Parks Less Traveled

Take a stroll off the beaten path at Mother Neff, Fort Boggy

Fort Boggy State Park

Listen to this story

Don’t get me wrong, it’s good for all of us that people are enjoying our state parks. In 2009, approximately 7.5 million people visited one of our state parks, historic sites, and natural areas. In 2021, that number rose to almost 10 million. That’s an extra 2.5 million people getting a nature fix and coming home feeling a tad more relaxed, maybe a little bit kinder—and the world is better for it. So what if I must now reserve my spot on the state park website? It’s easy to use and helps the parks efficiently manage visitor volume.

But I still want my time with the rock. Once home, I log into the online reservation system to find the next available weekend campsite at Enchanted Rock is almost three months away. In Plan B mode, I scroll the list of parks and realize I’ve visited just 14 of the 89. That’s only 16%! What have I been missing by not expanding my park horizons? A bounty of unfamiliar Texas territories are begging to be explored, but first I have to figure out where to begin.

For a bit of guidance on the lesser known state parks, I reach out to Aaron Friar, Special Assistant to the State Park Director for the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. He shares a list showing how frequently each park is visited. I am not surprised to find Enchanted Rock at the high end of usage, way up at No. 6, in the company of my other favorites: Pedernales, Palo Duro Canyon and McKinney Falls. But I am surprised at the low visitation of a few, especially some of West Texas’ most sublime treasures: the Devils River; Big Bend Ranch (which, at over 300,000 acres, makes up about half of the parks system’s approximately 640,000 acres); and Fort Leaton, a handsome adobe dwelling with an intriguing past on the twisty river road between Big Bend and Presidio.

So why are these spectacular, remote spots visited so little? Apparently, it’s because they are so remote. “A lot of folks don’t like to drive more than an hour and a half to a park,” says Friar, who has visited all the parks. “And so, with some of these parks you must really, really want to get to them. For example, Kickapoo Cavern, I absolutely love that park. It’s got caves, a lot of natural resources, and it’s a beautiful park, but you have to want to get there.”

And then, of course, there’s the size of the park—obviously fewer people can visit a park with just a handful of campsites than they can a park like Garner, which is bursting at the seams with 354. Differences in amenities impact usage, too: Some folks will only go to parks with full hookups for their RVs, and some don’t want to drive miles of dirt roads, as you must at Big Bend Ranch. “We know that not everybody starts out in a tent,” Friar says, “so we try to offer a balance from the most remote primitive backcountry experience all the way up to new cabins and full-service amenities.”

It’s time I get to know some of these less-visited parks. I want to find out who the mother is behind Mother Neff State Park and why Fort Boggy—located just about an hour and a half east of Waco—ranks No. 4 on the list of least-visited parks. I lace up my hiking boots and head out.

Mother Neff State Park

Nestled in 259 acres of rolling prairie and limestone canyons near Temple, Mother Neff is small but plays an outsize role in the story of our park system. The eponymous Isabella Neff purchased the land with her husband in 1852 when they arrived from Virginia; here they built a community, hosting picnics with neighbors along the Leon River. Before she died in 1921, she willed the riverside property to the state, indicating that the land was to be used as an outdoor, public gathering place. Her son, Gov. Pat Neff, would see to it that his mother’s vision was made a reality: In 1923 he persuaded the Texas Legislature to establish the State Parks Board, and the state park system was born. Gov. Neff donated the 250 acres of family land to the state, and Mother Neff State Park officially opened in 1937. A Civilian Conservation Corps crew constructed roads, trails, picnic areas, and campgrounds on the site from 1934 to 1938.

Hiking the park’s two-mile loop through ashe juniper and moss-softened limestone on a sunny March morning, I give a little bow to Mother Neff and her son. They were among the first private donors to give up their land to share with all of Texas; since then, our state parks system has depended on the donations of private landowners to grow. Thanks to their generous vision, this morning I can hear six layers of bird songs including the staccato call of the golden-cheeked warbler, an endangered bird who uses strips of bark from these juniper trees to make its nests. Happily, this sweet bid symphony is pretty much all I can hear on this shady green path so removed from the hustle of the highway.

I had hoped to spend the night at one of Mother Neff’s primitive campsites close to the Leon River, but that section of park has been closed since 2015 due to repeated flooding. The park’s infrastructure has since been shifted to higher ground—Mother Neff is now home to a handsome new limestone headquarters overlooking a butterfly garden and fields of bluebonnets. Also new (and uphill) is a stretch of 20 full hook-up RV sites and pristine bathrooms, which have received stellar online reviews from the RV community. “Another reason people come here a lot is that we have the Buc-ee’s of the camping restroom world,” says Angelina Fontenot, the park’s office manager. “Everyone loves how nice they are inside.”

Not wanting to pitch a tent next to an RV, I am happy settling for a day pass. My short hike leads me to the climbable stone water tower built by the CCC in the ’30s, to a rock shelter thought to have been inhabited by Tonkawa, and to a small pool called a Wash Pond. Although it is not open for swimming, I like to imagine Mother Neff here enjoying a dip. Surprised by just how happy I am alone in the woods, I think of the words of Gov. Neff; in a speech, he once called our natural spaces “breathing spots for humanity.” Even after just a short walk here, I feel how easy it is to breathe in these oxygen-soaked woods.

Fulfilling Mother Neff’s wish, her land is still a gathering spot for locals today. Many of them grew up attending weddings and religious events in the park’s Rock Tabernacle, which was also built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. This section of the park has been closed since 2015 due to flooding; its rebirth awaits. Despite the closure of the park’s bottomlands, an average of 75 people come daily just to get some fresh air. “Even their dogs are regulars,“ says Fontenot. “They know where the treat box is when they pull in with their owners.” Fontenot says one man shows up early every morning and takes photos, which he then shares with the park. “He’s always here. He might miss three days a year,” she says.

While this park may lack Enchanted Rock’s dramatic landscape, it more than makes up for it with unrivaled quietude and other small-park charms. With no lines of cars or crowds to worry about, I’ve remembered a truism that is easy to forget when I spend too much time in front of a computer screen: Even a little dose of nature can lift my spirits.

“Our goal is to try to introduce the outdoors to the community,” Fontenot says. “The more we can get kids out enjoying nature and not inside playing video games, the better. It’s good for the whole community.” Because whether the kids know it or not, they need their breathing spaces too.

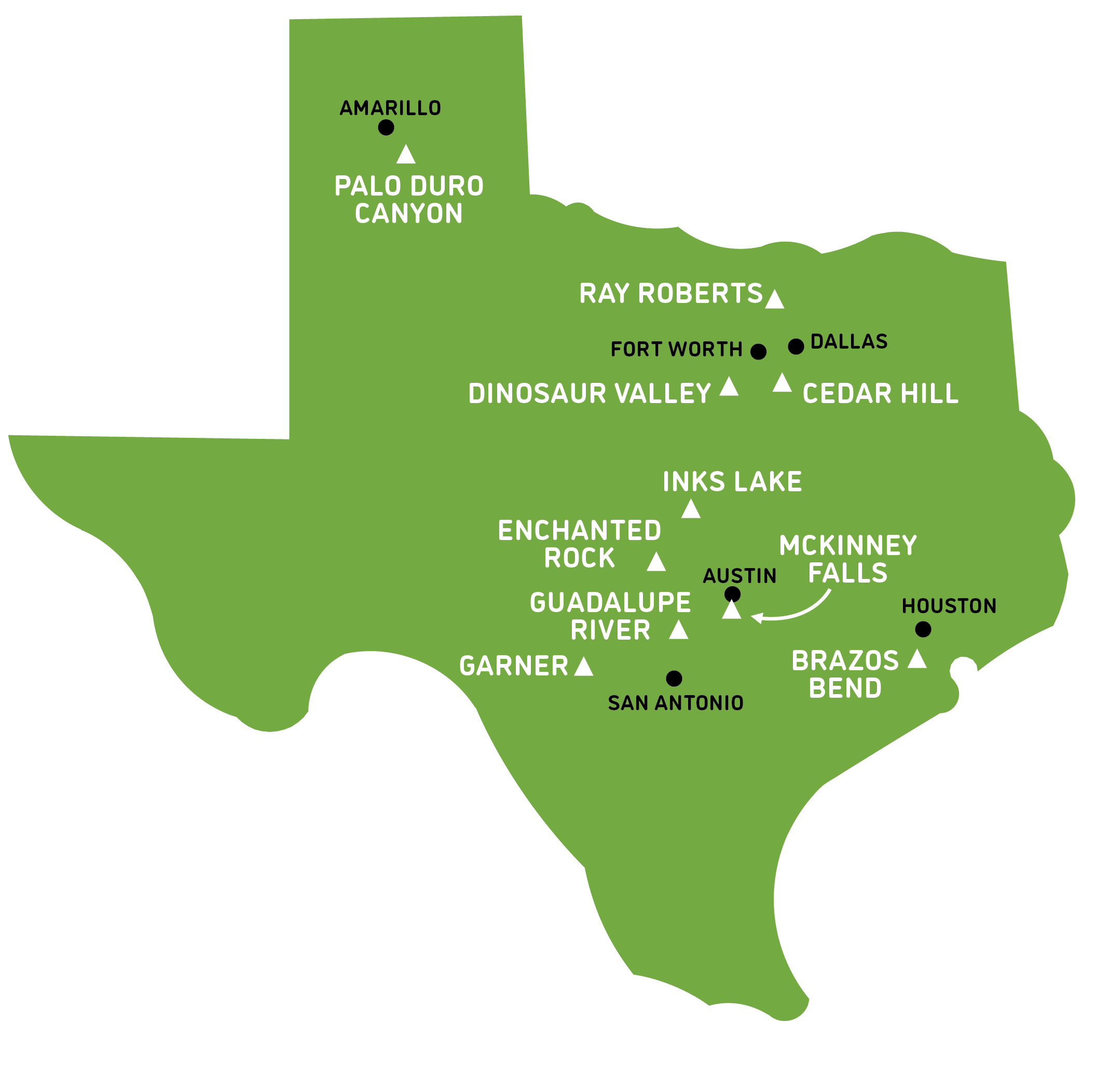

Most Visited State Parks

Ray Roberts Lake, Pilot Point

Garner, Uvalde

Palo Duro Canyon, Canyon

McKinney Falls, Austin

Cedar Hill, Dallas

Enchanted Rock*, Fredericksburg

Brazos Bend, Houston

Dinosaur Valley, Glen Rose

Guadalupe River, Bulverde

Inks Lake, Burnet

LEAST Visited State Parks

Kickapoo Cavern, Bracketville

Resaca de la Palma, Brownsville

Big Bend Ranch, Terlingua

Fort Boggy, Centerville

Mission Tejas, Rusk

Lake Colorado City, Colorado City

Estero Llano Grande, Weslaco

Seminole Canyon, Comstock

Hill Country*, Bandera

Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley, Mission

*Enchanted Rock and Hill Country

are both State Natural Areas.

Rankings based on 2022 paid visitation data, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife. A ‘less-visited’ park does not necessarily imply the park will be less full due to variations in amenities and capacity. Always check with the park or make a reservation to ensure a smooth visit.

Parks Less Traveled

While no two parks are the same, here are some off-the-radar alternatives to the state’s busiest parks:

Love Enchanted Rock but can’t get a spot? Explore the natural rock outcroppings and prehistoric cave paintings of Seminole Canyon State Park & Historic Site.

If Garner State Park is packed, consider South Llano River State Park, another cool water refuge. With over 22 miles of hiking trails to explore, you can get lost in nature and still take a river plunge.

Palo Duro Canyon is a rocky Panhandle wonderland, but the lesser-known Caprock Canyons State Park and Trailway nearby comes with a big bonus: Its sweeping canyons are the happy home of Texas’ last herd of Southern Plains bison.

While the footprints of dinosaurs can be found at popular Dinosaur Valley, quieter Copper Breaks is a majestic refuge where Quanah Parker and other Comanche warriors once traveled.

If the speedboats leave no room for your canoe at Inks Lake State Park, mosey over to the spring-fed lake at Fort Parker State Park, where you can paddle in peace.

Fort Boggy State Park

From Mother Neff, I head to Fort Boggy, about a two-hour drive to the edge of the Piney Woods of East Texas. Located just south of Centerville, Fort Boggy is like Mother Neff in that it’s a small park with low visitation but exudes charm nonetheless. Fort Boggy only has five primitive camping spots and five cabins, all burrowed into a forest of phosphorescent green sweet gums, elms, and even river birch trees—the only species of birch native to Texas.

Also like Mother Neff, Fort Boggy is rich in Texas history. Early settlers built Fort Boggy in the 1840s and enlisted members of the recently formed Texas Rangers to protect them from the Kickapoo and Keechi Indians who first lived in the area. The Anglos’ wooden fort in the woods has long since disintegrated—a historic plaque is the only visible reminder that this now-peaceful park was once the setting of a fight for survival.

When I check into the modest portable building that serves as the park headquarters, office manager Eduardo Virjan hands me the key to the cabin I’ve booked for the night and says, “If you want to be alone, you’ve come to the right park.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. As I haul my sheets, blankets and pillows from my car to Cabin Four (most cabin rentals in state parks require that you bring your own bedding), I don’t hear another human anywhere in the park. I arrive at my spacious slope-roofed cabin to find the gravel in its outdoor picnic area meticulously raked, welcoming me like a Zen garden. Although the cabin’s screened porch is big enough to host a cocktail party, all I want to do is to sit and read and listen to the impressively loud cicadas and frogs who call this vivid green park their home.

But first there are introductions to be made. I visit J.D. Miller, the park superintendent who lives on the property with his wife. With a reddish goatee and sparkly blue eyes, he invites me for a park tour in his pick-up with the pride of a dedicated steward. After he took charge here just over five years ago, he worked with his regional director to get funding for a full-time interpreter, the park employee who oversees education and events for visitors. Now, Miller and his team offer night hikes, kid fishing events, and glow-in-the-dark Easter egg hunts, all of which have surpassed turn-out expectations. Nearly 40 people showed up for their first night hike. “One of our goals with interpretation is to get the parents involved,” he says. “For our first Easter egg hunt, we had every parent out there with their child and helping. It’s what we love to see.”

Other than woods—so glowingly green you can almost smell the chlorophyll—the natural star of this park is the 15-acre Sullivan Lake, a swimming hole encircled by woods that feels more like Walden Pond than a Texas lake. Fed by three natural springs, the water maintains 72 degrees at its deepest point. Miller is proud that Sullivan Lake is still home to trout when other Texas lakes get too warm for the fish, which favor cooler water. “We are still catching trout here in June and July,” he says. The pond is named for the Sullivan Family who donated this land to the state parks system in 1985– yet another example of generous landowners sharing their bounty with the rest of us.

Ready, Set, Tent

To appeal to Texans’ varying preferences for outdoor fun, the state park system has brought in a company called Tentrr, which sets up a simple, canvas-walled tent with cots, an Airbnb for camping. “You show up to the park and go right to your tent, just bringing in food and sleeping gear. People seem to really like it,” says Friar. Tentrr now has operations at multiple parks, including Galveston Island, Brazos Bend, and Guadalupe River State Park. Sites start at $79; book at tentrr.com

With its quaint summer camp feel, Fort Boggy might not stay quiet for long. “We are such a small park,” Miller says, “people drive past and don’t even know we are here, but once we get them in the gate, we see them over and over. They say, ‘We’re not going back to those bigger parks. They’re too busy and crowded.’”

I sleep that night with my cabin windows open so I can hear the hum of the forest, nature’s sound machine. In the morning, after a two-mile hike on a path so embowered in green that it’s called the Tunnel Trail, I stand on the dock of Sullivan Lake. I am the only person around. It may be a cool overcast spring morning, but that’s not stopping me. It’s not every day you get a whole lake to yourself. I count to three, jump in, and breaststroke to the lake’s small floating pier. I pull myself out to lie flat on its surface, every cell vibrating and happy. I’ll always hold close those moonrises at Enchanted Rock, but this may be my best state park moment yet.