★

Vaqueros pioneered the Texas ranching industry, but they've always stood in the shadows of history

By Katie Gutierrez

Photographs by Joel Salcido

Illustrations by Steven Noble

The Original Cowboys

Refugio “Cuco” Salas, a remudero, in 1971 by Bill Wittliff. Photo courtesy The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University.

A National Magazine Award finalist

Samuel Buentello was 14 years old

when he left the Rancho Nuevo in South Texas, the only home he’d ever known. In 1945, the road to nearby Hebbronville, a ranching hub 56 miles southeast of Laredo, wasn’t much more than dirt. All Buentello had was a paper sack of belongings and his mother’s tearful blessing. He had no money and no sense of what might come next, except work. Work was what he knew. Work was in his blood.

Buentello was a vaquero, a cattle worker whose horseback livestock-herding tradition was developed in Spain and perfected in Mexico before arriving in what would become South Texas in the 1700s. Vaqueros often lived with their families on the ranches they worked and were responsible for feeding, gathering, branding, castrating, and readying for market tens of thousands of cattle a year. Vaqueros were driving up to 20,000 head of cattle per year from Texas to Louisiana and Mississippi a century before Richard King of King Ranch began his legendary trail drives and the mythology of the American cowboy was born, according to historian Jim Hoy, who co-wrote the book Vaqueros, Cowboys, and Buckaroos with Lawrence Clayton and Jerald Underwood.

“The American cowboy, our great national folk hero, is recognized around the world as a symbol of our country,” Hoy says. “Cowboys as we know them, however, would never have come into existence without the vaquero. They were the original cowboys.”

Buentello learned every aspect of cattle work from his father, Pedro Buentello, who had learned from his own father in the hardscrabble late 1800s. A tall, imposing man, Pedro Buentello worked for various ranches and Rodeo Hall of Fame calf roper Juan Salinas before becoming a caporal, or foreman, at the Rancho Nuevo.

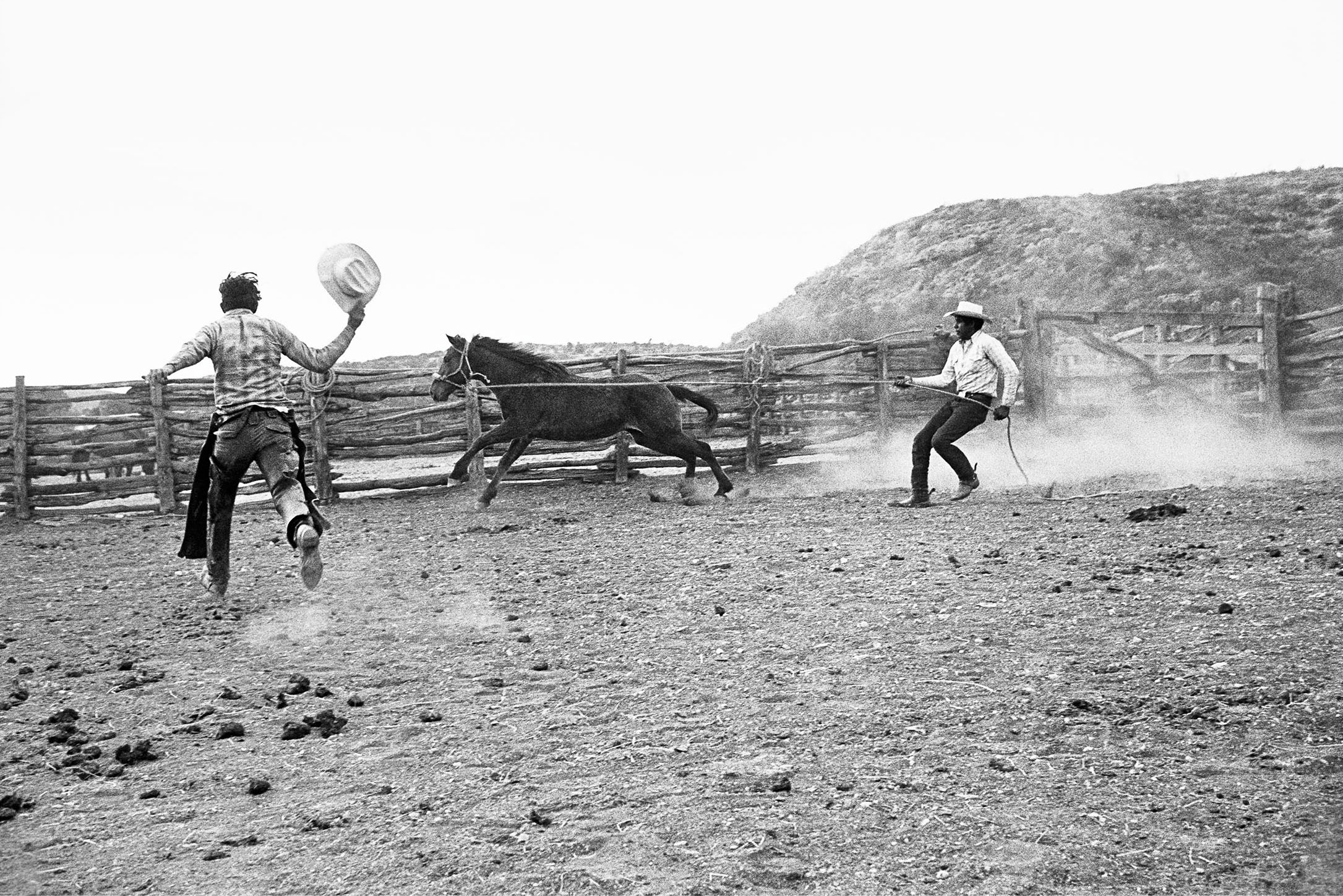

Pedro Buentello was a strict father and mentor. When Buentello was 9 and a powerful horse threw him in the corral, Pedro Buentello ordered, “Vengase—p’arriba.” Come here—get up. Buentello struggled off the dirt, mounting the horse again. For the second time, the horse lowered its head and arched its back, kicking its hind legs until Buentello flew off. “P’arriba,” his father commanded. The third time the horse bucked him, Buentello couldn’t get up. His pelvis was shattered, and he spent the next nine months in bed.

“Así fue el trabajo más antes,” Buentello says, reflecting on his childhood. That was the work back then.

In those days, a day in the life of a vaquero began early and often ended in pain. In this part of South Texas the Spanish once called El Desierto de los Muertos, or The Desert of the Dead, the summer heat is like a blowtorch, and the land, thick with mesquite and cactus, can rip a rider’s legs apart without the right protection. Yet if you ask any vaquero about his way of life—especially if he is old enough to remember rounding up cattle without the help of trucks or trailers or helicopters, without cell phones or GPS, when the men slept for months beneath saddle blankets underneath the stars—he’ll tell you he wouldn’t have it any other way.

The roots of the vaquero tradition are long and tangled within complex histories of colonialism. They extend from Northern Africa with the Muslim conquests in the mid-seventh century to the 16th century, when Hernán Cortés brought the first horses to what would become Mexico and Gregorio de Villalobos followed with the first cattle. To the Mayans, the mounted Spaniards were a terrifying sight: half man, half beast. After the conquests, the Spanish maintained their dominance by decreeing that any Native American caught riding a horse would be put to death.

But the livestock multiplied quickly and needed keepers. At first, Cortés and the conquistadores, who considered themselves above such labor, assigned the work to their Moorish slaves. According to Vaqueros, Cowboys, and Buckaroos, these enslaved Black Muslim men were the first true vaqueros—a term that translates to “cow men”—in North America. As the need for vaqueros grew, the Spanish law changed to allow Native Americans to ride horses, but only for work and only without saddles, which were the mark of gentlemen. Unwittingly, the Spanish ensured that Native Americans became superior horsemen.

By the 17th century, descendants of the Spanish and Native Americans (and, one can speculate, the Moors) were working cattle using Spanish methods. This was the first generation of Mexican vaqueros—men who had first ridden horses on cradles strapped to their mothers’ backs, learning as children how to snare small game using ropes made from native fibers such as maguey, lechuguilla, and horsehair. Later, they made lazos out of cowhide, a tedious process of drying the skins, cutting them into strings, and weaving a rope of six strands up to 60 feet.

They adopted sombreros for shade and leather chaparreras (later abbreviated as chaps) to protect their legs from thorny brush. They could throw la reata (later Anglicized as “lariat”) to catch the front feet or heels of an animal. They developed the technique called dar la vuelta (“dallying”) in which they wrapped the rope around the saddle horn instead of tying it off hard and fast. Both methods required immense skill to avoid getting dragged or maimed when roping wild cattle from the back of a horse galloping through the open frontier.

By the early 18th century, vaqueros were driving herds of cattle, horses, and sheep alongside Spanish missionaries to settle beyond the Rio Grande. But Texas—then still a part of Mexico—was harsh and unforgiving, marred by violence, heat, and drought. In the 1830s, to increase population, the Mexican government encouraged migration from the United States, setting the stage for Texas’ battle for independence and eventual annexation.

Enter Richard King and Mifflin Kenedy, friends and business partners who had served together in the U.S.-Mexico War and saw an opportunity in Texas’ herds of wild Longhorns, descended from the original Spanish breeds. Together and separately, they began to acquire huge swaths of South Texas acreage in the 1850s and ’60s, which would become the venerable King and Kenedy ranches, according to Voices from the Wild Horse Desert by Jane Clements Monday and Betty Bailey Colley.

At the time, though, King and Kenedy had no livestock experience. While Kenedy eventually hired vaqueros from the Rio Grande area, King traveled to Cruillas, Tamaulipas, in northern Mexico, offering the entire impoverished town housing and jobs for life if they would move back with him to his ranch. About 100 families accepted. Over time, they adopted the moniker of Kineños, or King’s men. (On the Kenedy Ranch, they were Kenedeños.)

The Mexican vaqueros taught King and Kenedy everything: how to work cattle and train horses, how to cull and keep the best stock, how to build a ranch. King and Kenedy trusted the vaqueros implicitly and took paternalistic responsibility for their well-being, and the vaqueros rewarded that trust with their loyalty. With his Kineños, King went on to drive tens of thousands of head of cattle to northern markets, helping establish the American ranching industry and building the most successful beef-producing operation in the U.S.

★

A.D. 711: The Moors, Black Muslim North Africans descended from the Arabs and Berbers, sweep into Spain on their swift desert horses—mesteños, later called mustangs—influencing Spanish horse culture and ruling much of the Iberian Peninsula for the next 800 years.

★

1492: Following the bloody Spanish Inquisition, during which 300,000 Moors were expelled from Spain, the last of the Moors are driven out, and the “Christian knights” of the Inquisition become conquistadores.

Even after breaking his pelvis at 9, Buentello loved riding and roping. By 14 he was a highly skilled vaquero. But after a falling out with one of the Rancho Nuevo’s patrones, Buentello left. He hitched a ride to Hebbronville, once ranked as the largest cattle-shipping area in the country, where he was let out on a corner in front of the Texas Theater. Across the street, a Bruni rancher named Floyd Billings was pumping gas into his big black car when he saw the boy. “Do you need money?” he called. No, Buentello said. He only needed work.

Billings drove Buentello 50 miles to King Ranch. By the mid-1940s, the ranch totaled 825,000 acres and more than 20,000 head of cattle. It had advanced methods of clearing brush, perfected the American quarter horse, and bred a line of thoroughbreds. King Ranch had become legendary, and the Kineños were the vaquero elite.

Two Kineños in crisp blue uniforms and cowboy hats greeted Buentello as the July sun beat down on his dusty khaki shirt and narrow-brimmed felt hat. The men looked at him skeptically. He was small and skinny for his age, more like a child than a man.

“A ver si pasas un test,” they said. Let’s see if you pass a test.

They took him to a corral, inspecting Buentello as he saddled and bridled a sleek dark stallion. “Ten cuidado,” they warned. Be careful. “He’s fast.” Buentello slipped his feet into the stirrups, knees high as he guided the horse to a trot, then a full gallop. “Suéltalo!” the men shouted. Let it go! Buentello loosened the reins while retaining complete control, land and sky blurring as the horse flew at full speed. The Kineños told him he’d start work in the morning.

Each day, Buentello rose when the sky was still pierced with stars. His job was to exercise 15 horses before noon. He didn’t realize it, but these were King Ranch’s thoroughbreds, including Assault. The horse would, the very next year, in 1946, become the seventh Triple Crown racing champion in U.S. history. To date, Assault is the only Texas-bred horse to accomplish this feat.

★

1519: Hernán Cortés lands on the western shores of what will become Mexico, introducing the first horses—mustangs—in this part of North America since their extinction there around 10,000 years earlier.

The best vaqueros have “cow sense,” the innate understanding of the way cattle think and move. They are masters of the lasso and ride as one with a horse. But one of the most important qualities of a good vaquero is the willingness to teach his skills.

In 1968, Samuel Torres Sr. was a caporal at Alta Vista, the headquarters of the original Jones family ranches that once spanned more than 300,000 acres between the Rio Grande and the Nueces River. His sons, Samuel Torres Jr. (Sammy) and Gerardo Torres (Jerry), lived for the days he would take them to roundups. They’d pick out their clothes and put their spurs on their boots, and by 3 a.m. they’d be heading to the camp house a mile or two from the main ranch. The cook had coffee going, plus beans, pan de campo, and tortillas. While they ate, they could hear the distant thundering of horses. The remuda was coming in, up to 300 horses being brought from the pasture by two remuderos, brothers Felipe and Miguel Piñon. By 5:30, the men—and boys—were saddling up.

On most large ranches, roundups happened twice a year, once in the spring to brand, vaccinate, and castrate calves and colts; and once in the fall to cull cattle for market. Torres Sr. was a patient teacher, not just to his sons but to other young vaqueros, including Jose “Red” García Jr. García was used to learning on the job. The first time he castrated a horse, a vaquero had told him, “You’ve seen enough—now do it.” But Torres Sr. took 18-year-old García under his wing, explaining which two vaqueros to keep in sight and which landmarks to look out for to maintain his position when driving cattle.

Marty Alegria, who was born on King Ranch in 1966, also benefited from mentorship by legendary vaqueros. Chief among them were Kineños Alberto “Lolo” Treviño, whose ancestry goes back to the de la Garza family who owned the land before King purchased it; and Martín Mendietta, a fifth-generation Kineño and caporal. Alegria grew up in a Kineño colony of about 100 brick houses and spent weekends and school holidays alongside old vaqueros who would teach the children how to rope, ride, and break horses as well as how to read cows and people. Eventually, Alegria graduated to working big corridas with 30 other vaqueros, gathering thousands of head of cattle on pastures up to 10,000 acres.

The best thing Alegria learned in his 41-year career at King Ranch, he says, is how to palpate cattle to check for pregnancy and ensure high-percentage calf crops each year. With intricate knowledge of the cow’s reproductive system, Alegria can tell whether the animal is pregnant as early as 35 days after conception, when the embryo is only 9 to 10 millimeters long. Over the course of his career, he has palpated upwards of 280,000 head of cattle. Alegria’s eagerness to pass his knowledge on to fellow vaqueros is how he measures his success. “I ain’t gonna take this to my grave,” he says.

★

1521: Gregorio de Villalobos brings cattle, which will crossbreed to become the Texas Longhorn, from the West Indies to Mexico. As the cattle and horses multiply, a workforce of commoners, or paisanos, becomes necessary. The first vaquero in North America is thought to be Hernán Cortés’ Moorish slave, followed by Native Americans who learned to ride without saddles.

Any conversation about the legacy of Texas vaqueros must contend with difficult truths. The first is vaqueros’ general erasure from cowboy mythology. In her introduction to Voices from the Wild Horse Desert, Ana Carolina Castillo Crimm notes that a history of King Ranch published in the Corpus Christi Caller-Times in 1953, which describes the lives of the Anglo foremen in detail, neglects to mention the Kineños at all.

This isn’t a coincidence. The Mexican Revolution, between 1910 and 1919, led to a spell of deadly anti-Mexican sentiment. The border became militarized, and the Texas Rangers grew from a small militia group to an official law enforcement agency that targeted “…both the ‘Indian warrior’ and the Mexican vaquero as enemies of white supremacy,” historian Monica Muñoz Martinez writes in her book The Injustice Never Leaves You. National political cartoons portrayed Mexicans as revolutionaries and bandits, and this is how they came to be depicted in most Western literature and film, opposite the noble white American cowboy. Notable exceptions are the 1972 photo book Vaquero: Genesis of the Texas Cowboy by Bill Wittliff, founder of the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University; and the 1958 book With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero by the Texas folklorist Américo Paredes.

“Mexican vaqueros have largely been erased from Texas popular memory because they provide a picture of a Mexican that contrasts with racist depictions of them as unskilled, uneducated, dangerous, and a threat,” Muñoz Martinez says. “To tell the history of the vaquero you also have to tell the history of a long effort to displace Mexicans from economic, cultural, and political power in South Texas.”

Sammy Torres Jr. at his home in Hebbronville, with a photograph of his father, Samuel Torres Sr.

To Muñoz Martinez’s point, vaqueros have never been paid commensurate with their skill or the importance of their contributions to the cattle industry. “It’s not going to make you rich,” Alegria says. Indeed, in the 1940s, Pedro Buentello made $25 a month, one-eighth the median U.S. income. In the 1970s, García made $175 per month, one-fifth the median U.S. income, per the U.S. Census Bureau. The most Buentello ever made was $1,200 a month in the 1980s. Until recently, there was no pension or retirement plan for vaqueros. They simply worked until the work changed. At King Ranch, when a vaquero got too old to ride horses, he would inspect fences or fill water barrels, chop wood or teach the children, like Alegria, and pass the tradition forward. Stories abound about vaqueros whose hearts gave out the day they could no longer work, as if broken by the loss of life on the range.

The model of lifelong work on a ranch began to change in the mid-1970s when helicopters started being used for roundups. Pilots were paired with old vaqueros and, without headphones to communicate, would rely on their body language for clues: If the vaquero winced or turned, the helicopter was getting too close or pushing too hard. Once the pilots learned how to herd cattle from the sky, they became known as helicopter cowboys. For $200 to $350 an hour, a helicopter might take half a day to gather a pasture that would take 30 vaqueros two days.

Mechanizing any process takes a human toll. Helicopters were one reason King Ranch eventually laid off or offered early retirement to more than half of its Kineños in the 1970s and ’80s. Many of them had been born there and expected to die there. Across Texas, as helicopters, trucks, and trailers became the norm and younger men were drawn to an education or better pay in the oil fields, the number of vaqueros dwindled.

Today, ranches that once employed two dozen or so vaqueros might only have a half dozen. Knowledge of the old ways is disappearing along with them. Torres Jr. has tried to remedy that by founding the Vaqueros of South Texas, a Facebook group 9,000 members strong that posts pictures and stories of vaqueros who have long since passed. “My dad’s skills never diminished,” Torres Jr. says, “but his skills were no longer needed. There were very few ranchers who might have come and pat him on the back and said he did a good job. So, I figured now’s a good time to recognize vaqueros for all the work they did and still do.”

★

Late 1690s-early 1700s:

Mexican vaqueros—typically mestizo, or descended from Spaniards and Native Americans—drive herds of cattle and horses alongside Spanish missionaries and soldiers, establishing the first missions and ranches north of the Rio Grande.

South Texas is usually sepia-tone and sunburned, but on the May day I visit Santa Fe Ranch, just north of Linn near Edinburg, everything is luxuriantly green after a recent rainfall. Scarlet-throated wild turkeys strut around, and cream- and tan-colored Charolais cattle graze the pasture alongside the mile of road leading to Mike East’s home.

The East family is descended from the Kings, and Santa Fe Ranch used to be a part of King Ranch. East’s story begins with Moto Alegria, the accomplished vaquero (and Marty Alegria’s great-great-uncle) who helped raise two generations of East children. Moto Alegria was a constant, protective presence who intervened if East’s mother went to spank them. Once, Moto Alegria rigged up a harness for a tortoise out of a string and tied an empty shoebox for it to pull, a playful memory East treasures.

Black and white photos of vaqueros line East’s hallway. There is Tiburcio Rodriguez, standing beside East’s grandfather, father, aunt, and uncle, who crouch with their arms around dogs. Many years later, as an old man, Rodriguez still rode horseback to check on fences and windmills every day. East’s grandmother would pour tequila into a cup and tell East, “Take this out to Tiburcio.”

There is also Juan Molina, dust kicking up from his boots as he helps a young East and his father rope a horse they’re about to castrate. And there, in a place of honor on the mantel, sits a plaque of gratitude from the family of Paublino “Polín” Silguero, who insisted on working until he took a fall in his 90s. Years later, when East visited him in the nursing home, Silguero’s first question was how many vaqueros East still employed. (That answer, today, is seven.)

East tells me about Buentello—the boy who left home at 14 with only his shopping bag of belongings. After exercising King Ranch thoroughbreds for several years, Buentello worked for East’s father before going on to train Arabian horses in Corpus Christi and eventually managing a ranch in the Rio Grande Valley. Now, at 90, Buentello might be the oldest living vaquero in South Texas.

When Buentello arrives for lunch, he is wearing a black plaid shirt, tooled leather belt, and jeans with a crisp iron crease. It’s been more than 65 years since Buentello worked for East’s father, but the warmth between the men transcends time.

“You were kicking rocks because you didn’t want to go to school,” Buentello tells East in Spanish, reminiscing about the year they met. “And Motito would tell you, ‘You have to go to school, Mikey.’”

East smiles at the mention of Moto Alegria. “I wanted to be with the vaqueros,” he says.

For the next two hours, Buentello and East talk about their tough upbringings and the men they knew—their escapades and heroics and deaths. Buentello’s daughter, Magda Buentello-Vergara, has hired a videographer for the occasion. Buentello is the last of an age, and after all, it’s always been up to vaqueros to pass down their own tales.

In a space between stories, Buentello reflects silently. “El tiempo se pasa,” he says. The time passes.

★

1854: After purchasing the 15,500-acre Rincón de Santa Gertrudis land grant and establishing King Ranch, steamboat captain Richard King travels to Cruillas, Mexico, and offers the expert vaqueros there housing, food, and jobs for life if they’ll return with him to King Ranch. The vaqueros become known as Kineños, or King’s men, and the Texas ranching industry is built with their labor.

The Vaquero Experience

Sites across the state offer opportunities to learn more about the vaquero way of life.

AUSTIN

The Texas history galleries at the Bullock Texas State History Museum include Tejano ranching artifacts, cattle stories, and more. thestoryoftexas.com

HEBBRONVILLE

In November, Hebbronville—designated the “Vaquero Capital of Texas” by the state Legislature—holds the annual Hebbronville Vaquero Festival. facebook.com/vaquerofestival

Alta Vista Ranch, one of the original Jones family ranches, offers day trips and lodging. jones-altavistaranch.com

SAN ANTONIO

The Briscoe Western Art Museum showcases artifacts and sculptures representing the vaquero tradition and will host the exhibit Vaqueros de la Cruz del Diablo, which offers a look at the lives of norteño cowboys from Sonora, Mexico, through the lens of photographer Werner Segarra, beginning September 23rd. briscoemuseum.org

The annual San Antonio Stock Show and Rodeo in February presents an event entitled Noche Del Vaquero.

sarodeo.com