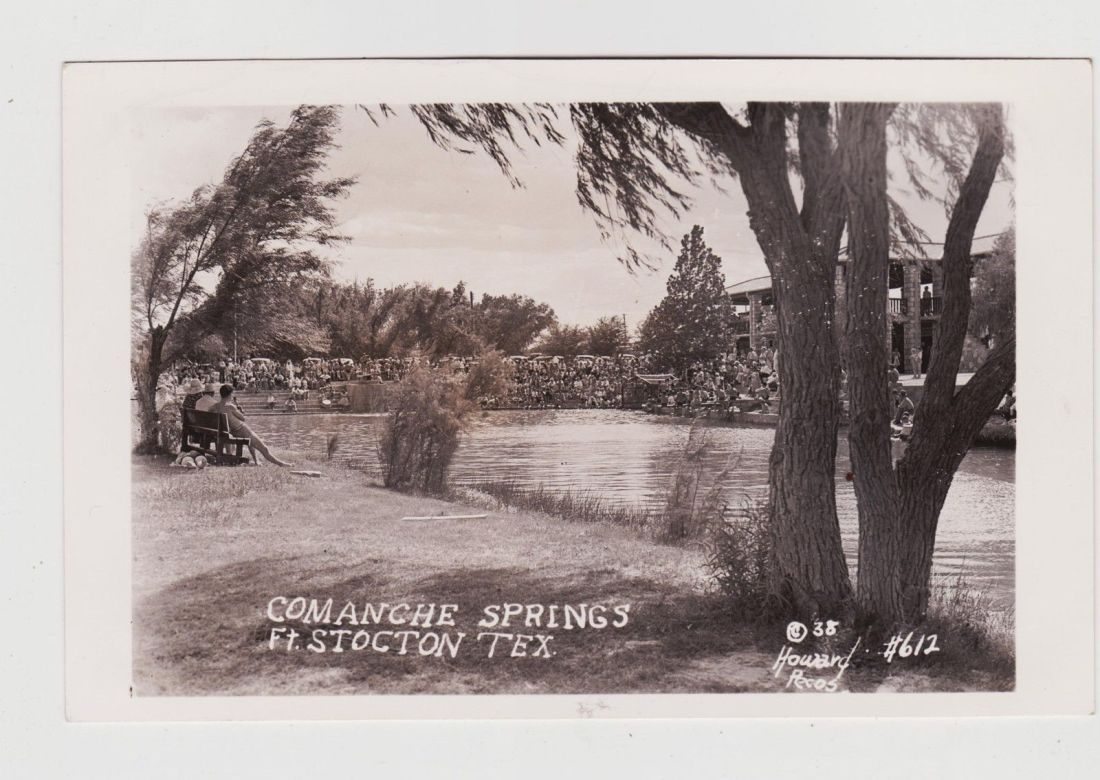

For thousands of years, Comanche Springs provided sustenance to humans traveling across the Chihuahuan Desert. The prodigious springs, producing up 35 million gallons a day, attracted numerous Indian tribes, Spanish colonialists, Buffalo Soldiers at the conclusion of the Civil War, pioneering settlers headed west, and families of Mexican and European descent who put down stakes in the area because of the water.

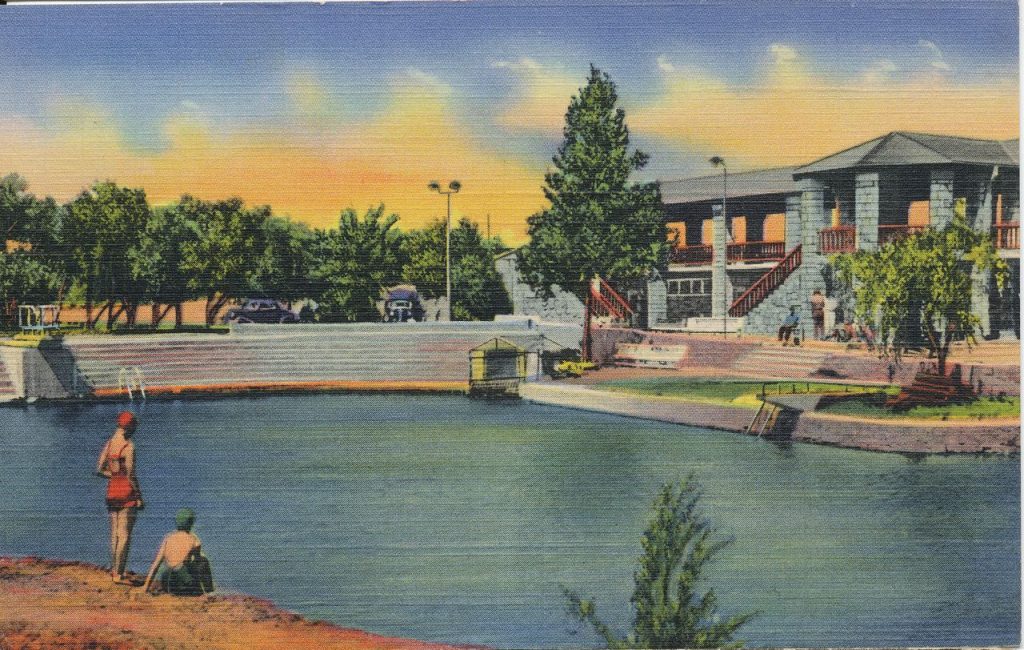

In the late 19th century, a military fort and the town of Fort Stockton grew around the springs. These water sources flowed into canals that snaked for miles out of town, providing sustenance to more than 100 small family farms spread over 2,000 acres east of town. In town, a pool and pavilion were constructed around and above the biggest spring, Big Chief Spring, in 1938. Around then, the inaugural Water Carnival took place.

But Fort Stockton’s reputation began to diminish in the early 1950s, when motor-powered pumps and center-pivot technology made irrigated farming viable in the desert west of town. Pumping groundwater for crops had the unintended consequence of drying up Comanche Springs and cutting off water from the small family farmers east of town. This became an extremely contentious issue that pitted neighbor against neighbor.

In 1954, the Texas Supreme Court stepped in and upheld Rule of Capture, a remnant of British common law that states a landowner owns all the water beneath their property. The decision ratified the right of irrigators west of town to pump as much water as they wished from under the land they owned, even if such pumping negatively impacted other users of groundwater. (Today, Texas is the only western state where Rule of Capture, rather than Reasonable Use, governs use of groundwater.)

Courtesy Robert Mace

Mace wasn’t the only one who thought there was a way to keep Comanche Springs flowing year-round. Sharlene Leurig, a Meadows Center fellow and CEO of Texas Water Trade, a nonprofit established in 2019 to utilize market solutions for water conservation and environmental flow, saw the potential, too. Together, Leurig and Mace started talking to community stakeholders, including the Middle Pecos Groundwater Conservation District and irrigated farming operations west of town, to develop strategies to permanently bring back Comanche Springs. They factored in the science, policy, and economics of a constant spring flow and came up with a plan.

Texas Water Trade is launching a pilot program, hopefully later this year, to put a theory to test. The idea is to pay landowners collectively up to $1 million to suspend pumping a designated amount of groundwater for a year, calculated to be enough for Comanche Springs to theoretically maintain a healthy year-round flow that would fill the pool, the canals, and Comanche Creek. The Fort Stockton Convention and Visitor’s Bureau has ponied up $50,000 for the program. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Cynthia and George Mitchell Foundation awarded a grant of $100,000.

The expected economic benefit of Comanche Springs flowing year-round is considerable. The spring-fed pool at Balmorhea State Park, 60 miles west of Fort Stockton, had a direct annual economic impact of at least $4 million on the town of Balmorhea, 5 miles east, according to a 2014 study. Fort Stockton already has an extensive visitor infrastructure in terms of motels and restaurants. All it likely needs is Comanche Springs again.

Leurig is confident that irrigation farmers can compromise with visitors and locals in pursuit of recreation. “We’re not saying we want to stop pumping,” Leurig said. “Farmers can choose to continue producing, or be part of this community-wide restoration.”

What Leurig and Mace are saying is, what was taken away can be brought back with scientific knowledge and human want-to. The springs of the Spring City of Texas can flow again, and canals and creeks can come back to life, with community consensus. That sweet summer relief that only cool, fresh artesian spring water can offer is not a mirage.

Courtesy Robert Mace