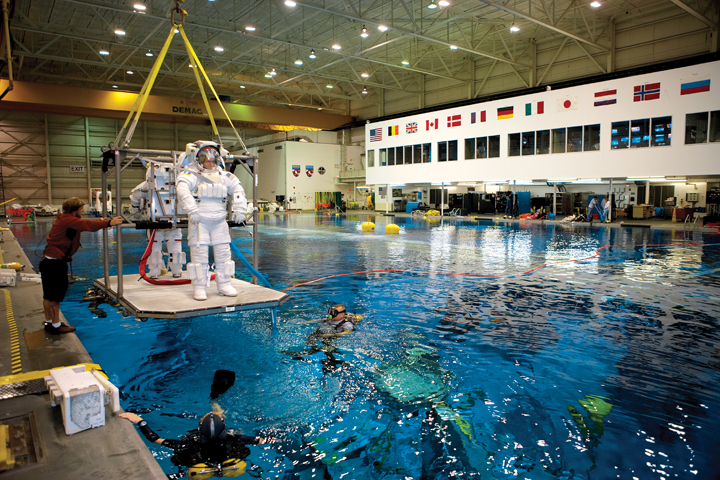

While it’s impossible on Earth to experience the zero-gravity challenges of space, astronauts can get pretty close in the 6.2 million-gallon pool known as the Neutral Buoyancy Lab, the centerpiece of NASA’s Sonny Carter Training Facility. (Photo by Kirk Weddle)

Forty years ago, on July 20, 1969, millions of Americans sat riveted to their television sets as they watched astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon and speak those memorable words, “The Eagle has landed.” This “giant leap for mankind” would not have been possible without Houston’s own Johnson Space Center, which coordinated the historic Apollo mission.

Created in 1963 to fulfill President Kennedy’s ambition for the United States to reach the moon before the close of the decade (and before the Russians), this center has been at the heart of NASA operations since the early days of the space race. Lyndon Johnson, a senator at the time of the 1957 Soviet launch of Sputnik, had spearheaded legislation to bring the project to Texas, and had suggested Houston as an ideal location, due to the city’s mild climate, status as a major port, and established university research facilities.

The Johnson Space Center became NASA’s hub for astronaut training and the home of Mission Control. Over the years, the center has developed, guided, and monitored numerous crucial missions, such as the early Mercury and Gemini projects to put astronauts in orbit around the Earth, the Apollo moon missions, the subsequent Space Shuttle flights, and the construction of the International Space Station. Currently, the center is in the planning phases of its next big project: the Constellation program, a new initiative to return to the moon by 2020.

The Johnson Space Center’s campus of about 100 buildings stretches across 1,620 acres in the Clear Lake area, southeast of downtown Houston. Approximately 18,000 people work there, including private contractors, government employees, and a corps of about 110 astronauts, but public access to the site is limited due to security issues. To make the space program more accessible to the general public, the Space Center Houston opened here in 1992 to offer visitors hands-on experiences and space-themed exhibits.

Yet, as I recently discovered, you can still experience the “real” Johnson Space Center by signing up for a Level 9 Tour, a five-hour, behind-the-scenes look at the sprawling NASA campus. These weekday tours, limited to groups of 12 people age 14 and older, are essentially field trips for grownups.

The tour begins at Space Center Houston, where my fellow tour-goers and I meet Georgene Harris, a peppy NASA expert who has made a second career as a part-time Level 9 Tour guide. Donning our VIP badges, we follow Harris through a security checkpoint and pile into a van, which whisks us away to our first stop, the NASA cafeteria, where we enjoy lunch among astronauts, mission-control officials, physicists, and other employees. Harris serves as a celebrity-spotter of sorts, pointing out the important players in the space program, nodding discretely in the direction of three astronauts sitting just two tables away. There’s a heightened sense of possibility even in the employee mess hall, and we can’t wait to see more.

Back in the van, we wind through a maze of nondescript beige buildings lining a meandering drive. Some sites are still off-limits, even to VIPs like us, for security reasons. Harris indicates where the pyrotechnics are tested, where Space Shuttle flight simulations take place, where astronauts are quarantined prior to space travel, and where 800 pounds of moon rocks are stored for research.

We pull up at the Sonny Carter Training Facility, where astronauts learn how to maneuver in weightless conditions. The building is home to the Neutral Buoyancy Lab, a 40-foot-deep swimming pool that measures 102 feet wide and 202 feet long; it holds 6.2 million gallons of water. Harris leads us along an enclosed catwalk overlooking the immense pool, where we observe two astronauts in spacesuits practicing to make repairs on a full-scale model of the space station. They’re at the bottom of the pool, surrounded by a team of support divers, one of whom transmits live video footage to monitors mounted in our walkway. We watch in fascination as one of the astronauts struggles with an underwater drill. Harris informs us that the astronauts train in the pool for six hours at a time, without a break, in order to prepare themselves for the rigors of an actual spacewalk. “These are the people blazing the trail for future generations in space,” she declares, before dragging us reluctantly back to the van.

Astronaut training is one of the Johnson Space Center’s main endeavors, but ground-crew training is just as essential to the space program. For our next stop, Harris brings us to the first of the center’s three mission-control centers, where NASA staffers practice simulated Space Shuttle missions to test their emergency responses and hone their problem-solving skills. The room is filled with state-of-the-art equipment and banks of computer monitors, and when it is not being employed for training, it functions as mission control for Space Shuttle flights. Today we are in luck, because we arrive just minutes after the shuttle has returned to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. From a viewing chamber at the back of the room, we watch televised footage of the shuttle being guided down the runway as the mission-control crew interprets vast data streams. We proceed down a hallway to see the second mission-control center, which is used for monitoring the International Space Station (ISS)—an Earth-orbiting research facility constructed and manned cooperatively by NASA, the European Space Agency, and the space agencies of several other nations, including Russia, Canada, and Japan. Unlike the first control room, this one is in constant operation. Because the ISS is in continual orbit, the mission is ongoing, and the ground-control staff work in shifts to monitor the data coming in. A screen at the front of the room shows a real-time map tracking the ISS’s progress as it orbits the earth. Two flanking screens display views from the space station, one of which shows the Earth blanketed in a swirling mass of clouds as it gradually passes from daylight into darkness.

Our next stop brings us to Apollo Mission Control, now a National Historic Landmark. Unlike the other two mission-control rooms, this one, which monitored the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions, is no longer operational. With its miniscule computer monitors, rotary phone dials, and push-button module, it appears untouched by the intervening years of technology. Tour guide David Cisco, a 40-year veteran of NASA, joins us, sharing firsthand stories of the groundbreaking events that took place in that room. Here’s the desk, Cisco tells us, where flight-control personnel heard the words “Houston, we have a problem” during the nearly doomed Apollo 13 mission. He holds up a slide rule, impressing upon us the fact that it was really people doing work “north of the eyebrows” who made those first forays into space possible. Despite the size of those early computers, Cisco says, they had a capacity of only about 400 kilobytes: “There’s more technology under your car’s dashboard these days than what we used to send 12 astronauts to the moon.”

With a renewed sense of wonder, we pile back into the van to see what Harris refers to as the “big toys” in the Space Vehicle Mock-up Facility. This vast, open building is packed with space contraptions, including full-size mockups of the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station. Here, robotics experts test prototypes, engineers refine design plans for ISS components, and astronauts familiarize themselves with various equipment and space vehicles. Although we aren’t permitted to venture inside any of these incredible “toys,” we can gawk to our hearts’ content as we wander about the room, which is littered with an unbelievable assortment of tools, spare parts, spacesuits, and lunar rovers. Harris draws our attention to several robots, including the Robonaut Senetor, which looks like an oversized Transformer toy (part astronaut, part four-wheeler) and will collect soil samples on future missions.

We look forward to our final stop: a Saturn V rocket, identical to the ones used to launch astronauts into space during the Apollo missions. Housed in a protective hangar at NASA’s Rocket Park, this magnificent rocket rests on its side; upright, it would stand as tall as a thirty-story building. This particular rocket is one of only three Saturn Vs in existence; its predecessors were destroyed during the course of the missions, and this one was spared only because the program was cancelled before it could be launched. We walk the length of the rocket, admiring its enormous size, the know-how that went into creating it, and how far we have come in our explorations of space since that time. Now, 40 years after that first lunar landing, NASA is once again setting its sights on the moon, and the Johnson Space Center stands ready to guide the footsteps of those making that next giant leap forward.