Fifty-two African American men served as Texas legislators during the Reconstruction era that followed the Civil War. Though these representatives came from diverse backgrounds and accomplished much as lawmakers, most share a common distinction today: anonymity.

The absence of 19th-century Black elected officials from many history books belies their importance. Collectively, they represented the first significant political achievements by Black Texans. The group included farmers, builders, lawmen, teachers, merchants, and preachers. Most of them were literate, which is notable considering the majority had been enslaved. And, all were Republicans—the party of Abraham Lincoln—in a state where secessionist Democrats had aligned with the Confederacy.

The key to African Americans’ political ascension in Texas was Reconstruction, the federal government’s post-Civil War effort to rebuild the South and protect the rights of emancipated Blacks. This included the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, which gave Black men the right to vote. (Women of all races remained disenfranchised until the 20th century.)

Most of the Black legislators “served only two terms at most, so we associate few major accomplishments with them,” says historian Carl Moneyhon, professor emeritus at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and author of George T. Ruby, Champion of Equal Rights in Reconstruction Texas. “Consequently, they fall between the cracks when history is written. When you are overlooked, you are also forgotten.”

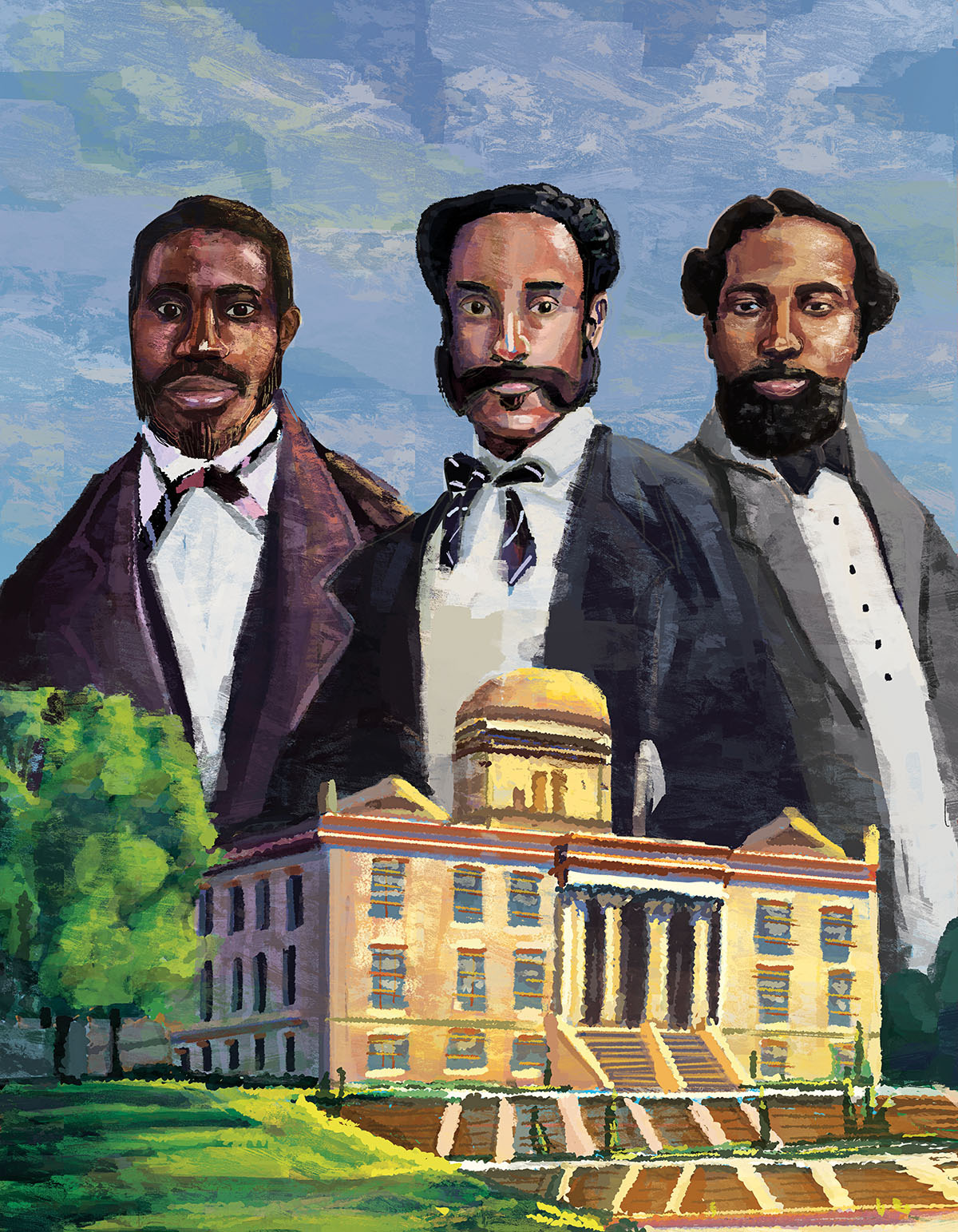

Though you may not have heard their names, these three Black lawmakers—George Ruby, Walter Moses Burton, and Matthew Gaines—represent a momentous first step in the state’s recovery from slavery. As the abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote in May 1865, “Slavery is not abolished until the Black man has the ballot.”

George Ruby,

The Politician

Born in New York in 1841, George Ruby was one of the few African Americans living in Texas in the late 1860s who was born free. He grew up in Maine, the son of abolitionists, and as a young man traveled to Haiti to work as a reporter for an abolitionist newspaper.

Ruby moved to Louisiana in 1864 to teach, but within two years, he fled to Texas after a mob of white men beat him for trying to open a Black school. Living in Galveston, Ruby taught school, wrote for newspapers, and worked as an agent for the U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau, which oversaw affairs related to freed slaves.

By 1868, when he was 28, Ruby was a rising star in the Republican Party and secured a seat as the only Black delegate from Texas to the Republican National Convention. He was also chosen that year as a delegate to the state constitutional convention, which rewrote the Texas Constitution to bring it in line with Reconstruction policies. A year later, Ruby won a seat in the Texas Senate, representing Galveston, Brazoria, and Matagorda counties—all mostly white.

Ruby has been heralded as the preeminent Black politician in Texas during Reconstruction in terms of power and ability. He wrote laws to incorporate railroads and insurance companies, and to conduct geological and agricultural surveys of the state. He also organized the Labor Union of Colored Men in Galveston to benefit dock workers.

“The real importance of men like Ruby cannot be measured in such terms of accomplishments,” Moneyhon said. “Ultimately, the fact that in a society where Black men had never been allowed a public voice, men like Ruby stepped forward to press for programs that would benefit his own race and indeed all people of Texas, even in the face of threats of violence, and that’s what makes him distinct and a real hero.”

Ruby chose not to run for office in 1873 and moved to New Orleans where he edited a Black newspaper. He died there of malaria in 1882.

Walter Moses Burton,

The Sheriff

Of the four Black men to serve in the Texas Senate during Reconstruction, Walter Moses Burton served the longest. His four terms covered 1874 to 1882, and he would be the last African American to hold one of those seats until Barbara Jordan’s election in 1966.

Born into slavery, Burton was brought to Texas at age 21 from North Carolina by his owner Thomas Burton. Thomas taught Walter to read and write and sold him large parcels of land after the Civil War, making Walter Burton one of the richest men in Fort Bend County.

Burton entered politics in 1869 when he became the first African American to be elected a local sheriff in the U.S. As was common during segregation, only his white deputy was allowed to arrest white lawbreakers. Four years later, in 1873, Burton was elected to the Texas Senate, representing Austin, Waller, Wharton, and Fort Bend counties.

In his book The Negro In Texas, 1874-1900, historian Lawrence Rice described Burton as “tall, well proportioned and with broad shoulders, very black, and with a set of whiskers which turned gray in later years, giving him an air of dignity.” Burton’s wife, Abby “Hattie” Jones, may be more well known than her husband. In 1871, she survived being tossed from a moving train after refusing to leave the “whites only” car.

Burton focused on education, pushing for free public schools for all. In 1876, Burton joined fellow Black legislators in support of a bill to create the “Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for Colored Youths,” which today is Prairie View A&M University.

More than a century after his service, an elementary school in Fresno was named in Burton’s honor; and earlier this year, Fort Bend County paid tribute to his legacy with a portrait placed in the courthouse. Eric Fagan, who was elected in November as the county’s first Black sheriff since Burton, attended the unveiling in February. “One reason that I’m standing here is because of men like Walter Moses Burton,” he said in a Houston Chronicle story about the event.

Matthew Gaines,

The Minister

Matthew Gaines was the opposite of his counterparts Ruby and Burton. Where Ruby was tactful and Burton was conciliatory, Gaines was confrontational; where Ruby was diplomatic and Burton was amiable, Gaines remained aloof.

Born into slavery in 1840 in Louisiana, Gaines was sold to a Robertson County planter in Texas in 1859. After emancipation in 1865, Gaines settled in the Blackland Prairie town of Burton as a farmer and became a community leader through his work as a minister. He won a seat in the Texas Senate in 1869.

He entered the Senate reputed to be “dull, plodding, and an ignorant ass,” according to Merline Pitre, a history professor at Texas Southern University and author of Through Many Dangers, Toils and Snares: The Black Leadership of Texas, 1868-1898. However, Gaines would prove his naysayers wrong. As Pitre wrote, Gaines quickly put his colleagues on notice: “I am not afraid to speak a single word on this floor, the consequence of which I [never] afterward shall shrink from.”

Thus began the controversial career of Gaines, who proved to be a thorn in the hides of both Democrats and his fellow Republicans. Ruby called him a “bum,” yet Gaines stood as a proud, outspoken advocate for the African American community and a staunch supporter of education and building the militia.

Both parties sought to oust Gaines, finally succeeding after he was found guilty of bigamy in La Grange. The Texas Supreme Court sided with his appeal, however, and Gaines won his seat back. The win was challenged by Gaines’ white opponent, who accused him of being a felon, though the charge had been reversed. Still, in March 1874, the Senate Committee on Election and Privileges removed Gaines from office.

While his service was tumultuous, Gaines was a passionate supporter of Texas’ adopting the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862, enabling the creation of Texas A&M University in 1876. The act granted land to states to build colleges that focused on agriculture, mechanical arts, and military tactics. A long-awaited statue of Gaines will be unveiled on the College Station campus this fall.

Reconstruction’s bold attempt at interracial democracy came to a halt in 1873 as the Republican Party’s power—and the number of Black voters and legis-lators—drastically declined. That year, Republican Gov. Ed Davis was soundly defeated by Democrat Richard Coke. Back in control, Democrats flexed their power by instituting a poll tax and a whites-only primary. The last of the Reconstruction-era Black legislators left office 24 years later in 1897. Pitre said of the men: “It appears that the novelty of those Black politicians was not merely that they got elected to office, but that for nearly a quarter of a century they weathered the storm.” Then, they were forgotten by time.

But the names and legacies of the 52 Black men who became legislative leaders in post-emancipation Texas are slowly resurfacing because of growing interest in Black history among historians and society at large. Together, they’re bringing the untold stories of Black Texans to the fore and keeping their memories and deeds alive.