Country road,take me home

Find desert solitude and

off-grid adventure on

Big Bend’s rugged River Road

I woke before dawn

to thunder, its hard edges softened by distance. Through the mesh canopy of my tent, I peered north at the clouds strobing like paper lanterns above Punta de la Sierra. From where I lay, near the edge of a bluff overlooking the Rio Grande, I could see Mexico in three directions, not just one.

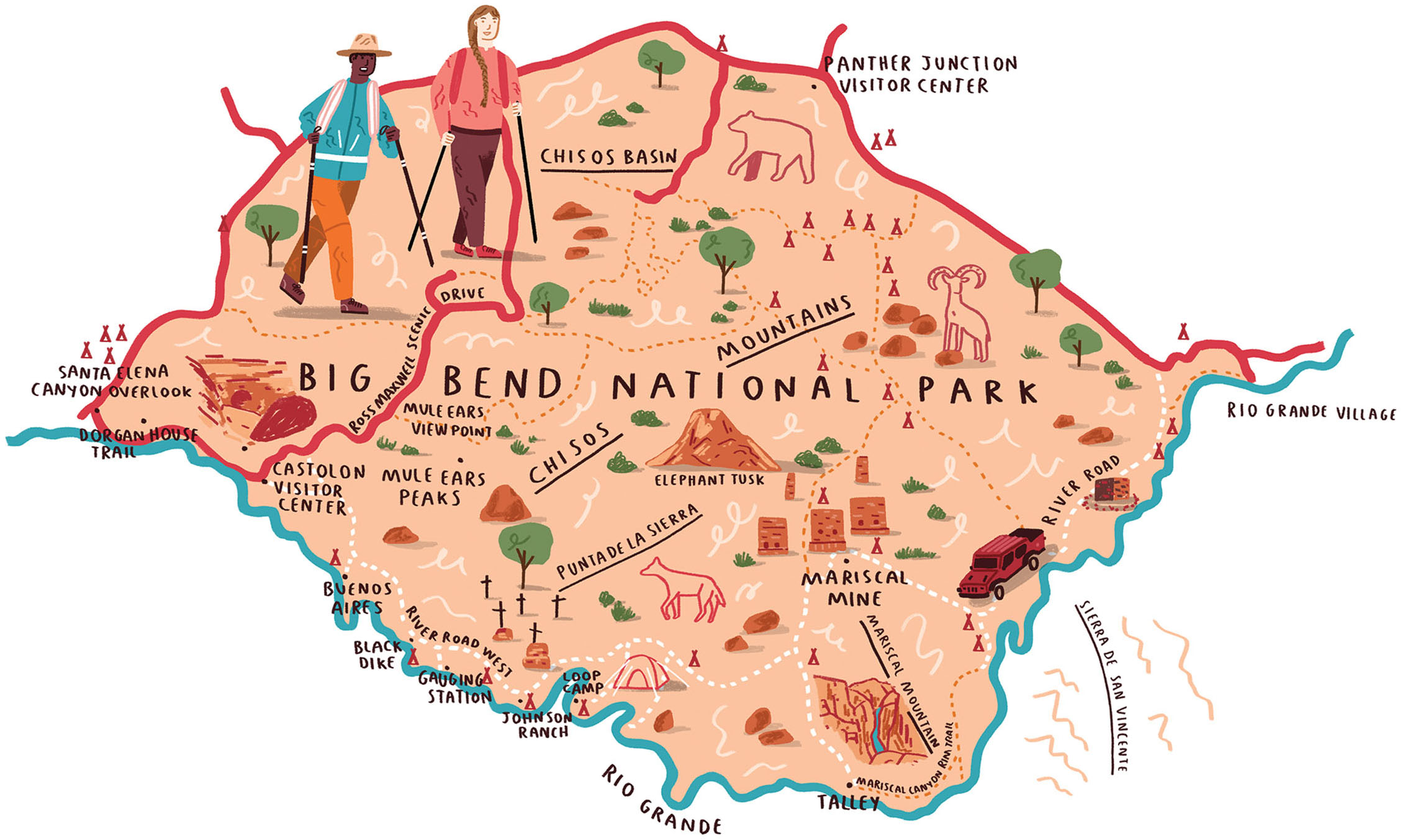

It was my second night on the legendary River Road, Big Bend National Park’s longest and least-traveled primitive auto trail. Not to be confused with Farm-to-Market Road 170—the paved highway also known as River Road that connects Presidio and Terlingua—this route is a slow-going dirt track demanding a high-clearance vehicle, often four-wheel drive. Roughly parallel to the Rio Grande, River Road appeals to a self-selecting sliver of desert travelers like myself with a desire to drop off the grid and avoid human contact for a few days.

I’d embarked on this trip with two other men—my brother-in-law, Brian Kratz, an imperturbable physical therapist from Austin; and E. Dan Klepper, a Marathon-based photographer and avowed desert rat. It was our intention to spend the better part of four days driving the trail’s entire 52-mile length. Along the way, we’d see whatever the desert offered up.

I suspected this would be my last big trip for a while. The park had always been for me a symbol of untethered young adulthood, a wilderness playground where I was free to vanish for however long I could get off work. But with my wife expecting our first child in a matter of months, I wondered how my relationship with the park would change. The same backcountry cellular dead zone that had once been liberating now made me anxious about checking in on my growing family.

Life at home might be about to change, but I took comfort in the simplicity of our River Road plan: Keep trekking along Big Bend’s southern border until we hit the pavement at the road’s western terminus, near the Castolon Historic District. We’d set out from Terlingua in a rented Jeep the day before. After 90 minutes of driving across the park, our adventure had only truly begun once smooth pavement gave way to rock and pale caliche dust at River Road’s eastern entrance, near the Hot Springs Historic District. Our vehicle was now our lifeboat, stuffed from floor to ceiling with a meticulously culled and curated supply of gear, food, and water.

Now, 30 miles into the trip, in the most remote section of the park, the troubled skies in the distance were a reminder that this was not a simple camping excursion. I’d been warned about the road’s temperamental nature. Striped by flood-prone creek beds and stretches of clay and sand, it can become a bog of impassable cake batter after a good rain. A park ranger may come along only once every few days. People have died out here after getting stuck, then attempting to hike out.

As the storm approached, Brian and I squatted in the bare dirt and struggled to guide tiny nylon loops onto the tent stakes as my rain cover popped in a veering wind. Thunder glanced off the mountains and rolled over the river valley in waves you could hear coming before their full sound arrived. Before too long, we’d need to get back on the road—so long as the rain held off. I tried to will those clouds away.

The park had always been for me a symbol

of untethered young adulthood, a wilderness playground

where I was free to vanish for however long I could get off work.

Tents at Fresno Camp

Compared to the well-worn trails of the frequently Instagrammed Chisos Mountains, the park’s southern desert sees far fewer visitors. When the Spaniards referred to the Big Bend area as “El Despoblado,” or the uninhabited land, these flat expanses of creosote brush and sun-scorched mountains were probably what they were talking about. But I’d come to love Big Bend’s brutal outback. If you open yourself to its merciless beauty, iconic sweep, and utter solitude, the place really grows on you.

In fact, the land along River Road was once anything but uninhabited. When the U.S. Geological Survey drew its first maps in 1903, the road was already there. It probably started out as a game or livestock trail, the most sensible path between mountains and to water. Over time it became a wagon trail, which eventually became a road connecting the floodplain farms, cattle ranches, fishing camps, and quicksilver mines near the river.

These far-flung settlements were virtually unknown to the outside world, but they once comprised a thriving community—just about as rugged as individualists get. This continued until the 1940s, when the national park was created and mercury prices collapsed following World War II. “These people were one-of-a-kind,” said Tom VandenBerg, the park’s chief of interpretation. “It’s natural to think nobody’s ever been out there before. But then you turn a corner, and there’s a graveyard or an adobe house melting back into the desert.”

As I saw it, this trip was about crossing a land both changed and changeless. Things certainly looked different than in olden times. The Rio Grande was bigger and wilder before upstream impoundments choked its flow. Cottonwood and willow trees lined the banks until miners cut them down to feed their operations. Grass was said to have reached a horse’s knee before cattle stripped the land bare and the topsoil eroded away.

While it may be hard to imagine any vertebrate eking out a living here, much less humans, the Chihuahuan Desert still teems in its own way. Home to hundreds of plant and animal species found nowhere else, it’s the Western Hemisphere’s most biologically diverse arid region and one of the most diverse national parks. “We’re located at about 29 degrees latitude,” VandenBerg said. “So we have a lot of Mexican species at their northern limit, and we’re at the southern limit of our northern species. The river is a corridor for all these things you normally wouldn’t see in the desert.”

“It’s natural to think that nobody

has ever been here before. But then you turn a corner,

and there’s a graveyard or an adobe house melting back into the desert.”

Photographer E. Dan Klepper cools off in the Rio Grande below Loop Camp

I felt like a kid behind the wheel of a toy, gunning the Jeep through sandy washes and easing it into deep cuts trenched by the monsoon rains. It sure beat dodging potholes in Dallas. When we stopped and ate sandwiches at noon on that first day, Brian’s eyes scanned what must have looked to him like a treeless, windswept wasteland in varying shades of brown. This was his first expedition into the backcountry of Big Bend. He laughed. “Nice vacation you got here.”

Illustration: Alex Foster

“Welcome to the desert, my friend,” I said. It’s certainly a different kind of grandeur than the Rocky Mountains or old-growth redwood forests. The desert’s allure is made of subtler stuff. I was confident that with a sharp eye—and the aid of the Road Guide to Backcountry Roads of Big Bend National Park—the parched land before us would gradually spring to life.

On the nearby desert floor, small rocks formed a circle where, as late as the 1930s, farmers drove burros around over beds of wheat, their hooves doing the threshing. In those days, the river was more accessible and easier to divert onto floodplain crops. Now the banks are often steep, held in place by impenetrable thickets of invasive river cane.

Elsewhere, the Chihuahuan Desert looked much as it always has. Delicate pastel clusters of white, pink, yellow, and purple erupted from tough-as-nails prickly pear, yucca, ocotillo, and lechuguilla. Near the tilted, dinner-plate folds of the Sierra San Vicente, we spotted a kestrel kiting from limb to limb in a mesquite tree. Roadrunners skittered ahead, like tiny vanguards, before plunging headlong back into the brush.

By the first afternoon we arrived at Mariscal Mine, an abandoned cluster of crumbling structures embedded into the trailing end of a mountain spine, nearly 20 miles from River Road’s eastern starting point. We clambered across the slopes, past monolithic condenser buildings, gated mine shafts, and the rubble of kiln bricks. For more than 40 fitful years, until 1943, this had been a cinnabar mine and mercury refinery.

The laborers, mostly Mexican nationals, had dwelled here with their families in dugouts and stacked-rock houses, laboring in inhuman conditions. Some who manned the furnaces lost their teeth, while the worst-off descended into dementia—dangers of mercury poisoning. “The vapors were incredibly toxic,” VandenBerg said.

We broke camp just to the northeast of the mine, at a site called Fresno, our tents grouped in a small clearing in the brush. Sunset saturated the deep greens of the creosote. The ocotillo, with its stems grasping at the sky like cephalopod tentacles, could have been life from another planet. Brian and Klepper huddled over their cameras, clicking away while the shadows lengthened across the desert floor.

I sat in a canvas chair, enjoying the desert silence of that first night on the road. Bats winged overhead, quietly chirping their echolocations. I wondered how long it would be before I would return here. I struggled to envision my life as a father. What would change forever and what would stay the same? Here I was, with free rein to roam the backcountry, my son’s arrival still months away, and I was already panicking. That’s the thing about the desert at night: There’s plenty of room to think.

Brian sat down next to me. He was quiet for a moment. “You ready for this?”

“Man, I don’t know. I sure hope so.”

“You are,” he said evenly. “You’re ready. You just won’t really feel that until you see him.”

Every time I’ve traveled deep enough into

the big bend backcountry, I’ve been fortunate to witness at least

one of these moments, when the hair on my arms stands on end.

A panoramic view of the Chisos Mountains from Buenos Aires campsite

Over the next few days we passed between mountains and across floodplains where the only end to the horizon was the curvature of the earth. We stopped almost as much as we drove. At one riverside stop, we explored the remains of the Elmo and Ada Johnson homestead, a ranch and trading post established in 1927. After a 1929 raid by Mexican bandits, the Johnson Ranch became the U.S. Army Air Corps’ southernmost airfield in Big Bend, ready to deploy should the unrest between government and rebel forces in northern Mexico spill over the border. Later, hunters would fly in to bag mule deer, occasionally hotdogging their single-engine craft between the eponymous peaks of Mule Ears. Little now was left aside from the ruins of a few outbuildings and the footprint of the Johnsons’ adobe house. Nearby I found a grave marked by a plaque and a loose mound of stones: “Jack Holliday: Born 1912, Drowned 1933.”

By dusk, we’d arrived at our mile 30 site, located high up on a bluff and overlooking the river. We settled into our routine, firing up propane stoves with the Jeep as a windbreak. We passed the night drinking bourbon from steel mugs and tequila from a plastic pouch, searching for constellations, and listening to the call and response of owls.

Awoken by thunder the next morning, I stood next to Brian as wind rushed up the bluff and hurtled against our bodies. The storm’s disc swept low, spanning the Sierra Quemada from Punta de la Sierra to Mule Ears Peaks. As dawn approached to our east, a sliver of clear sky beneath the clouds paled to blue, then tangerine, before spilling over the sheer wall of the Sierra del Carmen. The light crept slowly west toward the storm, until the dark clouds themselves were aflame. The volcanic mountains warmed from purple to cinnamon to terra cotta.

Every time I’ve traveled deep enough into the Big Bend backcountry, I’ve been fortunate to witness at least one of these moments, when the hair on my arms stands on end. These are the best parts—the ones that defy planning. Brian and I had already decided we’d bring our kids back here someday. There’s so much a father can get wrong, but showing your children this place can’t be one of them. We packed up the Jeep and steered west, ahead of us dusty miles still to go.

Roving River Road

To prepare for an overnight or multiday trip on River Road, visitors must reserve campsites at Big Bend National Park’s Panther Junction Visitor Center. The backcountry permits cost $10 per night and can be obtained up to 24 hours in advance, on a first-come, first-served basis. Have your campsite itinerary planned, with alternates in case some have already been reserved; there are only 18 campsites spaced out along the road’s 52 miles.

River Road East embarks from Park Route 12, about 5 miles west of Rio Grande Village and 15 miles southeast of Panther Junction. The Big Bend Natural History Association’s Road Guide to Backcountry Roads of Big Bend National Park is a helpful resource for information on sites and natural features along River Road.

High-clearance vehicles can handle some of the terrain, but four-wheel drive may be necessary for certain areas of deep sand and exposed bedrock. Be sure to check the weather beforehand. As Big Bend National Park Chief of Interpretation Tom VandenBerg put it: If it’s muddy, “it doesn’t matter if you have an Abrams tank. You wouldn’t get through the road.”

Far Flung Outdoor Center in Terlingua offers a Jeep 4×4 for rent starting at $189 a day.