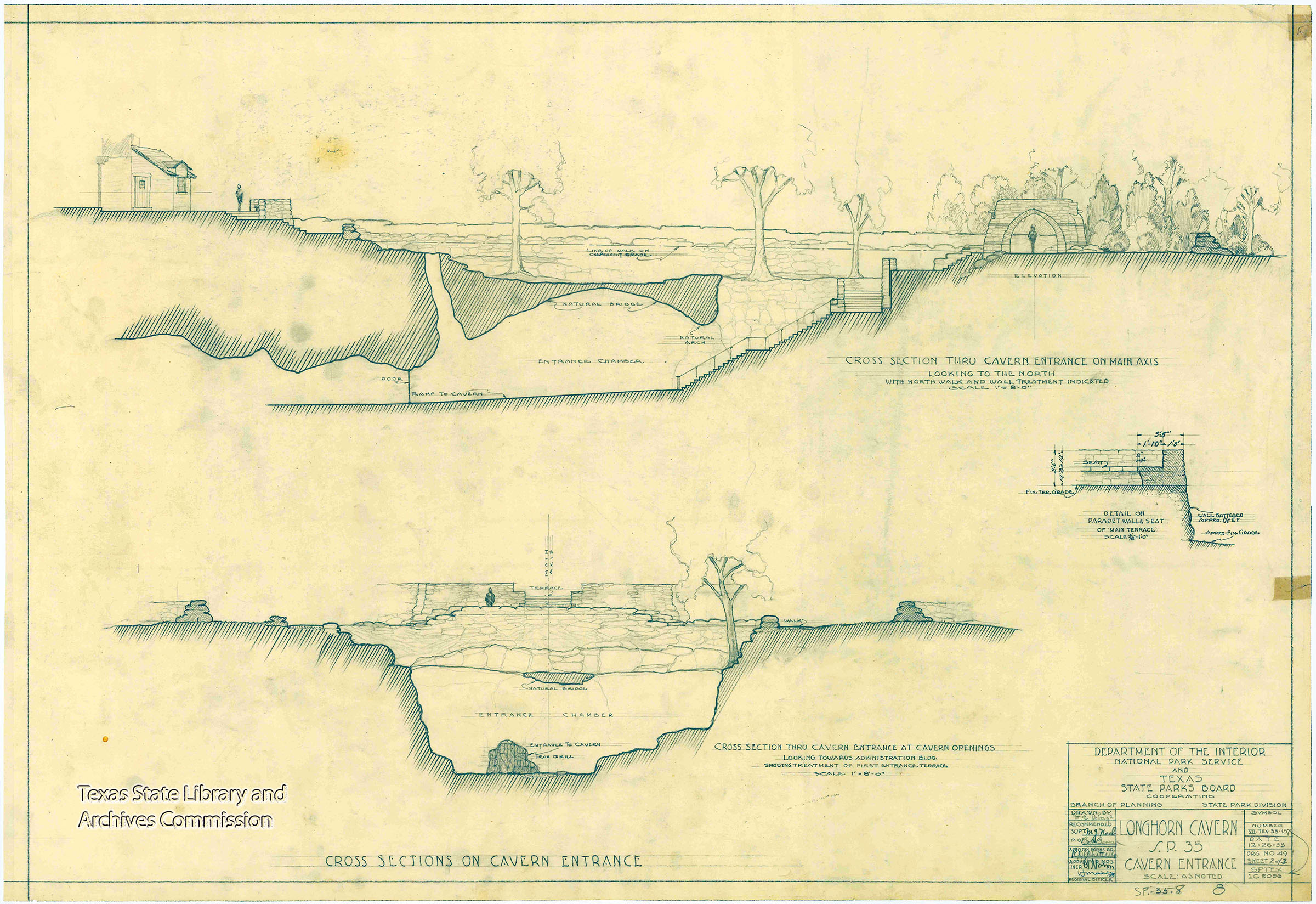

As soon as I descend the stairway leading into Longhorn Cavern, the temperature drops. A great rush of air envelops me while water drops fall from the natural rock bridge overhead. Looking up, I see hanging vines descending from one of the sinkholes, and just beyond them, a clear sky.

The entrances at Longhorn Cavern State Park, an hour and a half northwest of Austin, originated as sinkholes, or dolines. The holes began forming 500 million years ago when rainwater seeped inside of pores and fractures in the area’s limestone and pooled in depressions, causing the roof to collapse.”

Surface water began to enter the sinkhole and push its way through the hillside,” says park manager Evan Archilla, who is leading me on a tour of the cavern. The water then formed an underground river, which carved out chambers and rooms; wore down walls; and whirlpooled high, creating domes in the ceiling.

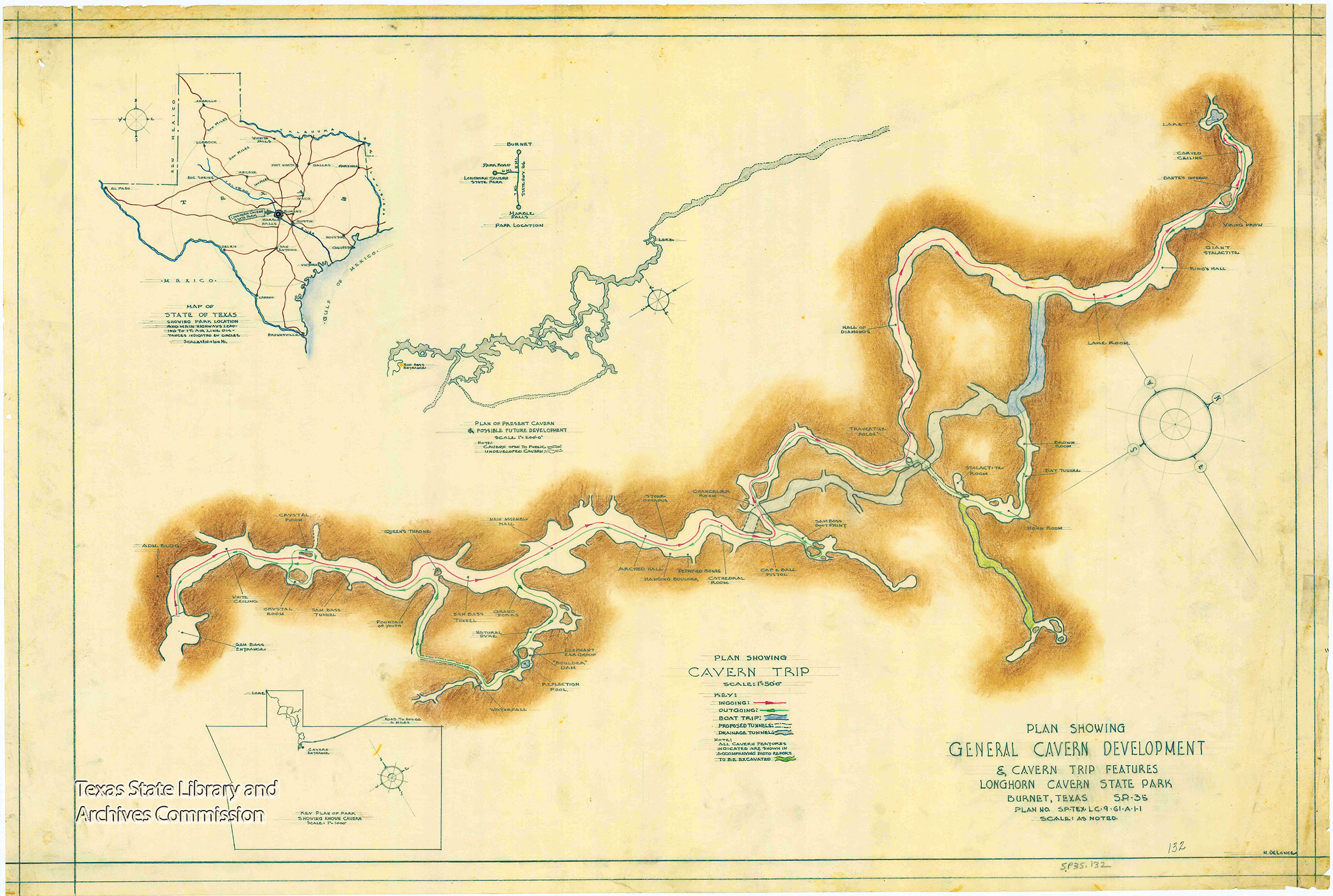

Archilla and I tour cave after cave in the 135-foot-deep cavern, walking through tunnels of crystal and great amphitheaters of white, swirling stone—geologic columns, draperies, and ancient water-carved channels. But before it was possible to access these deeper reaches, all the rock, silt, dirt, and mud that had washed in had to be excavated.

A group of 200 Civilian Conservation Corps workers, many of them only teenagers, arrived for that job in May 1934. Though prison laborers from Huntsville had started the excavation project, CCC Company 854 greatly expanded the accessibility of the cavern for tourists. The underground network, which opened as a state park in 1938, is the largest cavern in the state park system.

Plans for installing park infrastructure weren’t set in stone when the Texas State Parks Board was founded in 1923, according to Toni Mason, a preservation services historian for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “The formal paperwork you don’t see until the ’30s, until there was the federal program in place that brought the workforce to create the amenities,” she says. “So, I don’t think we’d have the park system today if we hadn’t had that help from the federal government and the CCC.

”The work was a windfall for CCC enrollees. “Back then, a dollar a day was a lot of money,” said former Company 854 member Hanno Pape in an interview for the 2002 oral history project CCC Boys of Texas, Tell Us Your Story. “For a dollar a day, we could survive real well. ”Originally from New Braunfels, Pape had been assigned to work on building and excavating Longhorn Cavern State Park near Burnet.

Like most Americans after the stock market crash, CCC enrollees were struggling financially, and they signed up to help their families back home. During the Great Depression, unemployment peaked at 25%. In Texas, many families abandoned farms ruined by the Dust Bowl and traveled west. Haboobs filled the sky like looming thunderstorms and made for apocalyptic scenes across the Great Plains.

Deep in the Heart

Longhorn Cavern is only one of several Texas state parks with built-in caves. Here’s information on how to visit.

Longhorn Cavern State Park offers 90-minute historical walking tours, Wild Cave tours that require crawling in tight spaces, and a CCC museum in the administration building.

Guided tours of Kickapoo Cavern State Park, 150 miles west of San Antonio, take place every Saturday at 1 p.m. Make a reservation to ensure your spot in the 10-person tour.

Devil’s Sinkhole State Natural Area is known for its bat population, which roosts in its caverns from late spring through early fall. The natural area two hours northwest of San Antonio is only open by guided tour.

Colorado Bend State Park, 100 miles northwest of Austin, offers Wild Cave tours of some of its 400 caves.

Newly elected president Franklin D. Roosevelt established a series of New Deal programs to get people back to work. The CCC began in March 1933 to get unemployed young men off the streets, and it worked: Tens of thousands of impoverished boys signed up in Texas alone. Boys like Pape would go on to help build the infrastructure of Texas’ state parks from 1933 to 1942.

“Those young men, through hard work and manual labor, cleared that cavern so it was accessible to people to utilize and see today,” says Barrett Durst, superintendent of sister park Inks Lake.

Longhorn Cavern opened to private parties about two years before Company 854 arrived, and it had a storied history before that. About 400 years ago, Comanches held council meetings in the cavern. In the 1860s the Confederate army used them to store gunpowder. Once called “Sherrard’s Cave” after its location in rancher D.G. Sherrard’s pasture, the cavern was a place visitors explored by lantern or candlelight in the early 1900s, guided by a rope to help them find their way back out. Names carved in 1919 can still be seen on a formation of flowstone and calcite crystals near the Queen’s Throne Room. In the early ’30s, the attraction doubled as a dance hall, where bands like the Harris Brother’s Texans performed live on brass instruments. An opening in the rock exposed the starry sky.

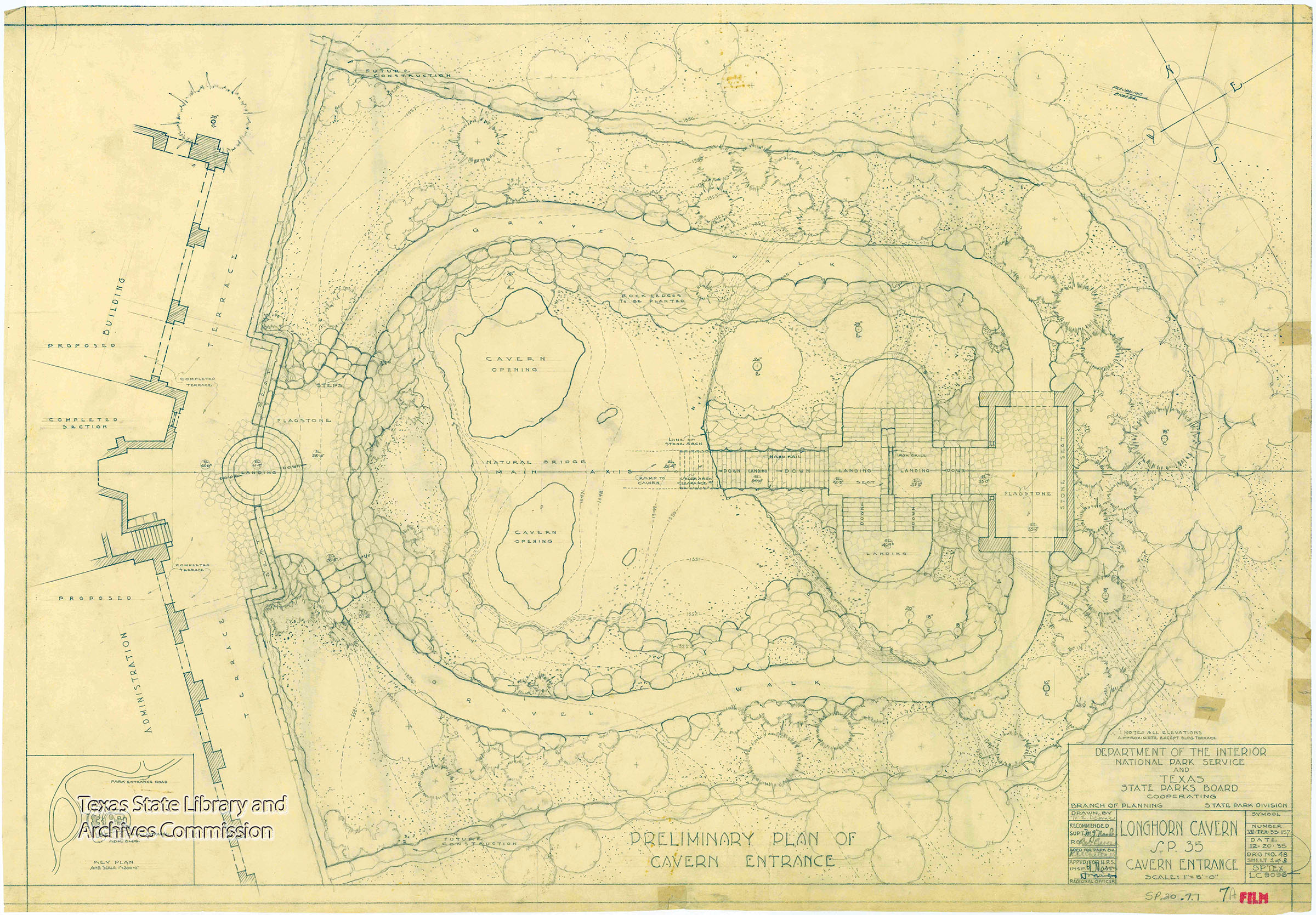

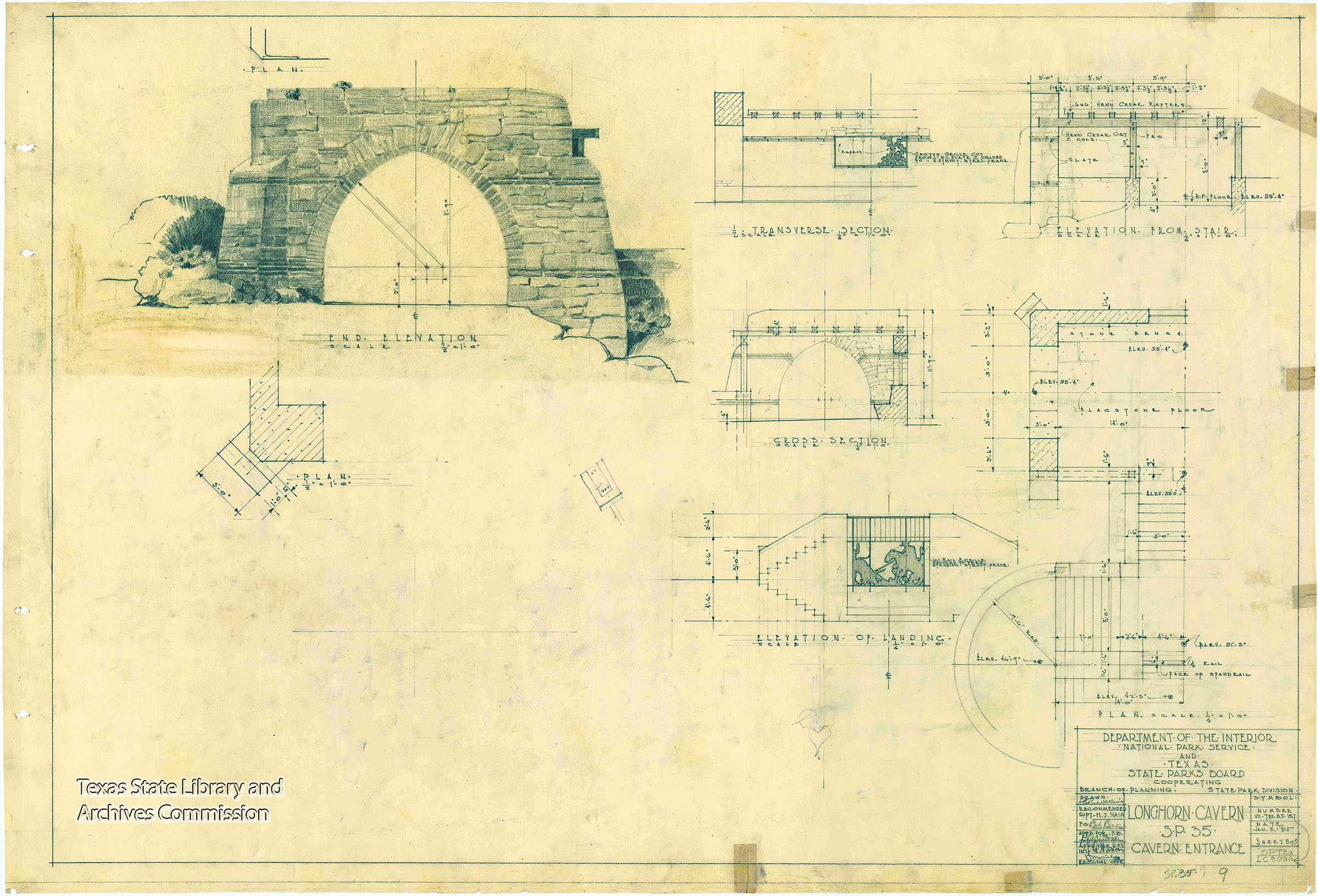

Even when excavating, Company 854 didn’t use any heavy equipment, according to Pape: “just wheelbarrows and muscle power.” When they had finished, 2.5 tons of dirt and debris had been removed. After they cleared caves, the workers built trails and installed more than 2 miles of indirect lighting. They built Park Road 4, a 6-mile road that connected US 281 to the cavern. They also built an administration building, an observation tower overlooking HooverValley, and a stairway leading down to the main entrance of the cavern, all by hand.

“The native materials, the thickness of everything, there’s a weight to these structures because they’re built with the earth,” Archilla says as we explore the cave. “They’re built with this rock, these trees, hand-hewn lumber. It’s almost like they grew out of the ground in the places where these guys did work.”

Visitors can walk on the same stones the CCC laid 90 years ago. The cavern holds myriad stories, but its most compelling tale is that of the young men who performed the grueling, lasting work that made the park a reality. More than 50,000 boys made their way through the CCC in Texas, and 1,600 of them worked at Longhorn Cavern at some time in their tenure: kids like H.C. Hicks, who arrived a few years after Pape. “This park is a good example of the good work that was done by—and I’m going to say again—kids,” Hicks said in the oral history. “They were kids.”

Practical Jokers

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department set out to document the lives of former CCC workers with the 2002 oral history project CCCBoys of Texas, Tell Us Your Story. One interviewee from Company 854, Hanno Pape, was about 90 years old at the time of his interview. Pape was 18 when he dropped out of high school in New Braunfels to join the CCC in the 1930s.

He spoke about the difficult work the company completed, but he also reminisced about the fun and camaraderie with his fellow enrollees. He and his best friend, Bruno, would spend their off time swimming the river and “grappling for fish” below the dam. Bruno, Pape said, taught him how to catch them by hand. Pape and the other corpsmen slept in tents, four to each one, while stationed in Blanco. They pranked each other by “short-sheeting” and planting cockleburs in bedsheets for unsuspecting enrollees tucking themselves into bed. “We had a ball,” Pape said.

For more information on the CCC’s legacy in Texas parks, visit tpwd.texas.gov/ccc.