Keith Carter has a problem. He’s one of the world’s great photographers, with a legendary sense for the mystery in the mundane. But right now he’s at home in Beaumont, and his longtime assistant, Cathy Spence, is calling for help from a side door.

“She’s out there putting textures on a dead snapping turtle, and it’s not going too well,” he says.

There’s usually one critter or another to fuss with in Carter’s corner of Southeast Texas, a place he likes so much because it’s “flat, tangled, wet, deeply green, and full of really good storytellers.” He’s also a fan of possums and poetry. For his photographs, Carter prefers the arcane, the imperfect, the muddy, and what he calls the gumbo culture of Beaumont—a blend of “white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, Hispanic imagination, African American experience, Vietnamese industry, rednecks, and peckerwoods,” all of them inspiring in their own way.

Photo: O. Rufus Lovett

Carter excuses himself only to return a moment later, the fate of the snapping turtle as mysterious as so much of his work. He slides into an antique armchair bathed in window light as Mexican ballads play through his old, stone house in the Oaks Historic District, a Southern Gothic neighborhood of sprawling trees and creeping vines in this riverport city of nearly 120,000. Rising from the coastal marshes east of Houston, Beaumont is probably best known for its petrochemical industry and the Spindletop gusher that blew in Texas’ first oil boom in 1901—not so much the international art scene. But Carter has lived here since he was 5 years old. He travels widely and could live anywhere, but he always comes back. Now 70, a petite man with an urbane air and ironic wit, Carter is enjoying a new round of appreciation: A half-century retrospective of his most enduring images is making the gallery rounds, and this month he published his 12th book, Keith Carter: Fifty Years.

Where to meet Keith Carter and see his work

More than 100 of Carter’s images are on display at The Wittliff, which is on the seventh floor of the Alkek Library at Texas State University. Other exhibitions of Carter’s work include the PDNB Gallery in Dallas in March and the Lamar University’s Dishman Art Museum in Beaumont later in 2019.

Carter maintains a fairly low profile in Beaumont. Although he has taught for two decades at Lamar University, where six of his images are on permanent display in an honors college building, his name drew blank or uncertain stares from a hotel concierge, a few restaurant servers, a bartender, and a karaoke singer when I visited last fall. But Carter is revered by photographers and art collectors worldwide. His work has been shown in more than 100 solo exhibitions in 13 countries, and it resides in permanent collections from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. In 2009, he was awarded the Texas Medal of Arts.

“He’s just a true artist,” says writer and collector Bill Wittliff, a close friend. “Keith is not just taking pictures. He’s making art, and that’s different. You look at his images, and they’re absolutely magical.” Roy Flukinger, a curator emeritus at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, describes Carter as “one of the most original photographers in Texas to have come our way in the last couple of generations.” And to O. Rufus Lovett, an East Texas photographer and educator, Carter is a pioneer: “Keith really paved the way for a lot of us to go about a more personal approach.”

Surprisingly, Carter says he did not shoot a single picture until he was 19, despite growing up around photography. His mom, Jane Carter, made a living as a portrait photographer in Beaumont after his father deserted their family when he was 6. “Things were unstable,” Carter recalls. “My mom really worked hard, and I would hang out at the studio, just because that’s where you went after school.” Carter never thought to take his own pictures. He was a “shallow, unfocused youth,” too busy surfing and playing guitar or reading. His life changed when he was about to graduate with a business degree from Lamar. He borrowed his mom’s camera one afternoon and snapped a few photos of men fishing from the banks of the Neches River, then paid to have the film developed at a drugstore. “Honey, you have a good sense of light,” Jane told him when she saw the results. “You have a good eye.”

“Being in a small town, there were very few people to talk to. I lived to find somebody new, whose work made me think differently.”

With his mom’s encouragement, he found focus, and he borrowed photography books from his neighbor, a sculptor and mentor named David Cargill. “Being in a small town, there were very few people to talk to,” Carter says. “Any time you saw a small exhibition, or you saw somebody’s work that was so much better than yours, it was just like an epiphany. I lived to find somebody new, whose work made me think differently.” At one point he sold his motorcycle to buy a Greyhound bus ticket to New York City, where he spent three weeks poring over the works of masters at the Museum of Modern Art, an experience he now describes as his graduate education.

Carter assisted his mother for a couple of years. He married Patricia Staton, a well-read, no-nonsense widow who’d grown up in Trinity, and they opened a studio. Pat ran the business, and Carter became a workaday portrait photographer like his mom. But he always had an itch to do something more. Then he attended a public talk in Galveston by Horton Foote, the screenwriter for To Kill a Mockingbird and Tender Mercies. Foote advised his audience to “belong to a place”—to make art from what you know. Carter bolted upright in his seat. “I was on fire,” he recalls. “I thought, I’m going to go home, and I’m going to photograph these few counties that nobody pays any attention to. I’m going to learn the folklore. I’m going to learn the animals. … I’m going to photograph all of the music in the churches, and everything that’s in this rural culture because that’s what I know.”

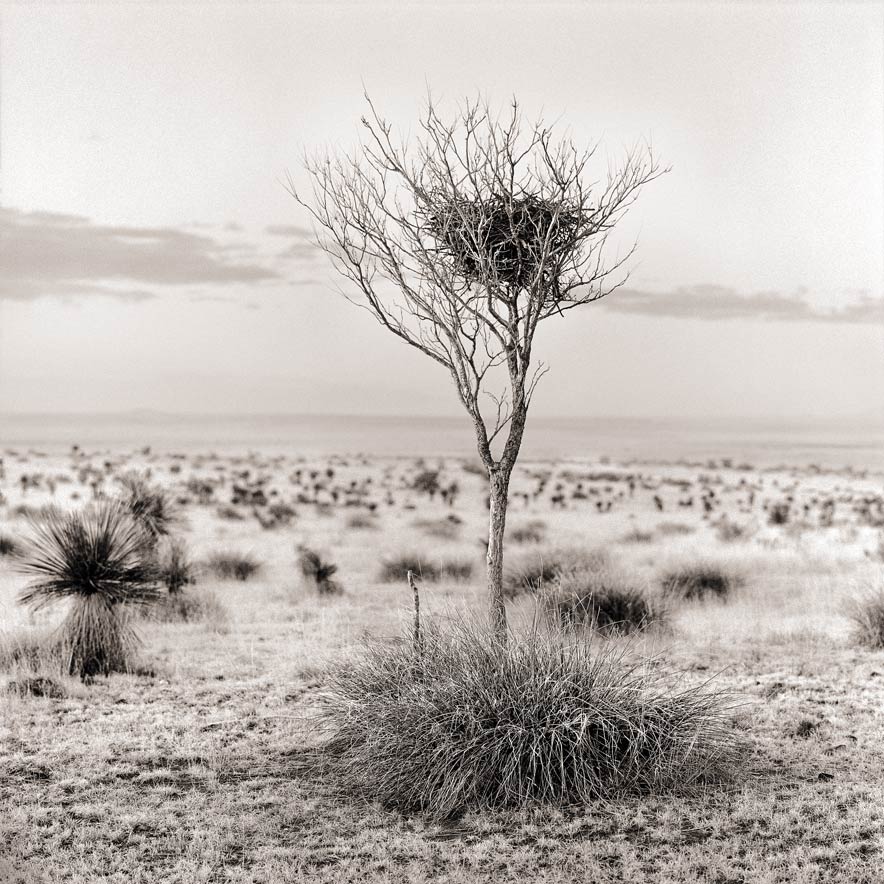

Carter had always felt most comfortable in rural places. To celebrate their 10th wedding anniversary, he and Pat decided to travel to 100 small Texas towns with interesting or odd names, like Pep and Birthright. Carter made a photograph at each stop. The resulting book, From Uncertain to Blue in 1988, put him on the map. The Los Angeles Times declared him the “poet of the ordinary” for his quietly off-kilter images of children, animals, and timeless rural scenes. The “ordinary” description has followed Carter ever since.

Commissioned work began to pour in. But Carter pivoted, the result of dumb luck: Around dusk one evening in 1992, he was trying to photograph two little boys catching fireflies in a jar. The boys wouldn’t hold still long enough for him to make a decent picture, and when he developed the negatives, they were out of focus. Carter was depressed. Pat told him to print the picture anyway; then she told him to print it bigger. It became Carter’s most famous image, Fireflies.

“It’s the blur that made the whole thing work, that passage of time,” Carter says. “It was no longer specific in detail. It was about open-ended narratives. It changed my whole life, but I didn’t see it at first. I thought it was a mistake. It was Pat who saw it.”

“I was trying hard to destroy what I loved, what I thought was precious, in the hopes of bringing forth something new.”

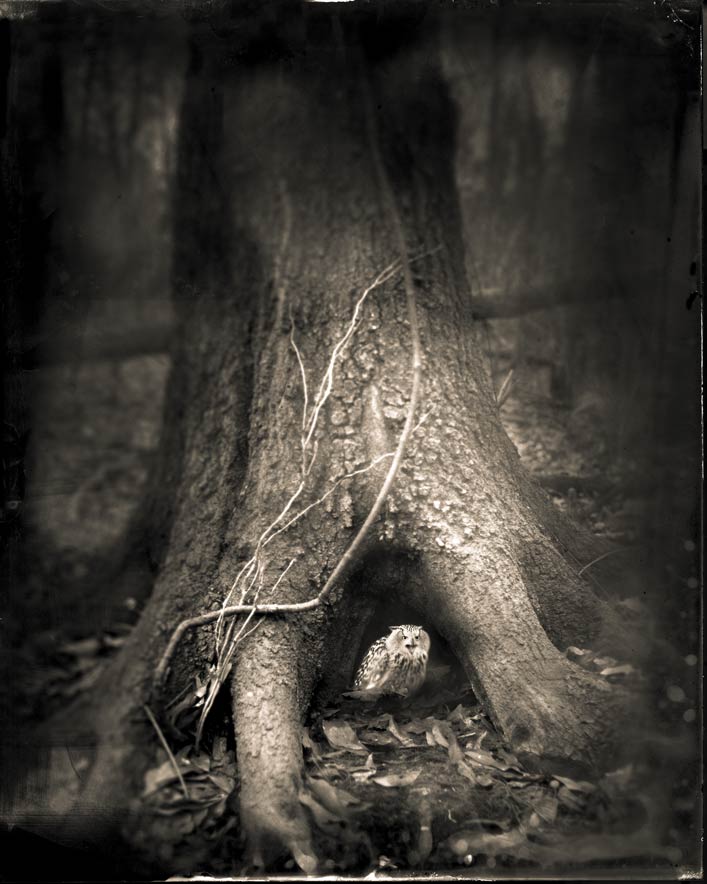

His work grew more personal, more haunting. Experimenting with vintage equipment and arcane printing processes, he was no longer trying to document the real world, as a traditional photographer would. Yes, he was using a camera, and these were certainly photographs. But the resulting images go deeper. They’re memories. They’re dreams. “Before that, I was making literal, specific photographs of vernacular culture and scenes,” he says. “After that, I began to look for subtle, mysterious moments, when the world was perfectly natural and vivid, and at the same time a little mysterious. In my mind, it gave the viewer much more credit for intelligence, to let them see what they wanted to.”

In recent years, photography has been a constant through a series of difficult transitions in Carter’s life. He photographed his mother as her mind succumbed to Alzheimer’s. About a decade ago, a form of melanoma blinded him in his non-dominant left eye. He responded with a series of “dirty pictures” doused in chemicals to represent his loss. “I was trying hard to destroy what I loved, what I thought was precious, in the hopes of bringing forth something new,” he says. And when Pat became ill from cancer, he made a progression of portraits that transfix the viewer with her intelligent, unwavering gaze. She died in 2014 at the age of 82.

As always, he kept making art, applying lessons he’d learned from reading Foote years earlier: “It made me understand how important it was to love other people, and how sometimes, things just fell apart and you couldn’t put them back together. But you kept going.”

Carter likes to visit the marshes on the south side of Beaumont. There’s a city wastewater plant nearby. When treated effluent is released from the plant, it passes through a succession of eight “cells,” known collectively as the Cattail Marsh Scenic Wetlands, each cleansing the water a little more. He rides his bicycle or walks the trails that circle the reclamation area. It doesn’t always smell pristine, but Carter has never felt comfortable with perfection. Perfection is boring.

He strolls onto a wooden boardwalk extending onto the marsh, past wood ducks and other waterfowl. An alligator noses across the surface toward an egret, pounces, and misses. Beyond the blue water, the land is flat, almost featureless. “Before we got whacked by these monster hurricanes in the last 15 or 20 years, everything was just deeply green and wooded,” Carter says. “We lost a third of the trees in Rita. For my taste, that worked fine.”

A poet of the ordinary seeks ordinary landscapes. The secret to finding the subtle and mysterious in the everyday world, Carter says, is to resist intelligence, to intuitively and instinctively feel the value in a small gesture, in the light, in the poetry all around us.

“Make the picture,” he says. “You’ve got the rest of your life to figure out what it means. Just make the picture.”

Keith Carter’s Beaumont

Lunch

Carter swears by the chicken salad at Katharine and Company, a lunch spot in an ornate former drugstore that anchors the historic, Spanish-style Mildred Building. Standout specials include the cornmeal-crusted redfish topped with crawfish etouffee.

1495 Calder Ave. 409-833-9919; katharineandcompany.com

See and Do

Beaumont preserves its history in museums such as at the opulent, 1906-era McFaddin-Ward House (below) and the Fire Museum of Texas, which boasts the world’s largest functioning fire hydrant (painted white with black spots to resemble the world’s largest Dalmatian). Along Hillebrandt Bayou just off Interstate 10, the Cattail Marsh Scenic Wetlands is 900 acres of wetlands, woodlands, levee trails, and bayou on the migratory flightpaths for a number of feathered species. “There’s lots of alligators and birds,” Carter says, not to mention a 520-foot boardwalk and an elevated education center that features a covered wraparound porch for bird viewing across the marsh.

Dinner

Laid-back Tia Juanita’s Fish Camp cleverly mixes up Cajun and Tex-Mex dishes, drawing big local crowds. The blackened crab nachos are a hit, as are the blackened scallops and jumbo shrimp heaped onto cheesy enchiladas. More of a traditionalist? Opt for po’boys, fried seafood baskets, or fish tacos.

5555 Calder Ave. 409-434-4532

Nightlife

The Logon Cafe has mostly outlived its days as an internet cafe and morphed into more of a “funky restaurant-bar-coffee shop,” Carter says, with live music and karaoke, a checkerboard dance floor, games, lots of art, and a sign out front touting mediocre service and good times—a promise it keeps.

3805 Calder Ave. 409-833-6950; logoncafe.net