It’s no simple task, following the footsteps of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, the first nonnative to step foot in Texas and live to write a book about it. First off, if you want to do it right, you’d have to do it naked. And hungry. And how do you find traces of a thwarted Spanish conquistador, thirsty for gold and glory, who washed up on the coast near Galveston one cold November in 1528 and then walked hundreds of miles over many years, encountering dozens of native groups along the way?

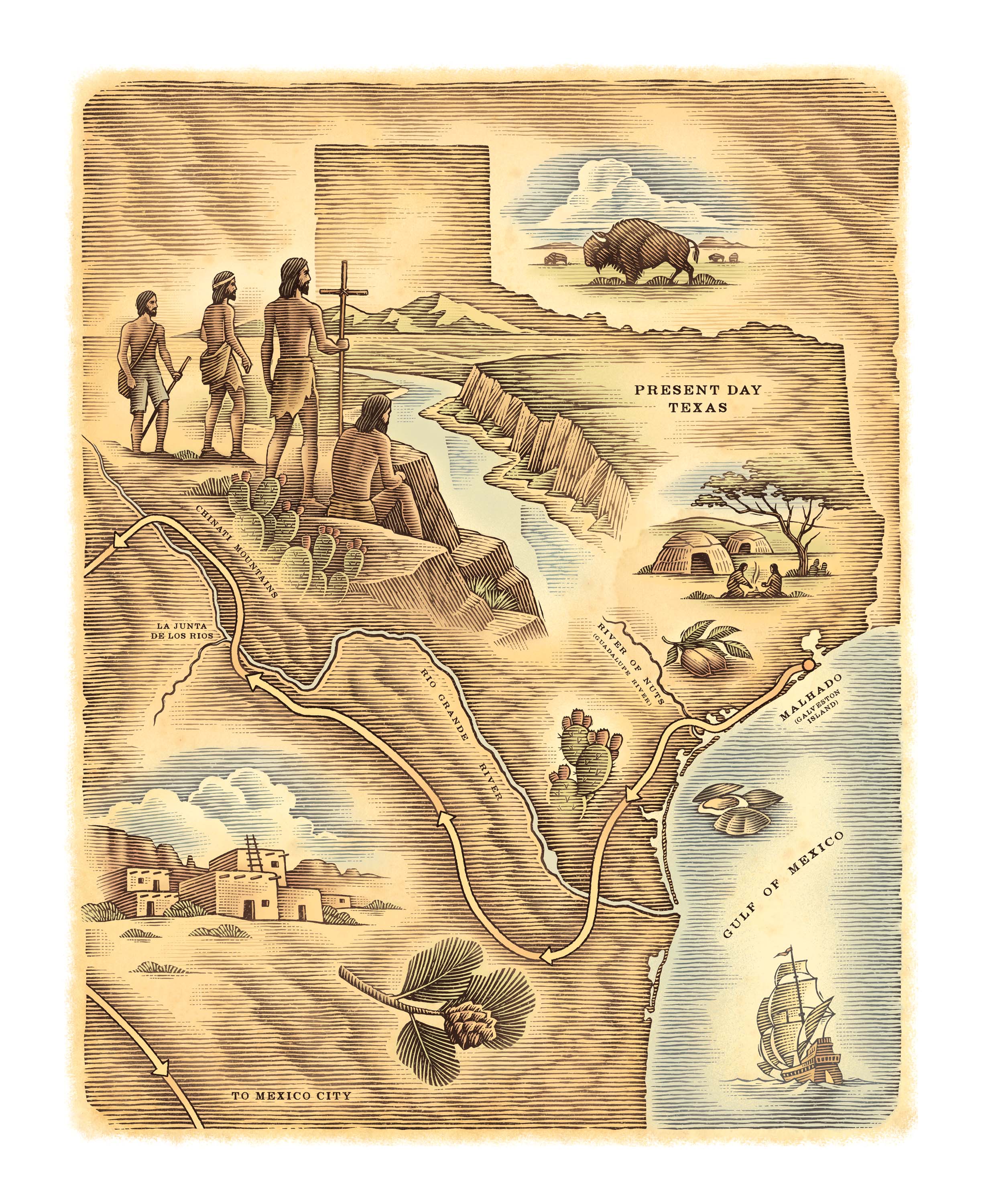

Further complicating matters, we don’t know exactly where he went. Although the book Cabeza de Vaca later wrote about his wild trek, La Relación, is full of juicy details, scholars rely on educated guesses to surmise his route. They have debated this, sometimes hotly, since the 1850s at least. Therefore my journey, which loosely follows the route proposed by the late Alex D. Krieger, an archeologist at the University of Texas from 1939 to 1956, is more impressionistic than precise.

I am seeking traces of this scrappy survivor—far more than just a funny name from Texas history class (Cabeza de Vaca translates to “Cow Head”)—because there is still much to learn from his odyssey. While interpretations of La Relación vary, there is no question he overcame astonishing odds to be the first chronicler of Texas. He was the first to record its plants and animals, the first to advocate for the people he met here, and the first to seek a peaceful coexistence rather than kill or enslave the natives like other Spanish conquistadors.

He was also the first Texas travel writer. He sat down with his quill and ink well to figure out—like me—how to relay his saga in a way that was respectful to those he met and meaningful for his readers. Because he was the first to write about our state, and often did so with an endearing openness, Cabeza de Vaca is my personal patron saint of Texas travel writers.

Malhado, The isle of Misfortune

“To this island we gave the name Malhado,” Cabeza de Vaca wrote in La Relación, his report for the Spanish king, published first in 1542 with a second edition in 1555. Translated as “The Isle of Misfortune,” Malhado is a fitting name given that, of the 80 men in the expedition who washed up near Galveston on makeshift barges—having abandoned their ships back in Florida—only a few survivors made it off the island.

But there were some silver linings. The natives who found the men on the beach handed Cabeza de Vaca arrows, a sign of friendship. Then they carried the foreigners back to their huts, lighting bonfires on the way to keep them from freezing. Cabeza de Vaca learned their languages and observed their customs. And even though at first he was a slave, he was savvy enough to earn their respect and eventually gain some freedom as a traveling merchant.

As I drive along the Galveston Seawall, with high-rises and the carnival rides of the Pleasure Pier framing my view, I’m hard-pressed to imagine such exploits once unfolded nearby. But that changes inside The Bryan Museum, where I gaze upon one of the handful of surviving copies of the 1555 edition of La Relación, a small leather soft-bound book. It’s so unassuming, visitors around me walk right past it.

But knowing what I know, the sight of this 464-year-old treasure gives me a kind of historical vertigo, like falling back through the centuries. While the book is protected behind glass, I can scroll through its pages via a computer screen. I see the words in which Cabeza de Vaca presented his story to the king: “I had no opportunity to perform greater service than this, which is to bring to Your Majesty an account of all that I was able to observe and learn in the nine years that I walked lost and naked through many and very strange lands … because this alone is what a man who came away naked could carry out with him.”

He wrote a lot about nakedness—19 times according to the index of a 1999 translation of the book by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz. It must have been shocking, after all, for a devout Catholic from the Spanish aristocracy to lose his armor and walk through Texas buck naked. But that’s what the locals did, so he did it, too. It’s also a metaphor. The guy lost everything.

I drive down the coast and camp by myself at Galveston Island State Park. This is the closest I can get to the wilderness of Malhado and the loneliness Cabeza de Vaca must have felt as the sole European slave to the tribe that took him in, his countrymen dying off, the whereabouts of other survivors unknown. For about four years, he lived with the hunter-gatherers along this stretch of coast.

Sitting on the driftwood-strewn beach, I watch the sky darken as a storm begins to brew over the ocean. It’s going to be a wet and blustery night. I wonder if Cabeza de Vaca looked back across this water and lamented all he’d left behind in Spain.

I try to set up my tent on the bay side of the park just as the squall hits, the winds whipping the tent out of my hands and forcing me to chase it down. Later, as I try to sleep, rain drips through my tent and a mosquito buzzes around my head. On this we can commiserate. “We found throughout the land a very great quantity of mosquitoes of three types that are very bad and vexatious, and all the rest of the summer they exhausted us,” Cabeza de Vaca recalled.

Reunion at the River of Nuts

After his years with the tribes around Malhado, Cabeza de Vaca headed south, seeking the Spanish settlement at Rio Pánuco, in what is now the Mexican state of Veracruz. At Matagorda Bay, he met the Quevenes group, who reported seeing other foreigners traveling with tribes headed for the harvest at the River of Nuts, which scholars agree is the lower Guadalupe River near Victoria. Here, in 1533, the Spaniard reunited with Estevanico (a slave from Morocco), Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and Alonso Castillo Maldonado—the three remaining survivors of the expedition. “This day was one of the days of greatest pleasure that we have had in our lives,” he wrote.

Today, Riverside Park in Victoria bursts with pecan trees. Sitting on a picnic table and chomping on trail mix, I can imagine Cabeza de Vaca’s joy at reuniting with his castaway pals, the four of them gorging on sweet pecans. As a cadre, united, they would help each other on the long road ahead. Had they not found each other, Cabeza de Vaca would likely not have survived—all he discovered about early Texas history and later wrote about would be lost.

I leave Victoria and drive southeast toward Seadrift, where the Guadalupe flows into San Antonio Bay. On the road, I consider the people Cabeza de Vaca described who once called this land home: The People of the Figs, the Camoles, and the Guaycones. “All these peoples have dwellings and villages and diverse languages,” he wrote. His depictions often convey awe: He describes the groups along the Texas coast, for example, as people who “see and hear more and they have sharper senses than any other men that I think there are in the world.” His words are all we have left of them.

The Land of the Tunas

Most scholars believe the foursome, still captive, headed down through South Texas, possibly near Alice, for the annual prickly pear harvest. As I cruise down US 77 listening to the audiobook of La Relación, the landscape strikes me as way too spiny to offer anything edible. However, Cabeza de Vaca encountered something different among the fields of cactus. “The best season that these people have,” he wrote, “is when they eat the prickly pears, because then they are not hungry, and they spend all their time dancing and eating of them, night and day.”

In early fall of 1534, the four travelers escaped from captivity and crossed the Rio Grande south of Laredo near Falcon Lake. They then turned away from the coast and headed west toward the mountains of northeastern Mexico. Along the way, they attracted hundreds of followers who considered them healers who “came from the sky.” In an extraordinary metamorphosis from slaves to heroes, the Europeans—now with an entourage—blessed the natives’ babies and food, and received a bounty of gifts in return. After their transformative trek across Mexico, they eventually crossed the Rio Grande near Presidio and arrived back in Texas.

Before driving out to Presidio, I detour to The Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos, home to another 1555 edition of La Relación. The Wittliff released a revamped digital version of its copy on its website in 2018. It quickly became the archive’s most popular search item, with more than 100,000 hits per year.

On the top floor of Texas State’s Alkek Library, Wittliff literary curator Steve Davis sets down an archival box just under a foot long and lifts the leather-bound book from within. This time I get to actually touch its almost 500-year-old rag-paper pages, a spellbinding sensation.

Davis tells me Cabeza de Vaca is making a comeback in Texas history books. “J. Frank Dobie, who basically invented Texas literature, was advocating in the 1920s that students should be learning the story of Cabeza de Vaca,” he says. “Somehow it didn’t happen. Thanks to changes over the last 20 or 30 years, students have been able to get that story more in their Texas history classes. It’s finally in the forefront where it deserves to be.”

Just a short walk from the archive, Don Olson, a Texas State physicist, historical astronomer, and scholar of Cabeza de Vaca, works in an office lined with books and folders stuffed with his research on the Spaniard. High on one shelf rests a cooler Olson filled with branches and nuts from the piñon pine trees Cabeza de Vaca praised in his memories of northern Mexico: “There are throughout that land small pines, and … they have a very thin hull.”

In 1996, Olson led a team of students to Mexico to find those pines, evidence for the theory that Cabeza de Vaca dipped south of the Rio Grande; pines in West Texas and New Mexico have thick hulls. “The truth is very hard to find,” Olson says. He opens the cooler for me, and even though they’ve been in there for years, the piñon needles still smell like the pine-filled Mexican mountains Cabeza de Vaca crossed in 1535.

I ask the professor why the Wittliff’s online version of La Relación has so many hits. “I don’t know,” replies Olson, who’s currently working on an article that examines astronomical references in Cabeza de Vaca’s book. “I can only tell you why I am doing this. The Relación is an important book, the first written about this land we now call Texas. I am a physicist, and I want to know the facts—where he went and when. I’m trying to solve the mysteries.”

La Junta and the People of the Cows

Amid the debate about where Cabeza de Vaca traveled, historians agree he visited La Junta de los Rios, a settlement where the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos meet near Presidio. He called these natives, who were bison-hunters, “The People of the Cows,” and he was elated to find they were farmers, the first he’d encountered in Texas.

“They gave us frijoles and squash to eat,” he wrote. “The manner in which they cook them is so novel that, for being such, I wanted to put it here so that the extraordinary ingenuity and industry of humankind might be seen and known in all its diversity.”

I drive to Presidio the same weekend a former ambassador from Spain, Miguel Ángel Fernández de Mazarambroz, is in town to meet with archeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and Sul Ross State University’s Center for Big Bend Studies. It’s part of a reunion organized by Bill Millet, director of the 2018 documentary Texas Before the Alamo. This crew believes that by sharing archeological resources across borders, we can strengthen our countries’ relationships.

“The European history of Texas starts 500 years ago, not with the Alamo,” de Mazarambroz says. “Cabeza de Vaca is like a Texan in the sense that he is a strong man, and you see he was also a kind man. We shouldn’t cut off that part of history.”

From La Junta, Cabeza de Vaca and his companions walked northwest along the Rio Grande and then crossed back into Mexico where they eventually came upon Spaniards on horseback. Shocked to find these ragtag naked survivors, the Spaniards led Cabeza de Vaca to Mexico City. From there he headed to a port for a long journey back to Spain. The castaway was eager to share his new knowledge with the king and, many historians believe, advocate for a more humane colonization of the West Indies. While details are uncertain, it is believed he lived out his final days in Spain in his hometown of Jerez de La Frontera and died in either Valladolid or Seville.

On a cool spring morning, I walk along the Rio Grande, just outside of Presidio, until I see the actual “la junta,” or joining, of the Conchos and Rio Grande. Cabeza de Vaca wrote that the Rio Grande “had water that came up to our chests; it was probably as wide as that of Seville.” Today, the river here is so narrow I could jump across it.

My heart skips to see the jagged Chinati Mountains standing tall on the horizon. Cabeza de Vaca walked toward these mountains, too, stepping one bare foot after another. After so many years lost, he was transformed. No longer a conqueror, he’d enlarged his worldview and become an ally to the locals, the best things a traveler can do. What he did bring back with him—his story—is the most valuable gold there is.

Cabeza de Vaca Travel Tips:

1

Keep an Open Mind:

Rather than criticize when he realized that an indigenous group did not have a Western concept of time, he wrote that they were “very skilled and well-practiced” in understanding “the differences between the times when the fruit comes to mature … and the stars appear.”

2

Help Out in a Jam:

Cabeza de Vaca carried his companions who couldn’t swim across rivers. He removed an arrow point from the torso of a native man. When you’re on the road, it feels good to be useful.

3

Listen and ask Questions:

Cabeza de Vaca asked why indigenous mothers breastfed their children until they were 12, and they explained that it was the best way to help their children survive food scarcity. Rather than judge, he listened and learned.

4

Learn the Language:

Cabeza de Vaca learned at least six different languages. When the locals realized he could speak with them, his chances of survival shot up.

5

Express Gratitude:

Cabeza de Vaca was grateful to the locals who helped him, and they showed their appreciation for him in return. One group gave him 600 deer hearts—a prized food source—as a thank-you gift, most likely for a healing he had performed.