The

Ties

That

Bind

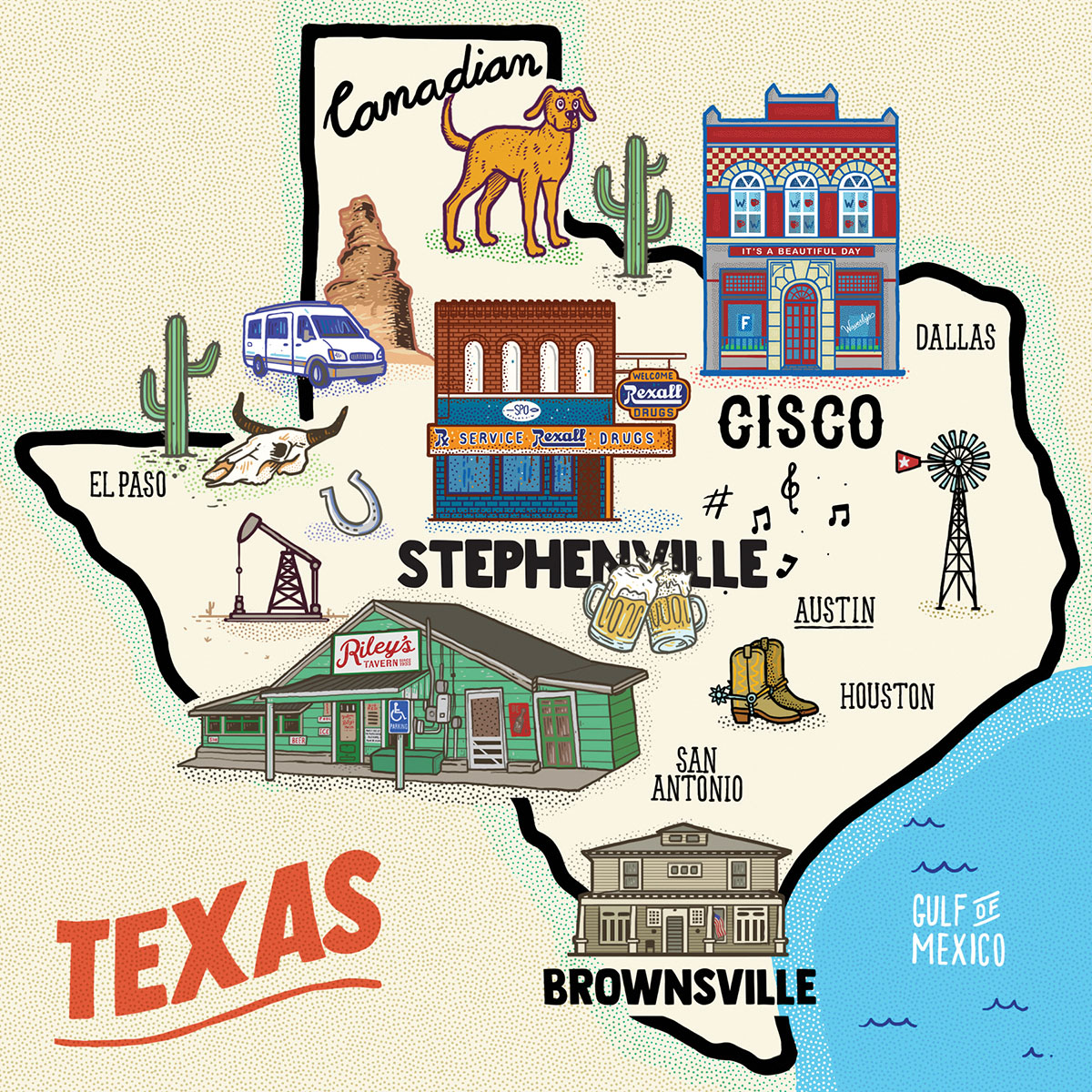

Finding unity on a road trip from the

Panhandle to the Rio Grande Valley

Writer Clayton Maxwell and her family at a Palo Duro Canyon overlook; palm trees in Brownsville.

“One and indivisible”—these two words conclude the compact 17-word ledge of Allegiance to the Texas state flag. For the last year, I’ve heard my 11-year-old son recite the pledge every morning during online school. Because most of my interactions with the rest of Texas during this pandemic have been through a laptop, those two words burrowed in and left me asking: If we are indivisible, what unites us? What common ground do I share with Texans up in the dry flatlands of the Panhandle? Or with those in the balmy valley of the Rio Grande? Sometimes finding an answer means you’ve got to turn off the laptop and drive.

On the morning of Jan. 2, my husband, son, and I borrowed a camper van from a neighbor, loaded up our dog, Jake, and headed out on a six-day expedition. With our COVID-19 face masks hanging on easy-access hooks, we set out to traverse the state from the Oklahoma border to the Gulf, exploring new places and meeting new people. On the way, we hoped to find what common ground we share with a few of the other 29 million people who call Texas home.

It was a tall order. Our state is too big and complex to condense into a simple pledge. And yet, as the van’s odometer clicked on, we met a diverse set of Texans who, despite living very different lives, all had one thing in common: a fierce dedication to their callings and communities.

After an eight-hour drive from our Austin home, we pulled into Canadian, a Panhandle town of 3,000 along the Canadian River, and checked into a revamped motel called The Last Cowboy’s Court. Our room was a warm hug for road-weary souls, with a crimson clawfoot tub, coffee from the local Brown Bag Roasters, artisan soaps, and ranching photos on the walls. My husband, Scott, in describing the boutique lodging’s refined touches, used a Spanish word—esmero, which translates to “care.” But esmero means more than care; it comes from the heart. As a Spanish professor described it to me: “Someone doing something with esmero shows a deep love for what she does, as if doing it gave sense to everything in the life of this person.” And, we were soon to find out, there’s plenty of esmero here—not just at The Last Cowboy’s Court, but throughout Canadian.

The next morning we met Tiffani Kirkland, a waitress at The Canadian Restaurant. Wearing a trucker’s hat with the words “Red Dirt” stitched on the front, Kirkland not only knew the names of almost every customer who walked in, she also knew their orders from the menu of classics like omelets and steaks. With country music playing in the background, Kirkland refilled our coffee and told us how the town made it through 2020.

“We helped each other,” said Kirkland, who no longer works at the restaurant. “When a family had to quarantine, we brought them casseroles, or we’d pick up kids from school. Canadian’s a close-knit community. We’ve known each other most of our lives, and our parents have, too.”

As the oil industry here dried up—a consequence of geopolitics, oversupply, and reduced demand during the pandemic—Kirkland’s oil field customers disappeared as well. But the ranchers still came in every morning. “This is Jimmy Schafer,” she said, pointing to a photo on the wall of a man in a white cowboy hat staring into the eyes of a Longhorn. “He just randomly shows up and hangs his pictures on the wall. He is 91 and comes in every day. If he misses a day, we call.”

Illustration by José Saccone

A day ago Canadian was a dot on my computer screen; now it was real faces and the biggest pancakes my son, Harry, had ever seen. Our next stop was the office of The Canadian Record, where we met Laurie Ezzell Brown, the Record’s editor and publisher since she and her mother took over from her late father in 1993. Brown explained how the oil slump and closures from the coronavirus have put Canadian in a precarious place. “Every week we hear about a business closing, a business laying off their employees, a business relocating,” Brown said.

But Canadian and surrounding Hemphill County have a long history of challenges. In 2017, a megafire swept across this part of the Panhandle, killing cattle and turning the land black. People came from across Texas and beyond, hauling hay and water for surviving livestock, along with fencing materials to help ranchers rebuild.

“It was staggering, the damage. But we rebounded tremendously,” Brown said. “When you’re fighting the pandemic, when you’re fighting wildfires, when you’re fighting all the things that are affecting us right now, the question is, how are we going to get through this together? Nine-tenths of the people who come through the door of the newspaper say, ‘I don’t always agree with you, but you sure put out a great newspaper.’ It is possible for us to have different viewpoints and still get along. Actually, in a town like this, it’s essential.”

We hit the road again to meet John Erickson, whose series of Hank the Cowdog books are loved around the globe. On the drive to Erickson’s ranch, about 45 minutes from Canadian, Harry read Hank stories out loud, switching voices from Hank to Drover, his sidekick, to Pete the Barn Cat. The dirt road to Erickson’s house—Hank’s Road—leaves the flatlands behind as it dips down into a scarlet canyon.

Kris, John’s wife of 53 years, greeted us in front of the new house they’d just finished building after their previous home burned in the 2017 fire. As we talked in the spacious new living room with unobstructed views of the blue sky and red caprock, I saw how much Erickson loves this land.

“It’s a beautiful piece of God’s creation, and it nourishes my spirit every day,” said Erickson, who grew up in nearby Perryton. “I put myself in the position to be the medium that pulls thoughts, emotions, symbols, mythology—whatever it is—out of the atmosphere and put it into a form that brings delight to families. I really don’t know how that happens.”

Erickson writes every morning without fail, pursuing his craft with a devotion that goes back to the biblical stories his mother told him as a young boy. “Art should make people laugh or cry or come to a deeper appreciation of who they are in this infinite universe that we occupy,” he said. “It should aspire to the same standards that the lady in Perryton who makes hot tamales for my wife adheres

to, which is you must make your customer better. It’s a relationship of trust.”

Esmero, it seems, manifests in both writing and hot tamales.

Too soon, we said our goodbyes and headed for Palo Duro Canyon State Park, our destination for the night. We traced the Canadian River east and skirted Amarillo before arriving just as the sky turned rosy with sunset. After crossing so much tortilla-flat land, we were stunned to find ourselves on the edge of this geologic wonder, to witness its dramatic red and orange valley, its rocky buttes and mesas. The metaphor was inescapable; it’s what our trip had been so far. A part of Texas that had seemed flat to me—just because I didn’t know it—had surprised me with depth and beauty. It just took spending some time here.

Cisco

The next morning, we packed up camp, took a short hike to warm up after the 17-degree night, and departed for Cisco, where I’d heard about a shop that serves a very good cup of coffee. The five-hour drive started with a dusty grind down Interstate 27 to Lubbock, then veered east through arid hills, pastureland, and wind farms toward Abilene. Our road fatigue lifted the moment we arrived in Cisco and walked into Waverly’s Coffee and Gifts, with its high ceilings, book-lined walls, and aroma of coffee. The creation of Sean King, a writer, minister, and barista, Waverly’s overturned my ignorant assumption that you can’t find good coffee in tiny towns. King makes each cup on the spot in a French press. One sip paired with a bite of maple pecan strudel, and I could taste just how wrong I’d been. It was delicious esmero.

We hung out in the sun-filled art room, adjacent to the café, where King’s wife, Kasity, hosts occasional art workshops and the couple homeschool their kids. King said he’s taken on yard work and sculpting to make extra money during the pandemic. His sense of purpose—as a minister, father, and small business owner—was moving. I asked him how people were getting along in Cisco.

“In our small community, you just have to get to know people,” he said. “And when you get to know them, you sharpen each other, you connect as humans. That’s what this coffee shop has been—a cultural crossroads where a lawnmower man can sit down with a millionaire, or an atheist can sit down with a Christian and have a conversation.”

Stephenville

High on caffeine and good conversation, we piled back in the van for an hourlong jaunt southeast on Interstate 20 and Ranch Road 2214 through subtle green hills to Stephenville. We wanted to check in with Jahmicah Dawes, the proprietor of one of the only Black-owned outdoors shops in the country. Slim Pickins Outfitters sits in a spruced up Rexall Pharmacy storefront on the town square; its motto is “Act Justly, Love Kindly, Serve Humbly.”

Just like others we’d met on our trip, Dawes has struggled to keep his business afloat this past year. But his dedication to his mission has kept him going. Along with building his online sales, he’s established strategic partnerships with groups like Black Outside, a San Antonio nonprofit that engages Black youth with the outdoors.

“For the longest time,” he said, “you’ve had people of color being stewards of the land and being told ‘it’s not yours.’ But the first African Americans grew up on the land. I want to help people reconnect. I want to build this so our kids will feel safe, both in the world and in the outdoors.”

Mid-conversation, Dawes saw the Stephenville police chief walking by and dashed out to the sidewalk to talk with him. Since last June, Dawes and Chief Dan Harris, whom Dawes calls “Chief,” have been meeting monthly with a small group of police officers and community leaders of color to “break bread” and better understand each other.

“We clear off the table, sit down with some pizza, and talk—and, well, it’s been phenomenal,” reflected Harris, who’s been an officer for over 30 years. “We respect each other and love each other.”

Hunter

Since our goal for the day was to make it to the Hill Country, we said goodbye to Dawes and steered the van south on US highways 281 and 183 as soft hills gave way to the spreading megalopolis of Austin, then Interstate 35, then San Marcos. We turned southwest into the choppy topography of the Edwards Plateau and reached Hunter, a backroads town where Joel and Angie Hofmann run Riley’s Tavern. The historic dive bar dates to 1933, when 17-year-old J.C. Riley hightailed it up to the State Capitol in a Model T to nab the first beer license granted to a Texas bar after Prohibition.

Relieved to trade in the steering wheel for a cold beer, we rested our bones at a picnic table on the back patio. Joel, who bought Riley’s in 2004, told us about the regulars who’ve stuck by them during the pandemic, some of whom grew up coming to the tavern. “The whole pandemic was really hard on the bartenders more than anything,” Angie added. “A lot of our regulars—people with different thoughts and views—pitched in and donated money. Some of them don’t even like each other, but they still came together.”

A shared love for a historic honkytonk—now that is something Texans can rally around.

Brownsville

We slept hard that night in one of the two cottages Hofmann rents out next door to Riley’s and woke to our final southbound stretch: Interstate 37 and US 77 to Brownsville. For four hours we drove through expansive brushlands, passing towns such as Three Rivers, Kingsville, and Sarita, before pulling into a palm-lined neighborhood on the edge of Brownsville’s downtown. Mariachi music played through open windows, and the air was sultry. We’d come a long way from our finger-numbing 17-degree mornings in the Panhandle.

Our first stop was the 1909 Hicks-Gregg House, a stately two-story home restored by Javier Salinas as a vacation rental. The home’s expansive porch looks across three plant-filled lots close to Brownsville’s downtown. In the bright sunroom, Salinas cranked up the player piano for us and spoke about what brings people together in Brownsville.

Chef Christian Nevarez of Terras Urban Mexican Kitchen

“Historic preservation is important in Brownsville right now,” Salinas said. “There is a curiosity that comes with seeing how we are bringing a building back to its natural glory. We also have young people establishing restaurants and bars. You can’t help but want to get behind them as well. This young entrepreneurial spirit mixed with historical preservation—it’s a winning combination.”

That night, we tasted the truth of Salinas’ words at Terras Urban Mexican Kitchen, a hip eatery in the heart of downtown. Opened originally in 2016 by two friends, Christian Nevarez and Juan Flores, Terras expanded and reopened in 2020. With original brick walls, exposed beams, and sophisticated Mexican food, Terras would fit in with the trendiest restaurants of Mexico City.

We took in the scene as we dipped hot tortilla chips into the shrimp molcajete, a concoction of fresh-caught shrimp in a tangy sauce with squares of panela cheese. Even with the socially distanced tables, lively conversations flowed from Spanish to English, filling the room. Amid a pandemic and economic hardship, there was still joy here.

The next morning over coffee, Nevarez and I talked about his hunger to start his own restaurant, his experience as a first-generation Mexican American, and how his mom, Sylvia, grew up in Matamoros and now proudly makes the “Mom’s Cornbread” on the menu. Nevarez is a self-taught chef, but “always reading, trying to learn as much as possible about the science of food.” When he explained the shrimp molcajete to me—how he roasts the tomatoes and blends them with the dried chipotle—the detail and passion with which he spoke was like poetry… or esmero.

As we visited, an image of Erickson back on his Panhandle ranch flashed through my mind. In fact, I saw every person we’d met on this sojourn, going back to that first morning in Canadian with Kirkland in her “Red Dirt” hat.

Later that day, road-spent but exhilarated, we plopped down in the sand at Isla Blanca Park on South Padre Island. Feeling the warmth of the winter sunshine, we were revived by the revelations of our 1,500-mile journey. From our room at The Last Cowboy’s Court to this beach, esmero had reigned.

“One and indivisible,” as the Texas pledge states, is perhaps an unattainable ideal. But we found a powerful unifying thread linking each of the Texans we were lucky enough to meet. Its fibers are reverence and hard work. With their different stories, politics, skin colors, and surroundings, these Texans share a whole-hearted devotion to their callings and neighbors. After a year spent at home, distracted by a pandemic and consumed with our own troubles, meeting them lifted us up. Out on the road again, mingling safely with life-and-blood humans and not just a computer screen, we witnessed the inherent goodness in people. We may not be “one and indivisible,” but we’re also not as different as we might think.

Can’t-Miss Stops Along the Route

Canadian

Brown Bag Roasters: Coffee and community next door to The Canadian Record newspaper. brownbagroasters.com

The Last Cowboy’s Court: One of Texas’ coziest motels. lastcowboyscourt.com

Cisco

Waverly’s Coffee and Gifts: A welcoming spot for coffee and pastries, as well as a fine selection of books and children’s toys. waverlystexas.com

Stephenville

Slim Pickins Outfitters: A fun, friendly outdoor gear shop on the square. slimpickinsoutfitters.com

Hunter

Riley’s Tavern: A historic bar for live music and beer on an outdoor patio, located on the backroads west of I-35. rileystavern.com

Brownsville

Terras Urban Mexican Kitchen: Chic eatery in historic downtown. terrasurbankitchen.com

For road-trip entertainment, the “Hank the Cowdog” podcast featuring Matthew McConaughey as Hank is a sure family pleaser. hankthecowdogpodcast.com