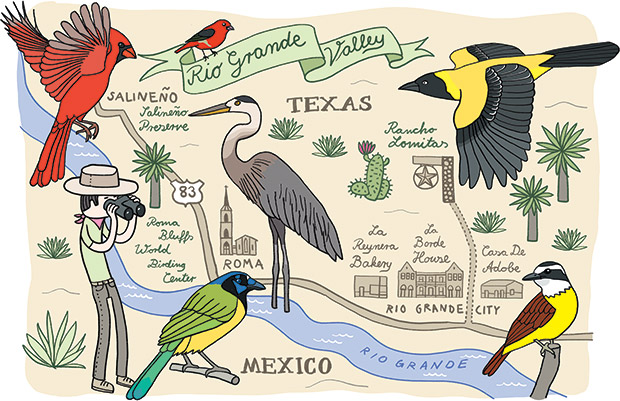

(Illustration by QuickHoney)

When nature enthusiasts think of the Rio Grande Valley, they most often picture the glimmering resacas and moss-hung forests of destinations like the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge. But venturing farther upriver, away from the large cities and the tropical influence of the Gulf Coast, one finds a strikingly different landscape of rolling ranchland, sheer bluffs, and Old West frontier towns. Not long ago, my wife, Laura, and I headed west from our home in McAllen to explore the natural offerings of Starr County. We hoped to find not only scenic vistas of starkly beautiful country but also bird and plant species that can’t be found anywhere else in the United States.

Starr County Birding

For more on Starr County birding, check out Rancho Lomitas, Roma Bluffs World Birding Center, and Salineño Preserve at 956/784-7575.

As a high school science teacher, Laura was especially looking forward to the first stop on our itinerary, Rancho Lomitas Native Plant Nursery, a 260-acre nursery and nature preserve whose owner, Benito Treviño, is a pioneer in the field of ethnobotany—the study of how humans use plants for food, medicine, and rituals. First, though, we had to get there. The ranch is 10 miles north of Rio Grande City, and no street signs marked our path through winding gravel roads. Luckily, Benito had given us superb directions, but even so, our arrival at the wrought-iron gate—just where he’d said it would be—felt like a small miracle.

Birding at Salineno Preserve.

The instant we stepped out of the car, a symphony of birdsong filled the air, and we knew the drive was worth it. A brilliantly colored scarlet tanager sang in a mesquite branch, while a flock of rare scaled quails scurried in the underbrush, their namesake “scales” glittering like chainmail. Closer to the main house, in a nectar-rich garden shaded by Texas ebonies, we found magnificent green jays feasting on oranges along with the black-headed Audubon’s oriole, another of the uncommon birds that calls the ranch home.

We caught up with Benito, instantly recognizable by his thick mustache and the bag of seeds in his hand, in his plant nursery. Twenty years ago, he started Rancho Lomitas as part of an effort to reforest some of the Valley’s native habitat, 95 percent of which has been lost to agriculture and development. The bag he was holding, he explained, contained seeds of the Walker’s Manioc plant, a threatened South Texas native with a fleur-de-lis-shaped leaf. Now, he was planting the seeds in his nursery in the hopes of someday restoring the population in the wild. Nearby, he showed us an endangered Star Cactus. The name comes from its yellow flower, but coincidentally Starr County is the only place in the United States you can find it. “These are my babies,” he told us.

When Benito was a child growing up in Starr County, his father and grandfather passed along botanical traditions that date back to cattle-driving vaqueros and indigenous Coahuiltecan hunter-gatherers. “Much of that knowledge is being lost, or already has been,” he said. On an impromptu tour of the ranch, we discovered edible and medicinal plants around every corner, including the strawberry cactus, whose fruits actually taste like strawberries. Benito also showed us a Spanish dagger yucca plant with a stalk that can be grilled like asparagus, leaves that can be woven into hammocks, and roots that can be turned into soap. “With that plant,” he explained, “you can have your breakfast in the morning, a place to rest in the afternoon, and your bath at night.”

Rancho Lomitas is also home to four furnished vacation rentals, an RV park, and campsites, but we had already made lodging reservations in Rio Grande City, so as the sun sank low in the sky, we said goodbye to Benito and drove to La Borde House, our hotel in the heart of historic downtown. One of the oldest cities in the Valley, Rio Grande City was originally part of a Spanish land grant in 1767. By the time the hotel was built in 1899, the city was a bustling port for steamboats that navigated the Rio Grande bound for New Orleans. Today, the Starr County Historical Foundation runs the hotel, which has themed rooms decorated with authentic period furniture. When we arrived at the Audubon Room and saw the fireplace adorned with tiles painted with the likenesses of green jays, we knew we’d made the right selection for the night.

But first there was the matter of food. We strolled to Casa de Adobe, a steakhouse and bar whose main dining room is in a historic home that really is built of mud and straw. We admired the original mesquite woodwork inlaid with turquoise and ordered a meal fit for two hungry vaqueros after a day on the trail—the parrillada, a sizzling assortment of beef and chicken fajita, sausage, and grilled vegetables, served in a cast-iron skillet with homemade tortillas.

Pan dulce at La Reynera Bakery.

The next morning, we woke up before dawn, knowing that the early bird gets the—well, the birds. We swung by La Reynera Bakery for coffee and fresh pan dulce, and headed out in the direction of the Salineño Preserve, a famed site in birding circles. Along the way, we stopped at the Roma Bluffs World Birding Center—part of a network of nine different Valley birding sites collaboratively run by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and local communities. The center offers exhibits on the area’s natural and cultural history, as well as a dramatic vista from a bluff overlooking the winding Rio Grande. The volunteers at the center also gave us a hand-drawn map to Salineño, located 25 miles west of Rio Grande City, for which we were most grateful. Although I’d been once before, I knew that part of its appeal lay in its location off the beaten track.

We arrived at a parking area in sight of the river and walked a well-marked path through the mesquite for a few dozen yards. Then, we turned a corner, and Laura audibly gasped. It was her first visit, and though I’d tried my best to describe this place, words couldn’t convey the kaleidoscope of color and motion before us. We saw dozens and dozens of orioles, green jays, cardinals, kiskadees, and woodpeckers—along with many other species—flitting from branch to branch, some so close we could have touched them.

In the early 1980s, caretakers Lois Hughes and Merle Ihne explained, visiting RVers began feeding the birds here with a homemade mixture of peanut butter, cornmeal, and lard. Later, owners Gale and Pat DeWind gifted the property to the Valley Land Fund, a nonprofit that partners with the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge to protect the land for birds and people alike. “Generation after generation of birds have known that when their natural food source dwindles in the wintertime, they can come here to help tide them over until the spring comes,” Lois explained. All this attention, coupled with the spot’s idyllic location at a bend in the river, has meant more species of birds in one place than I’ve ever seen, anywhere.

A birding tour group arrived amid a rapid flutter of photo lenses, the expert birders no less amazed by the winged spectacle than we were. Joining us in a line of white plastic chairs in the shade of Lois and Merle’s RV, the tour leader happily reported sightings of white-collared seedeaters and red-billed pigeons down at the river’s edge. After another half-hour of birding and chatting, Laura and I added our names to the thousands already in the guest book and followed in the footsteps of the tour group down to the water’s edge. Watching the river gently glide past, we were content with a sighting of a great blue heron and the greatest discovery of our weekend getaway: a tranquil moment together.