“There’s no shortage of rattlesnakes in Bosque County,” says Taylor Sheridan, co-creator of Yellowstone, the highest-rated cable TV show of 2020. “I don’t know how I never got bit. Now I’ve gotta find wood to knock on because we’ve got a scene with some rattlesnakes tomorrow.”

Yellowstone is set on a Montana ranch that’s “the size of Rhode Island,” according to the show’s ruthless patriarch, John Dutton, played by Kevin Costner. But the roots of the gripping contemporary Western can be traced to a 214-acre ranch near the town of Cranfills Gap, 54 miles west of Waco. That’s where Sheridan, who writes and directs the series, learned to ride horses, shoot guns, and make movies in his head. He named his production company Bosque Ranch to honor where he comes from.

“I’m deeply influenced by where I grew up and how I grew up,” says Sheridan, speaking by phone from the set in Montana. In addition to Yellowstone, Sheridan is also responsible for the creation of the “neo-Western” film trilogy of Sicario (2015), Hell or High Water (2016), and Wind River (2017), a run that led Esquire to declare him “our generation’s greatest Western storyteller” in 2018.

“We didn’t depend on our ranch for income,” says Sheridan, whose father was a cardiologist in Fort Worth. “But it’s where I learned how to become a cowboy.” Sheridan’s first job, at 14, was working on a cattle ranch a few miles outside of Cranfills Gap for $400 a month and a bunk.

His mother, Susan Drew, grew up in Waco, and her sanctuary was her grandparents’ ranch near the Bosqueville neighborhood. She wanted her children to similarly “have an opportunity to learn firsthand about the peaceful feeling of freedom in nature,” she says. The family bought the Cranfills Gap ranch in 1978, when Sheridan was 8. They would drive the 85 miles south from Fort Worth for weekends, holidays, and summers.

“Back then, the Gap had a hardware store, a grocery store, a feed store, and a fillin’ station,” Sheridan recalls. “And that’s about it. We were pretty isolated on the ranch. We’d get excited when the propane man would come to fill the tank.”

“We were pretty isolated on the ranch. We’d get excited when the propane man would come to fill the tank.”

The family spread was part of a Norwegian settlement comprising the family’s 1870 stone house, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and 14 other 19th-century homes built on a ridge above “Little Norway,” the Gap, and the surrounding area. The ranch is a couple miles up a dirt road from the area’s most popular tourist attraction, St. Olaf’s Kirke, better known as “The Rock Church” for its intricate stone masonry. Built by Norwegian immigrants in 1886, the landmark was beautifully restored in 2010 and is open to the public.

The church was a place of mischief for Sheridan when he was about 12 or 13. “Me and a couple friends liked to sneak upstairs to the organ and wait for visitors. When someone came in, I’d wait a minute and then play a really dramatic chord,” he says, laughing at the memory of tourists running out of the “haunted” church. When told there’s now a locked gate protecting the organ, Sheridan says, “That’s probably because of us.”

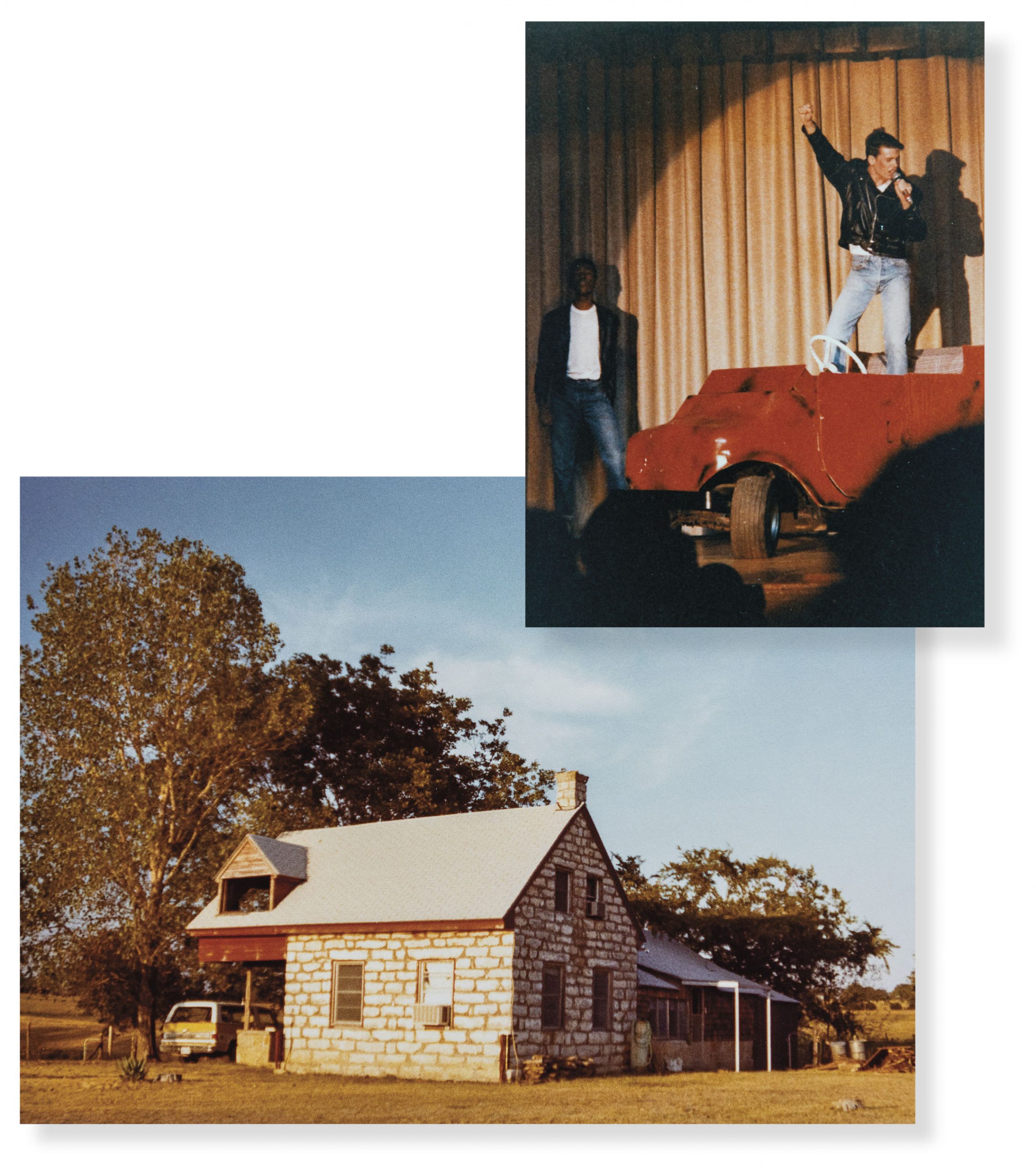

Taylor Sheridan in Grease; the family ranch. Photos courtesy Susan Drew.

Multiple Native American tribes predated the Norwegians in the Gap, and the 1970 discovery of a Paleoindian burial site in Bosque County made the area a focus for archeologists. “We always had folks from the University of Texas digging around on the ranch,” says Sheridan, who found not only Native American arrowheads and tools, but also a loaded 1800s pistol. The artifacts fueled Taylor’s imagination, as did local lore.

In 1867, Comanches in the historic upper settlement of the Gap kidnapped 14-year-old Ole Nystel and held him for three months. “We all knew that story,” says Sheridan, whose interest in Native Americans is found in several of his screenplays, especially his directorial debut, Wind River, a crime story set on a reservation in Wyoming.

The Viking Theater on Third Street hasn’t shown a movie in more than a half-century, but the Norwegian influence is still felt in the Gap (pop. 281). The old weighing station for wool and mohair is still where it was in the 1970s when the fields were full of angora goats, but today the scale is a display piece inside the Horny Toad Bar and Grill, a former feed store. The place is famous for its chicken quesadillas, not lutefisk and boiled potatoes, the traditional dish served at the Cranfills Gap school cafeteria on the first Saturday of December, in conjunction with Bosque County’s “Norwegian Country Christmas.”

During his high school years, in the late ’80s, Sheridan lived a dual identity that would merge in his adult life. He was that rare weekend wrangler who was also a theater kid, playing Kenickie in Grease at Paschal High in Fort Worth. At 16, he auditioned for Piaf, with Cowtown’s well-regarded Stage West Theatre, and got a part. “The play was held over, and I had to miss a school dance,” he says. “But I was getting paid to act.”

When the weather’s nice, the Horny Toad Bar and Grill in Cranfills Gap is a favorite stop for motorcycle enthusiasts. On a Saturday in late September, Third Street was so full of bikers, the Sheridan credit that came to mind was Sons of Anarchy. In 2008, Sheridan landed his first big acting role in Hollywood playing the no-nonsense deputy police chief in the hit series about an outlaw motorcycle gang. But when he asked for a raise after two seasons, the writers killed him off.

It wasn’t long, however, before Sheridan was doing the killing off. He took to screenwriting in his early 40s because he wanted to come home and tell stories about his heritage, on his own terms. “I’d read so many bad scripts as an actor,” he says. “I knew what not to do.”

He mined his Texas youth for the diner scene in Hell or High Water, which stars Jeff Bridges. A surly waitress takes an order from Bridges and his partner by asking, “What don’t you want?” It was a fixed-menu place where the only decision was to not have the corn or not have the green beans. “That actually happened to me and my father when we ate at a West Texas diner when I was about 19,” Sheridan says. “Almost word for word.”

Ancient History

The Bosque Museum in Clifton, about 20 miles east of Cranfills Gap, tells the story of the pioneers who settled the rolling hills beginning in the 1850s. “Nor-Tex” history dominates, but the most significant attraction takes visitors back more than 11,000 years to the original humans of Bosque County: the Paleoindians. The 600-square-foot Horn Shelter Exhibit replicates the ancient Paleoamerican burial site found by avocational archeologists near the Brazos River in eastern Bosque County. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the discovery, the museum recently enhanced the exhibit with interactive elements and a new layout.

Bosque Museum

The museum is open Thu.-Sat. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. 301 S. Avenue Q, Clifton. 254-675-3845;

The Bridges character was inspired by Sheridan’s cousin, Parnell McNamara, a retired deputy U.S. marshal who was recently reelected McLennan County sheriff. “Taylor showed an interest in law enforcement growing up,” McNamara says, “but he was just born for that ranch. He was really upset when his mom sold it.”

Sheridan’s screenplay for Hell or High Water, about a pair of brothers taking desperate measures to save their family’s West Texas farm, was nominated for an Oscar. Holding on to your land is a perennial Sheridan theme.

“When you write, it’s always of an autobiographical nature,” he says. “Our family ranch has informed Yellowstone in many ways, but losing it was the biggest one.” While TV’s Dutton family turns to violence and intimidation to hold onto its territory, Sheridan’s family ranch was sold in 1991, after his parents divorced, while he was at Texas State University in San Marcos. “I don’t think Taylor spoke to me for a year,” says his mother, who had decided she couldn’t run the ranch alone.

Sheridan thinks about the feelings attached to his family’s old spread when he writes episodes for the show he pitched to Paramount as “The Godfather on the biggest ranch in the country.” Yellowstone is high drama in Big Sky Country—an addictive “rope opera” reminiscent of Dallas. But the show also hits home with those raised in rural communities because of its authenticity.

Sheridan remains an avid equestrian who’d rather go to horse shows and rodeos than the movies. His wife, Nicole Muirbrook, feels the same. The Utah-raised model and actress joins her husband for rides on their reining and cutting horses on the new family ranch an hour west of Fort Worth. Was there any chance the Sheridans wouldn’t raise their son, Gus—named after a character in Lonesome Dove—on a Texas ranch?

“Everybody wants to be a cowboy,” Sheridan says. “It’s a romantic way of life. But it’s rarely portrayed realistically in Westerns. We want to show the real cowboy life.”