Caprock Canyons State Park and Trailway lies along the western edge of the Llano Estacado. (Photo by Kenny Braun)

Some know it as the Rolling Plains. Others call it Cowboy Alley. A land of open road and enormous sky, the Big Empty lies more or less north of Abilene and east of Lubbock. Larger than some states, with a population smaller than many urban zip codes, the seldom-traveled chunk of prairie is home to red-dirt farms and huge ranches, from the Pitchfork and Matador to the Four Sixes.

“It’s a kind of place you drive through to get somewhere else,” says Reed Underwood, a native son who recommends slowing down to have a look around.

Rick Perry is from there. So was Bob Wills, the king of Western Swing. The region stretches between the Western Cross Timbers in the east, to the Caprock Escarpment in the west, and the Red River valley in the north. The Big Empty’s southern boundary is harder to define, but it’s somewhere north of the similarly named “Big Country” region around Abilene. Though definitive population counts don’t exist for the unofficial region, local sources say it’s somewhere around 20,000.

To get there from most urban centers in Texas, drive practically to the Panhandle. When you don’t see anything, stop.

Long-abandoned barns and farmhouses dotted the prairie, as did the remains of tiny ghost towns where farmers once congregated to do business, attend church, and send their children to school.

I hit the highway in late July, heading west by northwest out of Fort Worth. When the scrub forests of the Cross Timbers fell into my rearview, I ventured like some modern-day pioneer onto the boundless prairie—except that I was burning asphalt at 75 miles per hour where Comanche and bison once roamed.

This was the Big Empty. And, boy, was it empty. I sped past red dirt and green fields, rows of cotton and other crops, nary another car on the road. For a person who grew up in the shade of the Piney Woods, I find few sights quite as thrilling as the immense views of the West. Overhead, the sun shone brightly, but the highway led into the path of a silvery storm cloud that billowed above the horizon. From the solitary cloud, four or five sheets of rain fell on the grassland. The first drops hit my windshield a half-hour later. Within minutes, I’d passed right through.

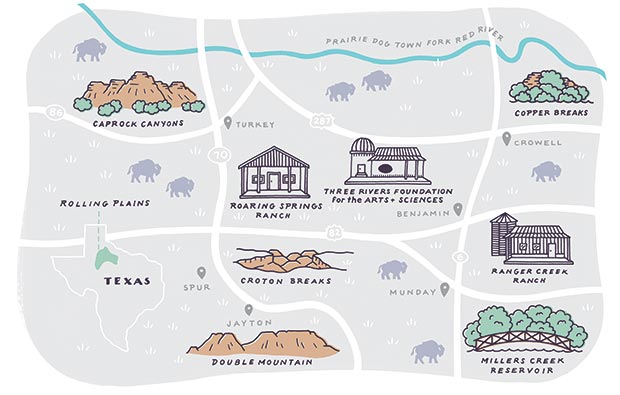

Illustration by Margaret Kimball

Long-abandoned barns and farmhouses dotted the prairie, as did the remains of tiny ghost towns where farmers once congregated to do business, attend church, and send their children to school. They reminded me of a conversation with Underwood before my trip. I had reached out to him because he recently completed a master’s thesis at the University of North Texas on the Big Empty. A native of O’Brien, population 102, where his father was the six-man football coach, Underwood says the region’s population has fallen every decade since 1930. Elsewhere, Texas is growing fast, but the populations of some of the Big Empty’s 10 or so counties have shriveled to one quarter the size of their numbers in the heyday of the early- to mid-20th century.

This largely “featureless” region has no buildings taller than two or three stories, according to Underwood. “Rather, its landscapes are by and large testaments to abandonment,” he writes in his thesis, going on to describe the “empty storefronts on quiet town squares, overgrown schoolyards made redundant through successive consolidations, tumbledown empty farmhouses melting into the red clay.” When the area’s high school seniors receive their diplomas, he adds, “most of them keep marching out of town to look for opportunity elsewhere.” Underwood has moved away from the Big Empty as well, but he is still sorting through the odd feeling of being from a place he believes to be dying.

My first afternoon in the Big Empty, I drove down the quiet highway toward the town of Goree—formerly 640 people, now 208—when a stately brick church caught my eye. Its steeple sprouted out from behind hugely overgrown shrubs. St. John Catholic Church, I later learned, was established in 1908 and served the once-bustling Bomarton community. From 598 residents shortly before World War II, the population plummeted to 15 at the turn of the millennium. In 2010, the U.S. Census didn’t even register Bomarton as a place.

Overgrown shrubbery all but obscured the front doors of the church. A handwritten sign nailed to the door read: “This was a house of God and still is.” Another note posted to a support beam just inside the empty cathedral seconded the point: “Not Abandoned.”

Moving on to Munday, which at 1,324 people is one of the area’s more sizeable towns, I checked into the American Star Inn, managed by Cindy Patchett. Her husband previously lived in Munday, and the two moved back while their children attended school. “At first the kids hated it,” she said. “Now they won’t leave. They’re raising their own children here.”

And what is there to see and do around here? “The lake,” she answered. “And… the lake.”

A cowboy rides across the open prairie 3 miles west of Benjamin. (Photo copyright Wyman Meinzer)

That weekend, some of her guests had caught a mess of catfish from nearby Millers Creek Reservoir. I hadn’t brought my fishing pole, but I did have a pair of swim trunks. About 16 miles east of town, past white rows of enormous wind turbines, the 2,212-acre lake is accessible by a maze of dirt roads through mesquite thickets that lead to free campsites along the bank.

Nobody seemed to be at the reservoir, except for two brothers-in-law named Daniel and Simon who tended a grill while their wives and a son played in the water. They offered me a sausage wrap and a grilled pork chop. Between their broken English and my broken Spanish, I learned Daniel works in the oilfield and Simon is a cotton farmer.

A breeze rippled across the blue lake. Overhead, armadas of stratocumulus marched past swirls of cirrus. The reservoir had only recently filled to capacity after the most recent drought. “Two years ago, the lake was dry,” Simon said. “The water was just 1 foot deep.”

Sleek, black cows lowed from a safe distance as I eased into the bracingly cool water. Floating on my back, I couldn’t tell which drifted faster: the clouds or me. Later, as the sun set, strobes of lightning burst far beyond the lake’s eastern shore.

In the morning, I would begin my search for a dead man.

Mammatus clouds reflect the setting sun after a storm passes over Knox County. (Photo copyright Wyman Meinzer)

The late author and Texas Christian University professor Jim Corder came up with the name for the Big Empty. A genre-defying scholar of postmodern rhetoric, Corder first used the term in print in his memoir Lost in West Texas, published in 1988 when he was 59. Corder grew up in Jayton, an hour’s drive west of Munday and 90 miles east of Lubbock. “The territory I love out there is not much chronicled,” he writes in Lost in West Texas, going on to lovingly describe geographic features of the Big Empty like Double Mountain, “blue above the broken plains surrounding them,” and the Croton Breaks, a “great empty space” of rugged badlands eroded into sharp washes. “The earth opens itself up in layers there,” he writes, “and each rock that falls after an age’s pushing from the side of a gully reveals another surprise.”

As I drove past Double Mountain, its humps seemed less blue than red and green, blotched white by gypsum, a salty mineral common to the region. To my frustration, I couldn’t catch a glimpse of the Croton Breaks from the flat prairie highway connecting Jayton and Spur. However, my map revealed evidence of the breaks via a network of riotously squiggly roads immediately to the east

The map’s little county roads seemed to pass a series of canyons with evocative names like Dark and Getaway. I had a full tank of gas, and nobody was waiting for me. Why not turn off the main highway and get lost for a while? Life is normally so busy. It felt almost luxurious to roll the windows down, smell the sweet grass, and listen to nothing but the crunch of gravel, the hum of cicadas, and the occasional rumble over cattle guards. A particularly high overlook revealed miles of rugged landscape where red canyons gashed the low green hills. The road dropped dramatically into country so eroded that it rivaled the desert floors of the Big Bend, practically halfway across Texas, for its rough beauty.

Founders of the town of Matador named it after the Matador Ranch. (Photo by Kenny Braun)

The path rose and fell as it looped around sharp turns through gullies and washes. I could have spent the day exploring these backroads, but they eventually became too rough for my crossover SUV, and so I turned around. Once when Corder was asked where he hoped to end up when he died, he responded that he would just as soon go to the Croton Breaks. As I drove out of the badlands, Corder’s wish seemed to make sense.

For those who prefer travel on pavement, you can also glimpse the Croton Breaks from the freeway just east of Dickens. The town is a half-hour’s drive north of Jayton and 20 miles south of the Roaring Springs Ranch Club, once a favorite camping spot of the Comanche. Now a private, member-owned club, Roaring Springs allows members to camp, fish, ride ATVs, and cool off where a spring-fed waterfall supplies a gloriously chilly, 3-acre swimming pool.

Continuing north through quiet country from Roaring Springs, I came to the town of Matador, named for the legendary ranch. Here, three sisters have reopened a 1914-era hotel called the Hotel Matador. “When we got it, the place was junked,” says Linda Roy, the sibling on duty the week I stopped by. “There wasn’t even a roof.” Roy and her sisters beautifully restored and elegantly furnished the brick building. The Texas lawmen-themed guest room tempted me but sunset was still a few hours away, so I drove 45 miles to Caprock Canyons State Park and Trailway.

That night, the Caprock’s dramatic bluffs glowed red as the sun fell behind them. In the morning, the park’s herd of shaggy American bison frolicked, snorted, and head-butted one another in the cool air as it blew across the badlands.

Croton Breaks’ badlands topography encompasses 250 square miles below the escarpment of the Llano Estacado. (Photo by Kenny Braun)

I had come to the western edge of the Big Empty, at the Caprock Escarpment. Instead of continuing up the scarp and onto the High Plains, I turned back. The road led to the town of Turkey, which is home to not only the historic Hotel Turkey but also an annual festival in April celebrating hometown legend Bob Wills, complete with live Western Swing music and lawnmower races.

Farther east, during a stop at Copper Breaks State Park the next morning, longtime interpretive ranger Carl Hopper encouraged me to keep an eye out for the park’s namesake mineral. “The park is plumb full of copper,” he says. Sure enough, the greenish patina of oxidized copper seemed to paint many of the loose rocks on a trail overlooking the park lake.

Copper Breaks was the first state park in Texas to earn an international dark sky rating, Hopper says, claiming that his night skies are darker than those found at the McDonald Observatory in the Davis Mountains. Taking advantage of the absence of light pollution, the nearby Three Rivers Foundation for the Arts and Sciences offers star parties once a month at its Comanche Springs Astronomy Campus west of Crowell.

After hiking the Copper Breaks trail, I had worked up an appetite. Because so few people live in the Big Empty, restaurants options are limited. Luckily, I came across the Dairy Bar in Crowell. Jeff Christopher and his wife, Karen Christopher, have owned the unassuming roadside joint for 17 years. While they have no idea how old it is, they do know it was moved to its current location in the early 1960s. The Dairy Bar’s burger hit the spot. “They aren’t healthy,” Jeff says. “A good, old-fashioned greasy burger is what I do.”

The following morning, in the Vera community 40 miles southeast of Crowell, Ranell Scott and I loaded into her white pickup truck and drove across land that has been in her family for more than 100 years. Scott runs Ranger Creek Ranch, a cattle operation and hunting lodge with several guest houses.

When Scott stopped to open a metal gate, two jackrabbits fell in with a muster of turkeys and bounded across an open field. A family of wild hogs rooted nearby. Quail waddled in front of Scott’s truck, and roadrunners sprinted among the mesquite. The ranch is also on the migration path of Monarch butterflies, she says.

“The earth opens itself up in layers there,” he writes, “and each rock that falls after an age’s pushing from the side of a gully reveals another surprise.”

As Scott drove, it became apparent that we had reached the edge of a small plateau. Rolling ranchland spread for miles and miles. Scott pointed out the property line she shares with the approximately 535,000-acre Waggoner Ranch, the largest ranch under one fence in Texas. The view would have been majestic right before twilight.

“West Texas sunsets are gorgeous,” Scott says. “Nothing like ’em. And you can actually see them! We don’t have all the big trees in the way as in other parts of Texas.”

The Big Empty seemed anything but empty. So why do so few people know about it?

Wyman Meinzer has an idea. Raised a cowboy on a Big Empty ranch, he spent a few years trapping furs in the area and is now the official photographer of the state of Texas. He has taken photographs throughout the state, but his primary subject—his life’s work—is documenting the Big Empty. He captures images of cowboys and critters, scalded river breaks, and endless sunrises.

“This is a land that you have to become a participant in,” he says. “It’s not going to jump up and hit you in the face. You have to become part of it. You have to stop, look and see, and imagine.”

Fifty miles southwest of Meinzer’s home in Benjamin, Double Mountain rises from the broken prairie.

On cold and still mornings, Meinzer says he can see the Doubles in the distance. Side by side, they seem to float in the sky. And there’s a road, little traveled, leading toward them.

For visitor information, call Caprock Canyons State Park at 806-455-1492; and Copper Breaks State Park at 940-839-4331. For reservations, call American Star Inn at 940-422-5542; Roaring Springs Ranch Club at 806-348-7292; and Hotel Matador at 806-347-2939.

Kilgore native Wes Ferguson is author of The Blanco River and Running the River: Secrets of the Sabine.