Photo by J. Griffis Smith

“Companions in arms!” proclaimed Texas patriot Juan Seguin as he prepared to bury the ashes of Alamo defenders in February 1837, nearly a year after Texas had won its independence from Mexico. “With the venerable remains of our worthy companions as witnesses, I invite you declare to the entire world, “Texas shall be free and independent, or we shall perish in glorious combat.”

The memory of battle held strong in Texans’ minds as Seguin and others from San Antonio honored the Alamo heroes. Though conflicts between Texas and Mexico began as early as 1826, the Texas Revolution’s most decisive events took place between October 1835 and April 1836. Those seven months tell a story of tragedy, courage, and larger-than-life participants as bold and dramatic as any in human history.

The Texians (a pre-statehood term for Texas citizens) revolted against Mexico when General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna and his supporters revoked Mexico’s Federal Constitution of 1824 and tried to block immigration to Texas colonies, increase tariffs, restrict access to arms, and-truth be told-outlaw slavery (though the Mexican peonage system differed little from slavery).

“The Texas Revolution should be seen as part of an ongoing Mexican civil war;’ explains Bruce Wmders, curator and historian at the Alamo, noting that other parts of the Mexican republic also rebelled after Santa Anna seized power in 1833 and exerted dictatorial rule.

Today, the Texas Historical Commission helps preserve and interpret the Texas Revolution story by designating the sites where the events transpired as the Texas Independence Trail Region. The region, which is part of the commission’s Texas Heritage Trails Program, covers 28 counties throughout southeast Texas and stretches from the Gulf Coast inland to San Antonio, and Bastrop and Washington counties. Exploring the sites and their wide range of activities-from battle reenactments to museums and missions-brings to life the influential time period for history buffs and sightseers alike.

We’ll commence our trail trek at Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site, 14 miles north of Brenham. Fifty-nine delegates gathered in Washington-known as “the birthplace ofTexas”-in early March 1836 to adopt the Texas Declaration of Independence.

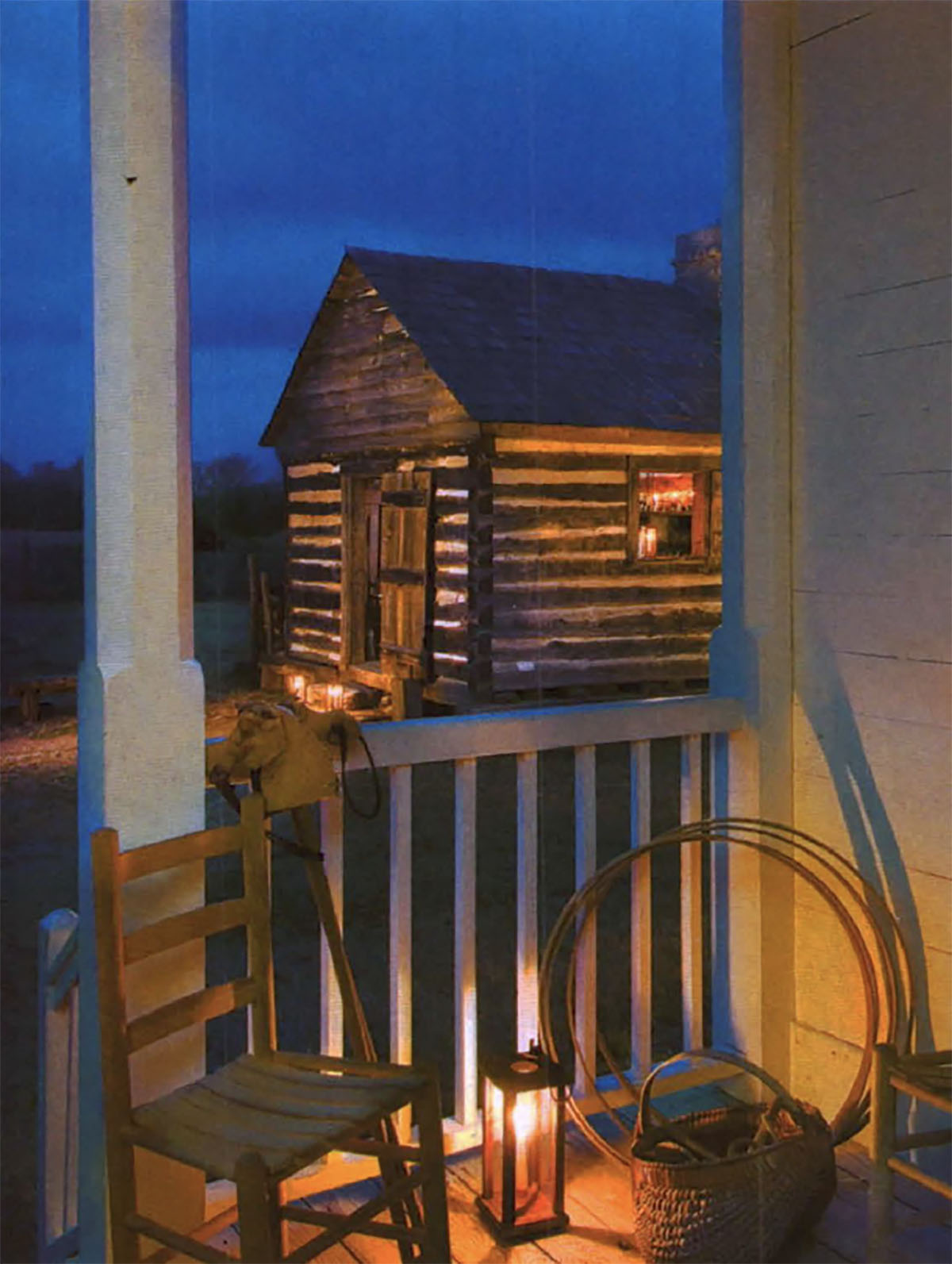

The 293-acre site includes a replica of Independence Hall, where the declaration was signed, the Star of the Republic Museum, the Barrington Living History Farm, and a visitor center and gift shop. The reconstructed Independence Hall stands on the same ground once occupied by the historic structure. Bill Irwin, Washington-on-theBrazos park superintendent, says archeologists determined the location of three of the old hall’s corner posts during a 1968 dig. ”We were able to place the replica in the same location as the original, which was built as a warehouse, and make it equal in size,” he explains.

Flags at The Alamo

With the site’s rural setting, it’s easy to imagine the delegates’ tent lodgings and the long-vanished taverns and inns that made up the town. And it only takes a minor flight of fancy to picture Sam Houston dressed in buckskins, celebrating the formal declaration with eggnog.

Along the Brazos River at the state historic site, you can ponder the past under the shade of La Bahia Pecan Tree. The towering pecan takes its name from La Bahia Road, a trade route from the 18th and 19th centuries that crossed the Brazos River at Washington. Seneca McAdams, executive director of the Texas Independence Trail Region, notes that folks can grow their own living symbols of Texas Independence history. “The tree was here in 1836:’ she explains, “and the Washington-on-the-Brazos State Park Association is selling seedlings of the tree.”

At the Star of the Republic Museum, you can see how the Convention of 1836 may have looked, as depicted in Reading of the Texas Declaration of Independence, a 1936 oil painting by Charles and Fanny Normann. ”We’re the only museum that focuses on the 10-year period of the Republic,” says museum Director Houston McGaugh. Some 6,000 artifacts and documents, including a Republic of Texas passport, chronicle life in the Texian nation.

While the village of Washington hosted the convention that formally declared independence, the town of Gonzales, on the Guadalupe River 95 miles to the southwest, became the ”Lexington of Texas” as the site of the revolution’s initial skirmish. First settled as the capital of empresario Green De Witt’s colony in 1825, Gonzales was the westernmost of the Texas colony towns and the closest to San Antonio de Bexar, the Mexican capital of the Department of Texas, part of the larger state of Coahuila y Tejas. In 1831, DeWitt asked for a cannon to protect Gonzales from Native American raids, and Mexican officials loaned the colonists a Spanish-made six-pounder.

As tensions mounted in 1835, Mexican dragoons rode to Gonzales from San Antonio to retrieve the artillery piece. Colonists refused to surrender the cannon and, on October 2, engaged some 100 soldados in the brief Battle of Gonzales. The Texians commemorated their cause by making a battle flag from a wedding dress, featuring the now-well-known image of a cannon beneath a star and the slogan “Come and Take It.”

The Gonzales Memorial Museum, built during the Texas Centennial in 1936, today houses a cannon some believe to be the “Come and Take It” cannon. The Come and Take It Festival, held on the first full weekend in October, includes a reenactment of the Battle of Gonzales. During the event, actors representing Texian volunteers and Mexican soldados square off, wearing period attire and firing blanks from authentic weaponry, including a standin for the “Come and Take It” cannon. The battle rages after a meeting between the two sides’ leaders proves fruitless and the Texians holler, “Come and take it!”

About 60 miles south of Gonzales sits Goliad and Presidio La Bahia, a fort built along the San Antonio River in 1749 that later became a key battleground in the Texas Revolution. On October 9, 1835, a week after the Gonzales skirmish, Texians attacked and took over the Mexican military installation of Presidio La Bahia. “That was important because it cut San Antonio off from the nearest port-Copano down on the coast,” says Presidio La Bahia Director Newton Warzecha. The presidio chapel is still an active church, and overnight visitors can rent the presidio’s captain’s quarters, a two-bedroom apartment with a living and dining room.

Of course, the events that seared the Texas Revolution into global, historical consciousness took place in San Antonio, the seat of Spanish, and later, Mexican government in Texas. After the Battle of Gonzales, volunteers continued to swell the Texian army ranks. The Texians, led by Stephen F. Austin, made their way to San Antonio, where General Martin Perfecto de Cos had occupied the city with 750 Mexican soldiers. On October 28, 1835, the Texians engaged Cos’ forces in the Battle of Concepcion at the then-deserted mission of the same name. The mission, dedicated in 1775, is now part of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park.

Other minor skirmishes punctuated a standoff until December 5, when Benjamin Rush Milam could wait no longer. “Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?” he reportedly implored. Milam led the volunteers into several days of intense battles through the city’s plazas and streets before he was killed by a sniper’s bullet outside the Veramendi Palace. On the morning of December 9, General Cos surrendered. The Texians occupied the Alamo, and the Mexicans were allowed to withdraw south.

A couple of months passed before the Mexican army returned, this time under the direction of Santa Anna himself, the self-styled “Napoleon of the West.” A garrison of only some 200 men remained within the Alamo walls when the 1,500-strong Mexican army arrived in late February. Another 1,100 soldados joined the Mexican army just days before the final assault. No Texas rebels urvived the dawn battle on March 6, 1836, as Santa Anna kept his word that “no quarter” would be given.

Today, the old stone church of the Alamo, built in the 1750s, stands as a shrine to liberty, its weathered parapet, added in 1850, recognizable throughout the world. Having visited the site myself dozens of times over the last half century, I am humbled and awestruck anew each time I return.

“Visitors are understandably drawn to the front of the church,” says Winders, the Alamo curator. ”But in the tours we give, we explain that the church was only part of the compound, and we point out locations of the walls and other structures!’ Winders notes that the Alamo still has secrets to unravel. ”We have a conservator cleaning the stones and assessing the church’s needs for ongoing preservation. Recently, she uncovered a Spanish Colonial window or archway that we hadn’t known about before.”

Alamo survivor Susanna Dickinson informed Sam Houston of the loss on March 11, 1836, in Gonzales, where he was gathering the Texian army to join the fight. Hearing that Santa Anna was headed east with his massive force, colonists hurried toward the Sabine River in a flight called the ”Runaway Scrape;• burning their homes and goods so the Mexican army could not make use of them. Houston and his fledgling army retreated as well.

One of the towns that burned during the Runaway Scrape was San Felipe, the capital of Stephen F. Austin’s colony and the seat of Texas’ provisional government. Today, the San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site-about 50 miles west of Houston on the Brazos River-includes a visitor center in the 1847 Josey General Store and a bronze statue of Austin created in 1936. At the visitor center, you can learn about the local printing press that printed the Texas Declaration of Independence, and peruse informative displays on surveying and archeology.

The Texians’ retreat continued, and the Goliad area once again took center stage in the unfolding drama. On March 20, 1836, the Mexicans defeated a Texian force under Colonel James Fannin at Coleto Creek near Goliad “The Texians surrendered thinking they would be treated as prisoners of war;’ Warzecha explains. ”But on March 27, the Mexican army executed 342 men. We reenact the Goliad Massacre each year on the weekend closest to March 27.”

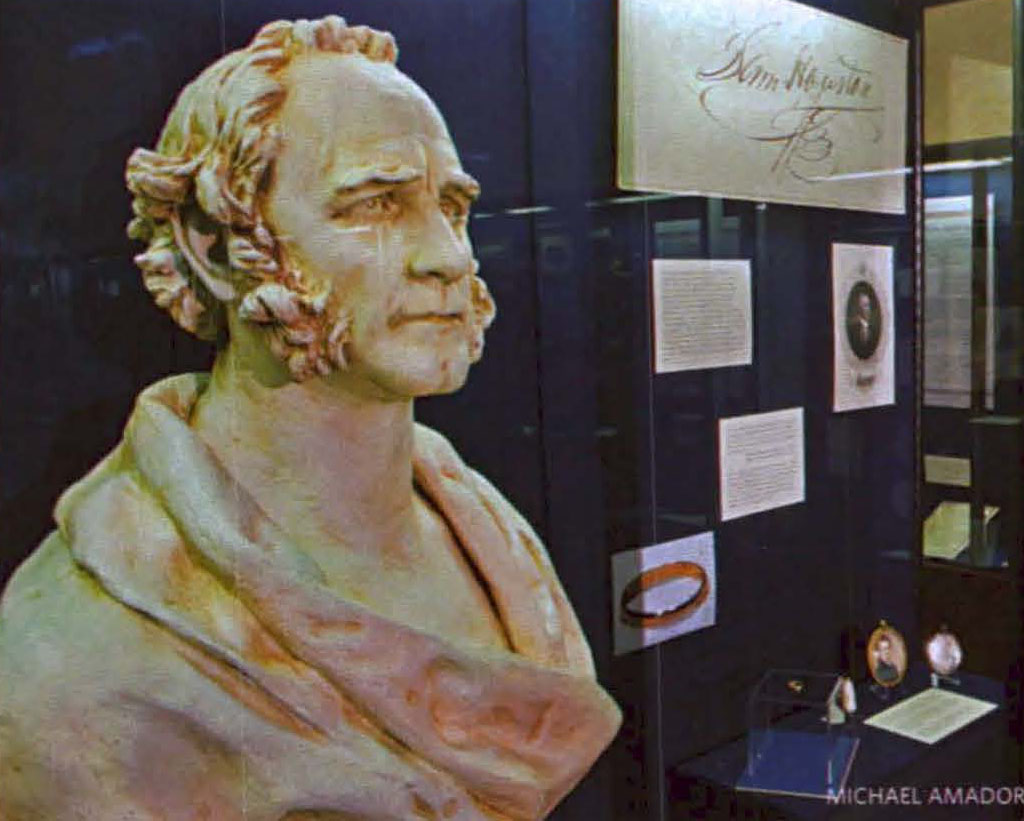

The Goliad Massacre fueled the fire of Texian rebellion, which climaxed at San Jacinto-site of the San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site-on April 21, 1836. On that day, Sam Houston’s army charged across the plain to engage the Mexican force, shouting ”Remember the Alamo!” and ”Remember Goliad!” Colonel Juan Almonte surrendered for the Mexican army after a furious 18-minute battle, but the Texians continued to pursue fleeing Mexican soldiers for hours. “Gentlemen! Gentlemen!” Houston was reported to have implored of his men. ”I applaud your bravery but damn your manners!” Houston was merciful when a captive Santa Anna was brought before him, sparing the Mexican general’s life and eventually allowing him to return to Mexico.

Today, the 1,000-acre San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site features a 570-foot-tall obelisk of concrete, steel, and limestone, topped by a 220-ton lone star. The monument’s base houses the San Jacinto Museum of History and the Jesse H. Jones Theatre for Texas studies.

Since 2002, the nonprofit San Jacinto Battleground Conservancy has been working to acquire adjacent acreage that was part of the battleground, restore the battleground to its 1836 condition, and foster research and educational programs about the site. Conservancy Vice President Jeff Dunn says the group sponsored a 2009 archeological project that identified the location where Colonel Almonte surrendered to Sam Houston’s army. The spot remains the property of a nearby power generation plant. However, the archeologists were granted access and found hundreds of musket balls and other metal Mexican army artifacts, including intact bayonets.

Intermittent hostilities continued — the Mexican army invaded and briefly held San Antonio twice in 1842-and the Rio Grande was not firmly established as the international border until the U.S.-Mexican War ended in 1848. But the Battle of San Jacinto clearly affirmed the prophetic words written on December 27, 1835, by Jose Francisco Ruiz, one of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence. “Only God;• he wrote, “could return Texas to the Mexican government” His words reflected the remarkable resilience and fortitude of the Texians-characteristics still on display in the Texas Independence Trail Region.

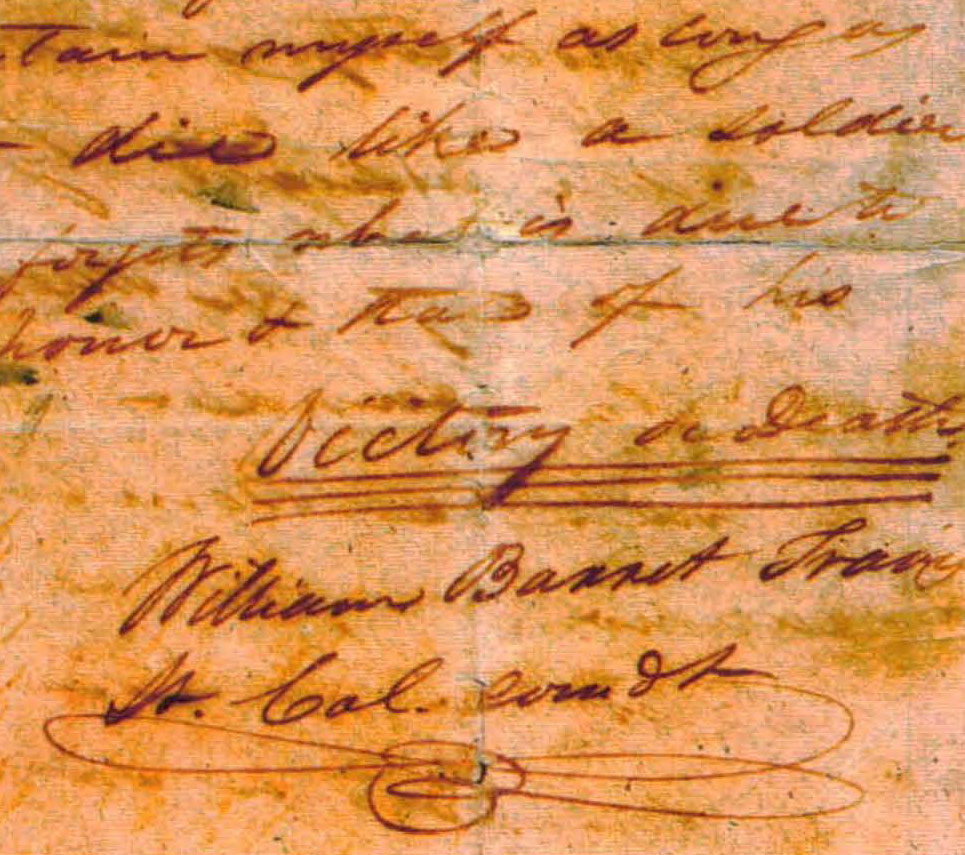

Return to Sender—The Travis Letter

The Alamo is presenting a rare opportunity to see a letter penned by William Barret Travis during the siege of the Alamo. Travis, the Texas commander at the battle, sent the letter by courier on February 24, 1836-10 days before his death-to draw reinforcements from the Texas colonies and win support from the United States. The letter, which is normally housed at the Texas State Library and Archives, has now returned to the Alamo for the first time in 177 years and is on display from February 23 to March 7.

Travis addressed the two-page document to “the People of Texas and all Americans in the World.” Travis penned that the Alamo garrison was “besieged by a thousand or more Mexicans” and had “sustained a continual bombardment and cannonade for 24 hours.” Affirming that all would be “put to the sword” if the Alamo fell, Travis vowed that he would never surrender and underlined his closing pledge, “Victory or Death,” three times.

In a postscript, Travis noted one stroke of worldly good fortune. When the enemy first appeared, he wrote, the Texans had less than three bushels of corn, but since had located 80 or 90 bushels and “got into the walls 20 or 30 head of beeves.”

A ring belonging to Travis, one of his childhood poetry books, and other personal items are also on display with the letter.