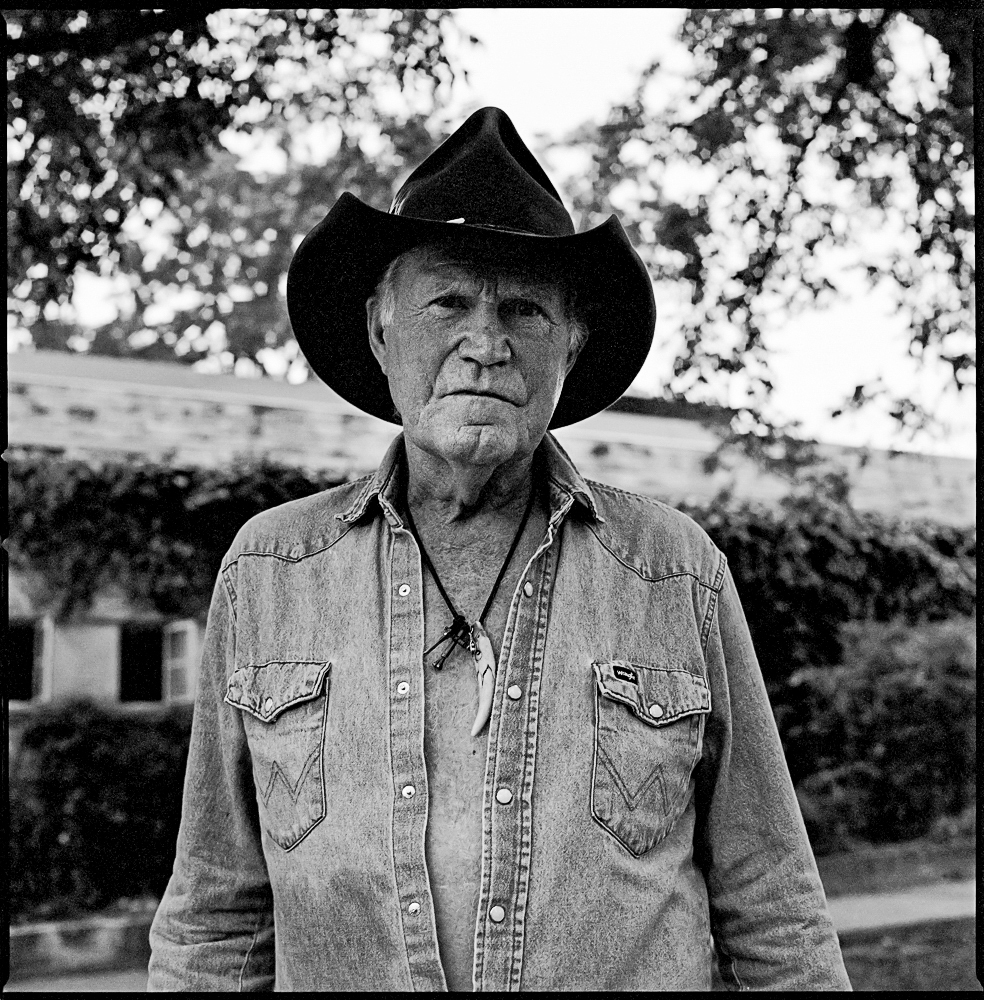

Billy Joe Shaver at Barton Springs Pool in Austin in 2012. Photo by Sandy Carson.

Outlaw Country pioneer Billy Joe Shaver died Wednesday in Waco after suffering a stroke. The poet in the blue work shirt, considered “a honky tonk Hemingway,” was 81.

“The devil made me do it the first time / The second time I done it on my own,” was his most memorable line (from the 1973 song “Black Rose”), but so many great lyrics sprung from the former La Vega High student. Everyone called him Bubba, but when he wrote beautiful poems for the Waco school’s paper, he signed them “Billy Joe Shaver” as a disguise so the fellas wouldn’t tease him. Still, Shaver never backed off from his calling: His resume includes “Old Chunk of Coal,” a top 5 hit for John Anderson, “Good Christian Soldier,” “Georgia On a Fast Train,” “Ride Me Down Easy,” “Live Forever,” and 10 songs on Waylon Jennings’ classic Honky Tonk Heroes LP

“I always thought I’d be the first to go,” Shaver said in 2002, following the deaths of his mother, Victory, ex-wife, Brenda (who he married three times), and guitarist son, Eddy, in a span of less than two years. In spite of his grief, Shaver packed in almost 20 more years of performing before declining health sidelined him in recent months.

The man Willie Nelson has called the best songwriter in Texas once faced a prison sentence in 2007 after shooting a man outside a bar near Waco. The jury believed Shaver’s self-defense claim and found him not guilty. Sitting behind him in the courtroom was his good friend and fan Robert Duvall, who got Shaver a role in the 1998 Oscar-nominated film The Apostle.

Shaver’s early life was one of bare feet, bare knuckles, and bared soul. His father bailed on him before he was born, and with his mother having to work two jobs, baby Shaver and his older sister were raised by their grandmother in Corsicana. “She gave us reality,” Shaver recalled. “Our grandmother told us straight out that there wasn’t no Santa Claus, but just play along with the other kids. Unless the Salvation Army dropped off something, we didn’t get no Christmas presents.”

When a 10-year-old Shaver snuck off to see comic hillbillies Homer and Jethro, as well as a little-known opening act named Hank Williams (an experience recounted in the song, “Tramp On Your Street”), his grandma was waiting up with a switch in her hand. “I think the reason I remember that show so well was because of the whippin’ I got,” he recalled.

When his grandmother died, Shaver, then 12, moved to Waco to live with his mother, who worked as a waitress at a honky-tonk called Green Gables. Shaver immediately felt at home in a roadhouse that smelled of beer and smoke, where the jukebox always seemed to play Lefty Frizzell when he walked in.

But Shaver clashed with his stepfather and often took off on freight trains or rode his thumb right out of Waco. When he turned 17, his mother signed the papers for him to join the Navy. “I was glad to go, and they were glad to see me go,” he said.

To know Shaver and not have a story to tell is like coming home from a Willie Nelson Picnic without a sunburn. There are famous stories, like how he lost three fingers at the knuckle on his right hand in a sawmill accident at Cameron Mills when he was 22. Shaver had read an article about how a man in Asia had his severed fingers reattached, so in the midst of great pain he gathered up his three lopped digits. “The doctor said he couldn’t do anything for me,” Shaver said. “I told him that in Japan they just sewed somebody’s fingers back together, and he said, ‘Well, this ain’t Japan.'” He returned to work with his hands bandaged and his fingers in a jar. When a woman at the mill asked for his fingers for some sort of voodoo ritual, he gave them to her.

There’s also the one about the time he spent six months in Nashville tracking down Waylon Jennings, who had promised to do an entire album of Shaver songs after hearing “Willie the Wandering Gypsy and Me” during an impromptu guitar pull in a trailer backstage at the infamous Dripping Springs Reunion show in 1972. “Waylon asked me if I had any more of them ol’ cowboy songs, and I said I had a whole sack full of ’em,” Shaver said. But afterward, Jennings wouldn’t return his calls.

Frustrated and broke, Shaver finally found Jennings in the hall of a recording studio late at night. “I told him that if he didn’t make good on his promise to record my songs, I’d whip his ass right there. I was so [angry] I didn’t even notice these two big biker bodyguards at his side.” Before the two could pounce on Shaver, Jennings raised a halting hand and sat down with the fuming songwriter to talk about the album.

When Jennings recorded Honky Tonk Heroes in 1973, he broke so many rules the album turned into the opening salvo of the Outlaw Country movement. Besides playing 10 tracks by an unproven songwriter, Jennings insisted on using his own touring band in the studio. The result was a record that holds up like Creedence Clearwater Revival, riding a great groove on the title track and “Black Rose” and then taking a touching turn on “You Asked Me To,” Shaver’s best love song to Brenda.

Shaver’s songs are so much a part of him that he has never recorded another writer’s material except on tribute albums to his hero Merle Haggard and good friend Townes Van Zandt. “Brenda hated Townes with a passion,” Shaver once said, with a laugh. “She knew he was trouble.” But Brenda’s protective instincts hurt her husband’s career when she talked him out of being the fourth act on Wanted: The Outlaws, with Waylon and Willie and Jessi Colter. Shaver was replaced by Tompall Glaser on the first country album to sell a million copies in 1976.

Shaver earned the unofficial nod as the musical poet laureate of the Songwriter State, not just because he had the ability, like Springsteen or Prine, to nail an entire set of emotions and circumstances with a single line, but also because in his lyrics you can hear music. The rhythm of his words is all the beat you need, as witnessed by this classic chorus: “I been to Georgia on a fast train, honey / I wudn’t born no yesterday / Got a good Christian raisin’ and an eighth-grade education / Ain’t no need in y’all treatin’ me this way.”

His former drummer Freddy Fletcher, whose mother, Bobbie Nelson, is Willie’s sister, said in 2002 that the deeply religious Shaver seemed to have an angel on his shoulder. “We’d find ourselves in terrible predicaments out on the road, but somehow Billy Joe would find a way out of it.” One night in Baton Rouge, in the heat of the urban cowboy trend, Shaver baited the audience waiting for him to get offstage so they could dance to Johnny Lee.

“Billy Joe announced, ‘There ain’t a cowboy among the whole bunch of ya. Y’all look silly with your feathers in your hats,’” Fletcher recalled. A few roughnecks had to be held back by their buddies after the set, but Shaver and the boys were soon on the road to the next adventure.

Sometimes his angel was Willie Nelson. After Shaver got sober and moved back to Houston in the late ’70s, away from his demons in Nashville, he barely supported his family with royalty checks. He thought he was washed up, but one day he got a call out of the blue that would put him back on track. It was Nelson, whom he’d known since the late ’50s honky-tonk circuit in Central Texas. Nelson and Emmylou Harris were about to start a tour of arenas and, although there wasn’t time to put his name on the bill, Shaver could open the shows and make a few hundred bucks a night. “I can’t tell you all the times Willie’s bailed me out of situations, but that was a big ‘un,” Shaver said. “I wasn’t sure if I’d ever get up on a stage again.”

In the late ’90s, Bob Dylan recorded “Old Five and Dimers (Like Me),” but when it came out on the soundtrack for Hearts of Fire, the song was credited as a traditional folk song. “At first I was [angry],” Shaver said, “but the more I thought about it, I took it as a compliment. Every writer wants to write something that’ll last long enough to be part of the public domain.”

Shaver’s favorite song was the one he wrote with son Eddy because it told of the destiny of a simple man with a sack full of cowboy songs: “Nobody here will ever find me / But I will always be around / just like the songs I leave behind me / I’m gonna live forever now.”

This article features excerpts from Michael Corcoran’s book All Over the Map: True Heroes of Texas Music, for which the author interviewed Shaver in 2002.