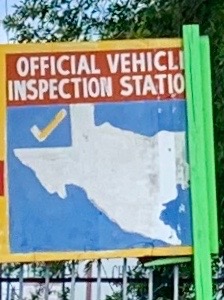

Telephone Road, Houston.

As a child, I was a collector. You name it, I hoarded it: postage stamps, coins, lead soldiers, the cards of whatever sport was in season. Toward the end of childhood, I started to “collect” bird sightings, and that hobby alone has carried on into adulthood—I am ever on the lookout for a new species to check off the list in my now nearly 40-year-old copy of National Geographic’s Field Guide to the Birds of North America.

This tendency has most recently taken shape in the practice of photography. Up until smartphones, taking pictures held little interest for me. With the rise of digital cameras and smartphones, however, my collector bent began to manifest itself in my photography.

North Shepherd Drive, Houston

Starting about 15 years ago, on a series of long walks through my hometown of Houston, I began taking pictures of abandoned shopping carts, street couches, and “muffler men,” those hand-welded sculptures of humanoids that mechanics assemble out of auto parts and put out in front of their garages. Then, as it became apparent they were an endangered species, I started shooting pay phones. But more recently, my interest has moved to a very particular but ubiquitous type of business sign: the official state of Texas inspection signboards you find at every auto garage in our state.

Earlier this year, I began to notice that while the vast majority were standardized, rote-perfect outlines of the Lone Star State, a sizable minority were not. It’s this latter category that fascinates me: these riotous folk art renditions of the outline of Texas that seem drawn from foggy memory rather than adherence to any map drawn in the past five centuries.

South Post Oak Road, Houston

If variety is the spice of life, these signs are a flavorful stew indeed, offering up coastlines either far too ragged or smooth, a smorgasbord of disproportionate Panhandles, the seeming annexations of large chunks of Arkansas and/or Louisiana, bends either much too big or too tiny out west, and down south, Rio Grande Valleys both truncated and extended and/or widened.

The signs enhance my enjoyment of the often gritty streets they inhabit and enliven the “Muffler Row” type of roadways that are their natural habitat. In short, they are a delight.

After posting a few to social media, I discovered I had a predecessor who shared this fascination, and not just any old shutterbug but the infinitely talented late Dallas Morning News photo editor Guy Reynolds.

Bellaire Boulevard, Houston

And then I despaired. Though Reynolds exclusively used a $30 Chinese Holga camera for his pictures, they absolutely blew mine out of the water. And not only were his signs captured more artfully than mine, most of the Texas signs he’d found were more exquisitely hilarious. Shots I deemed to be in my own personal hall of fame were run of the mill for him. I felt like those guys who believe they invented the guitar, only to then discover there was already a Jimi Hendrix out there expanding the frontiers of the instrument.

Eventually I gave myself a break. While my photos will never be as good as Reynolds’, I reasoned, he did have a head start. In 2013, when his obsession went public, he’d been collecting these photos for 10 years, shooting his first while pushing his son around in a stroller on Ross Avenue in Big D.

“Official signs are available from the state for a fee, but many business owners opt to paint their own,” he wrote in 2013. “These signs, with their simplistic and somewhat skewed renditions of the state’s outline, are a type of unintentional folk art.”

Westfield Drive, Aldine

Amen to that; it’s exactly how I perceive them. They’re sources of joy, not subjects for ridicule. Streets like Harry Hines Boulevard in Dallas and Houston’s Airline Drive are hardly garden spots, and there’s a beauty in anything that deviates from standardization, anything that shows the sort of human foibles a computer-generated laser-printed sign mercilessly squashes.

“Some of the efforts aren’t bad; in fact, they’re almost Texas,” Reynolds continued. And that—Almost Texas—is the title of his 2014 book, an assemblage of the best of the worst or worst of the best of the “cartographic inaccuracies” he harvested.

“Everything is a potential photo essay in my eyes,” Reynolds wrote. “Some take a few hours to complete, and some take years before coming to fruition. This one will continue as long as I keep finding signs.”

While my skills may never match those of Reynolds, close is good enough when it comes to my almost Texas.