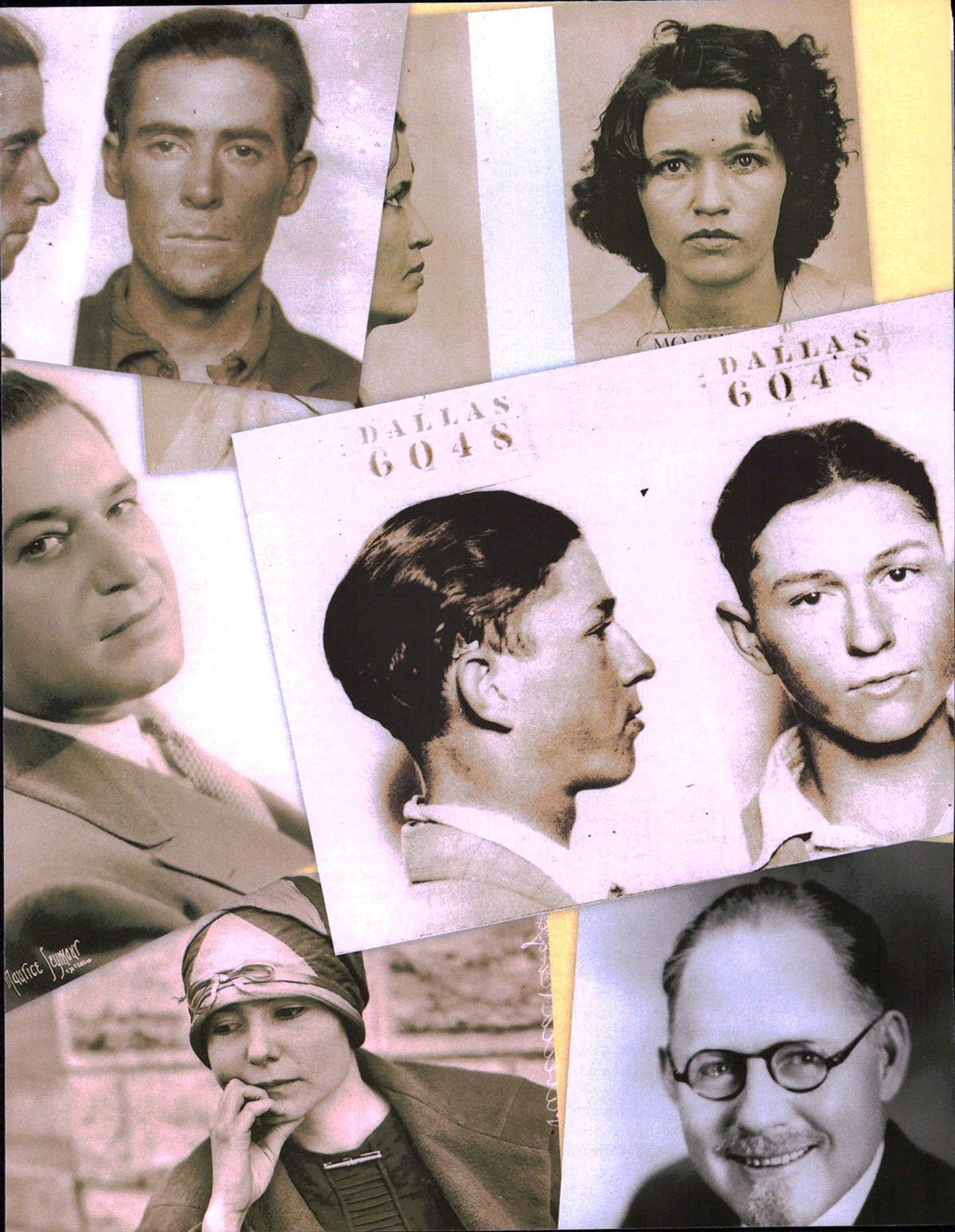

Photos (clockwise from top): courtesy Dallas History and Archives Division. Dallas Public Library (first three images); courtesy Whitehead Memorial Museum, Del Rio; San Antonio Light Collection, UTSA Libraries Special Collections; courtesy Rosenberg Library, Galveston

Imagine a Texas where air conditioning is unknown, where tiny banks operate in almost every little town, where liquor comes from bootleggers, and where the likes of Clyde Barrow and Joe Newton careen in old-time cars down unpaved roads. Welcome to a Gangster Tour of Texas.

It makes sense to begin in 1918, when the Texas Legislature voted to prohibit the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages in the Lone Star State, more than a year ahead of national prohibition. This act suddenly turned law-abiding Texans who had brewed beer or tended bar into criminals if they continued their trade on the sly. About the same time, the United States entered two decades of an epidemic of bank robbery. The crime wave grew so great that the Texas Bankers Association in 1927 offered a $5,000 reward for dead bank robbers.

Even though Prohibition ended in 1933, crime did not. Texas abounded with illegal casinos, while crime bosses and gangsters roamed … committing robberies and kidnapping the wealthy for ransom. Embezzlers secretly withdrew money from financial institutions, and some elected officials freely took bribes. In 1957, Texas Rangers closed the most famous of all the illegal Texas casinos, those in Galveston, concluding what people popularly view as the “gangster era” in Texas.

Bonnie & Clyde

Among the best known of the criminal enterprises in Texas was the group known as the Barrow Gang. The only two individuals continuously associated with the group were Bonnie Parker and Clyde Chestnut Barrow. Their trail of crime covered much of Texas as well as places as distant as Minnesota and Indiana.

Bonnie Parker was born in 1910 at Rowena, a small farming community in West Texas. After an abusive marriage, she ended up on her own in 1928, working waitress jobs in Dallas, including at the Hargraves Café.

Clyde was born in 1909 on a farm near Telico, in Ellis County. His family moved to Dallas in 1922. He went to school for a time but then dropped out The slight young man with boyish looks went to work for a series of businesses, and then began stealing cars and burglarizing houses to get extra money.

In January 1930, Clyde called at the West Dallas home of Clarence Clay, whose daughter had been in an accident. There, be met Bonnie Parker, who had come to see the friend as well. Clyde fell for the petite café waitress with blue eyes and reddish-blond hair.

In February 1930, police awakened Clyde at Bonnie’s house and arrested him for a burglary in Denton. There was insufficient evidence to convict Clyde, but authorities transferred him to Waco, where he had been charged with burglary and auto theft. Hoping to dodge the prison term, Clyde persuaded Bonnie to smuggle a pistol to him in jail. Barrow and two other prisoners escaped, but freedom was brief; the three surrendered to police in Middletown, Ohio, a week later.

While Bonnie wrote imprisoned Clyde a steady stream of letters, his mother worked for his early release. In 1932, Governor Miriam Ferguson granted him a conditional parole. Clyde returned to his family and Bonnie in Dallas.

Soon, Clyde went back to what he knew well-burglary. Over the next two years, Clyde’s crime sprees continued and progressed [with Bonnie and various other accomplices, including brother Buck and Buck’s wife Blanche]. Many people up to that time had viewed them as Robin Hood-like characters who stole from the rich and shared with the poor. But after they murdered two motorcycle officers who still had their guns holstered, people realized that the members of the Barrow Gang were cold-blooded killers. The editor of The Dallas Morning News declared, “The fugitive Barrow and his companions are … like the mad dog[;] the only remedy for their ailment is extinction. They must be hunted up and disposed of.”

Unknown to the public, professional man-hunters were already on their trail. Former Texas Ranger Frank Hamer was commissioned to track down Clyde Barrow. The ranger soon learned that the key to ending Barrow’s career might be accomplice Henry Methvin.

Bonnie and Clyde were staying in an abandoned bungalow about 10 miles south of Gibsland, Louisiana Methvin’s family lived in the same general neighborhood, and a number of them had befriended the Texas desperadoes. Hamer offered a pardon for Methvin’s Texas crimes in exchange for a tip-off that would lead to the arrest or elimination of Bonnie and Clyde, and a deal was struck.

On the morning of May 23, 1934, Methvin’s father stopped his logging truck in the middle of the road leading to the hideout Removing a tire, he gave the vehicle a disabled appearance. Hidden in the roadside brush were four Texas lawmen and two members of the Bienville Parish sheriff’s department.

At about 9:10, old man Methvin and the officers heard the distant high-pitched whine of a fast-running V-8 engine. The tan-colored Ford sedan pulled into view and paused when the passengers recognized the disabled truck. Then the first of more than a hundred gunshots began striking Bonnie and Clyde’s car. The shots killed the couple almost instantly. Inside the car the lawmen found an arsenal of firearms, clothing, a pair of purple-tinted sunshades, Clyde’s saxophone, and a partially eaten sandwich in Bonnie’s lap. The Barrow Gang was no more.

Rebecca Rogers: The Flapper Bandit

Becky and Otis Rogers shortly before her trial.

Bank cashier Frank Jamison thought very little about the slight young woman, looking to be only seventeen or eighteen, who came into the Farmers’ National Bank in Buda in December 1926. She said that she worked as a reporter for the Beaumont Enterprise, and she spent the morning talking to local farmers about cotton crops and government policies, jotting down their comments in a loose-leaf binder. Politely she had asked permission to use a typewriter inside the tellers’ cages. As lunchtime approached, Jamison stepped inside the walk-in vault for something. “As I came out she was standing five or six steps away with a gun pointed at me,” he said. Within a week, newspapers across the nation were describing the thief, Rebecca Bradley Rogers, as the Flapper Bandit. During the 1920s, “flapper” referred to a young woman who showed disdain for conventional dress and behavior.

Rebecca was born in Texarkana, Arkansas, in 1905. She moved with her parents to Fort Worth and attended Central High School, where she met Otis Rogers. Upon graduation they both went to the University of Texas in Austin, and married secretly at the courthouse in Georgetown in 1925.

Rebecca Bradley Rogers worked toward a bachelor’s degree in history, managing to pay her tuition, fees, and living expenses. Things appeared to be going smoothly until her mother lost her job and moved to Austin to live with her, placing additional strain on her daughter’s resources.

Secret husband Otis Rogers had no means with which to assist her, for he was completing his own studies and then attempting to establish a legal practice in Amarillo. The newspapers at the time were filled with reports of the epidemic of bank robbery plaguing the country, so Rebecca decided that she, too, would take some money from a bank.

The historic Farmers’ National Bank building in Buda robbed by Rebecca Rogers on December 11, 1926.

After a failed attempt to rob the Farmers’ State Bank in Round Rock (which included setting a nearby vacant home on fire to distract employees), Rebecca headed back to Austin, then south to Buda. She spotted the cream-colored brick Farmers’ National Bank, and adopted her reporter persona.

Ordering employees Frank Jamison and J.R Howe at gunpoint to open the safe inside the bank vault, Rebecca helped herself to about a thousand dollars. Locking the men inside the vault, she headed into Austin. Her only problem was getting stuck on a muddy road and having to ask a farmer to pull her out.

Rebecca took her car to a local garage to have the mud washed off. It was there, at the corner of Fifth and Brazos streets, that a police officer spotted the vehicle. Three officers waited to arrest Rebecca when she returned to pick up the car.

Rebecca was tried four times for either arson or armed robbery and in the end, Williamson County authorities quashed the arson charges, while Hays County officials dismissed the robbery charges (the day before she bore her first child with Otis). Rebecca Rogers was a free woman.

Sheriff George M. Allen reported that after he and Rebecca passed through Buda on the way to the county jail in San Marcos, “She burst out laughing and said, ‘I have a whole lot to live down, but not as much as those men back there who let a little girl hold them up with an empty gun.”‘

The Newton Boys: Four Brothers in Crime

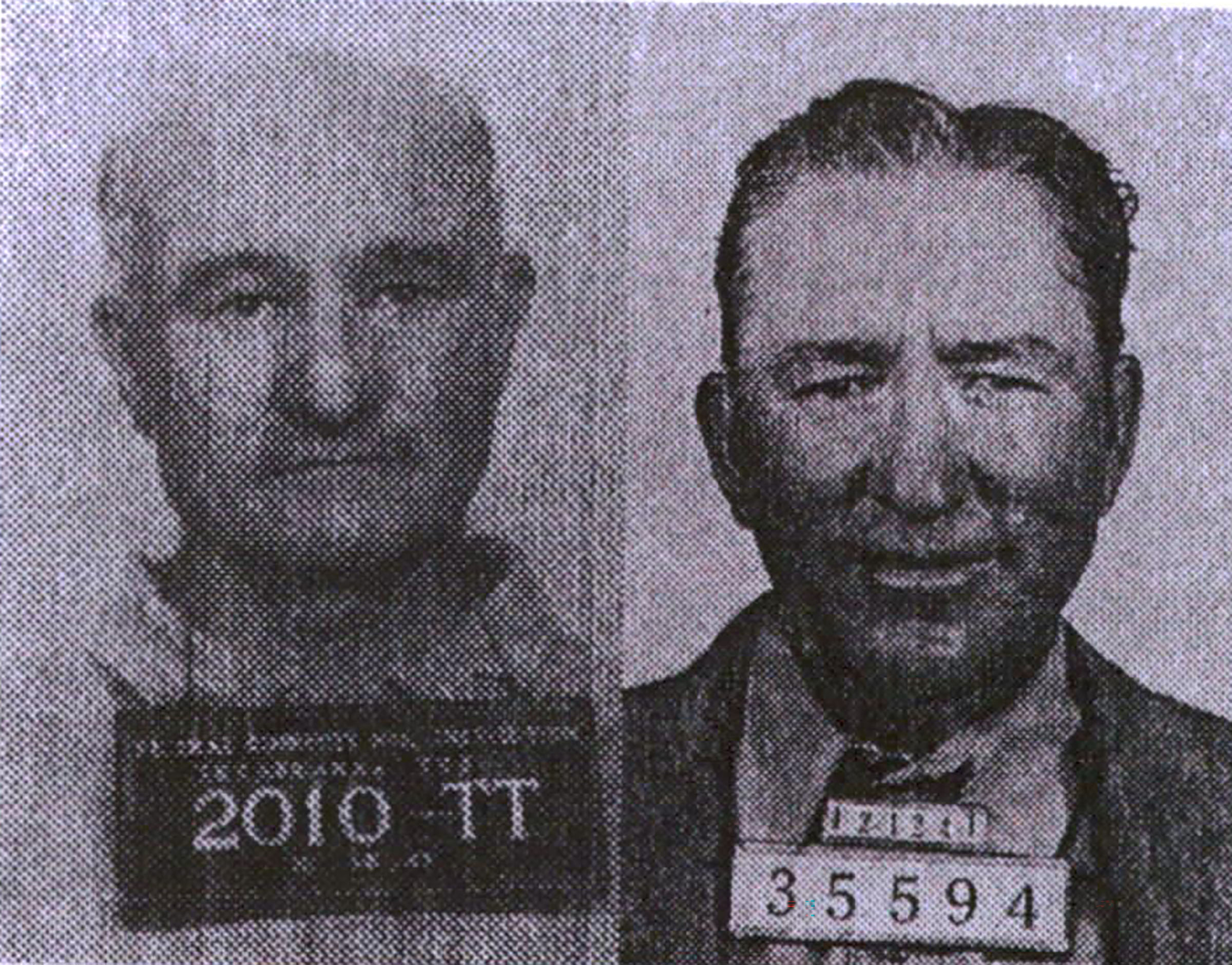

Willis Newton (left) and Joe Newton

Growing up in rural West Texas during the early twentieth century, the four sons of Jim and Janetta Newton would have been expected to grow up to be cotton farmers or cattle ranchers. Instead, they became one of the most successful teams of professional bank and express-car robbers in the United States. Resembling railway baggage cars, express cars transported high-value freight and usually had armed guards. The Newton Boys’ career ended in 1924 with a spectacular express-car heist in Illinois that netted them an unbelievable three million dollars but ended with arrests and imprisonment.

Willis Newton had several early encounters with the law, and while incarcerated, he learned the fine art of blowing open safes with nitroglycerine. Once freed in 1919, he recruited his brothers Jess, Joe, and Doc to join in what became a family enterprise.

For the first two years, the gang typically undertook night burglaries

of small-town banks. During the summertime, they traveled across the Great Plains and Midwest, sometimes crossing into Canada, casing potential banks. Willis claimed that it took only about five minutes to pour liquid nitro around a safe door and blow it off, so a carefully planned nighttime burglary required only about 15 minutes.

After doing their work, the four brothers typically returned to Texas to enjoy the proceeds of their efforts. After a profitable season in burglary, Willis remembered, ”We come on down to San Antone for the winter, where we stayed at the St. Anthony Hotel most of the time.”

The Hondo State Bank as it appeared about the time it was robbed

Even though the Newton Boys operated mostly outside the Lone Star State, occasionally they took advantage of opportunities closer to home. The first known Texas bank that they burglarized as a group was the Boerne State Bank, 30 miles north of San Antonio. The next Texas ”bank job” was in the town of Hondo, where they broke into two the same night, having discovered that they didn’t have quite enough money to maintain the lifestyle they liked.

On August 25, 1921, the Newton Boys undertook the first of two unsuccessful late summer train heists in Texas, planning the first-in Grayson County to coincide with a registered mail shipment of bank notes from the Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas. Finding only ordinary registered mail, the Newton Boys planned a follow-up job on a train between Bloomburg and Texarkana. ”We want that black box containing money shipped from Shreveport,” barked one of the robbers. To their dismay, the box was not there. Years later, Willis grumbled, ”We got a pretty good bunch of bonds and stuff, but we missed that box.”

The Newton brothers went on to rob banks in New Braunfels and San Marcos before committing the 1924 Illinois robbery that would take them to the Leavenworth federal penitentiary. On release, they eventually returned to Uvalde, where they resided for the remainder of their lives. ”Robbing banks is hard work,” Willis reflected late in his life. “There’s no fun to it I never done it for the excitement I done it only for the money.”

Dr. John L. Brinkley

Portrait of Dr. Brinkley

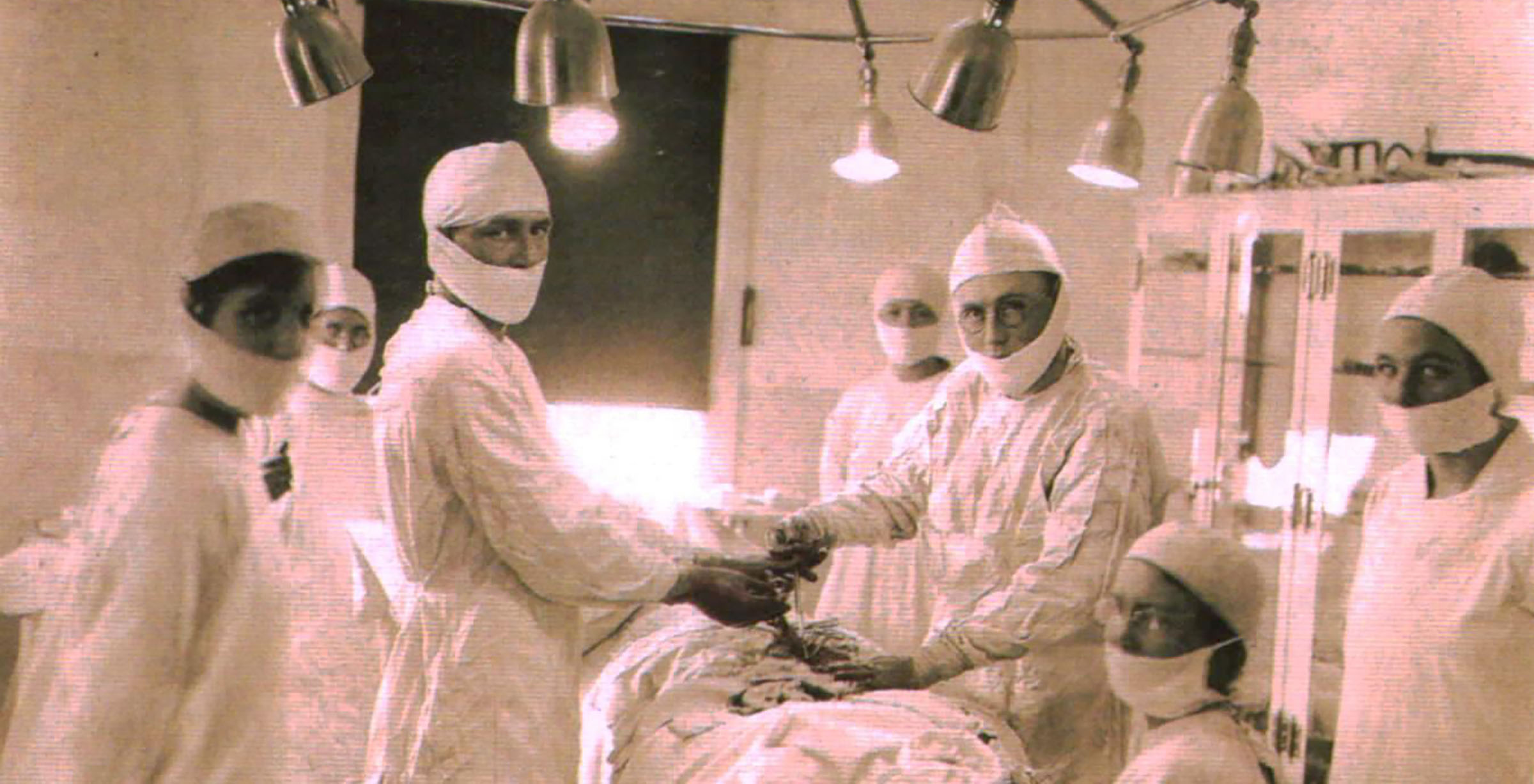

Born in North Carolina in 1885, Brinkley attended a legitimate medical school in Chicago before dropping out and “finishing” his degree at the Eclectic Medical School of Kansas City. In 1917, he settled in the town of Milford; after a few months, a young farmer came to Dr. Brinkley lamenting that he had been unable to father another child, then the conversation drifted to farming, rams, and buck goats. Brinkley reportedly joked to his patient that ”you wouldn’t have any trouble if you had a pair of those buck glands in you.” The farmer unexpectedly responded, ”Well, why don’t you put ’em in?” A year after Brinkley implanted slivers of goat testicles in his patient’s scrotum, the farmer and his wife became parents of a healthy son.

Dr. Brinkley expanded his practice to include a hospital, behind which stood

a corral filled with billy goats. He promoted his operation as curing not only male sexual dysfunction but also afflictions such as high blood pressure, epilepsy, diabetes, senility, obesity, and dementia To reach distant audiences, Brinkley secured a license for a new AM radio station, and found avid listeners for his monologues on child care, hygiene, and procreation. “All energy is sex energy,” he proclaimed.

As early as 1928, the American Medical Association began monitoring Brinkley’s activities. Two years later, the organization singled him out as “reeking with charlatanism of the crudest type.” The Federal Radio Commission chose in June 1930 not to renew Brinkley’s broadcasting license, then the Kansas Medical Board withdrew Brinkley’s license to practice medicine within the state. He began looking for new fields. He decided that if the U.S. government had taken away his radio license, he would move outside the country and beam his messages back. ”Radio waves pay no attention to lines on a map,” he quipped.

Authorities in Del Rio and Villa Acuna, across the Rio Grande, invited the flamboyant physician to relocate, with the Mexicans offering a 10-acre site for a broadcasting station at no cost.

Dr. Brinkley made the six-story, airconditioned Roswell Hotel his Del Rio medical headquarters. In addition to attracting patients to the hospital, Brinkley and his advertisers used the broadcasts to sell everything from tomato plants to Last Supper tablecloths.

Dr. Brinkley standing to the right of a patient.

Brinkley’s broadcasting power grew in stages until late 1935, when XERA’s strength reached an incredible 1 million watts. Brinkley’s on-air lectures on bloating, fistulae, and enlarged prostates could be heard all across the Great Plains to Canada and at times on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

When the end came for Dr. Brinkley, it came quickly. In 1941, Brinkley declared bankruptcy, a newly elected Mexican president expropriated station XERA, and Brinkley developed a blood clot in his left leg, which led to gangrene and the removal of the limb. While he convalesced, federal marshals served Brinkley with a warrant charging him with mail fraud. He never went to trial. On May 26, 1942, the old goat gland doctor met his Maker.

The Maceo Brothers

Galveston became the largest city in Texas between 1830 and 1860, when shippers exported more cotton from its wharves than from any other American port. Italian brothers Rosario “Rose” Maceo and Salvatore “Sam” Maceo in time brought big-time gaming to the port city.

The brothers worked as barbers upon arriving in Galveston in 1910, but after prohibition began in Texas in 1918, the Maceos entered bootlegging, eventually gaining near-complete control of the illegal alcohol trade in the city. By this time, Galveston was attracting large numbers of tourists from the mainland, and in 1926 they built the Hollywood Dinner Club, a nightspot that boasted dining rooms, a ballroom, and areas where guests could wager at craps, blackjack, roulette, and other games.

Next, at 2216 Market Street, they erected the three-story Turf Athletic Club. Guests entered through a groundfloor restaurant, then took the elevator upstairs to the casino area, as well as to private gaming chambers.

The Hotel Galvez

Of all the Maceo enterprises, the beachfront Balinese Room, on a pier over the waters of the Gulf of Mexico across from the Hotel Galvez, was the most famous. The brothers’ business strategy was to attract well-heeled gamblers with elaborate meals combined with lavish floor shows. Among the nationally known performers who frequented the Balinese stage were Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and Bob Hope. “The atmosphere was so friendly,” reminisced one former customer, “that you almost enjoyed losing your money there.”

The Maceos also operated thousands of slot machines in store and restaurants throughout the island. Mike Gaido of Gaido’s seafood restaurant once quipped, “The Maceos didn’t ask if you wanted their slots; they just asked how many.”

From time to time, locals and outsiders encouraged officials to “clean up” the town, but then the reform spirit passed. In June 1951, Price Daniel, the Texas attorney general, used state court injunctions to end walk-in casino gambling. Slot machines disappeared from public places, while gaming houses like the Balinese Room became “private clubs.”

Lawmen breaking up illegal slot machines.

In 1956, local attorney Jim Simpson and newly elected Texas attorney general Will Wilson recruited undercover investigators to gamble in Galveston, then prepare detailed notes about their experiences. On June 10, 1957, Simpson called for the gambling houses to cease operations. A week later, Texas Rangers began removing illegal equipment and destroying it.

Even without the court injunctions and raids, the Gulf Coast gambling operations faced doom. By then, legal high-stakes gambling in Las Vegas drew gamers from throughout the United States, and Las Vegas thus superseded Galveston as America’s “Sin City.”