Frida Kahlo’s “Still Life” (1951). Photo courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art.

Frida Kahlo’s life and art have taken on mythic dimensions since her death in 1954. During her lifetime, she suffered the physical ravages of polio, a spine-shattering bus accident, and a tumultuous marriage to the Mexican painter Diego Rivera, all of which manifested in her art, sometimes in a symbolic fashion. Certain works by Kahlo are instantly recognizable, particularly those featuring her distinctive face. However, many others are less familiar yet nevertheless reveal much about her artistic process.

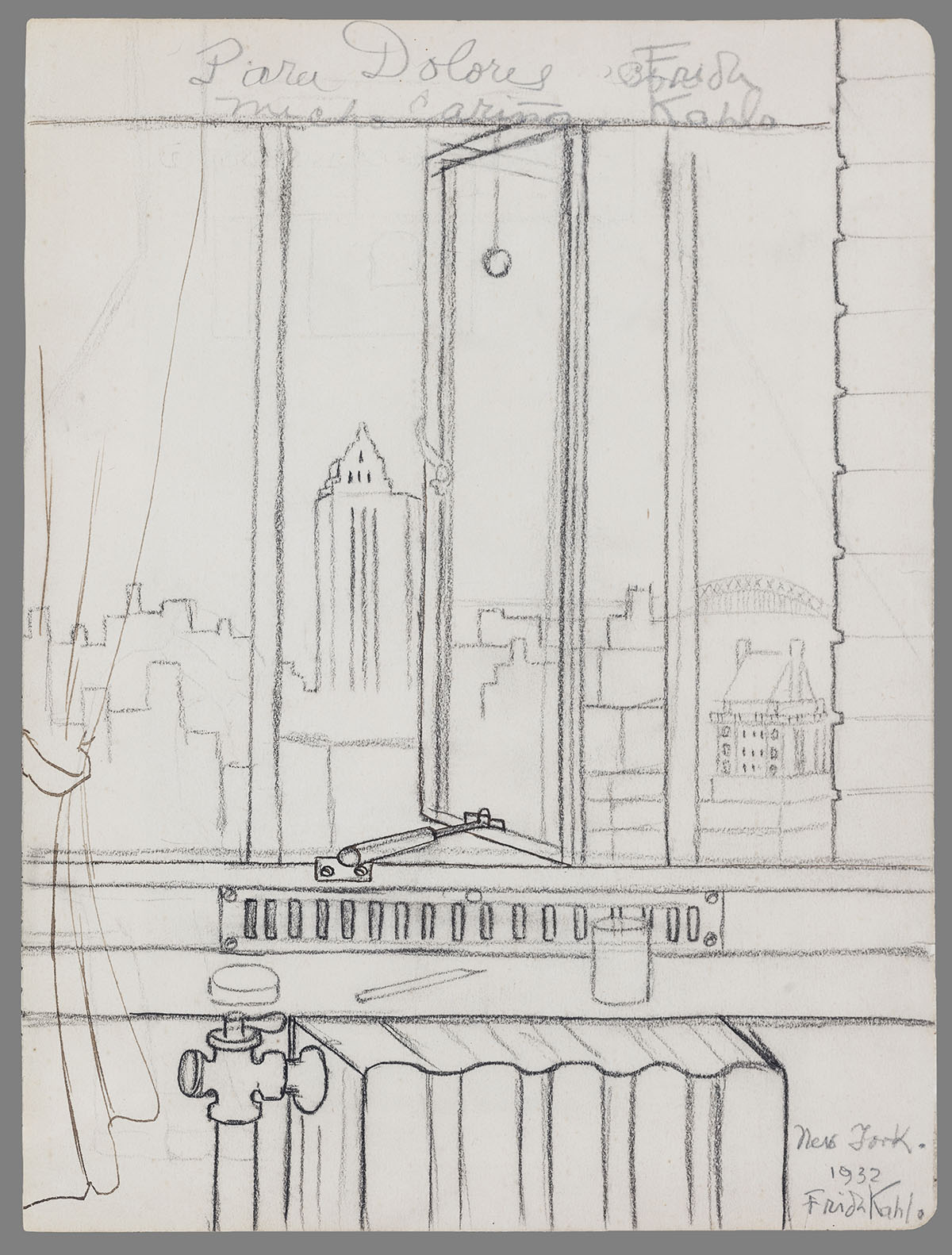

“View of New York” (1932). Photo courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art.

March 7-June 20, the Dallas Museum of Art showcases five of the artist’s more obscure works, which come to Texas via an unnamed private collection in Mexico. Although small in scale, the exhibition, Frida Kahlo: Five Works, allows for each of these artworks to serve as a wider window onto Kahlo’s life and artistic process. As Mark A. Castro, who curated the exhibition and is the museum’s Jorge Baldor Curator of Latin American Art, says, “When you show less, it can encourage people to look more closely.”

The earliest work in the exhibition, View of New York, is a simple pencil drawing from 1932 that captures what Kahlo saw from the apartment window where she had been staying in New York City with Rivera while he was working on a commission. Castro points out that Kahlo took pains to portray the details of the radiator and the crank-operated window. Even though the artist was critical of capitalism in the United States, the piece also conveys her fascination with the country’s modern conveniences.

It’s details like this—along with the artist’s willingness to lay so much of her life out in the open—that continue to make Kahlo such an appealing figure to audiences. “The reason that we often talk so much about her biography when we talk about her works is that they do seem very personal and seem to touch on events in her life,” Castro says. “I think there’s a great deal of empathy in her work that people can connect to on an emotional level.”

“Diego and Frida 1929-1944,” an oil on masonite in original painted shell frame. Photo courtesy Dallas Museum of Art.

The other four works in the collection, all oil paintings on Masonite, are less literal in their depictions. Diego and Frida 1929-1944 (dated 1944) encased in the original shell-encrusted frame, commemorates the couple’s 15-year anniversary through symbolic iconography: a sun and a moon, a mollusk and a conch shell, and a split portrait of the artist and Rivera. This combination of opposites reflects how the couple, despite sometimes being in opposition, could not survive without one another.

Frida Kahlo’s “Still Life with Parrot and Flag” (1951). Photo courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art.

The sun image appears again in Kahlo’s painting Sun and Life (1947), nestled amid plants with veiny leaves and womblike pods, one of which holds an embryo. While making this work, Kahlo made adjustments to the composition with each layer of paint, as recently uncovered in an x-radiograph (an imaging technique using X-ray technology) taken by a museum conservator, who performed this technical analyses on two other works as well. The revelations from those investigations are also included in the exhibition.

In Kahlo’s final years, when she was limited in mobility due to her failing health, she was drawn to still-life subjects. Two of her paintings from 1951 display tropical fruits, along with other references to her home country.

Frida Kahlo’s “Sun and Life” (1947). Photo courtesy Dallas Museum of Art.

“She was really interested in grounding her compositions in her own identity, and so everywhere you see these signs of Mexican life, whether through the selection of fruits, the inclusion of these little simplified Mexican flags, the Colima dog vessel, or the parrot. With these, she’s really evoking herself and her place in the world,” Castro says. “What I love about Kahlo is that, when you cut through all of the hype and the incredible stories of her life, there’s just this amazing artist at the heart of it all.”

Frida Kahlo: Five Works can be seen for free as part of the Dallas Museum of Art’s free general admission policy. A timed ticket secured in advance is required in order to maintain a limited capacity.