Century Club

Camp Rio VistaIngram

These Lone Star icons have withstood the test of time, welcoming visitors to step into the past

Photo courtesy Camp Rio Vista (left); Kenny Braun (right)

Texas is a relatively young state. In 1836, when the first wave of settlers gained independence from Mexico and established the Republic of Texas, America’s East Coast colonies had already been populated for more than 200 years. Texas was forced to grow up quickly as it faced countless challenges—from the Civil War of the 1860s, to the Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the 1930s, to the more recent trials of the COVID-19 pandemic and Winter Storm Uri. But Texans have stood strong, proving both adaptable and innovative. As we reflect on Texas’ resilience, we’re shining a spotlight on locales that have been around for at least 100 years, such as Pig Stand in San Antonio, America’s first drive-in restaurant chain; and the Majestic Theatre in Dallas, which played host to jazz great Duke Ellington. These places aren’t relegated to black-and-white photos or historical markers—they’re still open and operating today. Visiting these century-club institutions inspires appreciation for Texas’ past and the people who preserve these treasures for Texas’ future.

The Majestic Theatre

Over the last 100 years, the Majestic Theatre has hosted performances by Harry Houdini, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Conan O’Brien, and the Moscow Ballet. While businesses have come and gone in downtown Dallas, “the Majestic has been there all along,” says Jennifer Scripps, director of the Office of Arts and Culture Dallas, the organization that runs the theater.

Karl Hoblitzelle opened the opulent 1,700-seat theater on April 11, 1921, as the flagship for his Interstate Theatre company, a chain showcasing vaudeville acts and silent films. The marble floors, glittering chandeliers, red velvet seats, and air conditioning (a luxury for most Texans at the time) attracted white-gloved visitors for decades. It later became a “movie palace” that showed some of Hollywood’s biggest films, like John Wayne’s Hatari! and The Great Escape with Steve McQueen.

“The Majestic exemplifies where Dallas came from and where it is today,” Scripps says. As neighborhood movie theaters became more common, and downtown’s once-bustling theater scene went dark, the Majestic closed its doors in 1973 after a showing of the James Bond film Live and Let Die. In 1976, The Hoblitzelle Foundation gifted the theater to the city of Dallas, with the caveat that it would restore the historic venue. The marquee lit up again in 1983, when the doors reopened for a gala headlined by Liza Minnelli. The Dallas Black Dance Theatre became the first resident company at the theater in 1984, and has performed there more than 500 times. Many centennial performances and celebrations were postponed last spring, but the theater plans to celebrate its anniversary throughout 2022 with events and concerts. —Dina Gachman

1925 Elm St., Dallas. 214-670-3687; majestic.dallasculture.org

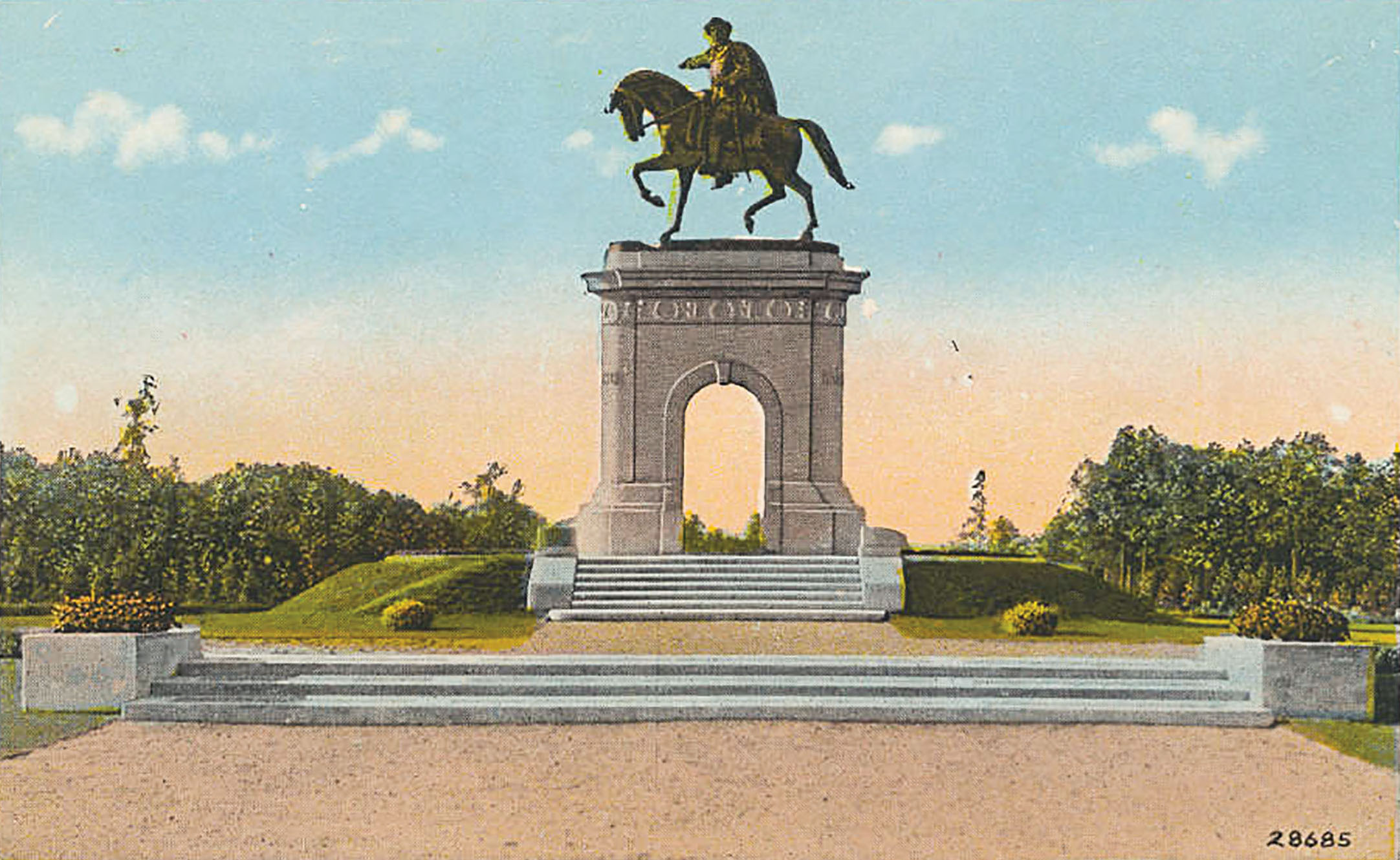

Hermann Park

The early months of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted many Houstonians to rediscover Hermann Park, the crown jewel of the city’s park system. The 445-acre public space, which borders the Museum District, the Texas Medical Center, and Rice University, provided an outdoor refuge in the middle of America’s fourth largest city. “Everybody was so stressed, so people appreciated the chance to stroll someplace that was beautiful and calm, where it was safe to let their kids run around,” says Doreen Stoller, president of the Hermann Park Conservancy, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the park. “We got so many thank-you notes from visitors.”

The park was founded in 1914, with a gift of land to the city of Houston by real estate investor and industrialist George H. Hermann. Designed by landscape architects Hare and Hare, the park took shape in phases—it now includes a zoo, an 18-hole golf course, an outdoor amphitheater, a Japanese garden, an artificial lake, and a miniature train that remains the hottest ticket in town for children. The conservancy is always adding new features, with plans currently underway for a dog park and a newly landscaped entrance from the medical center. As one of the oldest public parks in Texas enters its second century, the verdant oasis remains at the heart of Houston’s civic life. —Michael Hardy

6001 Fannin St., Houston. 832-395-7100; hermannpark.org

Old Spanish Trail Restaurant

Though Brackettville’s Alamo replica from John Wayne’s 1960 film The Alamo is crumbling into ruins, the spirit of the Duke lives on at Old Spanish Trail Restaurant two hours east of Brackettville in downtown Bandera.

A trophy elk presides over a bar lined with saddle stools in O.S.T.’s older half—a former grocery that opened in 1921. (Though O.S.T. resembles a saloon, to imbibe you must BYOB.) Later, the owners expanded into the former horse corral next door, parked a chuckwagon along one wall to serve as a buffet and salad bar, and festooned the walls with posters chronicling Wayne’s long career, focusing, naturally, on the Westerns, and of course The Alamo.

Fare here is down-home Texas-style grub done to perfection and served with a smile. As befits the world’s Cowboy Capital, the beef dishes—chicken-fried steak, burgers and patty melts, and cheese enchiladas bathed in house-made chili—rule. Try to save room for owner Gwen Janes’ chocolate fudge cake or blueberry buttermilk pie—it’s “what dreams are made of,” the menu aptly proclaims.

“I have seen many restaurants come and go trying to be the next best thing, but I have found that staying the course and changing up our menu a little is what keeps customers coming back,” Janes says. “Being good to my employees is why some have been here for 20 and 30 years. They do become a part of your family.”

After 43 years at the helm, Janes is selling the restaurant. One bite of those enchiladas, and you might be inspired to buy this shrine to Western dining. —John Nova Lomax

311 Main St., Bandera. 830-796-3836; ostbandera.com

Hruska’s

Located almost exactly halfway between Houston and Austin, on State Highway 71 in Ellinger, Hruska’s is one of the state’s most beloved highway stops. Here, weary travelers can fill their fuel tanks, empty their bladders, do some shopping, and even sit down for a hamburger at one of the half-dozen dining tables. But the family-owned store is best known for its house-made Czech pastries—both kolaches (filled with fruit, cream cheese, and/or poppy seed) and klobasniky (filled with sausage, cheese, and/or jalapeños). The kolaches alone come in 16 varieties, many of which sell out by early afternoon.

The F.J. Hruska General Merchandise Store opened on Main Street in downtown Ellinger in 1912, with owner Frank J. Hruska selling everything from groceries to furniture; he even provided local ambulance and undertaking services. In 1952, Frank’s son and daughter-in-law opened a separate service station on SH 71, eventually consolidating the service station and general store into the Hruska’s of today. The kolaches were introduced in 1962 by local Czech baker Adolphine Krenek, who made the pastries from her own recipe, which Hruska’s still uses. —MH

109 W. SH 71, Ellinger. 979-378-2333; hruskas-bakery.com

Don’t Touch That Dial

In addition to the good that firefighters do daily—like putting out flames and saving people’s lives—we can also credit them as the original Texas disc jockeys. The first radio station in Texas—the second in the country after KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—was WRR, owned by the city of Dallas and licensed in August 1921. It was created so dispatchers could communicate with police and firefighters in the field from the second floor of downtown’s Central Fire Station. To ensure continuity of connection during downtime, the blaze busters would tell jokes and stories, read from the newspaper, and play records.

This new form of entertainment cost the city $250 for a radio transmitter, which was built by a pair of Western Union telegraph experts in conjunction with Henry “Dad” Garrett, a public safety official who designed Dallas’ first traffic lights.

In 1926, WRR started selling advertising slots to pay for upgraded equipment and adapted a programming mix of music and news to be in line with other commercial radio stations. By 1931, the Dallas police and fire departments had their own wireless transmitters, but WRR still supplied and maintained all radio equipment for the city until 1969. The station, which has never used taxpayer money, was especially profitable from 1946 through 1968, when the advent of television demanded radio become more engaging.

WRR added FM station 101.1 in 1948, which is now a classical music station, still owned by the city, operating out of a building at Fair Park. The original AM station—sold to a private company in 1977—has become KTCK, “The Ticket,” a multiyear honoree as the best sports station in America by the National Association of Broadcasters.

“WRR is a very special place with so much history,” general manager Mike Oakes says. “We don’t dispatch the fire department any longer but having been a classical music station for 57 years, our commitment of service continues.” Until COVID, WRR aired Dallas City Council meetings every other Wednesday. But due to bad audio from online meetings, the station best serves the community these days as a valued source of local arts information.

—Michael Corcoran

Pig Stand

It’s hard to miss the pink pig sign high atop a mint-and-fuchsia pole, rising high over Broadway, in the shadows of downtown San Antonio. And the old-school coffee shop script in neon over the front door proves irresistible, too. Both promise a trip to yesteryear, as the Pig Stand—America’s first drive-in restaurant chain—seems little changed in many decades.

The Pig Stand chain’s last remaining location in San Antonio was one of dozens opened quickly after the original restaurant debuted in Dallas in 1921, serving sandwiches, breakfast, and burgers. Best of all, this Pig Stand—out of the 130 that once stood from coast to coast—also delivers food and mood from a bygone era. The car-hop service was terminated decades ago, but guests nostalgic for a different time can find comfort in the red vinyl booths that feature individual mini-jukeboxes with tunes by Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Willie Nelson, and Frank Sinatra. Handmade chocolate malts and root beer floats (both garnished with whipped cream and cherries) are just the beginning; chicken-fried steak sandwiches with big, crunchy onion rings and the signature pig sandwich—tender sliced smoked pork slathered in barbecue sauce—make for satisfying meals.

You’ll want to linger to inspect the hundreds of pink pig figurines, all gifts from loyal customers over the past century. “All the pigs have their own stories, some of them very sweet,” says owner Mary Ann Hill, who began her tenure as a server in 1967 and eventually bought the business out of bankruptcy with an angel investor in 2007. Even as development encroaches on Pig Stand’s last location, Hill hopes the landmark will hold on. “San Antonio’s faithful customers keep us going,” she says. “I always tell people: We own the business but not the property. If you see me dragging this building down the road, you’ll know we’re moving.” —June Naylor

1508 Broadway St., San Antonio. 210-222-9923

Camp Rio Vista

When Camp Rio Vista opened in 1921 as a Hill Country summer camp for boys, the inaugural activities included reading books in the camp library, listening to visitor talks on character development, and taking riverside hikes. A century later, the diversions are slightly more modern. But the oldest summer camp in Texas still maintains its charm against the backdrop of the Guadalupe River.

Camp Rio Vista was the brainchild of former Houston YMCA CEO Herbert Crate, who bought 1,000 acres of riverfront property between Hunt and Ingram. A dining hall, which is currently the oldest building on the grounds, came along in 1927. In 1936, Crate sold the camp to George and Carlotta Broun, a couple from Kerrville who ran it as a private family camp while rebuilding the still-standing cabins. The Brouns welcomed the public back to the site in the early 1940s, even running the camp in 1941 despite a lack of young men to serve as counselors due to World War II. During this era, activities included motorboating, horseback riding, riflery, archery, hiking, arts and crafts, and the start of camp traditions such as the Mystic Dance. The last was held with the girls from nearby Camp Mystic, which was established in 1926.

In 1977, Camp Rio Vista landed in the hands of Carl and Diane Hawkins, who had previously owned nearby Heart O’ the Hills Camp for girls. They continue to run Rio Vista today as an all-boys camp and started Camp Sierra Vista for girls on the same property. “We have always done summer camp,” says part-owner Justin Hawkins, Carl and Diane’s grandson. “And we love it. We think summer camp nowadays is probably more important than ever because camp is one of the last places kids can just come and be kids.” —Jacqueline Knox

175 Rio Vista Road South, Ingram. 830-367-5353; vistacamps.com

Dickies

Nearly 100 years ago, when hat salesman E.E. “Colonel” Dickie went into the workwear trade making denim overalls in Fort Worth, he probably didn’t envision the company’s attire becoming a fashion staple in the hip-hop world and beyond. But that indeed is what Williamson-Dickie Manufacturing—cofounded by Dickie’s cousin C.N. Williamson—accomplished.

Over the course of its existence, Dickies has never been favored by one group or another, says Rachel Courts, Dickies’ director of global communications.

“Our brand easily transcends all decades, societal dress codes, and demographics,” she says. “Our workwear allows [people to] express themselves.”

During the Great Depression, as Texas’ economy shifted from agriculture to oil, Dickies became the top choice in pants, shirts, and coveralls for generations of tool pushers, roustabouts, and roughnecks. World War II brought more boom times. The U.S. government contracted with the company for military uniforms by the freighter-load, with the khaki “chino” pants winning enduring popularity not just with soldiers but with suburban dads, golfers, and college professors.

As the Texas oil industry went global, Texan oil field workers brought steamer trunks full of Dickies with them to places like Venezuela and the Middle East, igniting the company’s expansion. As with Levi’s a few decades earlier, the late ’70s and early ’80s saw this reliable line of work clothes become adopted as streetwear. Beginning with Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles, Dickies caught on with West Coast rappers like NWA and Texas group UGK, whose late member Pimp C once dedicated a song to the brand, rapping, “Got red Dickies, white Dickies, orange Dickies too / And I even got the blue for when I represent for Screw.” —JNL

Dickie’s Flagship, 521 W. Vickery Blvd., Fort Worth. dickies.com

The Gardner Hotel

The Gardner Hotel, turning 100 in May 2022, is El Paso’s oldest continually operating hotel. It has been frequented by the likes of gangster John Dillinger—who checked in under the alias John D. Ball—and author Cormac McCarthy. “He mentions the hotel in a lot of his books,” general manager Stephanie Nebhan says.

Seemingly everywhere you look inside the hotel built by Preston E. Gardner on the corner of Franklin Avenue and Stanton Street, hints of decades past abound. There’s an old yet nonoperational phone booth, actual keys (instead of cards) to get into the 46 rooms, and the original marble stairway with wooden handrails. The hotel also has four hostel rooms, each with four beds.

“We’ve done a lot to keep it original,” Nebhan says. “But we’ve done upgrades too. Before, they didn’t have showers in any of the rooms, so we’ve installed showers.”

The Gardner’s private rooms start at $69.99 a night and are appointed with original antique furniture and a vintage-style bathroom from the hotel’s early years. It also has renovated rooms that include flat-screen televisions. The hostel section, starting at $24.99 a night, is pared down with bunk beds and a communal kitchen.

Since the hotel features a lot of touches and décor from its early days, it’s easy to imagine Dillinger and his cronies laying low there during the Great Depression. He became known as Public Enemy No. 1 during his stay at the Gardner. —Roberto José Andrade Franco

311 E. Franklin Ave., El Paso. 915-532-3661; gardnerhotel.com

Out of the Park

As an adolescent, Andrew “Rube” Foster was singularly focused on baseball and so confident in his talented right arm that he joined the Waco Yellow Jackets semipro team in 1897 after turning 18. Over the next three decades, the Calvert native would have no occupation or interests outside of baseball as he became a dominant pitcher, an innovative manager, a shrewd team owner, and a visionary league president who would be remembered as the “Father of Black Baseball.”

“I am partial to baseball, have followed it since a child and have never been identified with any other [pursuit],” Foster said in a 1924 interview with the Chicago Defender. “I have found the one thing that gives me more pleasure than anything else.”

Baseball also afforded him historic levels of success. In a 20-year span from 1897 to 1917, Foster was the best pitcher among Black baseball’s independent barnstormers and then league-affiliated teams. He tossed eight no-hitters. When he bested Hall of Fame Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Rube Waddell in a 1902 exhibition game, Foster was tabbed “the Colored Rube Waddell,” which he proudly acknowledged in Robert Cottrell’s book The Best Pitcher in Baseball: The Life of Rube Foster, Negro League Giant.

In that same year, Foster won 44 games in a row for the Chicago Union Giants. In 1910, as a player-manager with the Chicago American Giants, he led the team to an astonishing 128-6 record.

Foster’s legend was solidified in 1920 when he stepped up as the guiding and domineering force in establishing and running the eight-team Negro National League, which prospered throughout the decade though he never reached his goal of integrating Major League Baseball.

“The Negro National League was the first all-Black league to survive a full season, and all the credit goes to Rube Foster,” says Larry Lester, author of Rube Foster in His Time. “He would say, ‘I’m going to put a team on the field that white Americans cannot ignore. They will have to accept us as equals, as a professional team, and eventually as a league.’”

Foster died from a heart attack on Dec. 9, 1930, at age 51. He has been inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame, the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame. A marker honoring Foster is located at Calvert’s Payne-Kemp Park. —Michael Hurd