Gentle, peach-toned light beams from a thin slice of roof hovering over the grass-covered pavilion on the campus of Houston’s Rice University. We approach the glow in pre-dawn darkness, dodging sprays from the lawn sprinkler.

Turrell in Texas

Find more on artist James Turrell at jamesturrell.com. The following are installations/shows included in the story; check the websites for hours, showtimes, and reservation requirements.

Twilight Epiphany, Rice University, next to The Shepherd School of Music, 6100 Main St., Houston.

The Light Inside (tunnel), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1001 Bissonnet St., Houston.

The Color Inside, University of Texas Student Activity Center, 2201 Speedway, Austin.

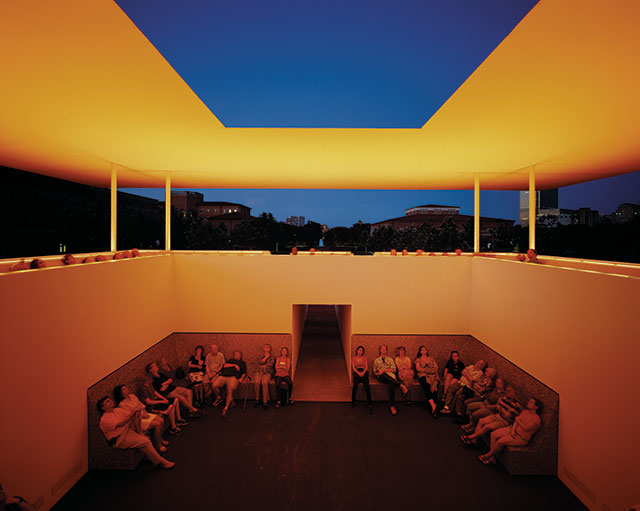

Eager to drink in the art installation, forged from light and the sky itself, we enter through a tunnel at the edge of a pyramid-shaped edifice designed by artist James Turrell, who calls it a “Skyspace.” We take a seat on an inexplicably comfortable pink granite bench directly under a 14-by-14-foot square aperture in the roof.

At 5:40 a.m., the show, called Twilight Epiphany, begins. We gaze up at the dark sky through the square hole. As the peach-toned LED light at the edges of the roof changes to rose, then white, the square of sky above us begins to slowly take on different hues. It looks bluer or blacker, then a bit purple.

In the hands of James Turrell, the sky’s color eludes definition. Our brains play with us as computer-controlled light slowly evolves through the entire color spectrum, playing off the light of breaking dawn. The sky we see through the square morphs from pink to violet to robin’s egg blue. The closer we get to true sunrise, the more intense the colors become. After awhile, the square seems opaque: deep azure, forest green.

“I create the context of seeing,” explains Turrell, who lives in Arizona. “I’m really interested in this elixir called light. We drink it as Vitamin D through our skin, so there’s a physical quality. Then, there’s a psychological and emotional quality where people respond to light almost like tone in music. Then there’s the spiritual aspect.” People talk about their response to Twilight Epiphany, he says, as a true epiphany.

“I create the context of seeing,” explains Turrell, who lives in Arizona. “I’m really interested in this elixir called light. We drink it as Vitamin D through our skin, so there’s a physical quality. Then, there’s a psychological and emotional quality where people respond to light almost like tone in music. Then there’s the spiritual aspect.” People talk about their response to Twilight Epiphany, he says, as a true epiphany.

As the sun peeks over the horizon, Turrell’s dawn moves far beyond rosy-fingered into a deep mauve against blue LED light. Then the light itself turns rosy, and the square becomes vibrant turquoise. After about 40 minutes, as a bird flies over the aperture, the LED light returns to faint orange, the ceiling fades to white, and the sky, once again, is blue. The show is over for now.

People talk about “experiencing” art all of the time, but, mostly, we just gaze at it. Turrell’s Skyspaces—more than 80 of them awe audiences worldwide—truly pre-sent experiences. That might well be why the 71-year-old, white-bearded Turrell has become one of the most talked-about artists on the planet right now, and why, in July, President Obama awarded him the National Medal of Arts.

Texans are in luck: There are currently three permanent Turrell public installations to visit—two in Houston and one in Austin.

The Rice University Skyspace offers its experience daily at sunrise and sunset, peak times for the sky’s natural light show. Daybreak adds the advantage of quiet, with fewer people and cars about. Both spectacular shows cost nothing to see. Required reservations at the dusk show ward off overcrowding. Twilight Epiphany seats 120 on two levels, and acoustical engineering enables live or piped-in music to occasionally enhance a light show.

“People ask me if I get tired of going out there,” says Hiram Butler, whose Houston gallery represents Turrell. “I say, ‘No,’ because I see something different every time.”

The weather, as well as cloud cover and even the proximity of the sun and phase of the moon, can affect a Skyspace experience. We saw evidence when a gentle rain fell during our visit to the second Texas Skyspace, called The Color Inside, on the University of Texas campus in Austin. The colors were muted, but still well-defined as we watched LED lights change the sky through the oval hole in this smaller Skyspace, which accommodates about 25 people on a circular bench. Light bounced off the droplets as they fell in a circular curtain, and a slight splash of rain added an organic element to the experience, making us feel a part of the work.

Perched atop the three-story UT Student Activity Center, this Skyspace was commissioned after UT students said they wanted a place for meditation. It’s open for contemplation all day long, but its free, 40-minute light show, like Rice’s but more intimate, occurs at dusk (and occasionally at dawn).

Because of Skyspaces’ sensitivity to ambient light, Turrell works hard to choose sites with minimal invasion from other light sources. Sometimes, though, other buildings do rise after his works are finished. When a high-rise condominium with a highly reflective exterior went up directly next to Dallas’ Nasher Sculpture Center, which offered a Skyspace in its garden, the resulting refraction rendered the piece ruined, in Turrell’s estimation. Now closed, the small Skyspace has been redesigned with a raised, tilted roof that would ameliorate the problem, and it can be rebuilt and reopened to the public if the Nasher and neighboring condo developer can agree on who pays for the change, Butler says.

Another Skyspace at the Live Oak Friends Meeting House in Houston has been closed for more than a year because a plumbing leak damaged the wood floor. Himself a Quaker, Turrell has approved the new floor, but it hasn’t yet been built. Once it is, the public will get to view this Skyspace again. This one doesn’t feature an illumination with colored LED lights but is more of a stylized, square skylight with a retractable cover in the curved roof, designed to involve light in the experience.

Turrell’s work involves more than his signature Skyspaces, and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, owns more Turrell creations than any other museum in the nation. The museum occasionally mounts major Turrell shows, but it contains one permanent installation in the tunnel linking its two buildings beneath Main Street.

Called The Light Inside, the tunnel—the first permanently installed, publicly accessible Turrell piece in the country—offers visitors a walkway through a neon-lighted, 118-foot passage whose color is constantly changing: a sort of light-bracketed catwalk. I stopped at its center, experiencing the change of energy in the tunnel—a blue light felt calming; a red, slightly agitating. Other visitors passed by, occasionally extending an arm to see if a wall existed on each side of the walkway. There’s no wall, but the light provides an illusion of a wall. Like other walk-through Turrell installations, this one can be a bit disorienting because of that effect. The light cycle lasts 24 minutes and, Butler says, is among the most popular works at the museum.

“Museums always say their toughest audience is adolescent boys,” Butler says. “Here, they flock to the Turrell tunnel.”

Butler calls my attention to the tall, glass rectangles at each end of the tunnel. The glass reflects the color as well, and after we’ve been in the tunnel for a bit, watching the colors change, the sides of those glass rectangles appear to shimmer with colors contrasting with their centers.

“They look like Rothkos,” Butler observes, referring to artist Mark Rothko, who used thinned paint to create floating rectangles of color on canvas. It’s all about perception, “using light as a material to explore the medium of perception.”

Our perception, then, becomes one of Turrell’s tools. If the sky is blue, “it’s our response that makes it blue,” the artist says. “We award it its color, and that is changeable.”