The wet Marshall heat slobbered my skin like an unwelcome dog’s tongue. I sat with my grandfather in the bare-walled living room of my grandparents’ senior living community, Oakwood House. My significant other, who’s now my wife, was outside making a phone call. Meanwhile, my grandmother slept away the afternoon in the bedroom. Her breathing was deep and loud for such a small woman—she was barely 5 feet tall in tennis shoes. I wondered if she still dreamed.

Dementia brings with it a darkness and terror so personal that the afflicted becomes a kind of prisoner in a cave—a faint, muddled echo of their former self. My grandmother was already an echo by then. Whenever I tried to start a conversation and she responded, “You sound like yourself,” I knew how gone she was because she no longer said my name. “Gordy,” which sounded like “Gawdy” in her southern Louisiana accent, had slipped from her mind. And Marshall, an East Texas home I idealized even if it wasn’t my own, was slipping from my life, too.

If people can become ghosts, so can places. I was trying to hold onto both as I sat in the living room while my grandfather made staccato conversation—“You doing good in Missouri? Teaching all right?” I wanted to preserve the moments and the spaces before all that forgetfulness and loss, and outside of the conflicts that families inevitably carry. It would take me years to understand how letting go was the only way forward, but for now I refused.

When my future wife returned from her phone call, my grandfather stood up. The stretched-out neck of his white T-shirt exposed his weight loss, and his nylon workout pants were two sizes too big. “Let’s you and I go to the house,” he said.

This was the summer of 2015. The house, which they still owned at the time, was off Arlington Road. Growing up near Dallas two-and-a-half hours away, I always thought the street sounded lofty, in a quasi-political way. As a kid, I associated it with Arlington National Cemetery, as if my maternal grandparents lived near the White House. Of course, they didn’t. But you learn family details as a child, and you craft associations from those details that fit the context of your relationships. Throughout my childhood, my grandparents were emotional, physical, and psychological icons. Official, regal, presidential. Naturally, their house had to carry the same weight.

My grandfather and I drove the 3.5 miles from Oakwood House. My grandparents had only recently moved into the senior living community, but heading up the long driveway and knowing the house was vacant, I already felt like a visitor.

The living room still looked the same: the plush furniture, the dark wood built-ins, the dustless order of books and framed photographs, the large wood-burning fireplace that would crackle daily during the semblance of winter Marshall offered. Loud voices and laughter had always floated through the living room during decades of extended family holidays, breathing flannel East Texas air. But it was quiet when my grandfather and I entered. Stiff and artificial, as if its intimate contents had been embalmed.

My grandfather and I took our seats in the adjoining recliners, a dim lamp turned on between us. The air conditioner whirred over our shared silence, and through the glass door leading to the covered concrete patio, the cicadas whined. When my grandfather finally spoke, his words fell heavy with anger and resentment.

Ever since they married in 1950, my grandmother had let my grandfather build a full half-life. He didn’t know how to cook, and he didn’t do laundry. His social calendar was a credit to her gregariousness and planning. When he retired in his 60s and consumed his days with golf, she learned to play so she could accompany him. Once he had a heart attack at age 55, my grandfather never expected to outlive my grandmother. Now here he was living a life that he too didn’t recognize.

My wife and I had been dating only a year, but we were already talking about marriage. I was thinking about how our notion of a shared partnership juxtaposed with my grandparents’. But as I sat in the living room hearing and feeling my grandfather’s anger, I didn’t judge. I was hurting—for both my grandparents and the loss of the life they had built together.

“I’m ready, Gordy,” my grandfather said. “I’m ready to go and for this to be over. It’s not fair.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

Outside, the big, green backyard was commencing its own echo. Rust covered the metal shed in the far corner, the plywood floor rotting and the ceiling caving in. English ivy overtook the flower bed, and the once-bursting bird feeders held not a single seed. I thought of the many visits across four decades. My parents had made it a point to truck my brother, sister, and me to Marshall as often as possible, where the close relationships I had built with my cousins and the steady routines of a smaller town translated to an intimate ease of living I never felt in Dallas. No matter what direction my life later took in adulthood—the stress of earning two graduate degrees in two states over five years and embarking on a family of my own—I could retreat to Marshall, regain my footing. In that moment, looking out at the wasting backyard, I wanted to believe this would be the case forever.

Marshall was always in my life, though not always in my grandparents’. My grandfather grew up in rural Mississippi and my grandmother in southern Louisiana. They relocated their family to Marshall from Baton Rouge in 1964, the summer before my mother entered eighth grade, so my grandfather could go into business with his brothers-in-law at the Timberland Saw Co.

Once they arrived in Marshall, they quickly put down roots. Roots deep enough that my grandmother was featured in a 1966 “Come Into My Kitchen” column in the Marshall News Messenger: “Vivacious Mrs. O.D. Smith confesses there are many things she enjoys more than cooking, but with a husband and four children who are all fond of eating, she dutifully does her best to please their palates.”

Roots so deep that as my own childhood experiences began to catalyze, Marshall became a part of my being.

My earliest memories, fragmented as they are, bear the scent of cinnamon and spaghetti sauce from the Christmases we spent there. During one Christmas Eve, my siblings and I crammed onto twin air mattresses in my grandparents’ formal living room alongside my seven cousins. Porcelain Precious Moments figurines smiled around us from walnut display cases while my grandfather told a story about Santa Claus flying over Texas. Then, with remarkable choreography, there was a thump on the roof, followed by footsteps scrambling toward the chimney. We children shouted with joy; my heart pounded. I didn’t sleep that night.

Much later, I learned that one of my uncles had climbed up on the roof to play Santa. How proud our parents were of that ruse.

Earlier that evening, we’d driven downtown to see the more than 1 million lights of the Wonderland of Lights Festival. We listened to the carolers and automated carol bells. We viewed the nativity scene, which I discovered during a Christmas trip two decades later was missing its baby Jesus. And we strolled past the brilliantly illuminated Harrison County Historical Courthouse with its Confederate soldier statue standing proudly in front of the east entrance.

That’s the paradox of my Marshall: The older I got, and the more I saw and understood of the world, the idyllic associations I harbored for it were slowly punctured. I began to realize the uncanny vacancies, the reality of loss, and the deeply conflicted history that saw a town leading racial or social progress in some ways while reasserting its entrenched Southern pride and prejudice in others.

Marshall sits comfortably as a nexus for the interlocking network of states that shares the dense shadows and deep faith of pine-logged country—Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana. The city was a leading supplier of munitions during the Civil War, a base for the Texas and Pacific Railway, and the home of the first Black college—Wiley College—west of the Mississippi River.

My grandfather told me these details, and my research confirms them. That’s how it would work. A history buff, he would mention a fact off-hand. I would ask a lot of questions, he would answer them, and I would leave Marshall and keep digging, seeing the city differently the next time I returned. Sometimes, those details added an admirable dimension, like when I learned about Wiley College. Other times, those details let the air out of the bucolic, small town bubble in which I’d forced Marshall.

About three years before my grandparents moved into Oakwood House, and soon after I had finished graduate school and taken a teaching job at the University of Missouri, my grandfather mentioned one such detail. In November 1863, Marshall became the seat of the Confederate government of the state of Missouri. Three years earlier, Claiborne Fox Jackson had been elected Missouri’s governor, while Thomas C. Reynolds, a secessionist, was lieutenant governor. Jackson’s mobilizing of a Confederate militia, in combination with a particularly bloody incident in St. Louis following the Union’s seizure of Camp Jackson, led to the occupation of Jefferson City by the Union army. Jackson and many state officials fled the capitol. A new state election was called, and Missouri’s Confederate government was born.

Exiled, the floating capitol of the Confederate government of the state of Missouri became something like a riverboat. It landed first in Arkansas. Then, 19 days before Christmas in 1862, Jackson died of cancer. Reynolds succeeded him as governor and, forced by the Confederate evacuation of Little Rock after the fall of Vicksburg, he set out for a new location.

Reynolds wound up sitting comfortably in a Victorian house, then a one-story, on Marshall’s East Crockett Street, with a wraparound front porch for him to stretch his morning legs. He designated the East Crockett Street house the new Missouri governor’s mansion. It stood across the street from 402 S. Bolivar St., the homely, unsuspecting capitol of the Confederate government of the state of Missouri—in Texas.

The stay didn’t last two years. But time gifted the historical oddity its own lore. A kind of siren song had sounded in Marshall, grown louder as the years passed and reverberated deeper as nostalgia—the potent anesthesia to progress—took hold. By the time the Bolivar Street capitol and the Crockett Street mansion were set to be demolished in 1950, a contingent of Marshall citizens weren’t having it.

“A famous East Texas Landmark, the Missouri Governor’s mansion of Civil War days, is slated for destruction,” wrote Robert M. Hayes in the Feb. 19, 1950, edition of the Dallas Morning News. “The picturesque 2-story frame structure … will be torn down within the next few weeks to make room for a lumberyard. … Early last year when reports were first circulated that the old mansion probably would be razed, Millard Cope, publisher of the Marshall News Messenger, launched a campaign to preserve the structure as a historic shrine.”

That happens with spaces and places. They become avatars for our identities. Both houses have long been demolished, but you can still feel the struggle over the city’s Confederate legacy.

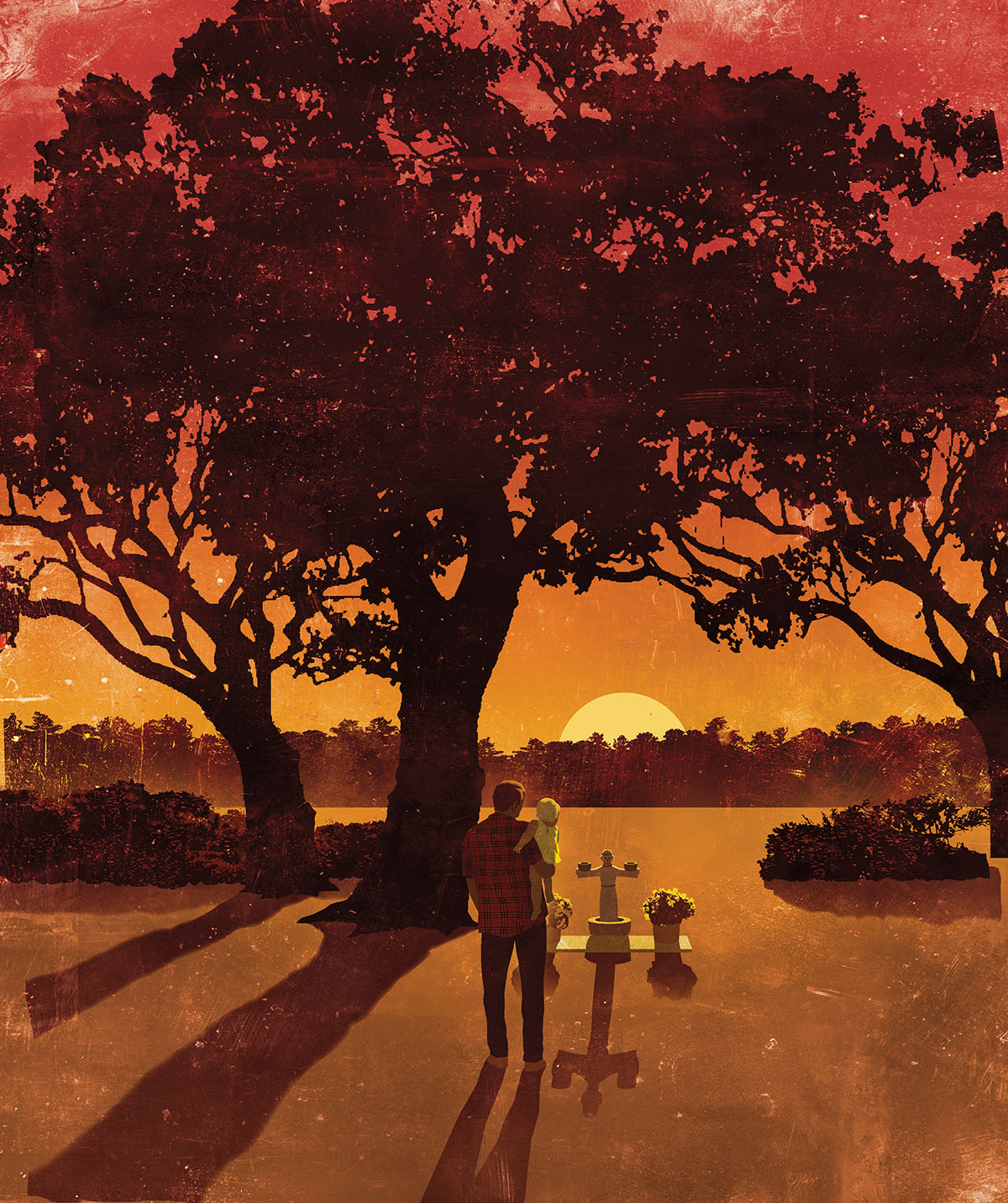

The summer of 2017, 14 days after my wife and I married in her home state of California, I stood in the interrogating sunshine of Marshall’s St. Joseph Catholic Cemetery. Surrounded by shrines, I watched my grandmother’s ashes being put into the earth. My grandparents couldn’t attend the wedding, but now here we all were. Afterward, our entire extended family got into our cars, drove past the congregation of pines tormenting the skyline and the 18-wheelers lumbering through town with piles of denuded tree trunks, and returned to the house with my grandfather to help and heal.

It was June 24.

My cousins and I tossed a football around in the backyard, sweating away the heat and humidity. My sister held her infant daughter, just weeks old. Then she handed her to my grandfather while she and my mother stood beside him on the back porch, all three adults smiling. I have the photo of this moment in my phone. Four months later I returned to Marshall to bury my grandfather, and when I look at that photo now, of four generations, I see the place that has been lost fading behind the people who must keep going.

My grandparents’ death has always been hard for me because of the outsized role they played in my life. But for a long time, I also mourned the collateral losses. Regardless of where different members of my extended family lived as years passed, we always came back to the house in Marshall, our North Star. One after the other, crossing like ships during our separate visits and mooring together when the timing aligned. No more.

I could hold on to Marshall’s echoes; I could capture those echoes to retell its stories. But Marshall’s echoes could only ever be echoes. The tighter I held onto them, the more they strangled my future.

I lost Marshall in the summer of 2017, but I had yet to let it go.

When I returned to Marshall this summer, five years to the day after my grandmother’s funeral, I was a father.

Holding my 13-month-old daughter, I stood at the edge of my grandparents’ plot in the perennial shade of a water oak tree. It was 94 degrees with 41% humidity, and we could hear the bells from St. Joseph Catholic Church almost a mile away. I held our daughter with my left arm, her sharp fingernails imprinting tiny moons on my triceps.

“That’s St. Francis,” I said, pointing to the concrete statue at the head of my grandparents’ granite marker.

My grandparents chose St. Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals, for their love of birds. St. Francis stood with his arms out, a bowl in each arm. In one of the bowls was a rock left by one of my uncles. The other was empty.

I asked my wife if we had anything to leave. She went back to our car and fished a seashell out of the glove compartment that she’d collected years ago at a California beach. She then sifted through the dash compartment.

“Oh look,” she said, then laughed. “And we have her umbilical cord.”

After our daughter was born and the nurse clamped her umbilical cord, we noticed one day it had fallen off in her car seat. I put it in the cup holder, then forgot about it. Seven months passed, and we decided to leave our decade-long life behind in Missouri and move to Denver. While packing up our house, I remembered the umbilical cord and had this idea to bury it behind the dogwood tree in our backyard as a token of our daughter’s first home. I searched in and around the cup holder and even under the floor mats but couldn’t find it. I thought it was lost.

“Seriously?” my wife said when I took both the seashell and umbilical cord and told her my plan.

“Of course,” I said.

The seashell I put in the empty cup of the St. Francis statue. The umbilical cord I buried at the edge of my grandparents’ marker.

After a bit, the three of us returned to the car and the air conditioning. I had finished buckling our daughter into her car seat when my wife held up her phone.

It dawned on us: It was the day of my grandmother’s funeral, the day we gave a piece of our daughter to Marshall, and the day the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

Of a different century and devoutly Catholic, my grandparents and I stood far apart on that issue, on many issues, regardless of how deep our love ran. And then there was our daughter, forced to now cross over into a world different from the one she was born into.

I traveled back to Marshall last summer expecting to experience longing and grief. Instead, listening to our daughter begin to fuss, I experienced something apart from that city and aside from that burden. Something like hope.

There’s this pervasive sense of looking back that I feel in Marshall. The unnamed Confederate soldier statue still standing outside the courthouse as cities from Richmond to Indianapolis to Houston remove or relocate their own similar symbols. The billboard at the intersection of US 80 and US 43/59 proclaims Marshall’s city slogan: “The Past Is Present.”

They’re all just echoes. As I listened to our daughter cry while we drove away from my grandparents’ grave, I realized I could let go. Let go of a past that isn’t a present. Let go of a place that’s no longer mine. My grandparents shared their lives and their home, showing me the many temperatures of love and the intention it takes to see love through. Now I can let go and carry that intention forward while I hold onto my future: my daughter learning to walk, her wobbly legs still gaining purchase, and inhabit the silence that allows her to speak.