East Texas

Exploring the life

of Texas' first national hero —

The man and the myth

TOP IMAGES:

The San Jacinto Monument; a portrait from about 1860 at the Sam Houston Memorial Museum

Propped against an oak tree in the Texas Army’s camp and nursing a musket-ball wound to his ankle, Houston resisted his men’s thirst for blood revenge. Though outraged over the massacre of Texas rebels in the preceding weeks at the Alamo and Goliad, Houston opted to spare Santa Anna’s life, strategically using the captive presidente to discourage a follow-up attack by Mexican reinforcements and secure Texas’ independence. A marble memorial and spindly oak mark the events of April 22, 1836, but the actual tree is lost to history.

“This is easily one of the most important places in the history of the United States,” contends Denton Florian, executive producer and director of the documentary film Sam Houston: American Statesman, Soldier, and Pioneer. Yards away, a tanker blasts its horn and fishermen amble down to the waterfront, rods and buckets in hand. “It happened right here,” he continues. “Sam was the only one standing between Santa Anna and a blade, bullet, or rope. He had a pragmatic military reason for it, but he also said, ‘We’re better than that.’ If we wanted to be respected around the world, we had to show that we were different.”

Stories about Houston are like lumber in the framework of Texas history. Houston traversed countless miles across Texas during its construction as a state, his name listed in a roll call of pivotal moments. Few historical figures left such well-documented footsteps, and historians have followed suit with expansive biographies. Houston’s name remains ubiquitous, tagged to Texas’ largest city and every imaginable spinoff, from universities to sports teams.

But just as in Houston’s day, Texas is always changing. Demographers estimate the state’s population will grow 60 percent to 47 million people in the next 30 years, including millions of newcomers from faraway places. Every day, tiny Texans are born and wizened historians die; memories fade and buildings crumble. Collectively, what do we really know about Sam Houston?

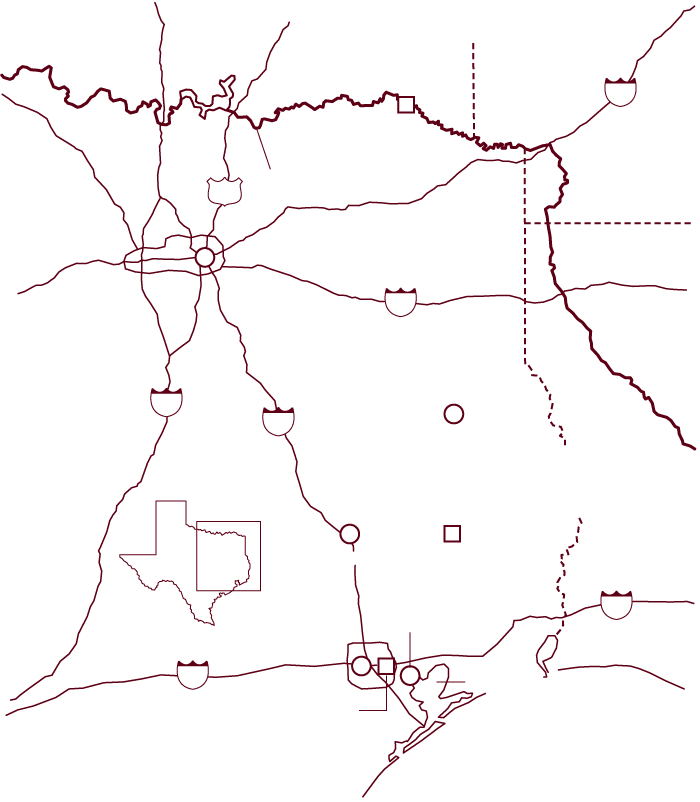

Clues to the man and the myth—Texas’ first national hero—abound in East Texas, the historical gateway to this state from the U.S. and the population base during the frontier days. From the Red River borderlands to the Piney Woods and the Gulf Coast, artifacts of Houston’s life manifest on street corners and in museums.

On The Road

Houston arrived in Texas in 1832—part ambitious settler, part political operative. Thirty-nine years old, he was already famed as a War of 1812 veteran, congressman, Tennessee governor, and protégé of President Andrew Jackson. With commanding charisma, Houston was as famous for his tribulations as his accomplishments. Back in Tennessee, his first wife, Eliza Allen, left him after only 11 weeks. For the rest of his life, Houston would never explain why. Under a cloud of shame, Houston resigned the governorship and dropped out of society. He found his way to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), where he lived with the Cherokee for three years and garnered the nickname “Big Drunk.” He ran a trading post, married a Cherokee woman named Diana Rogers for a brief time, and advocated for the Native Americans, combating corruption among government agents. That issue led to a Washington, D.C., street fight in which he beat up a congressman from Ohio. Though he was reprimanded after a trial in the U.S. House of Representatives, Houston’s spirited self-defense rekindled his political career just as Texas was bubbling with action.

Houston crossed the sandy Red River in December 1832 at Jonesborough, a town claimed by both Arkansas Territory and Mexico at the time. Historical markers on Farm-to-Market Road 410 recall the village, which in today’s terms was northeast of Paris near the State Highway 37 bridge at Albion. But Jonesborough itself washed away long ago. Cattle pastures and soybean fields blanket the bottoms down to the river, a rippled course framed by cream sandbars, bluffs of red mud, and wispy green willows.

“Sam Houston spent his first night in Texas at my ancestors’ house in Jonesborough, so the story goes,” says Jim Clark, a history buff and banker in nearby Clarksville. Jim’s great-great-great- grandparents James and Isabella Clark ran the Jonesborough ferry, and their son Pat Clark published a history of the region in 1919, North Texas, 100 Years Ago. It includes an account of Houston’s visit: “When Houston was helped to venison the next morning, he said, ‘I believe this very deer crossed the river with me yesterday; for an Indian with a deer that he had killed came over in the boat that carried me.’”

“As president of Texas for two terms, most of Houston’s travel was official and necessary, such as inspecting army conditions, or to Indian councils to try and keep peace on the frontier,” says James L. Haley, a historian and author who wrote the 2002 biography Sam Houston. “Travel in Texas was rugged—poor roads, poor accommodations—but with his wife, Margaret, in Houston and the capital in either Austin or Washington on the Brazos, he had to make that trip frequently.”

Houston had a penchant for fine horses, but his private secretary convinced him to try a mule. “He was mortified at riding a mule,” Haley says, “but once he acquired ‘Bruin’ he could make the trip from Austin in three days instead of four, and he rode him habitually for years.”

Redlands rambler

Such travel must have required a buoyant spirit to overcome the weather, the beasts of burden, and the perpetual dependency on strangers—whoever was willing to help push a cart through the muck or host a boarder for the night. When he first crossed into Texas, however, Houston made his way to Nacogdoches, where he already had a friend in Adolphus Sterne, a German merchant and the town’s top civil official. At the time, the town of 1,300 was the hub of the restless Redlands, a frontier outpost simmering with opportunists and end-of-the-liners.

Sterne and his wife, Eva Catherine Sterne, built their dogtrot home in 1830 from pine wood, using bois d’arc stumps for piers. In the 1980s, Nacogdoches restored the home with its red-brick chimney, long porch, and wood-shingled roof. Houston’s fingerprints are all over the Sterne-Hoya House Museum and Library, including in a parlor that’s maintained as the Sternes would have kept it. The displays include an 1833 merchant account book showing Houston’s purchase of six grogs (a sugary rum cocktail) and reproductions of letters he wrote in the “criss-cross” style. Paper was in short supply, but with horizontal and vertical lines of script on each side, Houston could squeeze four pages of writing onto one sheet.

In about 1833, the Sternes’ parlor hosted Houston’s baptism into the Catholic Church. In The Raven, biographer Marquis James notes Houston was known as a “Muldoon Catholic,” one of many Americans inducted into the faith in Texas by an Irish priest named Miguel Muldoon. Why all the converts? Mexico required landowners to be Catholic.

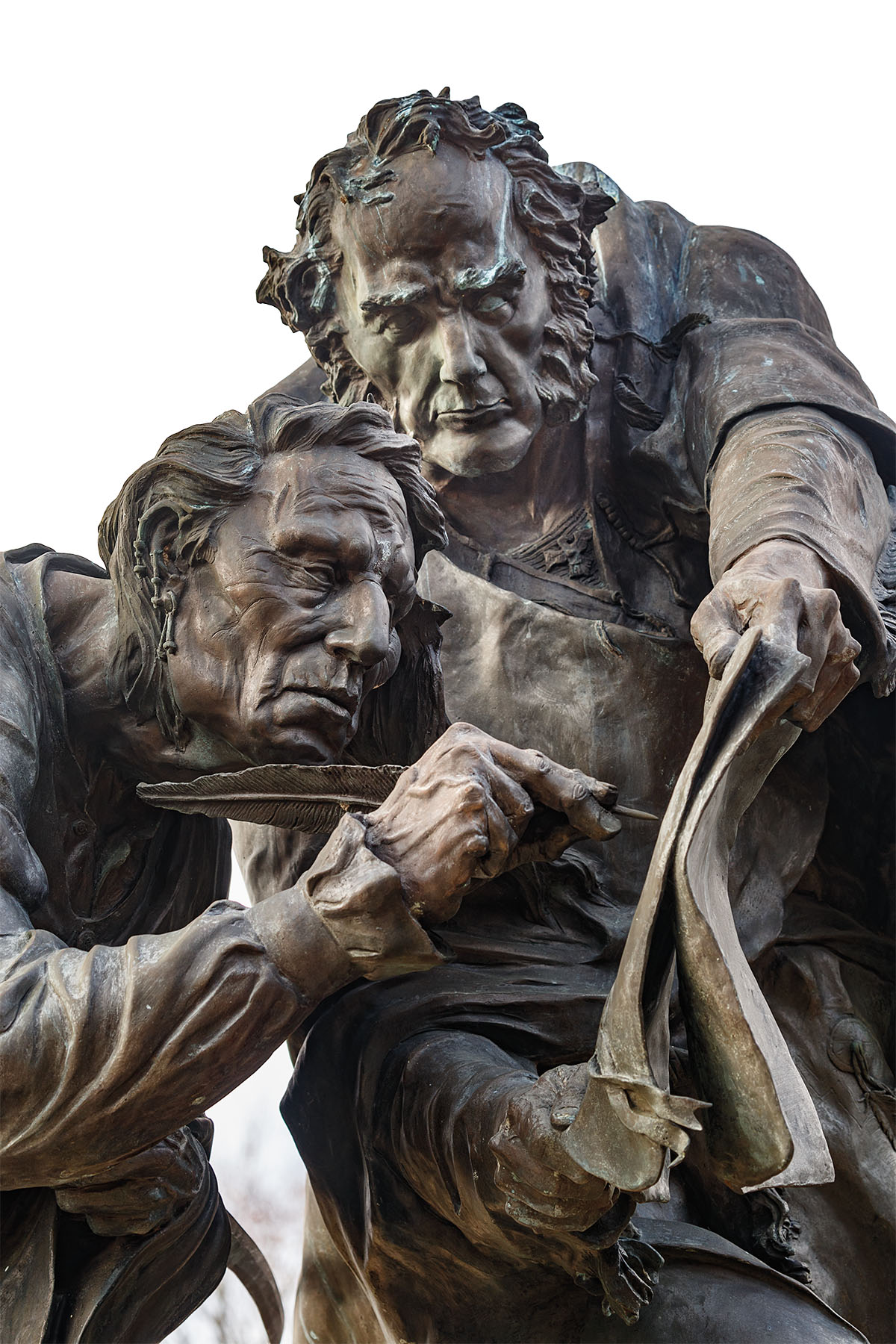

About two years later, as the Texas Revolution commenced, Houston returned to the Sternes’ home for a treaty conference with Chief Bowles, who lived in a nearby Cherokee settlement. In exchange for peace and neutrality during the revolution, Houston promised Texas would grant East Texas land to the Cherokee.

The museum keeps a marble table in the center of the parlor to tell the story of the meeting. “Chief Bowles walks into the parlor to sign this document, and he sees all these white men sitting around the room, and he sees the big marble centerpiece table,” explains Morgan Tingle, a tour guide. “He assumes it’s the seat of honor for him because he’s the guest at these talks. And so he climbed on top of the table and sat there.”

Once Texas became a republic, the government reneged on the treaty in spite of Houston’s objections, leading the Cherokee to fight Texas soldiers in 1839 at the Battle of the Neches, where Bowles was killed. Houston argued for policies of coexistence with the native population, but his political adversaries repeatedly acted otherwise. Still, the historical memory of “The Raven”—Houston’s Cherokee name—garners respect among native descendants.

In the early 1860s, Houston successfully lobbied to exempt men in the Alabama and Coushatta tribes from Confederate conscription. At the Livingston-area reservation of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, a monument to those warriors stands on a lawn within sight of the tribe’s headquarters and casino. The marker occupies the spot of an old “treaty oak” where Houston and tribal leaders would meet to discuss current affairs, says Bryant Celestine, the tribe’s historic preservation officer. “We refer to Houston as ‘grandfather’ to this day,” he adds.

Sam Houston’s East Texas

The Sterne-Hoya House Museum and Library,

211 S. Lanana St., Nacogdoches. 936-560-5426

The Sam Houston Memorial Museum,

1402 19th St., Huntsville. 936-294-1832

The General Sam Houston Folk Festival

May 15-17 on the grounds of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum.

The Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas,

571 State Park Road 56, Livingston. 936-563-1100

San Jacinto Museum of History at the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site,

1 Monument Circle, La Porte. 281-479-2421

The San Jacinto Day Festival

features a reenactment of the Battle of San Jacinto, April 18 at the San Jacinto Monument.

At home in Huntsville

Further south, in Huntsville, Native Americans once camped on a hill overlooking the Houston residence during Sam’s tenure as a U.S. senator (1846-59). A gazebo occupies the old campsite among the pines near 19th Street, above the Sam Houston Memorial Museum on the campus of Sam Houston State University.

“As he would come home, he would make his way through East Texas and visit with various people,” says Michael Sproat, the museum’s curator. “And there would be an encampment of Native Americans who had set up their tents and waited for him to keep track of news from the national scene.”

Houston’s spirit suffuses the 15-acre complex, which protects structures from when Sam and his third wife, Margaret Lea, lived here from 1848 to 1858. The Houstons had lived on a 2,000-acre plantation east of town, but with Sam frequently gone to D.C., Margaret opted to move to what was then a 200-acre property on Huntsville’s outskirts. Houston was famously deferential to Margaret, a refined Alabamian whom historians credit with coaxing Houston off the booze and into the Baptist church. Visitors can poke their heads into the Houstons’ two-story dogtrot home, where four of their eight children were born; Houston’s law office; and the Steamboat House, a Houston residence that was relocated from its original site elsewhere in town. Its parlor is set up just as it was for Sam’s funeral in 1863.

In the museum’s rotunda, exhibits chronicle Houston’s life and times with a collection that gives the impression you’ve stepped into the Houstons’ personal storage vault. In one display, the saddle Santa Anna rode at San Jacinto; in another, Margaret’s pocket hymnal; in another, Sam’s signature jaguar-skin vest, a gift he received from the Cherokee. Houston intentionally mislabeled it a leopard-skin vest because, he said, “A leopard never changes its spots.”

The Houstons’ old home comes alive each May during the General Sam Houston Folk Festival, when visitors can watch as blacksmiths pound out molten steel nails and seamstresses spin yarn from wool on a wooden wheel. The event charges the current of historical imagination that inhabits the museum and the whole of Huntsville. Touring the Sam Houston museum is a rite of passage for Huntsville-area students—roughly 10,000 visit annually on school field trips. In fact, both Sproat and his colleague Mac Woodward, the museum director, visited as children.

“It had a great influence on me,” says Woodward, who served as Huntsville mayor and on the City Council. “I didn’t know much history at that time, but I knew Sam Houston lived here. I knew he was a big deal and that he was a part of this community. So it made him a real person rather than a mythical figure or a hero.”

“I didn’t know much history at that time, but I knew Sam Houston lived here. I knew he was a big deal and that he was a part of this community. So it made him a real person rather than a mythical figure or a hero.”

Legendary Status

While the Sam Houston Memorial Museum personalizes Houston, Huntsville also gives him the hero treatment in the form of a 67-foot-tall statue. Artist David Adickes built the concrete façade likeness against a backdrop of pine and sweetgum trees along Interstate 45. Climbing isn’t allowed, but if you could somehow sit on Big Sam’s head, you and the general could see nearly all the way to San Jacinto, site of his defining moment.

San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site in La Porte preserves the marshy, brush-covered prairie where the Battle of San Jacinto unfolded. Back in 1936, 100 years after the conflict, Texas didn’t mess around when it came time to honor the state’s centennial. The most audacious example is the San Jacinto Monument, a 570-foot art deco shaft topped by a 220-ton star. The base holds the monument museum, where exhibits tell San Jacinto’s story with a film, paintings, and artifacts related to key players in the battle.

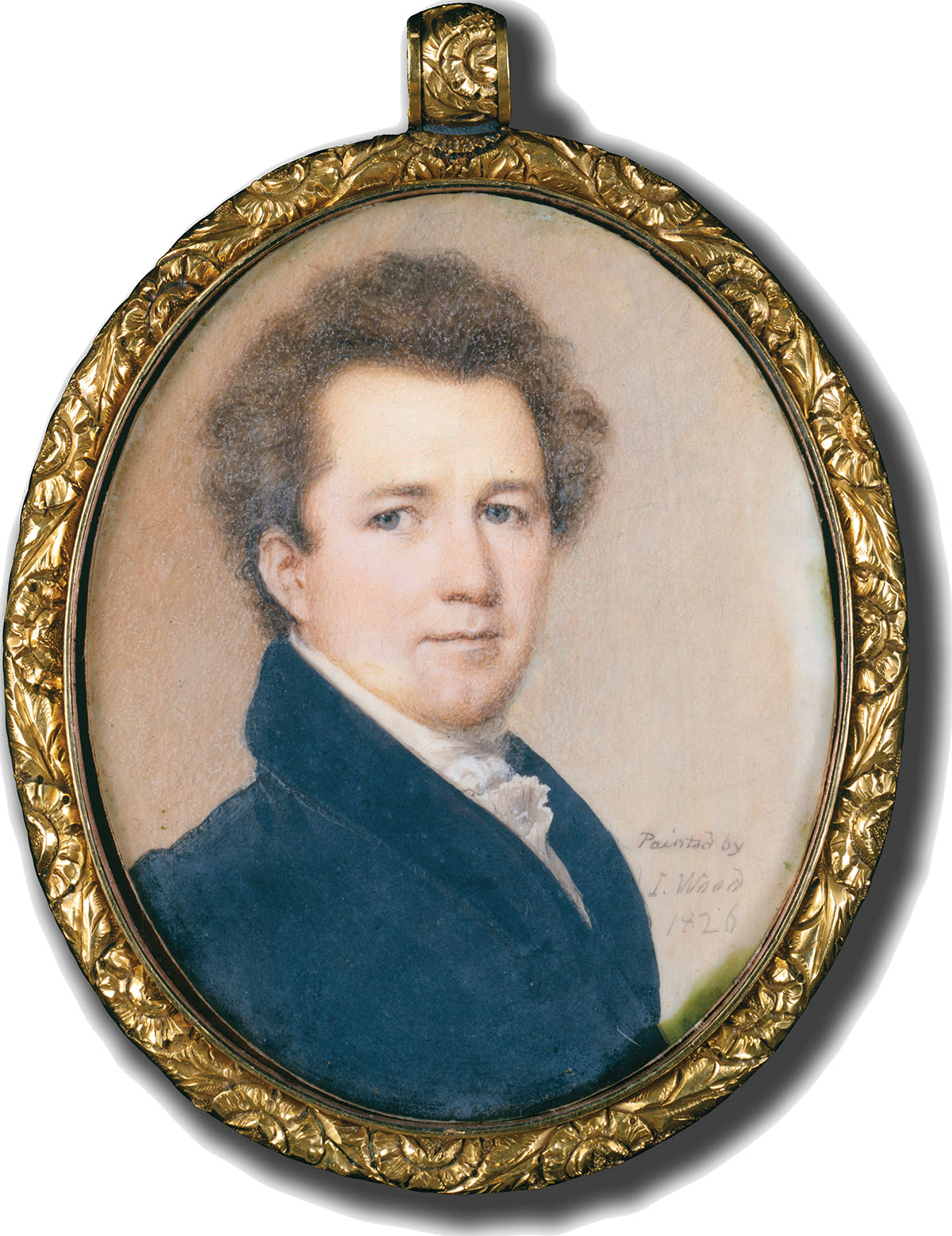

The collection includes the oldest-known image of Houston, a miniature painting from 1826, when he was a 33-year-old congressman from Tennessee who probably had never entertained a thought of moving to Texas. The museum also displays Houston’s “honor ring,” a gold band inscribed with the word. His mother gave it to him as a boy, and he wore it on his pinkie the rest of his life.

On the trail of Houston artifacts across East Texas, it doesn’t take long to chip through the mythic portrayal of Houston to reveal his humanity. He had his failings. He owned slaves, a conflicting reality of the era; he drank too much before giving it up; his temper got him into a street fight that made the national news; and he was part of Texas’ first-ever official divorce (the legal separation from Eliza Allen in Tennessee). But he’s also remembered for his resilience. He got knocked down repeatedly, but he was never afraid to start over. He took principled positions in the face of popular public sentiment, including his support of Native Americans and his Unionist stand in secessionist Texas. When he refused to pledge allegiance to the Confederacy, he was kicked out of the governorship, his final public office. As the ring now preserved at the San Jacinto museum suggests, Houston lived life with a resonating sense of integrity.

Back along Buffalo Bayou, filmmaker Florian marvels at the consequences of Houston’s decision to spare Santa Anna’s life. It was a watershed moment that precipitated Texas independence and its subsequent annexation into the United States. Without statehood, there likely wouldn’t have been the Mexican-American War or Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, with which the U.S. bought the territory encompassing much of Texas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

“Think about a map of the United States and the change of sovereignty of all that land,” Florian says. “Houston had a temper, but he had the ability to rein in his emotions and make the right decision not to kill Santa Anna. You never really know what the consequences of a decision are going to be—an ethical decision, a pragmatic decision. And in this case they were enormous.”