She won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. President Kennedy praised her work. Vivien Leigh starred in her movie. Her life rivaled the character drama of Hemingway’s—four marriages, countless affairs, stints in New York and Paris and Mexico. But you may have never heard of Katherine Anne Porter. And even here in her home state, you’re even less likely to know that this 20th-century master of the short story could be the best writer ever born and raised in Texas.

For readers—and proud Texans—Porter’s local roots are worth tracing. To start, a look at the Katherine Anne Porter archives at Texas State University in San Marcos reveals her as a writer’s writer. Porter grew up nearby, in the rail stop of Kyle, and five boxes of papers related to her remain at The Wittliff Collections. Sit, as I do on a spring road trip, in the plush reading room, with its fresh-sawdust smell. Black-and-white photographs of her fellow Texas writers look over your shoulder as you page through letters from the likes of Ray Bradbury testifying to Porter’s greatness.

Bradbury called her a “steady and continuing influence in my life and work.” John Cheever proclaimed her a “lodestar.” The poet Rod McKuen wrote, “She is America.” More recently, novelist Alice McDermott has called Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider a masterwork, one she believes every library should stock and every American should read. Laura Bush has championed Porter, too—the first lady visited Kyle in 2002 for the dedication of Porter’s childhood home as a National Literary Landmark.

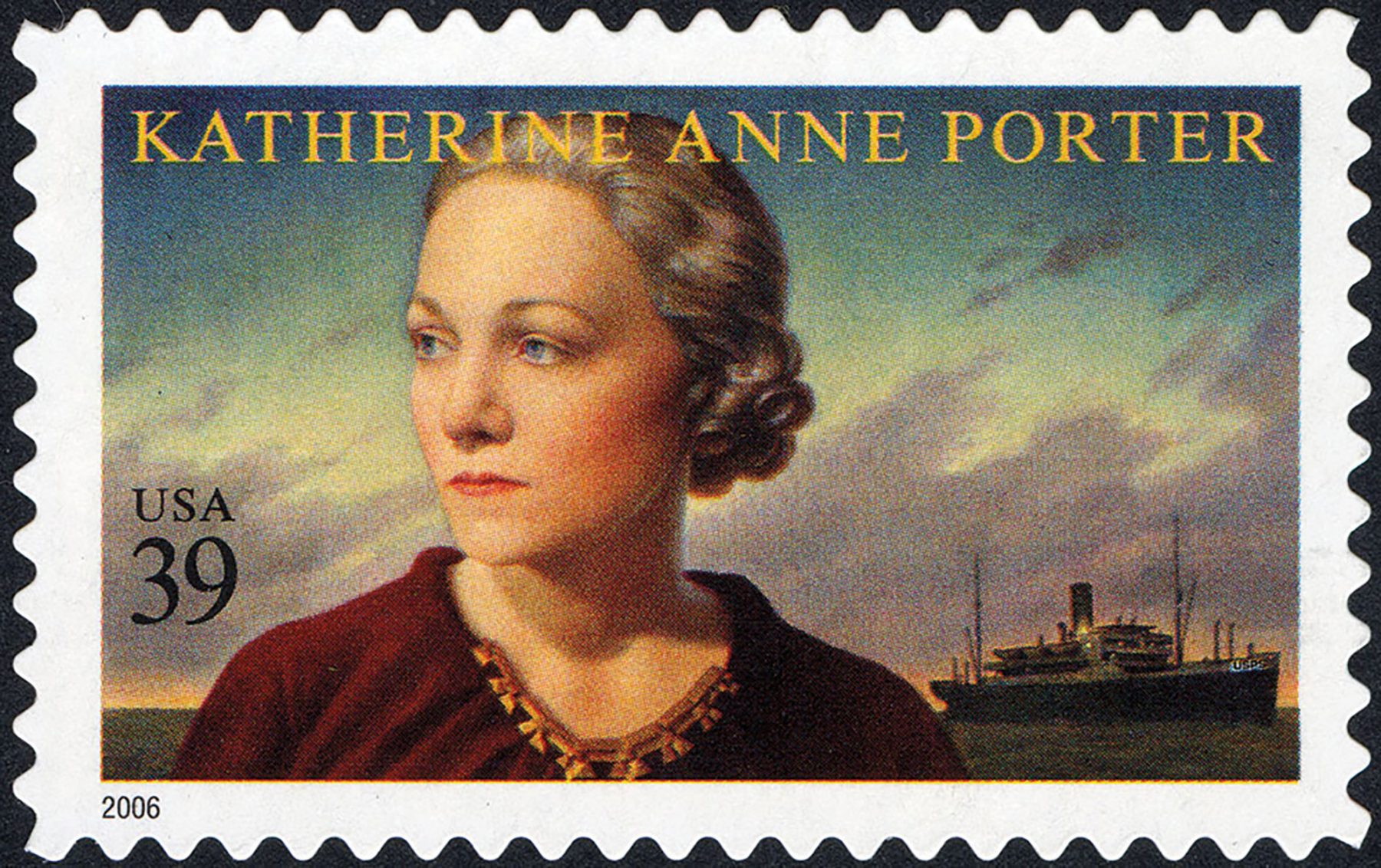

The Postal Service issued a Porter stamp in 2006.

Yet for complex reasons, Porter today isn’t always immediately connected with Texas. She painted herself as a glamorous daughter of the Old South, but in reality it was her hard-bitten upbringing in Texas that drove her literary and personal ambitions. She grew up female in a macho place—and felt conflicted about it, says Janis Stout, a Texas A&M professor emerita who lives in Brenham and has written two books about Porter, including South by Southwest: Katherine Anne Porter and the Burden of Texas History. “Her real roots were in Texas,” Stout says. “It shaped her mind. But she felt so marginalized and so limited here.”

Porter’s mother died when she was a toddler, and her father suggested that if she wanted to be a writer, she could write letters. Her brother once wrote to her: “As man is boss now will he be then. Finis.” And her first husband—a Texan whom she married at 16—abused her. Porter later wrote, in her story The Leaning Tower, of a character much like herself: “She was altogether too Western, too modern, something like the ‘new’ woman who was beginning to run wild, asking for the vote, leaving her home and going out in the world to earn her own living.”

Porter left the state at 28 and rarely returned. She worked for newspapers in Chicago and Denver, then lived all over the world at key 20th-century moments: Greenwich Village’s ’20s heyday, Mexico’s cultural revolution, Berlin’s World War II preparations. She tumbled in and out of love, and only briefly owned one house (on the East Coast). Some work channeled those cosmopolitan experiences, but her best writing often drew on her Texas childhood.

Porter’s life spanned 90 years—from 1890 to 1980—and she was born and buried (next to her mother) in the outpost of Indian Creek. It’s a still-unincorporated settlement in Brown County, 150 miles northwest of Austin. About an hour out of the capital city, subdivisions with names like “Rancho” and “Estancia” give way to actual ranches with family names on locked iron gates. The Hill Country flattens into the Edwards Plateau. Signs proclaim this area the “Meat Goat Capital of America.” The air carries a cedar tang, and prickly pear cacti spike the landscape. This is the kind of mostly tranquil, occasionally violent, ranchland Porter wrote of in stories like Noon Wine.

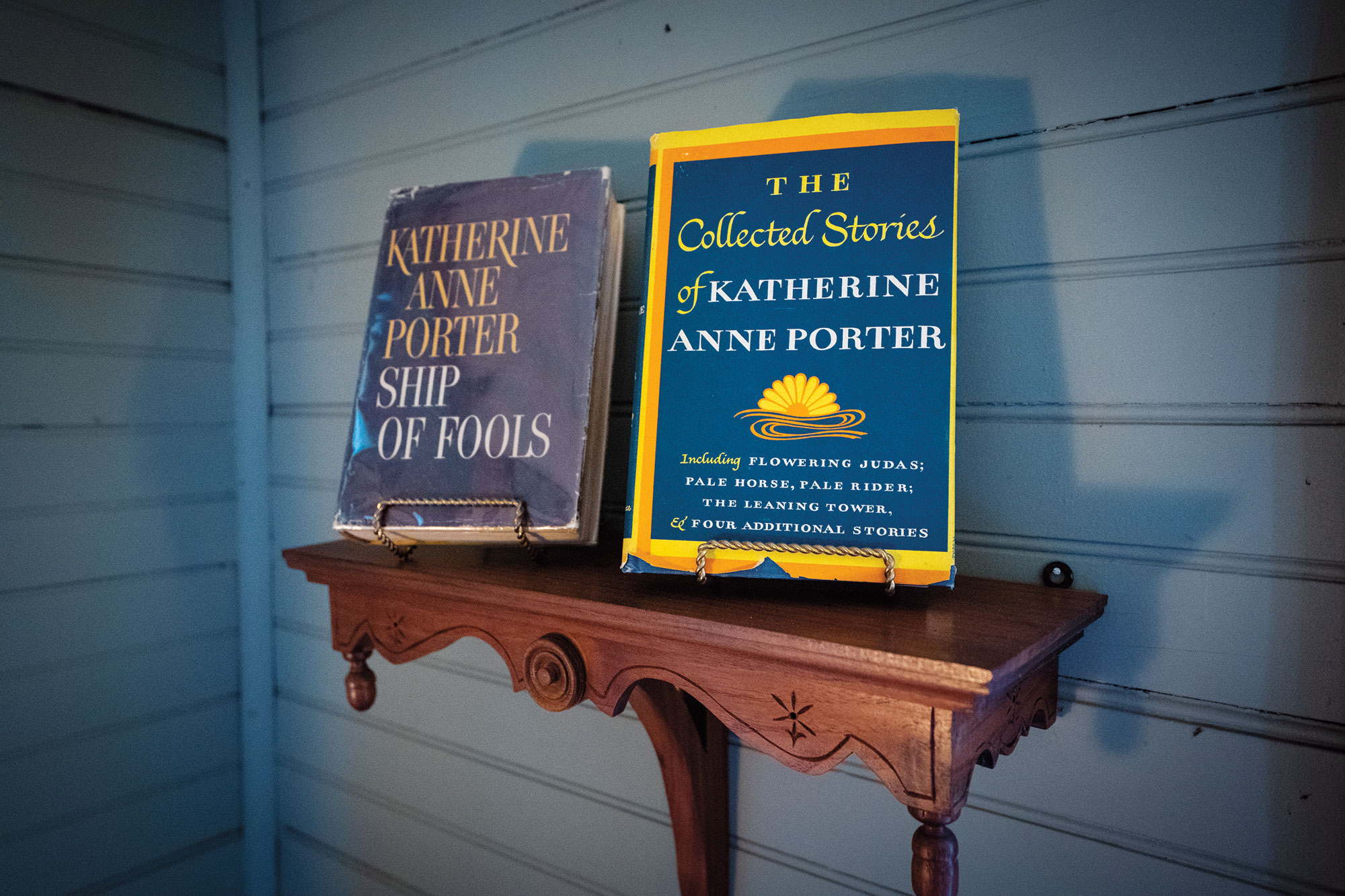

Porter’s works are on display in the literary center. Photo: Will van Overbeek

Outside Brownwood, the Brown County seat, a billboard promises cobblers at Underwood’s Cafeteria. A traveler may as well get directions to Indian Creek over lunch at Underwood’s, established in 1946. The aromas of yeasty rolls and buttery green beans compete with barbecue beef steak for airspace. Co-owner Leo Underwood says he’s not often asked about Porter’s resting place, but he’s willing to lead me out. Would it be like the Texas cemetery Porter described in her story The Grave? She wrote of “a pleasant small neglected garden of tangled rose bushes and ragged cedar trees and cypress, the simple flat stones rising out of uncropped sweet-smelling wild grass.”

Porter’s mother died when she was a toddler, and her father suggested that if she wanted to be a writer, she could write letters. Her brother once wrote to her: “As man is boss now will he be then. Finis.”

The only flowers at the Indian Creek cemetery set along County Road 237 turn out to be fake, brightening the grave of a local soldier who died in the Middle East. A few scrubby mesquites provide meager shade. There is no sign for Porter here. Luckily her tombstone sticks out as defiantly big among the rows. Yet it’s decorated only with blackened pennies. “She was not among the revered figures of Brown County history,” Underwood says. “Of course, Brown County wasn’t a literary mecca. But I feel sure I drank beer here. I feel sure of that.”

Indian Creek has a vacant air, but knock on a few doors and you might get an answer at a modern-day log cabin, where Leta Petzold appears in Navajo-print fleece. Her grandson read Porter in school, she says. If people here do know of their hometown girl done good, how come there is so little commemoration around her birthplace? A nondescript historical marker was erected in 1990 near her childhood home, but every plaque I spot on the route to Brown County notes only men’s names as the pioneer builders of sawmills and salt works. “We’ve been lax,” Petzold says of the comparative lack of Porter signage.

Porter was tiny when her mother died, and the family sent Porter and her siblings to live with their grandmother in Kyle, 30 miles south of Austin. Maybe 500 people lived in town then, according to Lila Knight, a local historian and board member of Hays County Historical Commision-Preservation Associates, the nonprofit that owns Porter’s childhood home. Kyle was founded as a rail stop between Austin and San Antonio, straddling the farmland of East Texas and the ranch lands of the West. A fictionalized Kyle became the setting for later stories in which Porter drew on childhood heartbreaks small and large, from shooting a rabbit (and finding stillborn babies in its reddened body) to her horror at the idea of lynchings.

“Her real roots were in Texas. It shaped her mind. But she felt so marginalized and so limited here.”

Old Kyle retains the scrappy feel of a frontier town, with shotgun houses on weedy lots, and streets like Rebel Drive and Cowboy Cove. Over the rise, though, the rooflines of endless beige homes poke up. This town is now one of Texas’

fastest-growing. The Railhouse bar and restaurant encapsulates the new Kyle; an old trackside feed store, it now features palm trees, sand volleyball, and a Lone Star flag across the galvanized-metal roof, all testifying to a vision of the Texas good life. Yet squad cars prowl, and neglected shacks look near collapse. There’s still a sense, as in Porter’s day, that the prosperity is fragile.

Once-quiet Center Street, where Porter’s childhood home remains, is now a busy highway. Her small house is a minty green with peach trim. The front and back porches (which Porter described generously as “galleries”) remain, along with an original “upping stone” for women to step into a carriage. Graceful pecans shade the place, which smells cozily of amber and myrrh from a candle inside. The house is home to a writer-in-residence. The current resident, Jeremy Garrett, gives tours on request.

Towns like Red Cloud, Nebraska, and Savannah, Georgia, play up their connections to their hometown writers—Willa Cather and Flannery O’Connor, respectively. In Kyle, the work is more subtle. “I don’t know that we make it our mission to go out and publicize Katherine Anne Porter,” Knight says. “It’s more supporting creative writing as a way to honor her memory.” Porter’s legacy, like the old Texas she grew up in, is tucked deep in the earth sometimes, but it endures.

A Porter Primer

A guide to some of the author’s greatest works

Noon Wine: Greek tragedy comes to the kind of Texas ranchlands where Porter grew up when a placid homestead becomes the setting of unexpected violence, and a family can’t withstand the consequences.

Pale Horse, Pale Rider: As a young reporter, Porter came so close to dying in a flu epidemic that the newspaper prepared her obituary. She drew on the experience in this dreamy masterwork that reflects on existential questions about love, war, and death.

The Jilting of Granny Weatherall: In what may be the Porter story most often assigned in schools, an old woman’s deathbed recollection of being stood up on her wedding day overshadows memories of the rest of her life.

Old Mortality: Porter conjures the wealthy, romanticized Old South she so often claimed as her heritage in this tale of family pain and the price of Southern womanhood. This is among the “Miranda” stories whose protagonist is thought to be based on Porter herself.

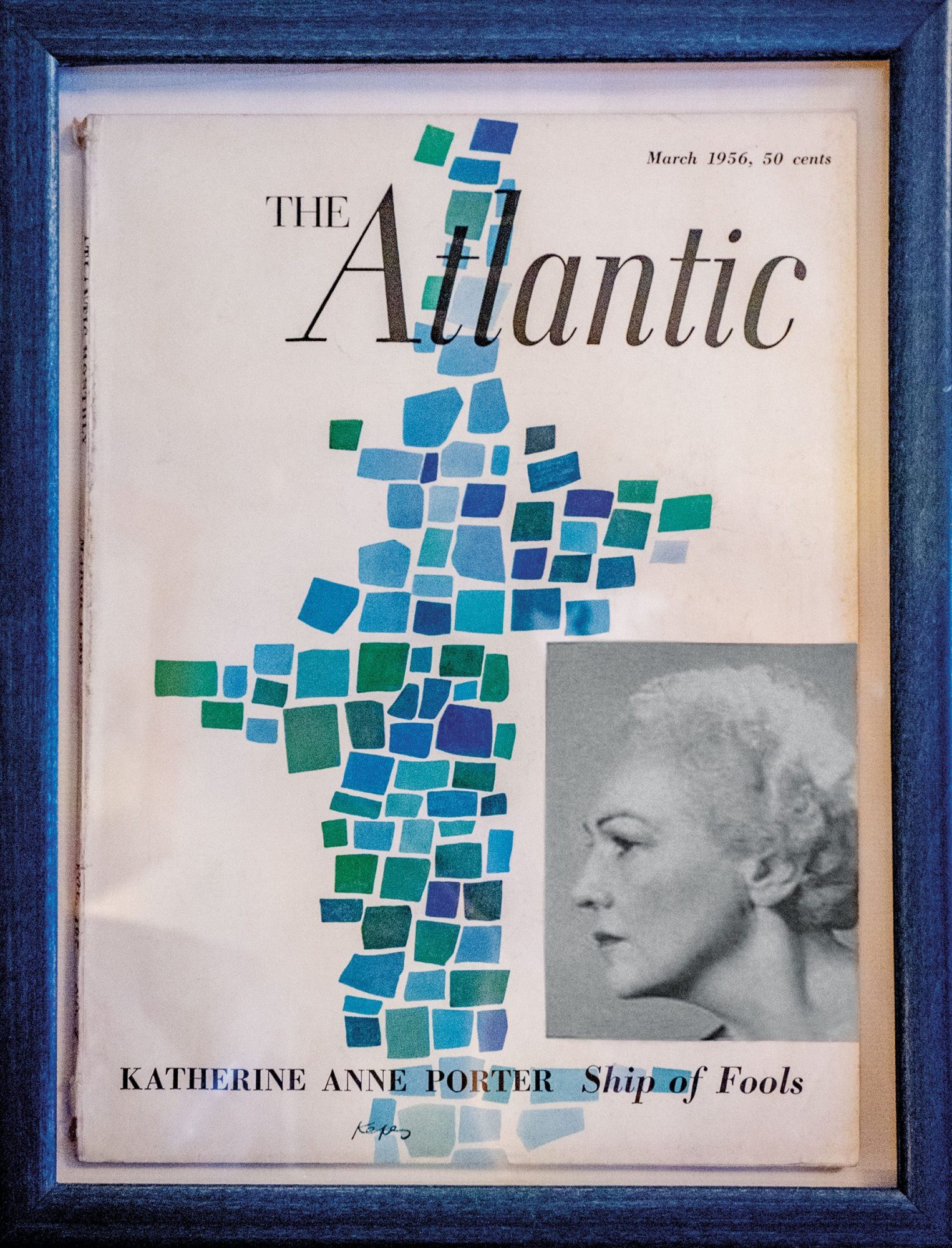

Ship of Fools: Porter’s single major novel was set on an ocean liner, not in Texas, but her abusive first husband appears in a Texan character on the ship. The book’s 1962 publication made Porter a rich literary celebrity, and a film version of the novel starred Vivien Leigh.