The view from High Lonesome Lane is remarkably empty. The narrow dirt road cuts through the southern High Plains, traversing the Rita Blanca National Grasslands in the northwest corner of the Texas Panhandle. An occasional hackberry tree or windmill breaks the prairie’s distant horizon. Grazing pronghorn, startled by the rarity of a passing car, dart along broken stretches of sagging barbed-wire fence. It’s conceivable to imagine what this territory would have been like in decades past, including when drought-ravaged settlers left their homes to escape the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

See related: Dust Bowl Resources ~ Droughts ~ Share your memories

In a region accustomed to weather extremes and spring “dusters,” the Dust Bowl—eight years of severe drought that blistered the Great Plains with blinding dust storms and agricultural losses—stands out for its exceptional hardship and lasting legacy. Places like the Rita Blanca Grasslands, which the federal government created in the 1930s to help restore the wind-eroded plains, recall a time period that was marked by environmental upheaval and the Great Depression. For travelers today, the story unfolds in the communities that survived the calamity and stuck around to share their memories.

Museums across the Panhandle Plains illuminate various aspects of the Dust Bowl era, from the tractors that plowed up the native grasslands to the early days of a fledgling folk singer named Woody Guthrie. In recent years, several institutions have revisited the Dust Bowl in recognition of important anniversaries (April marks 79 years since the infamous “Black Sunday” dust storm of 1935), the passing of the last survivors of the Dust Bowl, and a lingering drought that reminds us of rainfall’s unpredictability.

“You can find evidence of the Dust Bowl in the museums, in the historical archives, and in the personal memories of the folks who went through it,” says Paul Carlson, a historian of the American West and retired Texas Tech University professor. “People were forced out of their farms, off the land and into towns, and then you had the larger exodus of folks from the Panhandle Plains. You had years when people planted their crops two or three times and still had a failure. When that happened a couple of years in a row, you were in tough straits.”

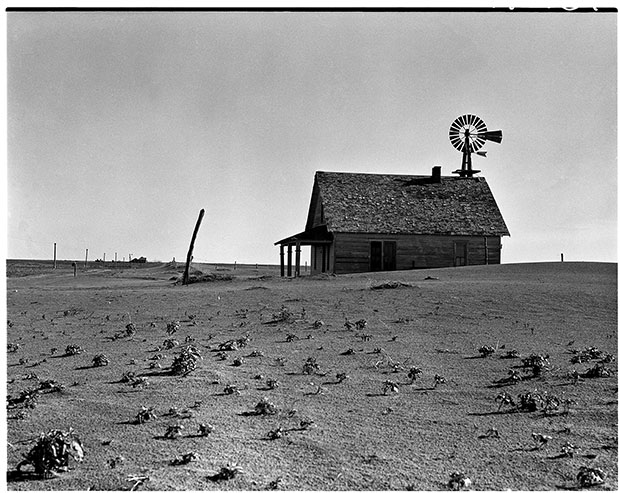

Arthur Rothstein/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-DIG-fsa-8b27557;

For grounding in regional history leading up to the Dust Bowl, the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon is worth a visit. In the Pioneer Town exhibit, visitors explore structures characteristic of the Panhandle at the dawn of the 20th Century, such as a mercantile shop and a Goodnight Ranch cowboy camp. Settlers poured into the Panhandle Plains in the early 1900s, beckoned by land developers who subdivided vast ranches into farmland. For a time, the weather cooperated with plentiful rainfall.

“The railroad was promoting the region and bringing people in, and they were buying up farmland,” explains Becky Livingston, the museum’s curator of history. “Farm crops were doing really well. But of course, the wet years didn’t last.”

The museum’s Farming the Plains exhibit elaborates on the boom-and-bust nature of farming in the southern High Plains. The exhibit explains how the advent of tractors, wheat demand driven by World War I, and a massive expansion of dry-land farming contributed to extensive plowing of native grasslands. While even uncultivated lands eroded during the 1930s drought, the plowing of the teens and ’20s worsened the soil erosion that characterized the Dust Bowl.

Museums across the Panhandle Plains illuminate various aspects of the Dust Bowl era, from the tractors that plowed up the native grasslands to the early days of a fledgling folk singer named Woody Guthrie.

In the Wild and Wacky Weather on the Panhandle Plains exhibit—open through February 1—visitors get a small taste of a Dust Bowl dirt storm, minus the grit. Set in a wooden farmhouse, the exhibit features historical video of people and livestock making their way through persistent blowing dirt, their heads bowed against the storm. A soundtrack of whipping winds accompanies the scene.

Gayle Bowen, an 86-year-old museum volunteer, grew up in the town of Post, where his father ran a wrecking yard and a tourist camp during the Dust Bowl years. He recalls watching the Black Sunday storm drop down from the Caprock escarpment and roll toward his family’s home on April 14, 1935.

“We couldn’t believe it, just rolling in like a freight train,” Gayle says. “Of course we had seen many a dust storm, but this was fearful, really. We went in the house together and that thing hit. We had one 40-watt bulb in the middle of the ceiling, and we had it on, but everything just went black. Sitting across the table, I couldn’t see you.”

That spectacular quality of the Dust Bowl continues to fire our memories and imaginations, reckons Andy Wilkinson, artist in residence at the Texas Tech University Southwest Collection in Lubbock. With fellow Lubbock musician Andy Hedges, Wilkinson released an album in 2012 called Mining the Motherlode, featuring songs and poems about the Dust Bowl, drought, and the depletion of the Ogallala Aquifer, today the main source of drinking and irrigation water for much of the southern High Plains.

Since the Dust Bowl, the Panhandle has experienced severe droughts in the 1950s and 2000s (2011 was Amarillo’s driest year on record with only seven inches of rain—13 inches below average). But the effects of those droughts have been tempered by improved agricultural practices, government soil-conservation programs, and the expansion of irrigated farming made possible by the tapping of the Ogallala.

‘The history of this place is that it’s really cyclical in terms of rainfall. But weather is one of those things—the moment it’s over, people forget it.’

“People look at the Dust Bowl as an aberration, because we’ve had worse droughts since and we haven’t had the Dust Bowl reoccur,” Wilkinson says. “The history of this place is that it’s really cyclical in terms of rainfall. But weather is one of those things—the moment it’s over, people forget it.”

In Lubbock, a visit to the National Ranching Heritage Center illuminates the living conditions of Panhandle-Plains residents during the Dust Bowl. The center’s 16-acre park features about 30 historic buildings that represent regional ranching history, including a 1903 “Box and Strip House.” Many families in the tree-scarce Panhandle Plains lived in such homes, which were nailed together with thin boards delivered by rail. The homes didn’t have insulation, and cracks between the boards made the homes notoriously porous to the elements.

“The only warm place in the winter was around the potbelly stove,” says Emily Wilkinson (Andy’s daughter), education manager at the center. “In the winter, they’d have lines of snow on the bed where the snow blew in, and when it was dusty, they’d have lines of dust.”

Also at the National Ranching Heritage Center, the historic Ropes Depot, stock pens, and cattle cars illustrate the railroad’s role in the ranching industry of the early 20th Century. The Santa Fe Railway originally opened the depot in 1918 to serve ranchers in the Ropesville area. During the Dust Bowl, some ranchers on the Panhandle Plains were forced to ship their cattle to market at reduced prices, or watch them perish from hunger on their parched, sand-covered pastures. Beef prices dropped with the market glut of cattle.

A lesser-known aspect of the Dust Bowl era is on display in Ropesville, the train depot’s original home about 25 miles southwest of Lubbock. Located on the edge of a cotton field, the historic Ropesville Project community hall recalls Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program. The federal government es-

tablished the Ropesville Project in 1936 to provide farming families with land and housing for a fresh start. The families paid rent based on their annual yield.

The Ropesville Project grew to 77 farms on about 16,000 acres before Congress disbanded the program in 1943, at which time participating families had the opportunity to buy their farms from the government. In 1959, former residents moved the old community hall from the countryside into the town of Ropesville. Inside the hall, you’ll find an exhibit with photographs of the project and its residents, original community blueprints, historic newspaper clippings (including an account of Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit), and recorded interviews of former residents.

The Ropesville Project grew to 77 farms on about 16,000 acres before Congress disbanded the program in 1943, at which time participating families had the opportunity to buy their farms from the government. In 1959, former residents moved the old community hall from the countryside into the town of Ropesville. Inside the hall, you’ll find an exhibit with photographs of the project and its residents, original community blueprints, historic newspaper clippings (including an account of Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit), and recorded interviews of former residents.

Charles Shannon and his family moved to a new farm in the Ropesville Project in 1938, when he was eight years old. His father’s crops included cotton, milo, and gooseneck maize.

“My parents saw [the resettlement project] as an advantage, because they knew they would get a chance to buy the farm,” says Shannon, now 83. “It was an opportunity that helped a lot of people. It had running water—and I’d been carrying water.”

While the federal government sought solutions to the environmental and economic challenges of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, the energy industry provided an economic buffer for some areas. In 1926, oil gave birth to the boomtown of Borger, whose history is recalled at the Hutchinson County Historical Museum. An exhibit called The Boom, The Bust & Ten Years of Dust chronicles the town’s oil-boom frenzy, dust storms, and rough-and-tumble development. The museum displays the exhibit periodically, including this January.

As an offshoot of Borger’s oil industry, companies burned the natural gas byproduct to create carbon black, an ingredient used in synthetic rubber tires. The production methods of the 1930s released copious amounts of carbon black into the air, which compounded the intensity of dust storms, says Lynn Hopkins, museum administrator.

“They would put newborn babies in a bassinet, and they would have to keep wet sheets over them,” she says. “Otherwise, the stuff was so strong that it would suffocate the babies.”

Indeed, “dust pneumonia”—characterized by an excess of dust in the lungs—was deadly for many young children of the Dust Bowl. The illness was so widespread that it prompted Woody Guthrie to write “Dust Pneumonia Blues,” a song about a doctor warning his suffering patient that he doesn’t have long to live.

‘This was where he (Woodie Guthrie) kind of formed himself. He read every book in the Pampa library. This is where he got the basis, I think, for what started his career as a songwriter and a man for the people.’

Woody knew well the difficulty of life during the Dust Bowl because he experienced it as a resident of Pampa, where he moved in 1929 at age 17 and lived until 1936. The troubadour’s time in the Panhandle is honored at Pampa’s Woody Guthrie Folk Music Center, which occupies the same red-brick storefront that once housed Harris Drug Store, where Woody worked as a soda jerk.

The center’s walls are covered with Woody memorabilia and information about Pampa history. Visitors can also pick up a walking tour brochure and audio guide that focuses on Pampa of the 1930s, including the still-open Coney Island Café, known for its chili and homemade pies. On Friday nights, the center hosts musicians for a jam session that always includes at least a couple of Woody songs.

“Mainly we just try to keep the idea of Woody’s legacy alive,” says Michael Sinks, the center’s board president. “This was where he kind of formed himself. He read every book in the Pampa library. This is where he got the basis, I think, for what started his career as a songwriter and a man for the people.”

There’s no doubt that Pampa and the Dust Bowl influenced Woody, just as the time period did everyone else who lived through it. Woody weathered the dust storms in a shotgun shack in Pampa, and later had this to sing about:

“A dust storm hit, and it hit like thunder. It dusted us over, and it covered us under; blocked out the traffic and blocked out the sun, straight for home all the people did run. … So long, it’s been good to know you. This dusty old dust is a getting my home. And I got to be drifting along.”