The Long Way Home

A son’s wanderlust leads him back to his family

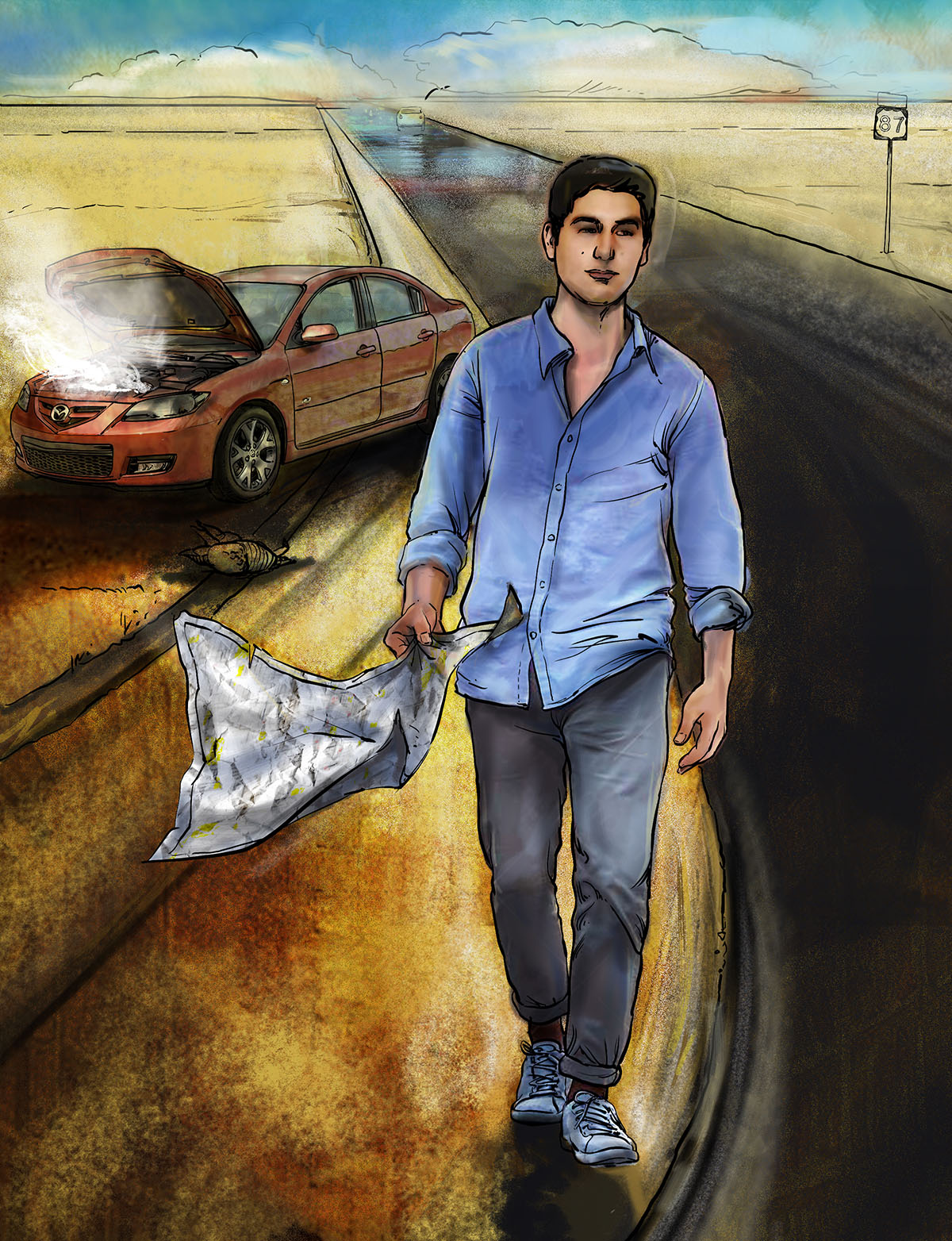

I was enjoying an aimless drive down US 87 on a sunny October afternoon when my engine started to sputter. I had been listening to Lucinda Williams’ album Car Wheels on a Gravel Road and feeling the kind of thoughtless calm only the open road can inspire, the warm fall air rushing in from the open windows of my Mazda sedan. Just when Lucinda was about to lay into the chorus on “Drunken Angel,” a slow mist of black smoke started creeping from under the hood, blighting the clear and cloudless afternoon. The wheel locked. I steered the car toward the shoulder, barely managing to get it off the road, before the engine stalled. That’s when I discovered I was out of cell service.

I had finally gotten what I wanted: I was hopelessly lost.

Caught between exhilaration and panic, I wondered how I would get back to my college dorm. It was the fall of 2008 and I was a freshman at St. Edward’s University in Austin, some 150 miles east of where I’d broken down. I hadn’t seen another car for miles, only the lonely two-lane highway and what had once been a chunky armadillo, who was lying face up nearby. Watching the smoke plume from the hood, I remembered the old road map my parents had gifted me when I turned 16. I dug in the glove box and found it under a speeding ticket and a bag of melted Now and Laters. But I was a ’90s kid, a child of the internet age—I had no clue how to use a map. I unfolded it on my lap and surveyed the multicolored lines indicating various highways. They wound in every direction, in and out of towns I’d never heard of, like an endless spool of yarn.

Sweat pooled on my eyebrows and I stepped outside for some fresh air. As I was about to spread the map on the hood to take a better look, a gust of wind caked my eyes in dust. I squinted at my phone. Still no service. I considered doing the unthinkable and opening the hood to investigate what was wrong. I almost had to laugh. Here was everything I knew about cars: They go. I looked down at the armadillo, whose little black eyes were frozen open and staring back at me. No doubt, he would know where we were.

Wherever I’d ended up, I was a long way from where I was supposed to be. Back in Austin, my biology classmates were attending a lecture on the history of migratory birds in Texas. I was feeling defeated, but I could still appreciate the irony: I’d skipped a lesson on the masters of navigation and had gotten myself lost on the side of the highway. As I wiped dust from my face, it occurred to me that before today I’d never been lost in my entire life. I was raised in central Houston, surrounded by asphalt and office buildings, rarely more than 15 minutes from my childhood home. For the past few weeks, though, I’d been skipping my classes and wandering Central Texas in my little sedan, hoping the country air would be healing after what had been a difficult few months.

A mud-covered trailer barreled past, and I offered a half-hearted wave for help that went unnoticed. Determined to find my way, I traced the highway on the map with my finger and spotted a town I remembered passing a short time ago: Melvin. That meant the city of Eden was probably only a couple of miles west of me. I decided to walk it. I looked down at the car baking in the sun, smoke still radiating from under the hood, and thought of my father. This would be another reason to avoid his weekly call.

I folded the map in my pocket and thanked the armadillo for his company. The wind blew another cloud of dust past as I left the car, but this time it fell against my back, gently nudging me away from the afternoon’s misfortune. As I ventured toward Eden, my stomach grumbled and I realized it had been hours since I’d eaten. Surely a town named after an earthly paradise would have a Dairy Queen.

A few months before I left Houston for college, my father was diagnosed with stage 4 lymphoma. The cancer was aggressive, and by the time he was diagnosed, it had already spread to his lungs, kidneys, and bone marrow. I was crushed. I finished my senior year of high school in an anxious haze, keeping news of his diagnosis from even my closest friends. My dad urged me to focus on school and not to worry about him too much. He said he felt strong and was hopeful to make a full recovery. But soon his body betrayed his words. He began chemotherapy and started losing weight, slowly at first and then more dramatically. Eventually, his clothes stopped fitting and hung from his body like hand-me-downs. His hair—still jet-black in his late 50s—turned a lifeless gray and came out in clumps, clogging the shower drains and littering the bathroom floors.

From my bed, I could hear him struggling to sleep at night, coughing so loud and hard I could feel the sting in my chest from the next room. I tried to drown out the sound with music, but it was no use. It was impossible to avoid what was happening to him.

I was relieved when it was finally time to leave for school. I didn’t want to be around for what came next. I didn’t want to see my father wither into nothing, see him taken from me so cruelly.

That fall I began as a freshman at St. Edward’s. I was eager for a new start somewhere far from my family, somewhere I wouldn’t be constantly reminded of illness and the threat of death. The university sits atop a grassy promontory overlooking downtown Austin, where I could see the entire city on a clear night. The grounds span almost 160 acres and are covered with sprawling live oaks and Ashe juniper that bend and twist above students’ heads as they walk to class. The walkways are lined with cypress trees and ancient bur oaks, some of which were standing when the school was founded in 1877. It’s one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen.

The gem of the campus is the main building: a four-story Gothic Revivalist tower with minaret-like turrets and soaring limestone arches, like something out of a Victor Hugo novel. Built in 1903 after a fire destroyed the original tower, the main building has sat uphill from Austin for more than a century. At night I liked to walk along the courtyard beside the tower, in awe of the beauty and stillness of my new home. I liked to imagine they would still be there in another 100 years: the trees and the hills and the tower. It was a comfort to know that some things are permanent.

Most days my thoughts drifted to my father. While my friends were going to parties and falling in love, I shut myself in my dorm and listened to old records. I questioned whether I should’ve left Houston while my dad was sick. I avoided calls from my parents, fearing what news they would bring about my father’s illness.

After a sleepless night, I decided something needed to change. I hadn’t been to some of my classes in weeks and was sinking into depression. I decided to skip my English workshop and head south from campus to see if a short drive would make me feel better. I have always loved driving. From the moment I turned 16, I’ve felt an ease and peacefulness behind the wheel that I don’t feel anywhere else. Sometimes after a bad fight with my parents, I would get in my rusty Mitsubishi and drive in circles around my neighborhood. In those moments, brimming with anger or sadness, the feeling of the car moving against the road was enough to calm me.

As I traveled on State Highway 71 that morning, the sun bathed the road in stripes of pink and sherbet orange. The warmth on my face comforted me. Something about the colors and look of the clouds reminded me of the cover of Harry Nilsson’s album Aerial Ballet, and I dug through my CDs to find my copy. I must have been feeling sentimental because I played Nilsson’s “I Said Goodbye to Me,” loudly singing the lines where Nilsson parts with his lover: I’ll leave my things behind for all to see / And hope that she will understand why. For a moment, as I sped down the highway toward nowhere, I forgot everything that had been weighing me down. I simply steered the car forward.

I kept no sense of direction. When it felt good to turn left, I turned left. When I hit a dead end, I turned around and found a new direction. After nearly an hour of wandering, I pulled into a parking lot just north of the Colorado River and walked into some place called Falls Creek Skatepark to stretch my legs. I had no idea where I was—Marble Falls, it turns out—only that I’d gone far enough for that day. I sat down in the high grass to watch some kids do tricks on their skateboards. It was nearly fall and the air was getting cooler. I closed my eyes and listened to the click-clack of skateboards against ramps and hummed the opening bars of “I Said Goodbye to Me.” I laid my head down and drifted in and out of sleep while the children laughed and called out to each other.

I repeated this routine in the days after. Each time I set off in a new direction with a single goal—to drive, with no plan or destination in mind, until I felt better, until there was lightness and ease. Initially I stayed close to school: Dripping Springs, Cedar Valley, Bee Cave. I drove to Pedernales Falls State Park and watched the sun rise over the river at dawn. I traced the bend of the Colorado River and watched largemouth bass jump in the water at Mansfield Dam and Common Fords Ranch Metropolitan Park. Sparkling lakes and cracking limestone cliffs spotted every turn of my drive. It was nothing like the Gulf Coast—nothing like my home—and I loved it for that.

For every drive there was music. Some days it was Aretha, others it was David Bowie or Band of Horses. I began to look forward to driving more than anything else. I stayed up at night and thought about where I might end up the next day. Rockdale? Canyon Lake? El Paso, 577 miles away? Maybe I would drive straight through Texas to Arizona and see the Grand Canyon. Anywhere seemed possible. I was woefully behind in my classes, but I couldn’t resist the urge. There was always somewhere new to accommodate my wanderlust.

When I went home for Christmas at the end of the semester, I told my family nothing about my travels. I’d become reckless, eschewing any responsibility that got in the way of my driving. I’d even blown my radiator on the way through Eden and owed money to a friend for the repairs. Expecting the worst about my father, I was met with good news. After months of intense treatment, his prognosis had improved significantly. His body was responding to the medicine, and he was expected to make a full recovery. For the first time in a while, I was able to imagine a life with my father, a life I didn’t have to run away from.

The mood quickly changed when my semester grades came in. My fall had been disastrous, and I was in danger of losing my scholarship. All the miles I’d traveled—the beauty and wonder of the Texas landscape—didn’t translate to my transcript. On a walk one evening, my father asked me what I wanted for myself. What did I dream of if anything were possible? I couldn’t answer the question. I’d always wanted to be an artist and a writer, but that felt so far away. I stayed up late and thought of everywhere I’d been during the fall. The shine of the water at Possum Kingdom Lake. The sound of the bright orange robins above my head walking along the Colorado River. It might take a lifetime of driving to answer his question.

Months later, on a cool March afternoon in 2009, I traveled down US 290 and spent a few hours wandering the backroads of Washington County near Chappell Hill. The rolling hills and fields of bluebonnets made me think of my mother, who was raised in the area in the late 1950s. Transplants from East Austin, her family was one of the only Mexican American ones in a town full of Polish and German immigrants. I imagined her life must’ve been strange and difficult, away from her friends and family in the city. I considered if she, too, had ever gotten the urge to leave her life behind and set off in a new direction.

This morning was different from the others. I wasn’t driving aimlessly. I was looking for Fireman’s Park, the 30-acre public green space just north of downtown Brenham. At Waterloo Records in Austin, I’d found an old copy of The Best of Peter, Paul and Mary—a favorite of my parents growing up—and it had stirred a memory from my childhood. The song “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” made famous by the folk trio but written by John Denver in 1966, had caught my ear. From the opening strums of the acoustic guitar, a hazy memory appeared.

I was 8 or 9 and driving with my father one summer morning to a baseball tournament at Fireman’s Park. Going on drives with my father was one of my favorite things to do. Our lives were so busy that it was often the only time we were alone with each other. We talked about school and the Astros, but mostly we listened to music. I loved the music he listened to, how he seemed to know the words to all the songs on the radio. We listened to oldies stations that played singers like Marvin Gaye, Carole King, and Paul Simon. The music felt like a train moving, like wind rushing against my face.

Sometimes, in the middle of a song, my father would turn the volume up and ask me to listen to a specific sound. “D’ya hear that?” he’d ask, grabbing my hand. “The thumping? That’s the bass.” When I complained I couldn’t follow—I was hopeless with rhythm—he would grab my hand and tap his fingers against my palm in synchronicity with the bass until I slowly started to track the sound.

But on that day in my memory, I was unhappy to be with my father. The night before we’d had a bad argument and I’d fallen asleep in the car the next day to protest our trip, leaving him with no one to talk with on the ride. My father, ever patient, ignored my tantrum and turned the radio on, determined to enjoy the ride. Years later, as I traveled down the highway, the sound of my father’s voice from that day flickered in my mind. Nearing the park, I remember waking to him singing gently alongside Peter, Paul and Mary: So kiss me and smile for me. His warm voice was always a comfort to me, and it had softly pulled me out of a dream. I pretended to keep sleeping so I could hear him sing a little longer. I didn’t know why, but from the moment I heard his quiet voice hum the opening words of the chorus, I stopped being upset with him.

I hadn’t thought about the song for years, but it sounded great now. It’s a song best played on your way out of town, with your loved ones at your back and the road ahead of you. For a long time, the song was associated with the Vietnam War—a lonely soldier leaving his sweetheart for battle—though Denver insisted it had nothing to do with that. He was simply lonely one evening during a layover and wrote the song to capture the feeling of being on the road—how leaving can feel like losing a loved one, like a death. As I drove, I played the song over and over, surprised at how sad it was.

More than a decade after the car ride with my father, I pulled off the same highway into Fireman’s Park, the CD skipping slightly at the second verse. The place was bigger than I remembered, the manicured fields and winding live oaks stretched deep into the land ahead. I drove past the bleachers and tried to recall anything about the long summer afternoons I’d spent there as a child. But all that came to mind was the feeling of being hot and waiting for the ball to be hit to me.

I settled into a parking spot and pulled my camera out of my backpack. When I returned to school in January, I had declared photography as my major and was enjoying classes for the first time. I loaded a roll of film and walked toward the baseball field, hoping there would be a game, but the fields were empty. I took a few photographs of the ballpark and wandered the area, expecting the scenery to jog another memory from that day. I was desperate to remember more about that afternoon. Had we fought on the way home? Had we gone to eat in town and enjoyed the evening? I strolled through the park, mostly deserted except for a few joggers, and listened to a bird singing from the top of a magnolia tree.

After about an hour I walked back to the car, disappointed I hadn’t remembered anything else, and restarted the song. If nothing else, the memory made the drive worthwhile. As I passed east through Chappell Hill, a lyric stood out to me that I hadn’t noticed before. At the end of the last verse, the tone of Mary Travers’ voice softens, and she croons wistfully: Dream about the days to come / When I won’t have to leave alone. Maybe the song wasn’t about leaving after all. Maybe Denver wasn’t thinking about his flight out of town but instead the people he was leaving and the voices that filled him with happiness.

As the song played, I switched lanes to avoid a slowdown, and then hit the gas. I was headed to Houston to meet my parents for dinner, and I didn’t want to be late.