Inside Sacred Heart Church in El Paso’s Segundo Barrio, the Rev. Rafael Garcia, SJ, hands out face masks in preparation for a colleague’s speech on the significance of the historic grounds we’re about to tour. It’s a cloudy morning in July, and there are about 80 people here. They wear yoga pants, sweats, and shorts; comfortable shoes; hats and sunglasses. Some have cameras hanging from their necks. Others smell of sunscreen. All are ready to partake in the Segundo Barrio’s first architectural walking tour, led by Max Grossman, who holds a doctorate in art history from Columbia University and is an associate professor of art history at the University of Texas at El Paso.

Sacred Heart Church

602 S. Oregon St., El Paso.

915-532-5447;

sacredheartelpaso.org

“Sacred Heart Church is the most important, historic, and iconic building in the Segundo Barrio,” Grossman says a few moments after the church bell rings nine times. “It’s symbolically important for the poor and underprivileged—it’s a symbol of hope.” As he talks, a woman sitting in the third row fans herself with a piece of paper she’s folded over twice. She briefly pulls down her face mask to wipe the sweat from around her nose and upper lip.

Grossman continues with a quick history of the Segundo Barrio, or Second Ward. He explains how the city of El Paso has often neglected the working-class Mexican neighborhood sandwiched between downtown and the Rio Grande. How in the 1910s the city tried to destroy many adobe homes in the Segundo Barrio, claiming them unhygienic. How after World War II, the neighborhood further deteriorated. Despite these “historic injustices,” he is able to end his talk on a positive note, declaring the Segundo Barrio on track to earn status as a national historic district. He is optimistic this will transform the neighborhood and help make up for the past.

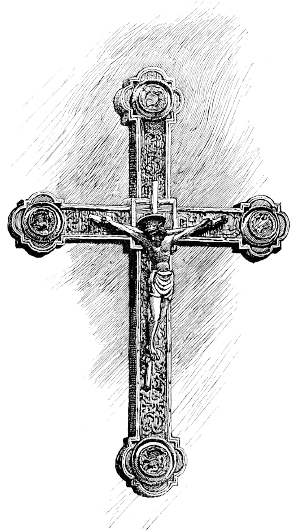

Following unanimous approval by the Texas Historical Commission this spring, the Segundo Barrio National Register Historic District is expected to become official by the end of November after final approval from the National Park Service. The designation comes with tax credits Grossman and Garcia hope will spur building and apartment owners to restore neighborhood structures that are falling apart. Part of the money will go to Restore Sacred Heart Church, a committee formed in 2020 to rehabilitate three buildings collectively known as Sacred Heart Parish. In addition to the current church—opened in 1923 and replacing the original church built in 1893—the parish includes the Sacred Heart School, opened the same year as the original church, and the Jesuit residence, added in 1898. Grossman and Garcia, who co-chair the committee, explain that all money raised from today’s walking tour—there was a second tour in late October, with more planned for the future—will go toward restoration efforts.

By extending the life of Sacred Heart, perhaps the Segundo Barrio’s soul can survive. The neighborhood and the church have grown interconnectedly. To help one is to help the other.

Felipe Peralta and his family moved to the Segundo Barrio from the Mexican state of Zacatecas around 1958. It didn’t take long to realize Sacred Heart’s importance. As a teenager, Peralta practically worked there, organizing sports through the church for youth back when they had to stay cautious of which streets they walked through since neighborhoods within the Segundo Barrio had gangs.

“Instead of fighting with each other, we gave them an opportunity to play sports,” Peralta remembers. “We would ride around in a pickup truck, go to different neighborhoods, pick them up.”

Some places Peralta drove through no longer exist the way they once did. Alamo Elementary School, which Peralta attended, is there physically but has been closed since 2007. Outright gone is Peralta’s childhood neighborhood, Rio Linda, which once stood on the northern banks of the Rio Grande. As part of the 1964 Chamizal Treaty, Peralta’s home was among the 630 acres the United States returned to Mexico to settle a land dispute, which arose when the river flooded in 1864. The flood shifted the border between Texas and Mexico. When that centurylong land dispute got settled, neighborhoods like Rio Linda disappeared.

Despite losing his home, Peralta continued attending Sacred Heart for special occasions—baptisms, marriages, funerals—while performing volunteer work around the Segundo Barrio. Eventually, Grossman and Garcia enlisted him to join Restore Sacred Heart Church. Because maybe better than anyone else, Peralta knows the hurt of losing a community.

“There’s always a fear and threat of what can happen to the barrio,” Garcia says a few days before the walking tour. Like Peralta, Grossman, and 24 other members of Restore Sacred Heart Church, he worries that even if the Segundo Barrio remains in name, its essence will vanish. That more homes will get destroyed and replaced with “a Starbucks or a Gap store or whatever,” Garcia says. “The barrio needs help.”

The church restoration will take three to five years, at a cost of $6 million to $7 million. With the money, the brickwork, crumbling in some spots from a century’s worth of wind, sun, snow, and rain, will finally be repaired. The spire and bell tower, too. Bathrooms will become handicap accessible. Floors will get replaced—and since they have asbestos, it will cost extra. A pipe burst this past winter, so plumbing also needs upgraded. Installing a new air conditioner is a priority because rising summer temperatures have made the church’s evaporative cooling system so useless that even while sitting inside during a cool, cloudy morning, doing little else besides listening, one can’t help but sweat.

As money is raised, repairs will happen in phases. Garcia, who has an infectious high-pitched laugh, jokes that if Jeff Bezos donates all the money, the church’s restoration will happen a lot quicker. But the reality is that apart from grants—in late October, the National Fund for Sacred Places awarded the church a $250,000 grant for restoration—Sacred Heart will get rebuilt in much the same way the church funded its construction in 1923. According to a December 1929 El Paso Herald article: “Weekly collections were chiefly represented in nickels and pennies.”

During the walking tour, Grossman—who wears a cowboy hat that casts a shadow to his chin—points at murals that tell part of the Segundo Barrio’s history. There’s one of the Rev. Harold Rahm, a priest who rode his bicycle around the neighborhood. He’s the same priest who hired a teenage Peralta to work with the barrio’s youth. That decision helped forge Peralta’s path, leading him to earn a doctorate in social work from the University of Texas at Arlington. “I like to think of the term, ‘It takes a village,’” says Peralta, who continues to work in the neighborhood. “In my case it was the Segundo Barrio that made it all possible for me.”

As the tour group walks at a leisurely pace from one place to the next, Garcia often stays behind. He stops to talk with residents who reach their hands out toward him. “There’s still a sense of neighborhood. People know each other, sit down to talk with each other. It would be a real travesty to destroy that,” Garcia says. “Buildings need improvement, people should be uplifted, slumlords need to be held accountable.”

A Day in the Neighborhood

Explore the history of the Segundo Barrio via these buildings.

Colón Theater

Once one of the most important Mexican theaters in the southwestern United States, it is the only art-deco building in the Segundo Barrio.

507 S. El Paso St.

Teresa Urrea Residence

Folk saint Teresa Urrea lived in the Segundo Barrio while in exile from the Mexican government, which charged her with inspiring rebellion. She survived multiple assassination attempts while living here.

500 S. Oregon St.

Pablo Baray Apartments

Located across the street from Sacred Heart Church, the site is where exiled writer Mariano Azuelo completed and published The Underdogs. It remains one of the most influential novels about the Mexican Revolution.

609 S. Oregon St.

Book walking tours of the Segundo Barrio through The Trost Society, trostsociety.org.

Grossman points at old buildings he loves as the tour continues. He indicates the general direction where other buildings once stood: hotels, theaters, brothels, saloons, opium dens. He identifies a corner lot just outside the boundaries of the Segundo Barrio. There, Grossman says, the remains of Juan María Ponce de León’s adobe house are 15 feet beneath the surface. In 1827, Mexico gave Ponce de León a land grant on the northern banks of the Rio Grande. That land became El Paso. And part of Ponce de León’s home was buried when the Rio Grande flooded.

But no matter which buildings Grossman points to or what history he shares, it all returns to the church. It’s still the reason people are here on this Saturday morning. It’s where the tour begins and ends. “Restoring Sacred Heart Church,” Grossman says, “is a very beautiful, positive project that I think everybody can get behind.”