The Dry Creek Cafe and Boat Dock opened on Mount Bonnell Road in the hills of west Austin in 1953. Photo by Sarah Thurmond.

Back in the day, the Dry Creek Cafe and Boat Dock was the place that clued you in to the fact you were in Austin now, not somewhere else in Texas. It was part of your introduction.

After walking up Mount Bonnell, the promontory with a sweeping vista of the city and highest point in the city, you drove down Mount Bonnell Road to 4812, the address of the offbeat two-story ramshackle structure with a counter, mismatched tables and chairs, a jukebox to die for, and a bare upper deck with a sweet view of the hills west of Austin.

It was all overseen by a surly owner-barkeep named Sarah Ransom, who didn’t take no mess and would call you out if you didn’t return your beer bottles to the counter when you were done. She did not like to climb the rickety wooden steps to the deck to retrieve empties. The first time she yelled at you, you felt like you belonged.

There was neither a cafe nor boat dock, but no one seemed to mind. Unlike most other beer joints in Texas, hippies and college students outnumbered the rednecks and day drinkers.

There was a time the Dry Creek Cafe and Boat Dock did serve burgers prepared by Ransom—when she felt like it. She quit feeling like it a half century ago.

On Oct. 31, the Dry Creek wraps up its illustrious Austin-defining run that began in 1953. The city finally caught up with it. The rural outpost once hidden away in the cedar breaks is surrounded by multimillion dollar homes today.

The interior of Dry Creek Cafe and Boat Dock hasn’t changed in decades. Photo by Sarah Thurmond.

In 1984, Ransom sold Dry Creek to her son, Jay “Buddy” Reynolds, who kept his mother behind the counter as long as he could, followed by other legendary barkeeps over the four decades he owned the place.

Ransom died in 2009 at the age of 95. Affectionately called the “meanest bartender in Austin” by the late Austin American-Statesman columnist John Kelso, she is immortalized in a T-shirt bearing her likeness and the quote, “Bring your bottle back down.”

After receiving “an offer I couldn’t refuse,” Reynolds, now 84, sold the property earlier this year. Despite attempts by loyal regulars to “save” Dry Creek, the deal is done.

Getting in one last goodbye are pianist-singer Marcia Ball, guitarist John X. Reed, and bassist Bobby Earl Smith, the core of Freda and the Firedogs, the influential early ’70s country-roots band that breeched the great hippie-redneck divide of Austin.

“When you got to the place you could kind of forget you were in the city,” says Reed, reminiscing. “It was funky. It had that thrown-together look. It was kind of a shack, everything old wood. And the upstairs deck with the wonderful view to the west, the hills and the trees. I’ve watched a lot of sunsets there.”

In 1972, Freda and the Firedogs recorded a murder ballad that Smith and his friend Ron Howard (not to be confused with the famous director) composed called “Dry Creek Inn.” The song appeared as a 45 rpm single, the format made for Dry Creek’s jukebox, and on Freda and the Firedogs’ sole album, recently reissued and distributed by Antone’s Records (copies are being sold at the counter for $20).

Smith, who first visited Dry Creek as a law school student in 1967 and wrote the lyrics to the dark song about a man who kills a woman and gets away with it, says he was inspired by the Kingston Trio’s then-popular “Tom Dooley.” Ransom, however, did not like how the song portrayed her:

If it hadn’t’ve been for Sarah

They’d’ve caught me

But she took me and hid me

Cooked for me and did me

But I never go again

To the Dry Creek Inn

Once she figured out the words, Ransom took the record off the jukebox, threw out Smith, and banished him from Dry Creek. “Alvin Crow told me Sarah was going to shoot me for the lyric about her,” Smith says.

The beef didn’t last, and the record returned to the juke. At her 90th birthday, she greeted Smith by wisecracking, “Look what the cats dragged up. Did you bring me my record?”

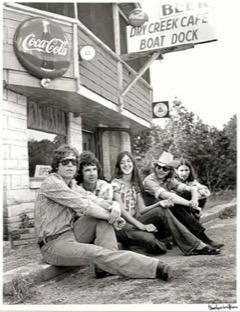

Freda and the Firedogs had their first photo shoot at Dry Creek. Photo by Burton Wilson.

For Marcia Ball, Dry Creek’s closing “is the capital letter End of An Era,” she says, adding that the building should be given a historical marker designation, along with the dancehall Broken Spoke and original Threadgill’s, both also in Austin. “They are no less important than the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville.”

Dry Creek was where the Firedogs had their first photo shoot, but it wasn’t the first time Ball visited it. “I had been there once before because we had a friend living on the creek a little ways down Mount Bonnell Road,” she says, “but being resolutely South Austin and also wary of what kind of reception our obvious long-haired hippieness would receive, we didn’t hang out there.”

While Ball says she never really got to know Ransom, she believes the late owner was the reason the place stayed open for as long as it did. “Sarah kept it going the same as ever, and her family supported her in her wish to preserve the tradition and helped her to do it,” she says, before rattling off a list of places where the Firedogs played that are no longer around including Lake Austin Inn, the Vulcan, Split Rail, Armadillo, and Soap Creek.

“The Dry Creek Inn was there before and outlived them all in spite of being wedged into a corner,” Ball says. “I just hate to see this piece of Austin history go.”

Tomorrow, Freda and the Firedogs plan to return for an interview and unplugged performance of “Dry Creek Inn” in front of film cameras (unfortunately, it’s closed to the public). It will be a last look back and one more sunset at the “funky” little spot.

If heading out for the final sunset viewing at Dry Creek on Sunday, Oct. 31, bear in mind that they only serve beer and only take cash. And don’t forget to return your empty bottles.