Dust to Dust

A mother’s hope binds her family in the border town of Ysleta

I took my first post-pandemic trip in May, aboard an airplane from New York City to Texas, to visit my 85-year-old mother, Bertha Troncoso, who lives in the same adobe house she and my father built in the mid-1960s. When my mother and father and their four children arrived in Ysleta, the small town was on the outskirts of east El Paso. Back then, Ysleta was a rural community with the Ysleta Mission as its anchor, established in 1682 by Spanish missionaries and a contingent of the Tigua tribe. The missionaries and tribe were fleeing the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and their ancestral home in the Isleta Pueblo, in what is now southern Albuquerque.

Ysleta with a “Y” is where I grew up, where I went to Ysleta High School, and where my heart always returns when I need to heal, when I want to hug my mother. Ysleta is a first principle for understanding my soul—or as Aristotle would define it, a basic proposition that cannot be deducted from any other proposition. Ysleta is where I began, where I was formed. This community is at the edge of the edge of the United States, and I became an outsider and iconoclast in this country because of it. My mother belonged to the desolate landscape of Ysleta, yet she yearned to go beyond it. I admired her, yet when I left home, I knew I was traveling farther physically as well as philosophically than she ever could.

I have always loved philosophy for its wisdom beyond and maybe even against the present, and that’s also why I love Ysleta. The community seemed to exist in another time when I lived there as a child and young adult, very distinct and separate from the newer and slicker neighborhoods of El Paso. Ysleta had a different rhythm and sensibility than the big city that eventually swallowed it whole in the ’60s. Our neighborhood is about half a mile from the Zaragoza International Bridge, which was then a shoulderless two-lane bridge over the Rio Grande and a canal on the Mexican side. As a child, whenever we drove across the bridge with my family to Waterfill, Mexico, to buy garapiñados, mazapanes, queso menonita, and pinole, that canal often stunk of untreated wastewater.

Now the Zaragoza Bridge is a behemoth: nine lanes, massive inspection facilities of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and aggressive 18-wheelers entering and exiting Mexico every hour. Americas Avenue—the farm road where we used to hike for miles and hunt for snakes inside rows of cotton—morphed into a megahighway. Loop 375 now encircles El Paso, and Ysleta, and is strewn with Walmarts, Walgreenses, Pep Boyses, terminals for trucking companies, Valero gas stations, Whataburgers, and the incessant “creative destruction,” as Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter put it, of modern-day Texas capitalism. Spotting a pedestrian on any sidewalk is about as frequent as seeing a rhinoceros next to your car as you wait on the hot asphalt for the light to change.

As your car travels underneath a massive overpass and turns onto the Loop 375 ramp, you might see a mosaic depicting the three missions of the Mission Trail, one of which is the Ysleta Mission. That’s if the mosaic is not splattered with mud. In traffic, you have but a second to appreciate the reproduction of the landmark silvery cupola of the Ysleta Mission before the flow of cars pushes you forward. But if you stay on Socorro Road, which follows the river from west to southeast and avoids the highway, the real Ysleta Mission is first, the Socorro Mission follows three miles later, and finally the San Elizario Mission awaits after roughly six miles.

I have seen the changes to Ysleta whenever I return home, usually three or four times a year. But it has been over 15 months since my last visit to El Paso. Fully vaccinated, I arrive from the El Paso airport by rental car expecting to see familiar Barraca, “Shack Town,” as my side of the Ysleta neighborhood is called. The other side is Calavera, “Skeleton Town,” for the cemetery next to the Ysleta Mission. Ysleta is a working-class suburb of roughly 55,000 people with modest, somewhat rasquache homes, many made of adobe, surrounded by irrigation canals that no longer water many cotton fields. An eerie silence and emptiness also hangs in the air: The Ysleta Independent School District shut down my grade school, South Loop, this year. “Ahora este es un barrio de puros viejitos,” my mother says. This is now a neighborhood of old people.

Remarkably, as I arrive to visit my mother, the asphalt on her street has disappeared, and it’s a dirt street again. I wonder if I’m in a time warp. Mounds of dirt block my turn onto San Lorenzo Avenue. Backhoes are digging into the sand. I take another street that also leads to my mother’s house. From one side of Barraca to the other, the entire length of the street is a construction site. A giant dump truck about four SUVs long receives thunderous loads of asphalt chunks and dirt from John Deere backhoes a few feet from my mother’s driveway. Next to our house, on the dead-end street where I used to play softball, massive concrete pipes, their sections at least four feet in diameter, are stacked alongside mounds of rubble and gravel. On the sidewalk smack in front of my mother’s house, a blue-and-white stand-alone billboard announces: “El Paso Water-Eastside System Improvements: San Lorenzo CMP Replacement and Sanitary Sewer Improvements. Budget: $989,000. Scheduled Completion: Spring 2021.”

I’m shocked at the destruction/construction. How does anyone take out their cars from their driveways? Are they trapped? Still, I think it’s about time the city of El Paso invested in Ysleta and Barraca. I’d be surprised if the city has spent $900 in this poor neighborhood in the past 50 years. My mother’s small adobe house is surrounded by the upheaval.

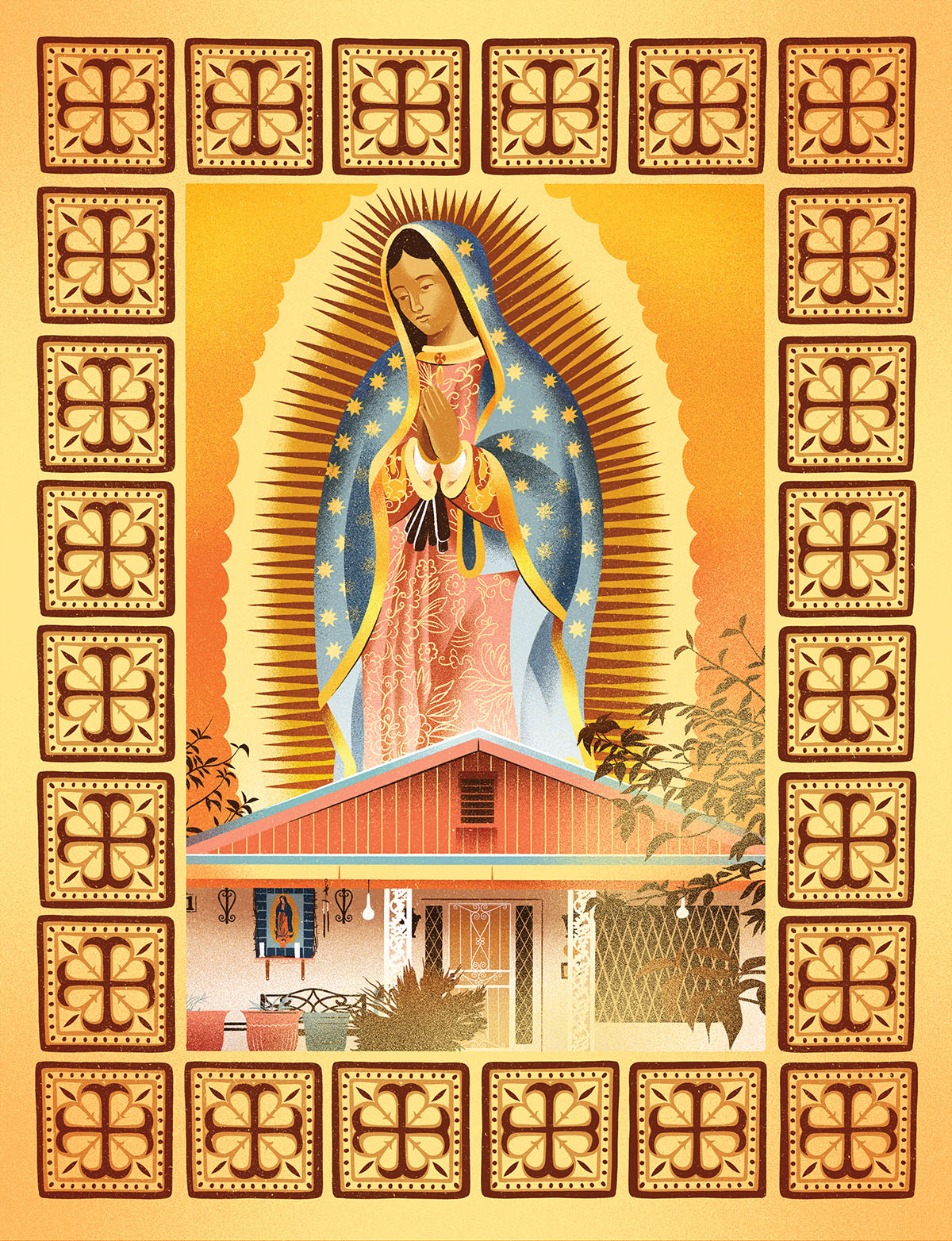

The plaster over my parents’ adobe house had been painted a yellowy white by my father years ago before he died. The bright orange wooden trim around the uneven roof is rotting at the corners. An image of the Virgen de Guadalupe, in a mosaic of Mexican tiles on the front wall, is stoic against the chaos and swirls of dust. My mother has wielded her fervent Catholicism to protect us against the evils of Ysleta and beyond.

The dirt street of San Lorenzo takes me way back. As children, my two brothers and I dug the deep trench to connect our sewer lines to the main line on the street. At the beginning of this neighborhood in the mid-’60s, everyone did this project with friends and family. Back then, that was progress. For years we’d had an outhouse in the backyard. My parents had fortified the septic field with abandoned railroad ties to keep the sand from crushing it after heavy rains. Digging the sewer-line trench meant we could have indoor toilets that flushed; we were also connecting our indoor plumbing to the newly installed water lines in Ysleta. No more driving to Abuelita’s apartment in downtown El Paso to take a bath. No more carting gallons of water for drinking and cooking for a few days in Ysleta. I remember the trench being a few feet higher than we were, and it could have collapsed and killed us all. My father, Rodolfo Troncoso, was about saving money and doing it yourself. And he was there with us every step of the way.

My sister was excluded from most of my father’s demands for cheap labor, but the three boys were expected to work until we were beyond exhausted. We were ordered to work again the next day, and the next. Project after project. The Mexican work ethic became our way of life. I always thought of my father—and his trenches; roof repairs; plumbing jobs; plastering and painting of drywall; loading and unloading of truckloads of cinderblock, brick, and lumber; the demolition of it all to destroy the old before we replaced it with the new—when I read the Nietzsche quote in grad school years later. “That which doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” That was Ysleta.

My mother is the reason we were “Americans,” as many say to the U.S. Customs agents at the international bridges when returning from Juárez, Mexico. Today she has slowly, oh so slowly, opened the orange kitchen door and locked wrought-iron screen door. Bertha turns 86 at the end of May, the date uncertain. She told me Doña Dolores Rivero, my maternal grandmother, kept changing the date near or around the end of the month. In rural Satevó, Chihuahua, in the mid-1930s, exact records were not a priority.

Today my mother’s head quivers whenever she talks, but her mind is still sharp, her memory still peerless even if it repeats a loop about this or that incident from her childhood or mine. Straight white hair touches her shoulders. Bent forward permanently, and diminutive in stature, she grips a four-pronged cane in one hand. She exhales and smiles when she touches my face. I kiss her cool, moist forehead. “Es muy triste estar sola,” she says. “Pero siempre debemos de dar le gracias a Díos por la vida.” She is alone in her house in Ysleta, with her only solace the cross around her neck. Her radio blasts the pronouncements of a Catholic preacher from Juárez.

My mother’s father died when she was three months old, and for many years my grandmother was a poor single mother who washed clothes on a rancho near Chihuahua. My mother’s stepfather, Don José Rivero—the genial man who later married my widowed grandmother with five children—found a job and a green card with “El George,” a poultry farmer in Clint who valued Don José’s work ethic. I loved my “grandfather,” who was easygoing for a man in Mexico, always funny and vulnerable. He was in many ways the opposite of the “macho” stereotype. If anyone was macho in my mother’s family, it was my tough, strong-willed grandmother, who would hit Don José on his bald head with a broomstick if he didn’t hand over his money from the farm (or later from his work as a gardener) immediately upon arriving home.

My mother was also shy and vulnerable in a way, very much like her stepfather. She didn’t fight back against my temperamental and sometimes violent grandmother. Bertha was also so beautiful she was chosen among her teenage church group, Acción Católica, to represent them in a beauty pageant. As a 17-year-old in an old newspaper photo from an event at the Casino Juárez, my mother resembled a young Elizabeth Taylor. While her stepfather’s forte was his humor, my mother’s was her intelligence and beauty. In a patriarchal society dominated not just by men but by men who were unapologetically macho, they would not have thrived. “Yo iba tener más oportunidades en Estados Unidos,” my mother says. “México era, y todavia es, muy machista.” I was going to have more opportunities in the United States. Mexico was, and still is, full of machismo. At 19, my mother crossed the river with a green card and both her parents, and she didn’t look back.

My father—my mother’s boyfriend back then—knew he would lose her if he didn’t follow her to the United States. Rodolfo had been posted at his first government job as an agronomist in Apatzingán, Michoacán. But my father hated his career and his father, Santiago Troncoso, who would only pay for agronomy school in Juárez. Also, Rodolfo had heard chisme from one of his sisters that his girlfriend—my mother—had been seen dancing at a tardeada in Juárez. My father rushed back to the border, where my mother offered to return the money they had been saving together and reminded him that they were not comprometidos. Bertha had indeed gone with a girlfriend to a Sunday afternoon dance at the Cine Capri’s salon.Then and there my father abandoned his government job, officially proposed to my mother, and started making plans to acquire his green card and follow her to the United States. My father left Mexico because he loved my mother and feared losing her.

Rodolfo had also chafed against the practices in his government job as a cebollero, or onion-head, as they called the graduates of the Hermanos Escobar School of Agriculture. One friend had to buy a new truck for his boss if he wanted to ensure a government promotion. As my father would often tell me before he died of complications from diabetes, “Allá no te pagan por tu trabajo. Son puras movidas.” Over there they don’t pay for your work. It’s all trickery and corruption.

Rodolfo was soft in a way: a shy, smart man who only learned to love to dance because of my mother. He was macho with his children, but he tearfully revered his own mother, who had died when he was 10 years old. He constantly fought with Don Santiago and his new wife, Ofelia, the stepmother he despised. My father seemed stuck between his love for his homeland and his wish for it to be better. In the United States, he found an overly materialistic society that he often criticized for treating people like commodities. But he needed to leave Mexico to follow my mother, to get away from his father, and to fit better in a new place where corruption was not endemic. Like so many Mexicans before and after him, he wanted a new life.

My mother sits at the kitchen table next to a refrigerator covered with photos of her grandchildren. Nailed to one wall is a gigantic tapestry of the Last Supper, on top of which are tiny wooden facsimiles of the three missions of the Mission Trail. She has a familiar melancholy look: I know she feels she has not accomplished what she set out to do in this world. She tells me another story.

“Your father was very much a macho with me. In Ysleta, he allowed me to work, but only as an Avon lady. I wanted to work in a store. I had been a great saleswoman in Juárez at a shoe store before we were married. I had saved more money than he did. He also fought with you when you were a child, but at least he bought you many books. Your father wanted to create progress in his life, buy properties, but he was also stuck in the Old World. I did everything for him and helped him build this house. I even carted the buckets of cement as he stood on a ladder to pour the cement ring on top of these adobe walls around us. I loved your father, but he also used me.”

She’s mostly right, I think, even though she leaves a few details out in this memory riff. She almost always defended my father on all things. They were a united front. When my father’s projects yielded extra income, she was happy to use it to buy herself a new car and to travel around the world with him in retirement.

“I don’t know if you remember,” my mother recalls, “but one day Rudy and Oscar rushed into the kitchen from Sunday school at Mount Carmel with your father. The boys yelled, ‘Papá kicked Sergio out of the truck, and he ran away!’ Your father wanted you to work, and you refused him. You stood up to him. You wanted to study for school, and you refused to do another of his projects. I fought with your father. It was our most terrible fight. I told him, ‘If you don’t go after my son, if you don’t go get him, I will take all of my children and I will leave you. I don’t care. I can work, too, and make money. I’ll leave you.’ Your father called me some groserías. The worst words he has ever said to me. But he returned to the grounds of Mount Carmel. You were hiding inside the church.”

No one in the family ever confronted my father to his face until I did. We whined. We complained. But no one said, “No! I’m not doing that.” Until that day. I remember his apoplectic rage and embarrassment in front of my brothers. That weekend I refused to work. I was blessed as well as cursed with Doña Dolores’ willful character.

“I could only go to school to finish my GED until all of you were in high school,” she continues. “I lost so much time. I learned English, but I was always embarrassed by my accent. I also wanted to progress in Ysleta. But I took care of all of you and your father. La gente pobre sufre mucho y muchas veces nadien sabe. Poor people suffer a lot and most times no one knows. Now I am alone in my last days, surrounded by dust again.”

I think my mother has become more pessimistic with old age. One day, perhaps, I will also be as old as my mother is, and my body will also be a constant source of pain. I don’t tell her that her and my father’s work ethic made me tough. I don’t tell her that working together as a family created a bond of hard-won love that I tried to recreate with my own family thousands of miles away. I don’t tell her that my mission is to be a voice for this community because Ysleta embodies a very old spirit in America too often forgotten by insiders who take their place for granted. I don’t tell her that her stories—and those of my father, Doña Dolores, and Don José—were always the beginning of anything that mattered to me.

Mom, I know how much you did for all of us. In dusty, often forgotten Ysleta, you were the one who gave us hope.