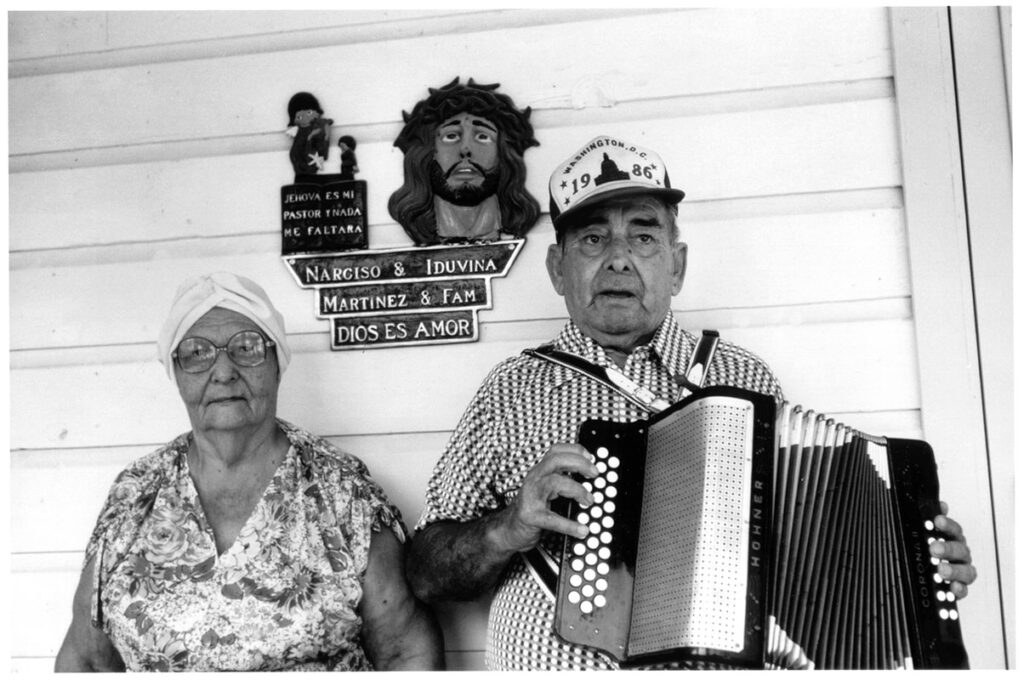

Iduvina and Narciso Martinez at home in San Benito, Texas. Photo courtesy Arhoolie Foundation.

Today marks the 110th anniversary of the birth of Narciso Martinez, the inventor of conjunto music and a man whose sound has spread far and wide, becoming as identifiably a part of the Texan landscape as bluebonnets and Longhorns.

It is also the 30th birthday of the cultural center that bears his name in San Benito. There is no structure, per se, bearing the name Narciso Martinez Cultural Arts Center. Rather, in the vision of its director, Rogelio Núñez, the town itself is the cultural center for a certain pueblo, or people.

San Benito is the home of both Martinez and the town’s other musical hero, the late Tejano and country star Freddy Fender. It’s where the Ideal Records label helped put conjunto on the map, and it’s the site of the recently restored La Villita Dance Hall, where people cut a rug to it.

There are humbler institutions as well. “La Especial Bakery is still there, right down the street from La Villita,” Núñez told writer Michael Rodriguez in Texas Highways earlier this year. “Even younger folks in San Benito identify with the bakery because it’s a place people talk about and find just by following the smell of bread.”

So, the whole town composes the cultural center, and in Núñez’s somewhat joking approximation, San Benito is the “center of the universe.”

The Narciso Martinez Cultural Arts Center holds concerts at La Villita; poetry and other readings at Iglesia Getsemani church; and the annual mid-October Narciso Martinez Conjunto Festival in Los Fresnos, just down the road.

In San Benito, the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame and Museum displays Martinez’s accordion along with those of the musicians he inspired. Exhibits also cover Ideal Records and La Villita and the hall of fame’s 79 inductees. There’s a shrine to Fender, as well as rotating exhibits of whatever they might have on loan at any given time.

Born just across the Mexican border from McAllen in Reynosa, Martinez spent almost all of his life in La Paloma, a tiny village long ago absorbed by burgeoning San Benito. He was brought across the river as an infant by his parents, who worked as migrant workers in the South Texas vegetable fields and grapefruit orchards. While there was no time for school, it was there that he first heard the ranchera music of his own people and the polkas and waltzes of the Germans and Poles of South Texas. The two sounds naturally melded in his mind, and by the time he was able to afford a Hohner accordion, as opposed to the one-button “la mugrita” (translating to English as “piece of junk”) he’d begun with, what came out was a fusion of the two cultures—the blueprint for conjunto.

He and bajo sexto player Santiago Almeida teamed up and soon found themselves kings of the South Texas dance halls. In due time, they went to San Antonio and successfully auditioned for a representative of Bluebird Records. With the singles “El Tronconal” (“The Trunk”) and “La Chicharronera” (“The Pork Skin Lady”), the duo was off to the races, recording dozens of songs and carrying their music all over Texas and the Southwest. They recorded dozens more records that spawned many an imitator, including Santiago Jimenez Sr., the father of Santiago Jr. Jimenez and Flaco Jimenez, who is today the personification of the genre worldwide.

Since then, that accordion sound born under the Rio Grande Valley sun and performed by Flaco’s swift fingers, has enlivened recordings by everyone from Dr. John to Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones, and perhaps most famously nationwide as the backdrop to Dwight Yoakam’s duet with Buck Owens on the hit “Streets of Bakersfield.”

Personally, this music has meant a great deal to me; indeed, I would say it has been life-changing. Along with the also accordion-based zydeco of the upper Texas coast, it has bound me to my native state as much as anything else.

As a proud native Texan, when my dad, music journalist and manager John Lomax III, had a job in the country music business that took our family to Nashville when I was 4 years old, I was constantly homesick, a malady partially cured by spending all major holidays and significant portions of each summer at my grandparents’ house in Houston. This homesickness was more or less constant, but certain sights and sounds would kick it up to acute levels.

One surefire sight was the Tex-Mex feast pictured on the gatefold of ZZ Top’s Tres Hombres album. Its platter of cheese enchiladas, tacos, chili con carne, tostadas, frijoles, and Spanish rice all arrayed near jars of lemon and lime and a frothy glass of Southern Select beer swept me back 750 miles southwest from the misty Tennessee hills to steamy Houston and family meals at Felix, a venerable old-school Tex-Mex temple.

And then there was the album Flaco Jimenez y su Conjunto, introduced to me by my San Antonian stepfather Chip Phillips. The wailing of Flaco’s accordion, the alternately mournful and exuberant vocals, and the thrum of the bajo sexto would both elate me and make me yearn to be home, where I would hear that music occasionally live in restaurants and mercados and often ambiently in the streets of Houston or on the radio if I chose to dial it up.

Back in Nashville, in the days before widespread videotapes, my dad would occasionally screen rare copies of the films of documentarian Les Blank, who recorded a series of award-winning documentaries about the folk music of Texas and Louisiana circa 1970. Martinez, nicknamed “El Huracan del Valle” (“the Hurricane of the Valley”), appears in Blank’s Chulas Fronteras, playing music and working at what was then his day job, keeper at the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville. (Martinez died in 1992 in San Benito, survived by his wife, Iduvina, their four daughters, and, at the time, 22 grandchildren, and 30 great-grandchildren.)

Up in a gray Tennessee winter, to see and hear Martinez playing conjunto in the vibrant sunlight of the Rio Grande Valley was almost more than my 8-year-old soul could bear. In later years, I would discover other musicians whose music would seem as indelibly Texan. Bob Wills would be one and Doug Sahm another, and the Texas Tornados supergroup, which of course included Sahm, Flaco, and Fender. Aside from Wills, the common thread was that it echoed music Martinez pioneered in the Valley, that sound that would eventually conquer so much of Texas and the world, and did as much as anything else to drag me back home to Texas for once and for all.

Maybe San Benito really is the center of the universe. In its own way, it has exerted a strong gravitational pull on me.