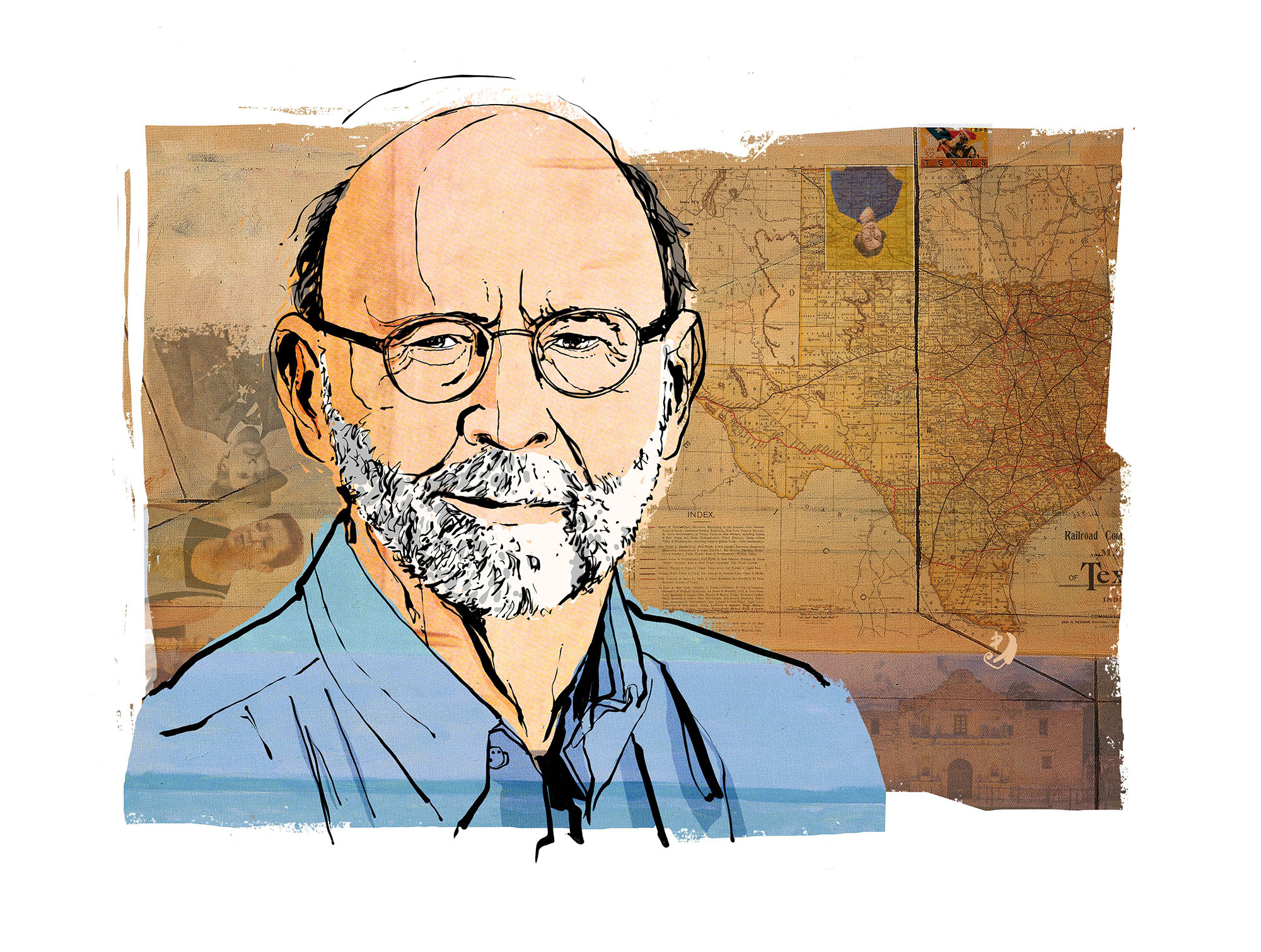

Stephen Harrigan has written about Texas for most of his life. He was born in Oklahoma and grew up in Abilene and Corpus Christi before moving to Austin, where he graduated from the University of Texas in 1970. He stuck around and started writing for Texas Monthly after it launched in 1973. Over his career, he’s written countless long-form articles about his home state, along with six novels (including the bestselling The Gates of The Alamo and more recently, A Friend of Mr. Lincoln), multiple screenplays, and five nonfiction books. It’s not surprising, then, that University of Texas Press tapped Harrigan to write an updated history of Texas. Six years later, in October, Harrigan released Big Wonderful Thing, a monumental work at 944 pages. The printer’s binding machine broke twice while running off the 35,000 copies of this massive tome. “It’s not a blueprint for what we should become or how we should change or what we should hold on to,” says Harrigan, 71. “It’s a story of how we got here.”

“You should always have a sense of place and where you are from. I want to make sure my grandchildren have that rootedness.”

Q: How did you begin writing Big Wonderful Thing?

A: I just plunged in because I knew if I hesitated or thought too much about it, I would lose my nerve. I had a general idea that I wanted to make this book conversational and not forbidding to a reader and not—for lack of a better phrase—too much like a history book. As I began writing, I began to realize I was trying to use the skills that I developed as a magazine writer and a novelist in order to make the people come alive and make the place come alive. To the degree that I had a strategy, that was it.

Q: Did you do a lot of research first?

A: I thought that I would spend a year doing research, but what I quickly found was as soon as I learned about something, I quickly forgot about it. I had to research each chapter and write it before I forgot what I had learned. Again, that’s the magazine writer in me: You become an instant expert on something, and then you become an instant idiot about it after

you’ve written.

Q: What was the most surprising thing that you learned?

A: I think the surprising thing for me as a writer was how much fun it was to write about people, particularly people who readers might not be aware of. For example, Emma Tenayuca, who was a great civil rights leader in San Antonio; or very sad people like Norma McCorvey, who was “Jane Roe” in Roe vs. Wade. It surprised me how human it was.

Q: In the narrative, you talk about “shadow” history. What exactly do you mean by this?

A: I knew going in that there were opportunities available to me, as a 21st-century writer, of understanding the mosaic of Texas history in a way that someone from a hundred years ago—an Anglo writer, like me—would not have thought to address. I’m not saying that I did a perfect job of making that story inclusive and diverse, but it was a priority. I just tried to cast my net as wide as possible in terms of all of the people who played a role in making Texas what it is.

Q: Was there an existing text of Texas history that you referred to as you were writing?

A: There were a number of books that I kept around more as a kind of timeline aid. I wanted to make my own decisions about who to write about and how to write about them. There are some sweeping histories of Texas, like Randolph Campbell’s Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State, and James Haley’s Passionate Nation: The Epic History of Texas. And, of course, Lone Star by T.R. Fehrenbach. I decided to avoid it because it’s an imposing book. I didn’t want his very intoxicating voice to infiltrate mine.

Q: What do you think is the most common misconception of Texas, and how do you hope to right it with this book?

A: I’m not on a crusade to tell people what Texas is or tell people what it should be because I don’t know those answers. I know what I’ve written, and I know what I’ve experienced. I do know that [Texans seem to want] a Texas identity—and it’s a very elastic identity. It used to be very specific. It used to be an Anglo identity, and it was a very chauvinistic and one-dimensional view of Texas. When you widen that lens to include everybody who made this state what it is, you realize that everyone has a stake in what it means to be a Texan. Nobody wants to cede that term to somebody else. It belongs to all of us.

Q: What are the intersections between writing nonfiction history and historical fiction?

A: In both of my historical novels set in Texas [The Gates of The Alamo and Remember Ben Clayton], there is a lot of serious research involved. My own feeling about historical fiction is that it ought to be reliable. A lot of the research for the novels that I’ve written about Texas fed into how I researched this book. The way of telling the stories is similar—the pitch varies; you begin in surprising places; you don’t begin a chapter where the reader might expect you to; you take detours to interesting people and places.

Q: How did you come up with the title Big Wonderful Thing?

A: Finding the right title is a real tricky thing. We wanted a title that was interesting and personal and a conversation starter. All the time that I was working on this book, I was really thinking hard about what to call it. I would read through Texas poetry and songbooks; everything had been used. At one point, I was ready to throw in the towel and call it Texas, but then I made up a list of possible titles and sent it to the publisher. One of them was from this Georgia O’Keeffe quote: “I couldn’t believe Texas was real… The same big wonderful thing that oceans and the highest mountains are.” I didn’t give much thought when I wrote it down. They all loved it. It was a controversial title among my writer friends. They genuinely wanted to talk me out of it because it felt trivial to them. It’s easy to say. It’s easy to remember. I like the idea that it’s a quote from Georgia O’Keeffe, who is a woman.

Q: As your Texan grandchildren grow older, what would you want them to know about the state of Texas?

A: It doesn’t matter where you are from: You should always have a sense of place and where you are from. I want to make sure my grandchildren have that rootedness. Whether they read this book or not, they will see it on the bookshelf, and they will realize their grandfather wrote this book about the place where they are from. They don’t quite yet understand all of the dynamics and implications of Texas history, but they’ll be taking Texas history in seventh grade, and they’ll learn about it—and I can fill in some of the gaps

for them.

Catch Stephen Harrigan on his book tour Dec. 5 at Wolfmueller’s Books in Kerrville and Dec. 6 at Front Street Books in Alpine.

bit.ly/BigWonderfulTour