A Sacred Refuge

The Comanche Medicine Mounds are a rare vestige of the mighty tribe that once controlled Texas

Ron Parker, great-grandson of Comanche Chief Quanah Parker; the Comanche Medicine Mounds

It’s not a long hike

to the top of the highest of the four Comanche Medicine Mounds, which are located a few miles southeast of Quanah, near the Red River in northern Texas. It’s also not easy. Even following a trail of switchbacks cut through the brush, I encounter obstacles: loose gravel here, horse crippler cactus there, not to mention the prospect of diamondback rattlesnakes lounging in the low shade of redberry cedars. But it’s worth the risk: When I reach the apex of the flat-capped hill, I feel like I’m walking on top of the world.

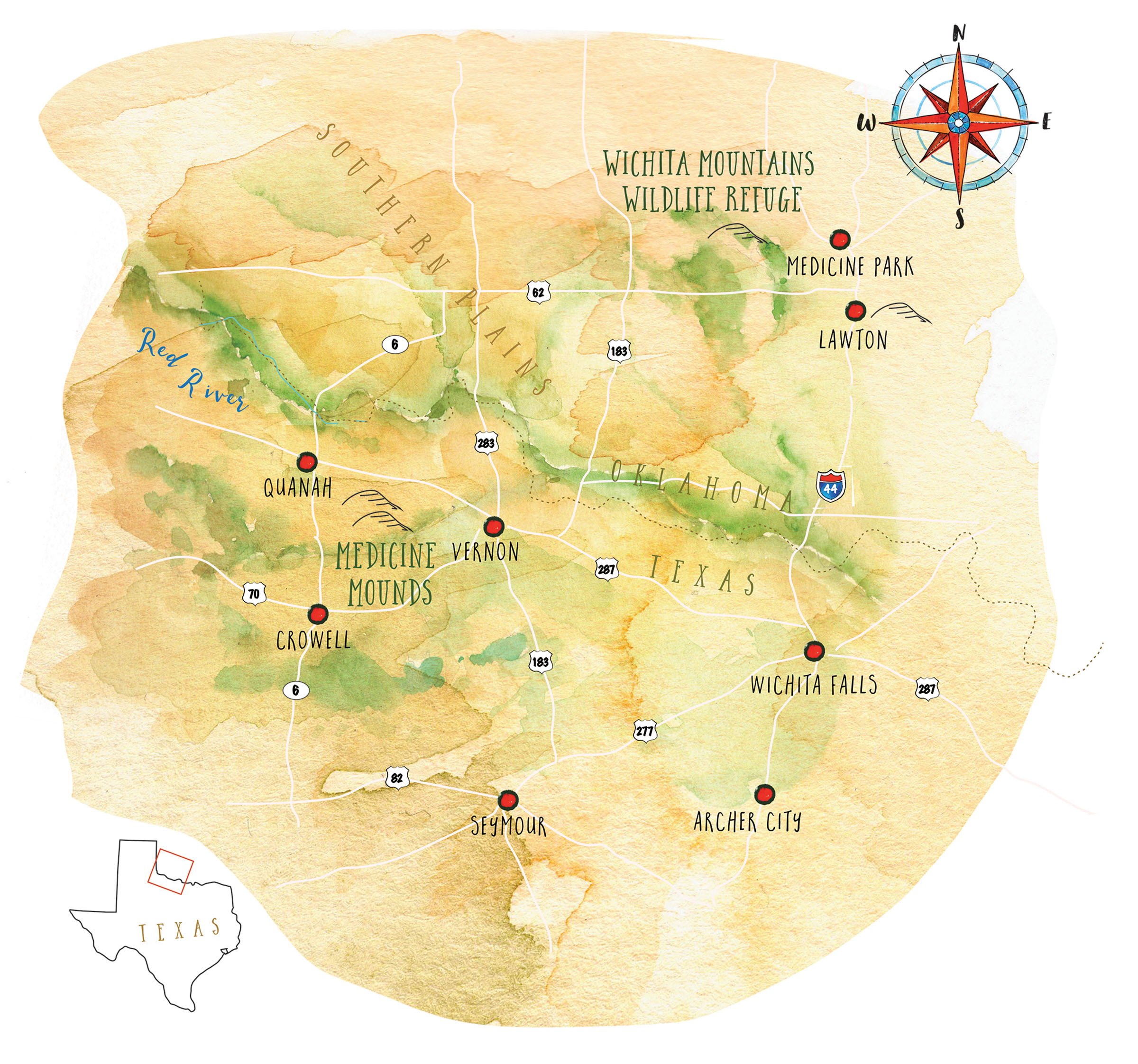

I’m actually only about 300 feet above the rolling plains that surround these dolomite mounds, but I can see for miles. The Wichita Mountains rise above the morning horizon 75 miles to the northeast in Oklahoma. Quanah Parker, the best-known Comanche chief, and his mother, Naduah (Cynthia Ann Parker), are buried at the Fort Sill Post Cemetery near the Wichitas. Since long before Quanah’s challenging tenure as a tribal leader in the late 19th century, and continuing to today, Comanche people have traveled to the Medicine Mounds in search of healing plants and spiritual renewal.

I feel the energy as I look out over the plains. My hike is part of the inaugural Quanah Parker Medicine Mounds Gathering, held last June in the town of Quanah and on the Medicine Mounds Ranch to celebrate Comanche heritage and Quanah’s legacy. The three-day public event—scheduled to return in June 2022—includes lectures on Comanche history and culture; demonstrations of Indigenous arts, dance, and music; and opportunities to participate in sweat lodges and hikes on the Big Mound.

During my hike, we stopped on the saddle connecting the two largest mounds for a cedar smoke and sage blessing conducted by Don Parker, Quanah’s great-grandson. Then we began climbing. Now, I’m at the top, feeling pure and at peace with myself and the world. Quanah also came here for spiritual quests, according to his family. “It’s a sacred place to us,” says Ron Parker, Don’s brother. “And it always will be.”

Numunu, “The People,” as the Comanche call themselves, left a distinct and compelling mark on North America. The tribe—“Comanche” is derived from a Ute term for “stranger” and was applied to the band by other native people—began as a small offshoot of the Shoshone in the 1600s and grew to become the most powerful military, political, and economic force between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Though no monuments to them are found at the Texas Capitol, they controlled most of what’s now Texas for decades during the 18th and 19th centuries.

At their peak around 1800, the Comanche numbered approximately 35,000. Then, hammered by drought, warfare, and smallpox and cholera epidemics, their numbers dwindled to as few as 1,500 by the 1870s. In recent years, the tribal population has grown. Now there are 17,000 enrolled tribal members, with 7,000 living on or close to the reservation in Oklahoma and the others scattered across the country, including 1,600 in Texas, according to the Comanche Nation. I had met the Parkers, who live in Lawton, Oklahoma, while writing about Comanche history, a saga that has interested me since my childhood in Oklahoma. So, when Ron Parker asked me to help organize the June gathering, I didn’t hesitate to say yes. It gave me a chance to climb the Medicine Mounds.

For years, the Medicine Mounds

piqued my curiosity as I drove US 287 between Wichita Falls and Amarillo. The four mounds begin roughly halfway between Chillicothe and Quanah and form a chain running northwest from the smallest, Little Mound, to the largest, the Medicine Mound, or Big Mound. The dolomite at their core is a sedimentary legacy from when Texas lay under an ocean millions of years ago. While the surrounding land has been cultivated over the last 150 years, the mounds have remained largely untouched.

“What you’re left with are the areas that couldn’t be modified,” says master naturalist Ben Sandifer, of Dallas. An accountant by profession, Sandifer has studied the Medicine Mounds extensively as part of his outdoor avocation. “The ground was too poor for farming, and it couldn’t support livestock grazing.”

The conical hills attracted American immigrants, who settled around them in the late 1800s. Remnants of a ghost town called Medicine Mound sit a short distance east of the Big Mound. Today the Downtown Medicine Mound Museum chronicles farm and ranch life near the mounds. Novelist Robert Flynn, an 89-year-old who was raised on a farm near Chillicothe, told me he picnicked with his family on top of the Big Mound when he was a kid during the 1930s, with thousands of acres of cotton and grain fields spreading below as far as the eye could see.

The rolling plains were a paradise for the Comanche, whose livelihoods centered around the American bison. Herds in this part of Texas numbered in the tens of thousands of animals and yielded tremendous harvests of hides and meat. But even for the Lords of the Plains, as Comanches came to be known, the grasslands could be harsh. Summers were brutal, and some of the rivers, such as the Pease, have a salinity that makes the water undrinkable to humans. The mounds provided respite with a spring at the base of the Big Mound. Cottonwood trees, whose bark could be fed to horses, grow nearby. In a 1995 article in the journal Plains Anthropologist, the late Comanche artist Leonard “Black Moon” Riddles told an archeological team studying the mounds: “Just as sure as anywhere there’s a Comanche, if there’s good water and there’s a knoll, they’d have been on top of that knoll.”

Comanche had other compelling reasons to visit. Serving as sky islands, the mounds harbor flora and fauna that have disappeared from the surrounding landscape—redberry cedar, pecan, hackberry, yucca, silver-leaf nightshade, and silvery wormwood among them, Sandifer says. “If you look at what the Comanche used in their faith and their healing practices, it was and is on the Big Mound,” he continues. “These are all critical pieces of Comanche healing. In some cases, you’d have to go 50 miles away to find these plants.”

Sanapia, born in 1895 on the Comanche reservation, was the last of the “eagle doctors”—tribal masters of herbal and spiritual healing. Before her death in 1984, she shared much of her knowledge with David E. Jones, an anthropologist whom she adopted as her son. In Jones’ 1984 book, Sanapia: Comanche Medicine Woman, the eagle doctor describes redberry cedar as a particularly important plant for both body and soul. Unlike red cedars and mountain cedars, redberries are relatively rare and noninvasive. “Only use that redberry kind,” Sanapia says. “It grows on those slick hills west of here,” meaning the Medicine Mounds.

During my visit to the Medicine Mounds, Don Parker harvests twigs from redberry cedars to use in his blessing on the saddle. Russell Neese, a former University of Oklahoma football player and an adopted member of the Parker family, has joined in our efforts. “Our spiritual beliefs are not hard to understand,” explains Neese, who speaks the Comanche language. “The golden eagle is sacred because it is the bird that flies the highest and is closest to God. Cedar smoke rises and makes its way to God.”

The land remembers Numunu, and The People recognize the land as a respected elder “and part of the creator’s handiwork,” Neese adds, encouraging us to be silent and take in what we see, hear, and feel. Warriors would climb the big mound after denying themselves food and water for several days and sit in meditation until they received visions. The Comanche also buried the bodies of esteemed tribal members here.

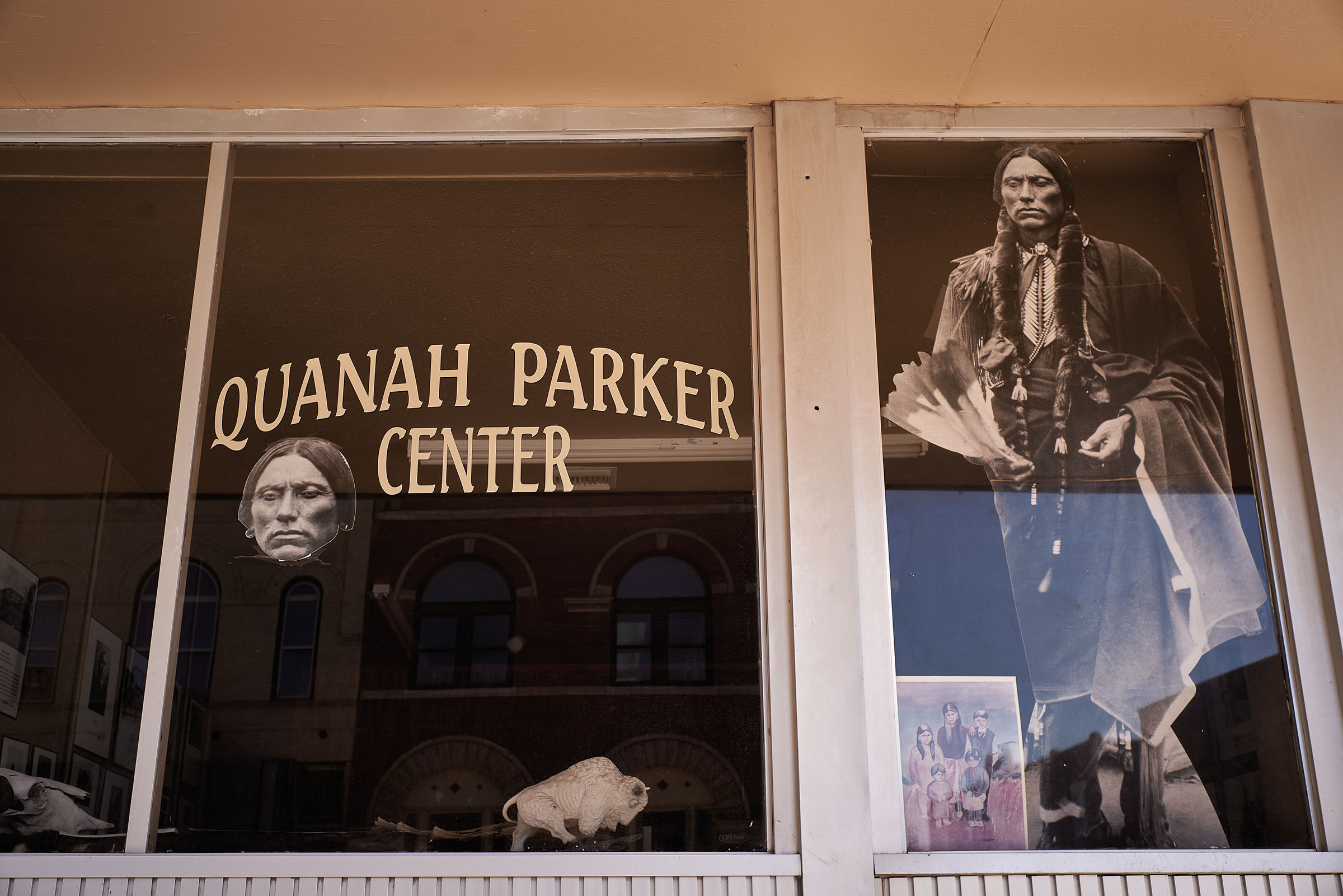

The Quanah Parker Society & Center in Quanah

As part of the Medicine Mounds gathering,

I participate in a symposium at Quanah High School, where I’ve been asked to speak on Comanche history. Much of what has been taught in classrooms, printed in bestselling books, and projected on cinema screens has been at best narrow and at worst incorrect.

“Foot troops were helpless against mounted Comanches in open country,” wrote famed Texas historian T.R. Fehrenbach in his 1974 book, Comanches: The History of a People, “and heavy cavalry could not match, meet, or break them.” It’s true, but also marginalizing. Comanche were much more than master horsemen. Spain, Mexico, and the Republic of Texas failed to subdue them. Recognizing the Comanche’s power, France opted to trade with the Comanche rather than fight. The Comanche were ferocious in combat, and at times they tortured enemies. But they were not “warlike, cruel, and treacherous,” as J.W. Wilbarger described them in his 1889 book, Indian Depredations in Texas.

In fact, the Comanche were a resourceful people whose greatest skills were innovation and diplomacy. They grew from a small Shoshone offshoot into an economic powerhouse with astonishing speed. They showed entrepreneurial acumen by creating an economy built on harvesting buffalo meat and hides. They traded with the French in Louisiana, the Spanish in what’s now New Mexico, and other Indigenous people, selling horses and mules to tribes as far away as the northern Great Plains and Missouri. They also engaged in human trafficking and peddled captives—some abducted, some captured in battle with other tribes—at the slave markets run by the Spanish in Taos and Santa Fe.

It’s hard to fathom the full extent of Comanche power as I look down at the plains from atop the Big Mound. It was a nomadic empire with no towns, cities, or fixed center. Numunu were divided into a dozen bands loosely associated with geographic regions. Everything was in continual motion for the Comanche. Standing where I am, I might have seen hundreds of men, women, and children and thousands of horses and mules on a given day in the early 1800s. Two weeks later, the prairie could be empty. The Comanche came and went that quickly.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Comanche trade machine was destroyed as drought, disease, and conflict with Western settlers and armies finally took their toll. Quanah Parker emerged as a military leader of the Kwahadi, or Antelope, band of the Comanche at the start of the Red River War in 1874. By his 20s, Quanah had already distinguished himself in battle. But the odds were against him as the U.S. Army launched a military campaign to force Indigenous tribes off the Southern Plains.

Relentless pressure, including defeats in the Texas Panhandle at Adobe Walls and Palo Duro Canyon, convinced Quanah to surrender to the U.S. Army and move the Kwahadi to a reservation established in the Wichita Mountains. On May 11, 1875, the Kwahadis began what’s come to be called the “Comanche trail of tears,” commencing at Teepee Creek, near the present-day town of Matador. By June 2, they reached Fort Sill, where the surrender was formalized. The Army confined the Comanche warriors to an unfinished icehouse building, where they were fed nothing but raw meat, much of it spoiled. Dozens of the detainees died.

In the face of such persecution, Quanah—whom the U.S. government designated the Comanche’s principal chief—tried to adapt to changing times and bring his people along. He negotiated deals with Texas cattlemen to lease thousands of acres of Comanche land in Oklahoma for grazing. He befriended people like Charles Goodnight and Theodore Roosevelt, and he’s thought to have been a behind-the-scenes advocate for the establishment of the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge, a lifeline at the time for the all-but-extinct bison. After white Texans named a town after him, he visited and gave it his blessing. When Quanah died in 1911, he was one of the best-known native leaders in America.

I know my 45-minute speech at Quanah High School

only scratches the surface. One of Quanah’s great accomplishments was preserving as much of his culture as he could. His friendship with Texas ranchers made it possible for Comanche to visit significant locations such as the Medicine Mounds after the tribe was confined to the Oklahoma reservation. Current Medicine Mounds Ranch owner Frank M. Bufkin III carries on that tradition. “Medicine Mounds Ranch continues to recognize the significance of the mounds and its ongoing relationship with the Comanche people,” says Jeffrey Bowles, who works in business development for the 22,000-acre operation.

Back on top of the Big Mound, a young Comanche man inserts an arrow festooned with feathers into the ground next to a redberry cedar. The arrow is a spirit stick, he tells us, in memory of his recently deceased father. He then offers up a brief prayer. I can think of no more fitting tribute than planting a spirit stick at this sacred place as the morning sun rises.

Comanche trail

Explore more history of the Comanches and Quanah Parker at sites surrounding the Comanche Medicine Mounds.

The Quanah Parker Society’s second annual Quanah Parker Medicine Mounds Gathering is set for early June 2022. Specific dates are pending. quanahparker.org

Named after Quanah Parker, the town of Quanah is a railroad and agricultural community and home to the Hardeman County Historical Museums. facebook.com/hardemancountymuseums

The Medicine Mounds Ranch offers guided tours of the mounds by appointment. medicinemoundsranch.com

In the ghost town of Medicine Mound, the Downtown Medicine Mound Museum chronicles local history. facebook.com/downtownmedicinemoundmuseum

In Canyon, the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum displays a Winchester Model 1873 rifle owned by Quanah Parker. The museum also owns the sites of two significant Red River War battles—Adobe Walls and Buffalo Wallow Fight. Find info at the museum. panhandleplains.org

About 50 miles north of Wichita Falls in Lawton, Oklahoma, the Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center displays tribal artifacts and can provide directions for visiting Quanah’s grave at Fort Sill and his Star House in nearby Cache. comanchenation.com/departments/comanche-national-museum-and-cultural-center